Degrees of Separation

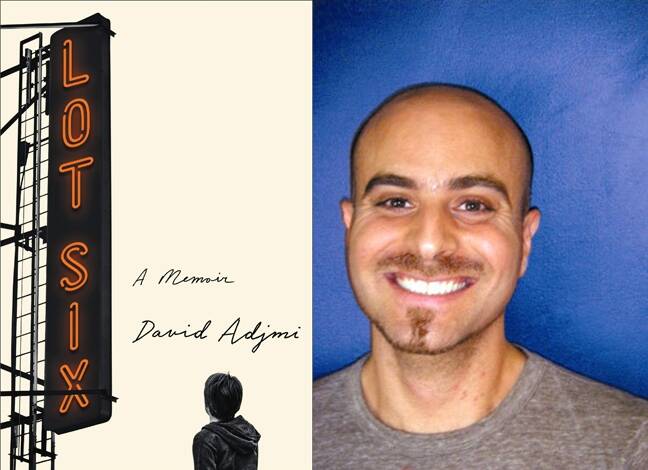

Playwright David Adjmi discusses his estrangement from the Syrian Jewish community, his ambivalence about identity politics, and his new memoir Lot Six.

When the playwright David Adjmi came up with the title Lot Six for his memoir, he thought it was “so punk rock”—but maybe only to him. The term comes from the Syrian Jewish business community where it’s a pricing code for “three dollars”—and also derogatory slang for “queer” (like the proverbial three-dollar bill). He was amazed, he told me, when his gesture was applauded by some fellow queer Syrian Jews in the chat portion of an online reading. “I never imagined I could have a homecoming,” said Adjmi, who is now 47, “and there’s something really sweet about it, even if it’s for like six people.”

Adjmi’s astonished delight makes sense given the lonely upbringing he chronicles in the book, which came out this summer. Like many a Künstlerroman, it’s a story of breaking away from a stifling, rule-bound religiosity that couldn’t assimilate the questions, creativity, and queerness of a restive boy. What distinguishes Lot Six, besides its piercing self-scrutiny and downright hilarity, is that—like the fashion designer Isaac Mizrachi’s less compelling I.M.: A Memoir, which was published last year—it takes place in the closed, seldom-discussed Syrian Jewish community of Midwood, Brooklyn.

Raised by an often aloof mother who dropped out of high school at 16 to marry a domineering and eventually absent businessman, Adjmi bristled early at the dogma of the Yeshivah of Flatbush, where his father sent him in a sudden pang of desire to refasten the family’s attenuated ties to Judaism. He dropped out of the yeshiva and enrolled in a private high school in Manhattan, where he snagged a job as a salesperson at a high-end retail shop by pretending to be French, affecting an accent for hours at a time.

As a rebellious, philosophically adventurous college student, Adjmi discovered his calling when he saw John Guare’s Six Degrees of Separation, in which a charming gay Black man cons wealthy white people by posing as the son of Sidney Poitier. “The imagination,” Guare’s character declares, “is the passport we create to take us into the real world.” Astounded, Adjmi felt the playwright “knew me”; to him, Six Degrees showed how theater could perfectly address the questions of self-making, representation, and belonging that both plagued and animated him.

The book ends in 2009 with the complicated success of Adjmi’s first major play, Stunning, presented by Lincoln Center Theater. A barbed and tragic yet side-splitting satire of the parochialism, consumerism, and racism of the Syrian Jewish community, it won him giddy attention in the theater world and galled notoriety back in Midwood.

It also led to Lot Six. A HarperCollins editor who’d seen the play reached out to Adjmi and they agreed he’d write ten essays about the art that inspired him. But hundreds of manuscript pages about the likes of Jean-Paul Gaultier and Alfred Hitchcock couldn’t cohere, and editors prodded him to probe his own life. “What did they want from me? I couldn’t understand it,” Adjmi recalled. “I thought, ‘I have to beef this up in some way to give them a juicy story,’ and I didn’t think there was one.” It took nearly a decade, but he figured it out.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Alisa Solomon: You haven’t written about the Syrian Jewish community since Stunning. You took some flak back then from people who resented what they thought was an unfavorable portrayal of the community. How did that affect your writing Lot Six?

