Jewish Essay

An exploration of Jewishness in contemporary Russia.

I used to imagine Russia as a pile of rubble amidst a windswept wasteland. This vision is drawn from my hometown of Serpukhov, a small city 60 miles south of Moscow, where the foundation of the ruined belfry of the Raspyatsky Monastery sits, drowned by the snows in winter and swarmed by weeds in summer. Torn tarp billows from the belfry; apparently, at some point it was supposed to be restored, yet here it is, half-destroyed, exactly the same today, in my fortieth year, as when I was a child.

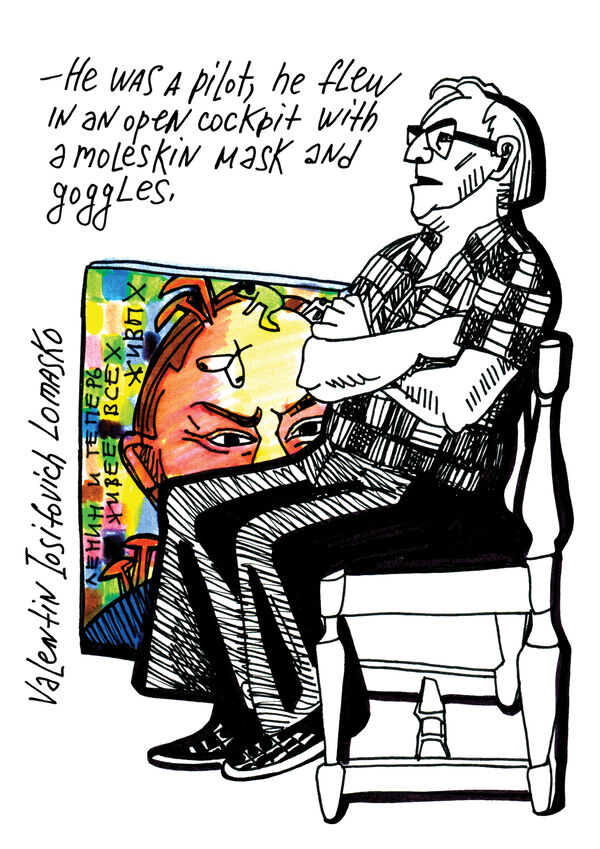

Valentin Iosifovich Lomasko, 80

My father calls himself an artist and a freethinker. For many years, in order to survive, he worked as a designer of Soviet propaganda, which revolted him. When the Soviet Union fell apart and designers like him were no longer in demand, he started making paintings that criticized both the Soviet and Putinist regimes.

Because my father was born during World War II, every month he receives a benefit for “children of war” in the amount of 1,000 rubles (about $14). When their house was bombed during the war, the family moved into the belfry of the Raspyatsky Monastery. In his memoirs, my father wrote that they “lived like animals, on a dirt floor, without beds.” Then, two things happened almost simultaneously: My grandfather Iosif was kicked out of the army, and he divorced my grandmother, abandoning her in the ruins with their three small children.

For years, I asked my father about my grandfather, trying to learn anything I could.

“Papa, why was Grandpa named Iosif, and his mother’s last name Lisovskaya?”

“Because they were non-Russian.”

“Papa, why was Grandpa kicked out of the army?”

“Must have been his nationality.”

“Papa, I read about the place where you said he was born. It’s on the border of Poland and Belarus—mostly Jews lived there. Was Grandpa a Jew?”

“Iosif was a non-Russian bastard!” my father cries out. He cannot forget the hunger of his childhood, he hates the Soviet state, the father who abandoned him, and every last Jew to boot. When he doesn’t like something, he always says, “the Jews did it.”

On the 70th anniversary of Victory Day, my father suddenly declared that my Grandpa Iosif also fought the Nazis.

This was how, at the age of 37, I learned that my grandfather had started out as a pilot, and then became a military airplane mechanic at Drakino, a small base near Serpukhov. When I was a teenager, I was drawn to Drakino like a magnet. I’d lie on the ground there for hours, watching the airplanes doing loop de loops.

I have only one small photo of Grandpa Iosif. Sometimes, when I look at myself in the mirror, I see him. We have the same asymmetrical face, the same uncompromising expression.

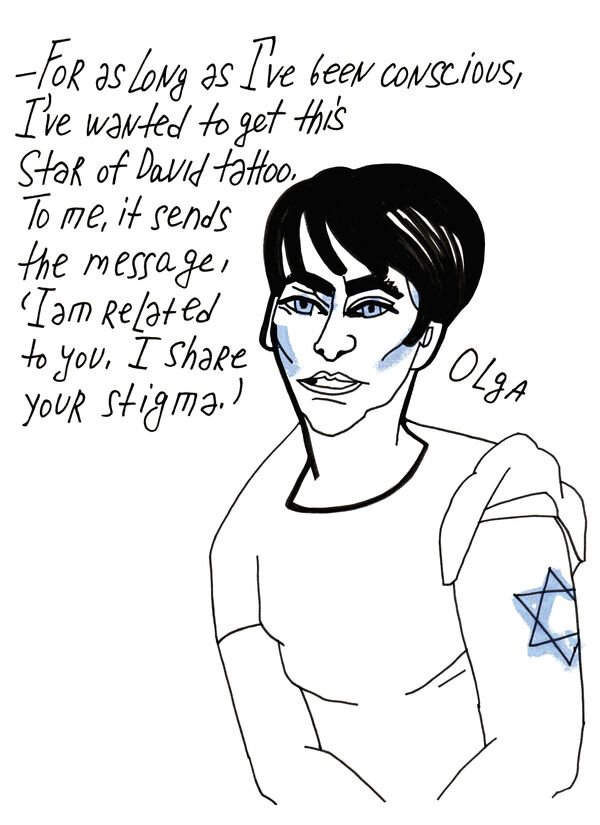

Olga Akhmetieva, 45

Many of my peers have discovered a similarly exiled and forgotten figure in their family trees—mysterious characters with surprising names whose origins our parents refuse to explain.

The only trace my friend, the poet Olga Akhmetieva, has of her grandfather is the same sort of tiny passport photo I have of mine, and a story told by her grandmother.

“My Russian grandmother was in exile when she met my grandpa and had her only child—my mother, Emma,” Olga says. “Why my grandma was in exile, why my grandpa was out there, no one knows. His name was Mikhail Stepanovich (actually Samuilovich) Samsonov, and his mother was Dora Israelivna. My guess is that ‘Samsonov’ is a made-up last name. We don’t have any of his documents.”

“But why are you so sure that your grandpa was a Jew?” I ask Olga.

“It’s in my blood,” she says. “One time, on Pesach, I went to the synagogue on Pokrovka Street. When I saw women sitting outside on the street, I thought they were like the Russian women who beg in front of churches. Instead, they gave me matzah. They said, ‘That’s our girl, eat up.’ I was so shocked that they accepted me. The older I get, the more I look like a Jew.”

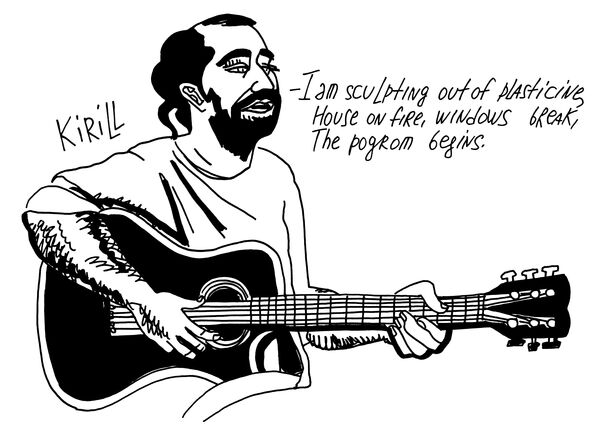

Kirill Medvedev, 46

As I was writing my Jewish essay, I happened to hear that an acquaintance of mine, the famous poet and leftist activist Kirill Medvedev, had recently learned from his parents that his great-grandfather—the Hungarian poet and revolutionary Zoltán Pártos, who inspired Kirill’s approach to art and activism—was “most likely a Jew.”

Kirill was not particularly interested in talking to me about this. He said he’d never thought of himself as a Jew and no one around him did, either. He said there was “only one Jew in the family, my mother’s father, and other than him, there were no Jews in the lineage anywhere.” Although a little later, Kirill remembered that his maternal great-grandmother Olga Solomonovna had once told him that “during the war on cosmopolitanism, people had thrown her off a bus.”

It was hard for me to press Kirill on these questions. Who am I to demand answers when I also grew up in a Russian family—my only connection to Jewishness a grandfather I never knew, who was “most likely a Jew”? And even if I knew for certain that he’d been a Jew, what would this change for me in the present?

“It doesn’t matter to me whether Zoltán Pártos was Hungarian or Jewish,” Kirill said. “I’m interested in the fact that he was a revolutionary, a poet, and a doctor—in the different sides of his persona.” I listened to Kirill, and his words resonated with me. Knowing that my Grandpa Iosif had been a pilot so inspired me that the question of his nationality lost meaning by comparison. “If I am interested in anything about Jewishness, it’s the tradition of leftist Jews who always wanted to get away from their national roots, and because of this energy, became internationalists,” said Kirill, citing the Marxist writer Isaac Deutscher’s essay “The Non-Jewish Jew.”

Before we parted ways, Kirill sang me a song he’d written to accompany the poetry of our mutual friend, the artist Haim Sokol:

When I got home, I found “The Non-Jewish Jew” online, in Kirill’s translation. It begins with a retelling of a midrash: Jewish heretic Elisha ben Abuyah, also known as Acher, reaches the ritualistic boundary that one is forbidden to cross on the Sabbath, and crosses it. Deutscher believes that because Jews have always lived at the intersections of various cultures and religions, belonging to multiple societies at once, they have always been natural boundary-crossers.

I see the similarity between Zoltán Pártos, an activist in the Communist International who immigrated to Moscow from Budapest, and Iosif Lomasko, who left a sleepy village on the edge of Belarus to become one of the country’s first pilots. I see the similarity between Kirill Medvedev—a poet engaged in political struggle, whose books have appeared in dozens of languages—and myself, an international artist whose work about contemporary Russian society is not exhibited in Russia for political reasons. I see the connections between us and our daring ancestors.

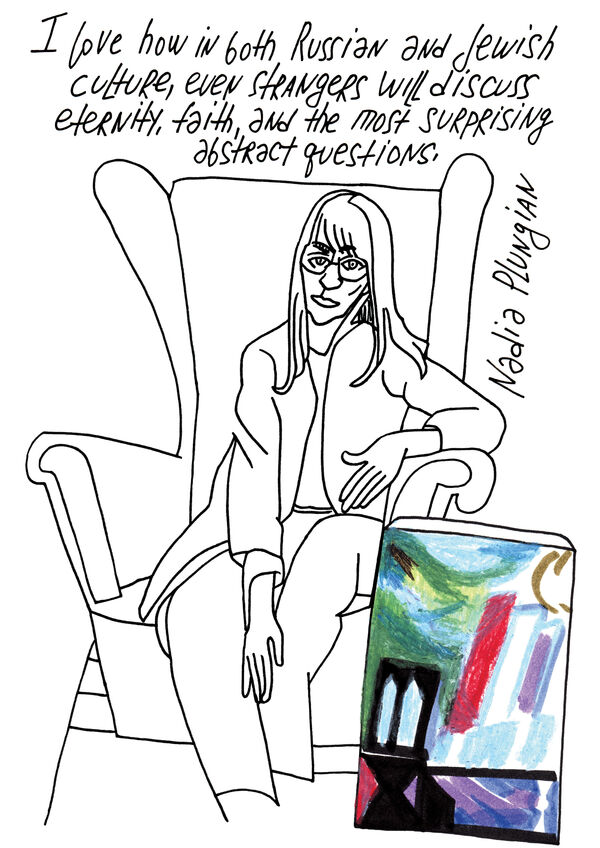

Nadia Plungian, 37

The other day, I stopped by my dear friend Nadia’s house. She’s an art historian and artist, and she showed me the latest painting she’d started, titled Jewish Painting. On first glance, it appears to be abstract. But it is actually a “cipher,” as Nadia calls it, for a landscape of Jewish shtetls, including a ruined synagogue from the Rashkov shtetl in Belarus. I thought it was beautiful how the ruins of the synagogue rhymed with my ruined belfry. Russian and Jewish culture seem to share an affinity: The material side of the world always proves itself tenuous and unreliable, which brings the mystical to the foreground.

Nadia’s family never talked about Jewishness. She didn’t begin to learn about it until she was 16, through conversations with friends and then her grandfather. Eventually, she started studying Jewish culture on her own.

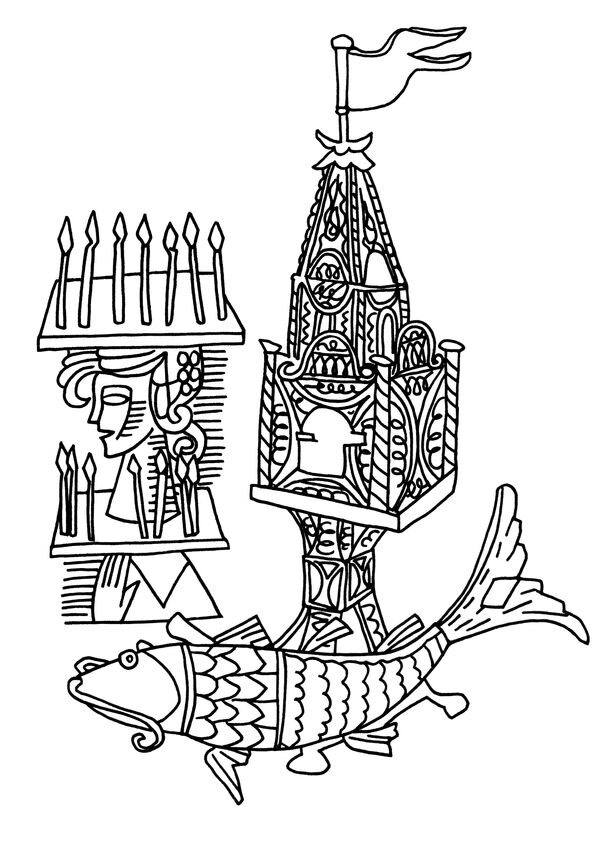

This year, Nadia put together an exhibition called Wandering Stars: Soviet Jewry in Pre-War Art, the first of its kind in Russia. During the 1930s, a new genre of anti-religious exhibitions began appearing in museums across the USSR, in which religious paraphernalia, including Jewish ritual objects, were placed alongside anti-religious propaganda. Nadia also included Jewish ritual objects in her show, only now, they were juxtaposed with modernist Soviet paintings by artists with Jewish roots. The exhibition functioned as a single installation: It became apparent to viewers that these sculptures, mock-ups for theater sets, and, of course, paintings—from abstractions to landscapes to portraiture—referred implicitly to imagery from Jewish culture and religion. I sketched the similarities between the fantastical constructions of the painter and set designer Alexander Tyshler and baroque besamim boxes, which hold spices used in ritual.

Hana Korchemnaya, 32

Many of Moscow’s artists and activists have Jewish roots, but few want to talk about them. Who could I interview for my Jewish essay? I started running through the faces of my acquaintances. When Jewishness isn’t discussed, its traditions aren’t preserved, and last names are changed, what else can you do but trust your gut? I remembered Hana Kochetkova, a famous LGBT activist and psychologist at an NGO called the Women’s Crisis Center. We’d only crossed paths once, at a feminist event, and I didn’t know much about her, but her face reminded me of one of Marc Chagall’s self-portraits, where he painted himself with lucent eyes, soft curls, and a shtetl house on his head. But for some reason, I couldn’t track Hana down by name on social media.

“Five years ago, I started using my maternal grandmother’s last name, Korchemnaya,” she explained when we finally met. “I officially changed it this year.” At some point, her Jewish grandmother destroyed all her documents and started passing herself off as Ukrainian in order to try for a better job. Now Hana (born Anna) has started reversing the process, taking back Jewish names. Over the course of ten years, she has done genealogical research on the online forum Jewish Roots, and has mapped out her family tree back to the late 18th century.

“Until I was 23, I thought I was an ugly Slavic woman with a big nose,” Hana said. “One day, after googling my grandma’s last name, I came upon some information about a Jewish man with the same last name who’d been a victim of Stalinist repression.” Hana’s mother and grandmother begrudgingly answered her questions. “Yes, we’re Jewish,” they told her. “But what good does that do you? You’ll get in trouble at college, we’ll get in trouble at work.”

A little while later, Hana came out to her family and introduced them to her girlfriend. “It went terribly,” Hana said. “But it made me realize something: They probably can’t accept me as a lesbian because of how hard it is for them to accept themselves as Jews. I started studying Jewish history and talking about it with them so that one day, we’ll have a language for addressing both stigmas. One of my relatives wouldn’t even say the word ‘Jew’ aloud before, and now that has changed. I’ve reestablished connections that have been long-forgotten by almost everyone in our family, gotten in touch with people not only in Russia, but also in Germany, Israel, America. Now, I’m realizing how big and diverse our family really is.”

Galya, 21

I wanted to talk to someone for whom Jewishness wasn’t just a nationality, but also a religious identity. Friends of friends put me in touch with Galya, a 20-year-old woman from a Jewish family who is currently studying Judaism. On my way to meet her, I imagined an austere girl in a dark skirt that fell below her knees in an apartment typical of the Moscow intelligentsia, with bookshelves up to the ceilings. Galya, a tiny woman in harem pants, sat cuddled with her boyfriend on a mattress on the floor of a nearly empty apartment. More than anything else, she reminded me of a typical young person from Moscow’s protest movement, the kind I’ve been drawing at demonstrations for the past several years.

“And you’re probably a feminist?”

“Of course I am, who isn’t?”

“Do you protest?”

“Of course I do!”

It turned out that we had a few activist friends in common.

Galya’s parents had never concealed their Jewishness, but they also didn’t have any interest in performing it. She returned to tradition independently, with the support of peers who were on the same wavelength. Galya read to me in Hebrew from a book she held in her hands.

“What does it mean?” I asked her.

“When the Lord delivers the children of Zion from bondage, all we have lived through will be as though we had dreamt it.”

“Where is it from?”

“It’s Psalm 126.”

A long time ago, when I was searching the name Lomasko on various Jewish websites, I came upon a religious resource for Russian-speaking Jews. I didn’t find any genealogical information, but Judaism turned out to be a lot more interesting than the question of my family tree, and I kept on visiting the site for almost a decade, watching lectures and reading message boards. The rabbis’ lectures destabilized the material world, creating the sensation that it was something more porous, permeated with mysterious light. I asked a few questions through the portal, but the rabbi’s answers made it clear to me that I don’t have the resources or the community support to go deeper into Judaism. My personal door into that magical realm is art.

Galya doesn’t know where she’ll ultimately end up. Right now, she is a student in Germany, where she’ll soon return. She described her relationship to Russia as “learned helplessness,” and she told me she’s sad that she “can only marry one person to get them out of here.”

“It would be better if there wasn’t another revolution here since that inevitably means violence, which I am always trying to avoid,” Galya said. “But I also don’t have any hope left for incremental change.”

While I listened to Galya talk about Russia, I returned in my mind to the image of the windswept ruins, impossible to live in. But when I look at Galya, I see her as a new kind of flower that could never have sprouted in my generation, much less my father’s. My father’s generation was concerned with basic survival; they were desperate to pass for “typical Soviets.” Galya’s generation just wants an easy and happy life; they take diversity for granted. On the one hand, my father and Galya are as different as citizens of two different nations—the USSR and Russia, respectively. On the other hand, there is a kind of continuity.

This “Jewish essay” proceeds in something like a gradient, from a dramatic navy blue to a tender green, from an overlong winter to a budding spring. Everyone I spoke to, including my furious father, holds their seed of knowledge. If we let the seeds take root, we may yet see a garden bloom from the ruins.

Victoria Lomasko is a Russian artist whose work is based on the synthesis of text and images. Her book Other Russias, a collection of “graphic reportages,” was published in six countries, including by n+1 Books in the US and by Penguin in the UK.

Bela Shayevich is a visual artist, writer, and translator best known for translating Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time. Her latest book is a translation of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We. She is currently a student in the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa.