Flirting With Fascism

The National Conservatism Conference in Washington had a very 1930s vibe.

FOR ANYONE with a basic grasp of history, a political conference called “National Conservatism” likely carries disturbing echoes of “National Socialism.” But the organizers of the “National Conservatism Conference,” which met in Washington, DC last week, take issue with that. “It’s not the 1930s,” said Christopher DeMuth, the former president of the American Enterprise Institute, in his opening remarks—DeMuth insisted that the better historical analogy would be the religious “Great Awakenings” in England and America in the 18th and 19th centuries. But with speaker after speaker assailing “cosmopolitan elites” and promoting racially exclusive economic populism, the whole event had a very 1930s vibe.

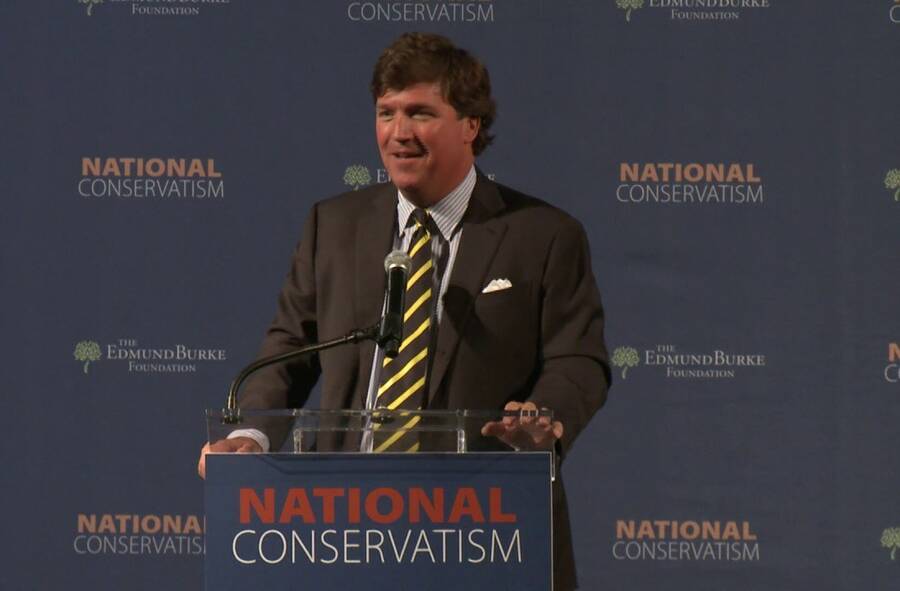

Tucker Carlson, whose Fox News show has become easily the most influential white nationalist media platform in the United States, gave a keynote address dripping with venom against the press, minorities, and the organized left, at one point openly expressing skepticism of democracy. University of Pennsylvania law professor Amy Wax, in a panel on immigration, mused that “our country will be better off with more whites and fewer nonwhites.” John Bolton, Donald Trump’s national security advisor, invoked the term “America First” during his remarks. “We all know the historical association ‘America First’ has for some people,” he said, before dismissing those concerns out of hand.

This is not the first time conservative nationalists in the US have been fascist-curious while simultaneously disavowing the openly Nazi right. The similarities between “national conservatism” and the America First Committee and its fellow-travelers in the pre-World War II era are unignorable. In November 1939, Rep. Martin Dies, chairman of the House Un-American Activities Committee, appeared at a “MASS MEETING FOR AMERICA” at Madison Square Garden, where he condemned Nazis and Communists as thoroughly un-American—even though one of the organizers of the meeting, Merwin Hart, was a staunch supporter of Francisco Franco and his fascist regime in Spain and a prominent supporter of immigration restrictions to prevent New York from being overwhelmed by Jewish refugees.

Like that earlier generation of right-wing activists, today’s national conservatives are obsessed with immigration. True, David Brog, one of the organizers of last week’s conference, insisted that national conservatives are not anti-immigrant. But this is a fig leaf. Wax explicitly made an argument for limiting the number of nonwhites entering the US. Carlson, in his keynote, doubled down on Trump’s recent attacks on Somali-American Rep. Ilhan Omar. “We rescued you from a refugee camp,” Carlson said. “Stop lecturing us.” (The next day, Trump supporters at a mass rally in North Carolina broke out into a chant of “send her back” when Trump mentioned Omar’s name.)

Even setting aside the obvious racism on display, the speakers at the conference failed to engage with any of the basic history of immigration and nativism in the US. Brog spoke movingly of his immigrant grandfather as a triumph of the assimilationist model—a Romanian Jew who emigrated to America, learned English, and became a good patriotic American—but failed to mention that the 1924 Immigration Act was designed specifically to exclude Eastern European Jews (among other undesirable European ethnic groups) from entering the country.

This maddening lack of historicity extended to the very idea of the “nation” itself. To hear multiple speakers tell it, nations are not ever-evolving and shifting social constructs, but rather organic and eternal constants in human history.

The political philosopher Michael Anton delivered a ponderous lecture to this effect. In his speech, Anton—best known as the author of the infamous “Flight 93 election” essay, which argued that Donald Trump’s campaign was a last-ditch effort to prevent globalist liberals from seizing permanent power in America—denounced the “soft imperialism” of globalization, which “makes people more interchangeable and fungible in the labor market.” But his main concern was with the internationalization of particular forms of political culture; he claimed “political correctness” is one of the great global crises today. Revealingly, he also conceded that borders—one of the foundational elements of nation-states—are arbitrary and porous, but added that “if we try to suppress that impulse we are going against nature.” Nations, to Anton and his enthusiastic audience, are scientific facts as natural as gravity.

R.R. Reno, the editor of First Things magazine, suggested that the separation of church and state in the US Constitution is a positive thing because it means that the state is not bound by the concept of universal Christian brotherhood. This means in practice that the state can define a national community and enforce its borders. But he had little to say about what that looks like in practice—from federal immigration exclusion in the 1920s, to the mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War II, to the entirety of the Jim Crow racial apartheid state, to the horrific detention centers on the US–Mexico border today.

To acknowledge any of this history would be to admit what only Wax seemed willing to say out loud: that it’s all about race. The attendees and speakers at the conference were, unsurprisingly, overwhelmingly white, yet they dismissed the idea that their articulated beliefs could be construed as racist. During Carlson’s keynote, he wedged sneers at his critics for crying “racist!” in between racist remarks about Omar, jeremiads against the media (“I know there’s a bunch of reporters here, so . . . screw you”), and an attack on Elizabeth Warren and her donors (“She’s a tragedy, because she’s now obsessed with racism, which is why the finance world supports her”)—all to gleeful applause.

But Carlson was subtle compared to Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley, who has sparked widespread condemnation for peppering his keynote address with derogatory references to a “cosmopolitan elite.” The term “cosmopolitan” was used throughout the 20th century to imply Jewish control over powerful global institutions. In the US, it has often been explicitly counterposed with American nationalism by prominent antisemites. “The battle is the American Soul against the Anti-American Spirit personified by the International Jew!” wrote self-proclaimed American nationalist Gerald L.K. Smith in 1948. “It is Nationalism versus Cosmopolitanism!”

Hawley, for his part, said that “our national solidarity has been broken by the globalizing and liberationist policies of the cosmopolitan agenda.” He also singled out academics for ire, saying that “the nation’s leading academics will gladly say [that they] distrust patriotism and dislike the common culture left to us by our forebearers.” As evidence, Hawley cited the work of four academics, three of whom—Leo Marx, Richard Sennett, and Martha Nussbaum—are Jewish.

Hawley’s remarks highlight the key paradox of “national conservatism.” Much of the agenda and rhetoric of “national conservatives” have antecedents in the self-proclaimed “nationalists” of the 1940s and 1950s, many of whom were explicitly antisemitic. But the explicit targets of American nationalism have changed. While “cosmopolitan” Jews—i.e., left-wing academics, writers, artists, and activists—are suspect, shifts in both American and Israeli politics over the past few generations have allowed a once stateless people to be incorporated into a Western ethnonationalist vision.

Whereas last century’s nationalists saw “international Judaism” as the greatest enemy of Christian civilization, 21st-century American nationalists have managed to ally with a minority of Jews—including Brog and Yoram Hazony, among the organizers—against the Muslim world. At the conference, “Judeo-Christian” civilization was frequently contrasted with Islam, which the far right increasingly sees as the main threat. Facing a backlash over the use of the term “cosmopolitan,” Hawley later defended himself against accusations of antisemitism on Twitter as “an ardent advocate of the state of Israel and the Jewish people.” But this conflation of the state of Israel and the Jewish people is the entire point. To today’s far right, Israel is a firm ally against Islam, while “cosmopolitans,” many of whom just happen to be Jewish, are suspect.

Hawley’s defenders, like Rich Lowry of the National Review, have insisted that the term “cosmopolitan” does not necessarily have antisemitic overtones. But both Hawley and Carlson made a point of singling out monopoly capital and its so-called cosmopolitan influences for censure—longstanding antisemitic tropes dating back to Henry Ford’s International Jew. This was a running theme throughout the conference: that the libertarian, pro-business faction in the Republican coalition has gone too far, and that perhaps the private sector today is a bigger threat to human freedom.

Lest anyone on the left think that Tucker and his friends are potential anti-capitalist allies, their specific objections to corporate capitalism are revealing. To them, the real issue is not labor exploitation, but rather the “corporate alliance with the progressive left.” In addition to Silicon Valley, which has long drawn the wrath of cultural conservatives, Carlson also singled out Nabisco’s recent LGBTQ-friendly Oreo packaging as an example of how corporate capitalism threatens conservative nationalists today.

Hawley, for his part, inveighed against “multinational corporations” as responsible for “flat wages . . . lost jobs . . . declining investment and declining opportunity” in middle America. Left unmentioned: Hawley opposed a minimum-wage increase on the campaign trail in 2018 and supported Missouri’s draconian right-to-work ballot initiative that would have stripped workers of their basic right to unionize—a proposal that Missourians voted down last year by an overwhelming margin.

The constant odes to the forgotten man trampled upon by coastal elites came to feel grotesque, considering that the conference was held in the ballroom of a Ritz-Carlton in downtown Washington, where room prices start at $300 a night. Perhaps no one better embodied this contradiction than J.D. Vance, the Yale Law graduate-turned-venture capitalist-turned-populist who wrote the bestselling 2016 memoir Hillbilly Elegy. Vance tore into “libertarianism as the animating force in the American conservative movement over the past generation,” castigating libertarians for refusing to use their political power to help “our people” in America.

Vance, unlike many conservatives, actually does talk about the material crises facing Americans today, ranging from income inequality to deindustrialization to the opioid epidemic. But his dissection of the ills afflicting “our people” had distinct racialist and nativist components. “Our people aren’t having enough children to replace themselves,” he said, citing birthrates as the key metric of a healthy society. It’s worth remembering that a generation ago, Ronald Reagan led the American right in condemning African American single mothers as drug-ridden, promiscuous “welfare queens.” When today’s conservatives talk about “our people” and birthrates, it’s not hard to imagine whose birthrates they’re really concerned about.

For all of the talk of “national conservatism” being a great rupture with the past, the arguments and rhetoric at the conference often felt like throwbacks. Mary Eberstadt, a former official in the Reagan administration and current fellow at the Faith & Reason Institute, made this explicit, calling for a revival of the culture wars of the 1990s. Like Vance, she argued that libertarianism is a dead end—it does not offer a solution, for example, to parents in middle America who don’t want their kids taught “sexual revolution curricula” but can’t afford to send their kids to private school. Eberstadt also warned darkly of the “flight from biological science” on the left, with the “invasion of biological males into traditionally female spaces.” Anti-trans rhetoric permeated the conference, and is clearly one of the most important tropes of the American right today. While Hazony went out of his way to condemn the white nationalist right for its racialist biological determinism, other speakers at the conference readily embraced biological determinism in the form of transphobia.

National conservatives fear and loathe the epithet “fascist,” but consistently refuse to face the actual foundations of that critique from the left. True, the national conservative conference was not a uniformed paramilitary affair (although the ubiquitous Brooks Brothers blazers and khaki chinos worn by most of the attendees are arguably a kind of uniform), and the speakers distanced themselves from the openly Nazi right, but the overtones were ominous. They talked about reviving American nationalism, castigated capitalism for failing to serve “our people,” insisted on the need to enforce boundaries and borders, and argued that the nation-state is a natural, inevitable form of human affinity.

At minimum, these are the same semiotics as a far-right tradition that stretches from Mussolini to Franco to John B. Trevor, the architect of the 1924 immigration act, and to Gerald L.K. Smith, the right-wing demagogue who was labeled America’s foremost antisemite in 1950s. All of these far-right figures, it’s worth remembering, called themselves nationalists.

David Austin Walsh is a PhD candidate in history at Princeton University. His dissertation is on the relationship between the far right and the American conservative movement in the mid-20th century. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Guardian, Dissent, and the Washington Monthly, among other publications.