David Adjmi: I have no relationship to this community anymore. I really did just pluck myself out, so I don’t care what they think. And I don’t feel like Lot Six is a terrible denunciation of the community. About a week ago, I did a Zoom reading for a Sephardic Syrian Jewish group in DC. In the Q&A, a bunch of them said, “I’m so proud of you.” I could feel myself getting strangely emotional. I realized that no one from that community had ever said anything like that to me. The community is very reactionary, but now there are groups of progressive Syrian Jewish people, even a queer group!

AS: How did you develop your progressive politics in the absence of visible models?

DA: I think it was innate. My parents were Republican and apolitical. There was a low hum of right-wing ideology that suffused everything in my childhood, but it never resonated with me. I always felt it was one of the things that kept me at a remove from my family. It’s strange because children don’t really have ideologies, but I sort of did. In my yeshiva, my introduction to race was that Noah’s son saw him naked when he was drunk and the punishment was, “You’re going to have a black kid.” I remember vividly thinking, “That’s not right.” Or the horrible prayer I had to say every morning: “Thank You for not making me a woman.” I was not into Zionism from day one. There was a class on Zionism at the yeshiva and you had to take it. I got out of it, I don’t remember how.

AS: It’s striking in Lot Six that your coming out to your family is merely—literally—a footnote.

DA: I added the footnote like three days before publication because people were asking me. But it was a non-event. I didn’t have a relationship of intimacy with anyone in my family; there wasn’t even a false exterior that I was going to puncture with this information. I write in the book about how we never had important conversations, never talked about anything.

AS: And yet when you were an adolescent, they sensed you were suffering and sent you to a shrink, who—it turned out—sensed you were gay and wanted to “cure” you. It’s wonderfully complicated, because this therapist also showed you a world beyond your insular community—a world of books, ideas, foreign films . . .

DA: At the time I thought it was the greatest thing: “You can cure me? Fantastic!” Also, he never told me what to do to be “cured.” Thank God, right? I was so angry with him once I finally came out, and I also really loved him. In some ways I still love that therapist. He opened the world to me. I wanted to capture that in the present tense in the book, to keep that feeling of aching and strange cognitive dissonance.

AS: To some degree, your mother opened the world to you, too. Lot Six opens with a recounting of her taking you to see Sweeney Todd when you were eight years old. It’s your artistic origin story.

DA: The show came as a disruption and a shock to me. It’s like modernist novels, where reality always comes as a shock. Or in my favorite memoir, Richard Wright’s Black Boy, when he’s a little boy and goes to the bar: a young child interfacing with an adult world and seeing and experiencing something you’re not really supposed to see and experience. There’s some kind of crazy artistic curiosity that awakens: the feeling of this young child being assaulted by something that’s strangely wonderful or confusing or pleasant. That was absolutely Sweeney Todd for me. I was violently ill after I saw it, but I still loved it.

AS: Drama is a dialectical form. Characters argue and often contradict each other and/or themselves. In a memoir there’s a singularity of voice and an interiority that drama doesn’t allow. What was it like to shift into this other form?

DA: I really get off on the dialectical aspect of plays. I can’t figure out how to have a single point of view because I always want to have the opposite point of view also. That quality is the essence of a playwright. And when I did my first drafts of this book, I was not a character. I thought it would be vulgar, almost, to write about my own feelings and experiences—like, who cares? And everyone kept saying to me, “No, no, no, you have to make yourself the character.” Learning how to develop the act of ventriloquism, of throwing your voice as yourself, and also making yourself both subject and object simultaneously, was arduous. I had to really teach myself from the ground up.

AS: Your prose is filled with inventive metaphors and similes, sometimes several in a row that swell like waves. That’s so different from playwriting. It seems like writing the memoir allowed for a new engagement with that kind of figurative prose.

DA: Absolutely. I felt the need to get very granular. I didn’t have a story where I’m a war veteran or my father chewed off his own leg. I had to turn to the Proustian model of chronicling consciousness—my favorite thing. And it’s a very gay thing: Marcel Proust, Henry James, Edmund White. I wanted people to know how things felt in the most detailed way. Maybe I tipped into compulsivity with it, trying to get as specific as possible, impasto-ing, laying it on. Minute textures are meaningful in a way that transcends language.

I learned a lot about myself being forced to articulate the problems of having a self and how that led to me becoming a playwright who diffracts himself into the plays, where I don’t have to have a single unified self.

AS: What did you learn?

DA: It wasn’t until I wrote the book that I realized how much I triumphed in a certain way. And that was shocking, ’cause I’m sort of a negative, sad-sack Jew. But I actually thought, “No, there’s something miraculous about this story.” Memoir has a moral axis to it, and I don’t like that axis. I resist it because I’m a diffracted, dialectical, contradictory person. But if I’m honest with myself, without being treacly or cloying about it, there was something redemptive in this trajectory that I’m outlining. I was very surprised by that. I thought my book was going to be like [Hanya Yanagihara’s] A Little Life. You know: it’s been a disaster from the get-go. It didn’t actually turn out like that.

AS: But I imagine you self-consciously wanted to avoid the abjection-to-triumph trope.

DA: Yes. But resisting the cliché, you can end up repressing something truthful. And I didn’t want to be nihilistic. So, I thought, I’m going reach for something at the end without pushing anything. It’s not an ending that feels redemptive, but it’s not an ending that makes you feel really crappy.

AS: One of the appeals of playwriting, you said, is to refract yourself into various characters and not be pinned down in any way. In the past you’ve said you resist identity politics. Has that changed for you after writing the memoir or amid the emergence of progressive organizing among Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews and Jews of color?

DA: I grew up with no context for how to think about my identity. I was like, “Oh, I guess I'm white.” But I knew that wasn’t right, though I’m very light skinned, so I have light skin privilege. But I’m an Arab. No one filled in my heritage. It was like a shadow, like an outline of something. Last year I was at Sundance and there were many Arab artists there. They were speaking Arabic and I suddenly felt this strange pang of longing to speak Arabic with them. I thought, “Maybe I can write about this one day,” about feeling estranged from what’s native, being inculcated with your own heritage in such a way that it was distorted inside of you and then wanting to un-distort it.

I understand the importance and urgency of identity politics and what it means for this historical moment. I’m happy to call myself a gay man or queer. And I’m happy to call myself a Syrian Sephardic Jew, even though it’s so clunky. But for me personally, it’s complicated. I think sometimes identity politics interfaces with social media and capitalism in a reductive way and you have a sort of placard for your identity. I’m resistant to tribal identifications in general. I’m really a loner. When Syrian Jews want to hang out with me, I enjoy it, but it’s not my default and it doesn’t give me a sense of solace. I really feel a kind of catholicity with all people and at the same time a very old-school existentialist remove.

AS: Does being Jewish mean anything to you now?

DA: I didn’t think it did until I was in my thirties. Until then I thought of Jewishness as something that had traumatized me. I hadn’t understood how the right-wing politics and right-wing Zionism could be separate from other parts of Jewishness. There’s a sensibility that I absorbed and feel very fluent with that you could loosely describe as Jewish. And it feels native to me, even though I rejected it vehemently when I left the yeshiva. The process of remediating that was meeting people when I was older who were Jewish and observant and progressive. I started to realize, “Oh, this could be multifaceted.”

Alisa Solomon is the author of Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof, and of Re-Dressing the Canon: Essays on Theater and Gender and a professor at the Columbia School of Journalism.