As we were filling a suitcase with mandarins and baklava, arguing over how many toys I could bring, the Soviet army invaded. Everyone ran out to look, were they shooting a movie? No. They were shooting around the Caspian Sea. Papa wouldn’t let me sleep facing the window because of “mischievous bullets.” I didn’t understand. When he picked us up in the morning, Uncle Seryozha said to wear two pairs of pants on the ride to the airport because we would piss ourselves.

I must have had my eyes closed all the way from Baku to Moscow. I don’t remember the bodies dangling over the balcony railings or puddles of blood. I don’t even remember my father suddenly leaving us at the airport because the phone lines were cut and he still didn’t know how Marina and Tetya Betya were. He tried to walk all the way to Tbilisky Prospect but was surrounded by soldiers. Things were about to take a turn for the worse when a watchman ran out and told them that Papa lived in his building and let him stay in his booth for the night.

Anyway, none of that happened to me. All I remember is falling asleep to the silhouette of a tank against our lace curtains, then lo and behold: these miraculous doors, self-opening onto the dazzling fluorescence of paradise. Out of the darkness, in Mama’s arms, I was borne into the whitest place I had ever seen, like God’s own CVS. The faceless, unbodied American consul asked what would happen if they didn’t let us come. Babulya: “We’ll all be killed.” Hahaha. But it worked. We were dubbed refugees.

To celebrate, we got in line in front of McDonald’s. It was only four hours long, and Papa had already been standing for two. Our hero, he’d been the one who’d applied for our refugee interview while he was smuggling Armenian friends out of Baku, after seeing his friend’s auntie’s neck with a screwdriver sticking out of it. He applied for me, him, and Mama. Babulya, who ended up an Israeli, never forgave him.

My parents flew back to Baku to sell almost all our possessions, leaving me in my grandparents’ match factory town, Balabanovo. They made me swear not to tell anyone because the neighbors would get very mad; only Jews were allowed to leave, and we were Jews, and they hated Jews. The kids and I hung out under the stairs showing each other our assholes instead.

One day, Babulya walked in on me on my knees, furiously crossing myself. She told me to stop.

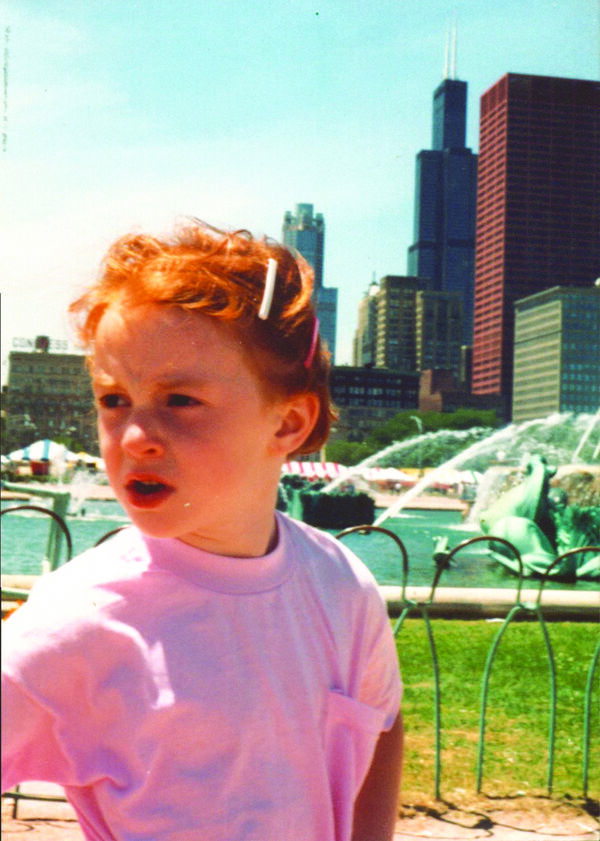

People will always ask, disbelieving, “You really remember?” As if my past is something outside me they know about now that I couldn’t have. Like I had lived the most vivid and formative part of my life flatlined in terms of consciousness. What could a child have possibly seen? Well, compare the piss-reek of Soviet streets and suburban lawns viewed from behind tinted minivan windows; Fruit Roll-Ups and gritty pastila, wrapped up in cones of Pravda, haggled down from the tannic hands of gold-toothed villagers. My consciousness was probably formed from these very comparisons. It’s not my fault that Azerbaijan sounds like an Orientalist hallucination and Soviet Russia, the oldest joke in the book. My childhood photos are Kodachrome paisley, black-and-white gray, as if I’d been born and died in the ’60s then reincarnated neon at a Chuck E. Cheese.

I was always a god, seeing the full truth of things as they were, instantaneously collapsed in the past, present, and future. I want to say “with my little eyes,” but then I remember that eyes stay the same size for your whole life.

Two silent men from the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, HIAS, picked us up at O’Hare and dropped us off at the Stars Motel in the city. Mama’s cold, leonine eyes floating over the dashboard, wandering between the sodium lights and red clouds. The bed in the first room was broken, and in the second, the first thing we saw on TV was a woman grasping a metal bar squatting over a man’s open mouth.

“Why is she doing that, Mama?”

“She has applesauce on her pipiska so he is eating it off.”

She was one month shy of 26. I was five-almost-six. Papa was 28.

Our first morning out, we marched straight to the nearest McDonald’s. Papa took pictures of me in the ball pit. It kept getting better. Back in the Stars Motel parking lot, there was a squashed M&M on the ground. “Mama, the streets are paved in candy!!!” We had been promised this exact pile of shit and received it ecstatically.

I don’t want to tell you about how pathetic our Soviet candy had been, but I am scared that you can’t surmise on your own how when this one kid got a piece of gum, which none of us had ever heard of before, it had somehow come down from Moscow, all of us took turns chewing it. Kids would collect and trade candy wrappers, they were new and colorful, plus they still smelled like candy. One time these kids said, go up to the second floor, there’s a pile of candy for you, and so I went and unwrapped them and every last one was a rock. Fuckers. Look at me now. I bet they’d choke on a rock for one bite of my M&M.

When Babulya was my age, she’d eaten the paint off the walls and salt off the floor because there was nothing else.

We had been promised

this exact pile of shit and

received it ecstatically.

The Jewish United Fund, that same JUF from the cans rattling through temple, placed us in their Family-to-Family Program. Jean and Jay would take us in for two weeks, help us with “aklimatizatsia,” then they would love us forever, we thought, just as we would love them. They lived in Olympia Fields, in a prairie-style ranch house made of stacked slate. Nothing like the plantation manor I’d been imagining from watching Isaura the Slave Girl.

As we were carrying our stuff in, Jean offered me a banana. I was still holding my beloved stuffed chimpanzee from the GDR.

“Monkey! Banana!” I couldn’t believe that I already had all the words I needed to clearly express myself.

“Do YOU want a banana?”

Jean said this loudly and slowly.

Fuck no. I SAID MONKEY BANANA.

I wanted to feed my monkey. We had been gorging ourselves on bananas all week.

I can see why children appear to be squealing, unconscious animal-things, how it was hard to see the all-seeing god in me when I was squawking shrill gibberish, going moo-moo and meow-meow, but with my god-eye, I’ll tell you that even then, even I knew that they thought of my parents as little animals, too.

But they were good, they were fine. That’s why I barely remember anything but their possessions and their anxieties, probably filtered through my parents’ own culture shock. Their desperate smiles. The white marble floor of Jean and Jay’s living room dipped, turning into an indoor koi pond. That’s the first thing I see from Olympia Fields: my father, out of sheer gratitude, scrubbing their koi pond.

Papa was shaken; Mama was energized, already leaping for the gold ring. She was gregarious with her superior English while he stayed silent, sulking and jealous. He purposely studied the words for confessing how her social success made him “feeling unmanly.” Jay could not fathom what in the hell Papa was trying to tell him.

One night, Jean and Jay drove us to Rogers Park, “the old Jewish neighborhood,” where we should have been living among all of Chicago’s other Soviet immigrants. This was the JUF’s fault. They’d stranded us and five other families in the south suburbs for their own reasons. Our destination was some Jewish restaurant with Jean and Jay’s friends, the kind of place people go to play up their supposed connection to, yes, what we had just fled. On the way to the restaurant, somebody handed me my first Barbie. I couldn’t believe my own disappointment. I was so used to asking and asking for things and Mama offering me bupkis “with butter,” “or how about cheese,” I’d been committed to waiting forever.

