Does Everybody Really Hate the Jews?

Unpacking the suspect framing of a new survey on campus antisemitism.

ON MONDAY, Bari Weiss—the former New York Times opinion editor who now publishes her own popular right-wing email newsletter—sent out an essay titled “Everybody Hates the Jews.” Like much of Weiss’s work, the piece centered on the specter of rising antisemitism in the United States. As a central piece of evidence, she cited a just-released poll of students who identify as “openly Jewish,” conducted by the nonprofit Louis D. Brandeis Center, in which nearly half of respondents said they had felt the need to hide their Jewish identity on campus due to concerns about being physically or verbally attacked, or socially or academically marginalized. Weiss used the study’s findings to support her essay’s argument that antisemitism is pervasive across the American political spectrum and symptomatic of a larger cultural abandonment of respect for individual difference. The Jewish press, including JTA and The Jerusalem Post, reported on the study without disputing its framing.

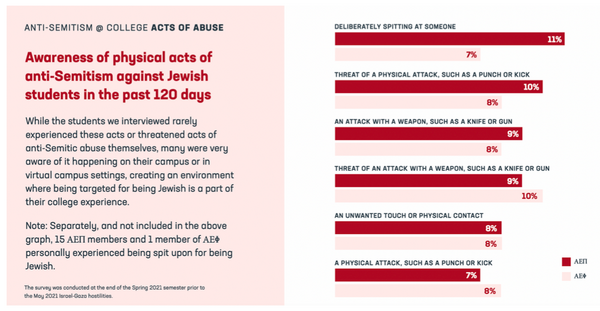

The study in question contains some alarming findings: Fourteen respondents reported having been attacked with a weapon—a small percentage of total students surveyed (2%) but still quite concerning at any level. About 56% of students reported being victims of a verbal antisemitic attack in the past 120 days at the time the study was conducted in April. (Weiss mis-cited the latter finding in her newsletter, writing that nearly 70% of students had personally experienced antisemitism, when in fact the 70% statistic included students who said they “were familiar with” an antisemitic incident.)

For this week’s newsletter (subscribe here!), I decided to take a close look at the study to see whether the reaction of Weiss and other commentators was warranted. A few observations immediately stood out to me. First of all, the poll was conducted by Cohen Research Group for the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law, a group that is not to be confused with the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University (I saw a couple of tweets conflating the two). The Brandeis Center is a nonprofit that often brings harassment claims on behalf of Zionist students who say they are victimized by campus politics. Its cofounder, Kenneth Marcus, served as Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights in the Department of Education in the Trump administration and made a name for himself attempting to more strictly codify what he considered antisemitism—including many forms of Palestinian activism—as a federal civil rights violation. (Michael Cohen, the CEO of the Cohen Research Group, insisted in a phone conversation that the findings were not influenced by the Brandeis Center’s agenda: “There was never a moment where they said to me, ‘Can you look at the data this way, so it looks like this?’’’ he said.)

Second of all, the study drew not from a representative sample of Jewish college students, but from students who are members of the Jewish fraternity Alpha Epsilon Pi (AEPi) or the Jewish sorority Alpha Epsilon Phi (AEPhi); all active members around the country received an invitation to participate in the survey by email, and the survey’s results are based on responses from 710 AEPi and 317 AEPhi members across a wide variety of colleges. On the one hand, since the poll is specifically looking at the experiences of “college students who claim a strong sense of Jewish identity,” targeting members of Jewish Greek life is an effective strategy; more than three in five respondents said they also belonged to campus Hillel and nearly half said they belonged to Chabad. “We wanted people who are super engaged with being Jewish,” Cohen said. But these Greek organizations tend to attract students with a particular set of political affiliations, who often strongly identify as Zionists: In this particular poll, 84% of AEPi and 85% of AEPhi respondents described themselves as “supportive of Israel.”

These distinctions matter because the survey—like other antisemitism reports I’ve written about—conflates both straightforward antisemitic comments (jokes that Jews are “greedy” or “cheap” or “untrustworthy”) with anti-Zionist speech. A Jewish student who is “supportive of Israel” is likely to consider the statement “Zionism is a form of white supremacy” to be antisemitism; other Jewish students might disagree. This study lists all of the aforementioned types of comments—alongside other offenses, like uses of the term “Jewish American Princess”—as examples of verbal antisemitism.

For help analyzing the study, I called Matt Boxer, an assistant research professor at Brandeis University with expertise in sociodemographic research on US Jewish communities. Boxer expressed concerns about the sample. “This was a select group of students. If I surveyed my closest friends, and tried to extrapolate from their responses to the entire American Jewish community, that would be a similar level of egregiousness to trying to extrapolate from a few hundred AEPi or AEPhi members to Jewish college students all across America,” he said. “In defense of the folks who did this research, they explicitly don’t say that they’re extrapolating to all college students. But of course, that’s going to be the implication that people take from this.”

I also found the study hard to parse, because many of the results described not just acts of antisemitism students had personally experienced but acts they were “aware of,” which could include events they had experienced, witnessed, or simply heard about. While the occurrence of antisemitic incidents is troubling regardless of frequency, and students’ awareness of any such episodes certainly impacts a school’s climate, lumping personal experience and word of mouth into a single statistic makes it difficult to judge how many incidents actually occurred. (You can see the exact breakdown of what students experienced vs. heard vs. observed in the detailed crosstabs that Cohen sent me when I reached out about the study.)

Overall, Boxer said, while any reports of antisemitic verbal and physical attacks constitute a problem, the study’s results were not particularly alarming or surprising to him. “What’s being reported in this survey is mostly a matter of microaggression. They mostly don’t rise to the level of assault,” he said, referring to the types of antisemitic incidents cited in detail in the study’s results. “It’s not that any of this is okay. It’s not.” But in his own experience surveying representative samples of Jewish students on various college campuses in the United States, he’s generally found that most students “don’t tell us that they feel threatened.” Compare this measured assessment to that of Kenneth Marcus, who said his organization’s study’s findings paint a picture of a climate “more closely resembling previous dark periods in our history.”

I eagerly await the day one of the studies Boxer describes gets a breathless writeup in Weiss’s Substack. In the meantime, it’s hard not to wonder whether the frequent fear-mongering in mainstream Jewish discourse about campus experiences could actually itself contribute to making Jewish students feel less safe. Cynically, many Israel-advocacy organizations have a reason to keep pushing this narrative, since it helps stoke fear about Palestinian solidarity activism on campus. But they aren’t helping students to develop a Jewish identity that’s not just defined by fear, isolation, and threat.

A previous version of this piece misrepresented the JTA article about the Brandeis Center’s study.

Mari Cohen is associate editor at Jewish Currents.