“We’ve only been here two weeks and I’ve already gotten my Barbie,” I whined. “Let’s go home.”

During this dinner, one of the rich Jews asked Papa what his favorite food was. What could he have said? Lyulya kebab with homemade narsharab? Namik’s mom’s baklava? Feijoa and sugar? He told him—proudly, like “I’m one of you now”— McDonald’s. The face the man made. “Very good, Vaud-dim. That’s very good.” Afterwards, Papa would always grimace out “very good” when he was mocking Americans.

The sociological literature alleges that “the American Jews” were disappointed in the 300,000 of us who came in the early ’90s because we weren’t religious enough—“secular,” and worse, “culturally Russian.” Even before we got here, they’d been upset that although we were supposed to be “fleeing religious oppression” so we could “practice Judaism,” most of us wanted to live in America rather than Israel. Awkward!

“We’ve only been here two weeks and I’ve already gotten my Barbie,” I whined. “Let’s go home.”

I don’t think that’s why we didn’t take to each other. Religion isn’t what binds the “American Jews” I’ve seen, it’s class. Whether that be the urban lefties looking down on our joyous embrace of prosperity or these suburban varietals who were just trying to look good “helping the poor.” We are supposed to be, like, your ancestors, dummies. Of course we are vulgar, materialistic, “arriviste and shtetl-chauvninists” from Eastern Europe (term borrowed from Norman Finkelstein!). Of course we make no sense, no duh we embarrass you. What’s wrong with us is the same thing that’s wrong with anybody: We’re trash. So what?

Only the Soviet Jews who adopted conservative values while they attained the requisite financial standing ended up integrating into the relevant American Jewries. My parents, despite having worked here for 30 years now and speaking idiomatic, if still poetical, English, hardly have any American friends, none of them Jewish.

The only thing that I fault Jean and Jay with is how, at a surely culturally-appropriate juncture, they stopped returning my parents’ phone calls. I know, there’s a statute of limitations on how long you have to keep up with pets of our ilk. But it was like we’re not family.

They moved us into a basement apartment in Matteson with their enormous white sectional, all their old bed sheets, which I still have (my grandparents, I am ashamed to admit, slept on Jean and Jay’s mattress for the next 20 years, or, oh my god, 25), and garbage bags full of hand-me-down clothes. They had more garbage than we had ever owned clothes.

Matteson was no Olympia Fields. Mama and Papa and I slept in the same room again. I only pretended to sleep, I was up listening to their pillow talk. Mama in her blue paisley housecoat with the bell sleeves, her cloak of miserable beauty. Papa telling Mama this was his favorite part of the day. She’d already gotten a job at a dialysis clinic, work started at 7, so they had to leave at 5:30. Papa walked her.

My first morning alone like this, I woke up and panicked and ran out into the dark. Everyone’s lights were still off, except for my upstairs neighbor’s. I could see her behind her blinds, in a rocking chair. I swear to God, she was cradling a macaque. I knocked on her door, imploring her to take care of me, too. “SOMEBODY NEEDS TO WATCH HER,” she told my father later that morning, loudly and slowly, after he had come home to an empty apartment. We got an old TV and a kitten.

In Baku, Mama compulsively brought home stray kittens and I would name them all Kisya, “kitty,” and then they would die. We decided the new, store-bought cat should have a new name. Koozja was an extremely beautiful long-haired calico with a half-black, half-orange face. I have always associated her sexiness with my mother’s. Her food smelled so good to me, I would eat it out of her bowl. Perfect Strangers came on at 6, right after Cheers. Balki had also come from an unpronounceable island where they fucked goats or whatever, and moved to where else but Chicago, to live with his uptight, thin-lipped Cousin Larry. “Don’t be reedeekoolos, Lerry!” Oh Balki, my brother, I was so happy when you reappeared several years later to sell me Boboli pizza crusts.

This is why my parents don’t take my memories seriously. These are the kinds of passions that made up my life, while they were out there scrambling up a sheer cliff. Like many other Soviet immigrants, Mama and Papa refused every form of aid offered to us almost immediately. We didn’t live off the dole, we were Americans now.

This is why my parents don’t take my memories seriously. These are the kinds of passions that made up my life, while they were out there scrambling up a sheer cliff.

“Do you think in English, Mama?”

“Sometimes.”

“I can’t imagine that I ever will.”

I went to JCC camp. One day, they asked us, as I understood it, to draw the most beautiful things we had ever seen in our lives on two paper plates, which they would then fill with dry beans and staple together. I drew the tricolor swirl of just-squeezed Aquafresh toothpaste on both. I couldn’t get over it. The counselors snickering at me “worshipping the Sprite can.” I recall this term as if it’s a trope, when really, it comes from a story told by a preppy girl from my high school who had a grand mal nervous breakdown after a “social service” trip to the global South, so shook was she by the poverty. The scene: The “explorer” comes to the spiritually bludgeoned Indigenous people to find that, in their mean little hut, among their handful of possessions, there is a crushed, rusted Sprite and they are praying to it. “The horror!” As if you don’t worship the Sprite can yourself—with amazing results!

Toward September, the grape leaves that grew on the parking lot fence behind our apartment were ready for harvesting. We pickled them and made dolma for Jean and Jay. They probably wouldn’t have liked to know that their dinner was grown behind the dumpster. Today, they call this kind of thing “wild-crafting.”

Instead of letting our strip mall shtetl send their kids to public school, we were bestowed with the gift of two years’ tuition at HANI, the Hebrew Academy of Northwest Indiana. None of the rich Jews we knew sent their kids there. It was across the state line; getting to school took two hours.

HANI was K-8, with 100 students. It was housed in a former TV station with two giant satellite dishes out back instead of a playground. Every day we had Hebrew class with a butch Israeli named Ms. Hanukah, harsh and authoritarian, which I found comforting. In Soviet preschool, our teachers had spanked us when we couldn’t fall asleep during nap time, we would get yelled at for i.e. not having the motor skills to embroider the Kremlin. They were getting us ready for real school, which was going to be a lot stricter. Here, other than in Ms. Hanukah’s class, all we did was eat animal crackers and roll around on the floor.

Why weren’t we being disparaged and disciplined? When would I get my chance to show off my patriotism? I would cut little strips off my clothes, chunks out of my hair, draw all over my arms and legs, and run out of class sobbing for no articulable reason. Nobody stopped me.

Some time in October, our first-grade teacher Mrs. Seaver showed us a made-for-TV movie called Molly’s Pilgrim. In the opening scene, eight-year-old Masha, inexplicably “Molly,” a Soviet Jewish immigrant, lingers, watching a group of American girls playing jump rope. The most popular one catches her peeking. “What are you looking at, BIG NOSE?” Their teacher distributes wooden clothespins, from which the children are asked to create little pilgrims. Like, for Thanksgiving. Idiot Masha/Molly dresses hers up as Russian peasants, which is mostly her idiot mama’s fault, who tells her that “vee ar pilgreemz in zis kantry, vee also kame khere too bee free.” So the clothespin serfs are actually supposed to be them, Masha and Mama: real-life, modern-day pilgrims. The children at school find this reasoning dumb as hell. But then the teacher, who also initially thinks that Masha is dumb as hell, suddenly realizes something: “No, children, Molly is right. She is a pilgrim!”

Mrs. Seaver said we should put on a play of Molly’s Pilgrim. We were constantly putting on plays and pageants. Melissa, the richest, most popular girl in our class wanted to star as Masha/Molly. Fine. I would take the supporting role. “What are you looking at, BIG NOSE?” I taunted Melissa. Were we being experimented on?

What American Jews didn’t understand is that for Soviet Jews, the everyday coping mechanism for dealing with pervasive but random institutional and interpersonal antisemitism was normalization. It was assimilated as an emotional strategy: not drawing attention to their experiences of oppression or discrimination, but diminishing them as much as they could; never inflating them into “trauma,” much less redemptive story arcs.

It was a point of pride to remain unshaken, perhaps the last glimmer of some kind of faith in the equality promised by communism. My parents, who came of age during perestroika, were idealistic internationalists. They didn’t want to be Jewish or Soviet or Russian or Azerbaijani; they didn’t put stock into anything that would have tied them to any identity, narrative, or other constraint on their thinking or place in the world. For them, being “Jewish” was only a ticket to freedom—they wanted all the way out of this story!

“What story?” my father will say. “There wasn’t a story. This is all bullshit. We never thought about any of this. We were just living.” And shake his head in disgust at my childish, American need to come to some gratifying conclusion.

I didn’t make this stuff up, though. These misunderstandings had an important purpose. The sociologists point out that, “The narrative of antisemitism that depicted the immigrants’ past in terms of suffering and humiliation . . . entrusted the host society with the role of liberator [toward whom] the immigrant was expected to be grateful and compliant” (Rapaport, Lomsky-Feder, Heider 2002).

One Halloween, recently, Mama dressed up like a peasant, just like the clothespins. She’d gotten the costume on Amazon. “Mama, what are you?” I asked her. “Ukrainian antisemite.”

“What story?” my father will say. “There wasn’t a story. This is all bullshit. We never thought about any of this. We were just living.” And shake his head in disgust at my childish, American need to come to some gratifying conclusion.

But: I’m not like my parents. I am a white middle-class millennial, I know the value of “trauma.” Luckily, my liberators had more gifts for me. Somebody told my father about the children’s theater in the basement of the Park Forest Public Library, across the street from the Sears. The woman who ran it was like a smaller and nicer Ms. Hanukah. She saw me, at six years old, having just barely learned to speak and read English, and she had a vision: I’d make the perfect Anne Frank.

Boy, was she right. As soon as I learned about Nazis, that they were murderers who liked to kill little Jewish girls and their families, I felt like I already knew her. Anne would have never gone to some weird-ass Jewish school if the Nazis hadn’t made her. Her family was “too Dutch,” “not religious enough,” “secular.” She didn’t really know she was Jewish, either, until somebody explained that it was what made her fit to be killed. I wanted to be her, to be the star, to earn the glamour of murder.

Anne would have wanted that, too. She was a ham. She also wanted to be an actress. It’s funny because Babulya is the same age, but I was never tempted to pretend to starve or get evacuated to Chelyabinsk. Her war and the war of this play—fashishty and Nazis, who it took me many years to figure out were the same thing—they happened in two different worlds. Anne’s was so much more important and real: We were the stars of this war, it took place in America!

Who among us doesn’t get off on imagining people just like them get murdered? What’s so special about my ensuing obsession with vicarious annihilation? Maybe just that it had been prefigured by my Soviet childhood fantasies of i.e. being swallowed up by a whale, shredded to little pieces through its baleen, and then penetrated by the same little metal bars that they probed us with at preschool? If that really happened?

I got the book to prepare for my role and read it under the desk in Ms. Hanukah’s class. I must have wanted to get caught. Maybe I was even hoping for some Nazi/Soviet preschool-style corporal punishment. Ms. Hanukah gruffly took my book away and after class, she sat me down with Mrs. Seaver. They said that what I had done wasn’t right and I musn’t do it again. However, they were extremely pleased that I was so serious about studying the Shoah.

“Of course I love the Shoah!!!!”

And with that, to my parents’ disgust and dismay, I became an American Jew.

After the Holocaust stuff, I didn’t have any trouble tearfully begging God for my life. I was spiritually trephinated, or at least they widened the hole. When Babulya had walked in on me on my knees in Balabanovo, she said, “We don’t do that,” but couldn’t say what we did instead. All she had known about being Jewish was hiding. My teachers lifted me up to the light of sublime annihilation—showed me the possibilities of imaginative masochism—delivered me into true religion out of the ultimate contradiction of being inundated with a vision of doom in paradise (Northwest Indiana).

Papa once found me like this, my face like a bloated carcass, tears flowing out of the slits of my oozing, practically swollen-shut eyes. I’d gotten poison ivy from catching frogs in the woods behind our apartment complex, we’d never heard of it, and was being treated with sugar pills and spoonfuls of watered-down vodka. Mama was worried that steroids would make me fat.

“What are you doing?”

I was out on the balcony, singing the sh’ma, our holiest prayer, to the stars, pleading with God.

“God?! A year ago, you were worshipping Dedushka Lenin! And Dedushka Stalin!! Remember?! There is no God!!!”

Hahahahahahaha.

Thank you HIAS.

Thank you JUF.

Thank you America.

Thank you God.

Bela Shayevich is a visual artist, writer, and translator best known for translating Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time. Her latest book is a translation of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We. She is currently a student in the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa.