A Shabbat for All Creation

Selections from Perek Shirah set to music testify to the holiness in all beings.

When the pandemic arrived in March 2020, I’d spent much of the previous five years as a touring musician. While for millions the quarantine brought anxiety and claustrophobia, my wife and I—outrageously blessed, living on a sprawling, grown-over tree farm in rural Kentucky—had the space and time to luxuriate in a rest that we never would have taken for ourselves. Threading our daily lives into the rhythm of the land, we went a bit feral—inhabiting an exquisite sense of peace, of holiness.

It was during this period that I first encountered Perek Shirah (Chapter of Song), a mystical Jewish text that dates back to at least the 10th century, in Gershom Scholem’s Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. In this “brief tract,” Scholem writes, “all beings are gifted with language” so “they may sing . . . the praise of their Creator,” thus expressing “the prophetic vision of a redeemed world, in which all beings speak in hymns.” I immediately bought a bilingual edition.

Across six chapters, Perek Shirah features 84 natural elements and beings—from the heavens and the earth to the dogs and the rats (or, in some translations, weasels)—each one singing a selection from a sacred text: mostly psalms, but also snippets from Torah, Talmud, and elsewhere. In some cases the relationship between singer and song is obvious (the raven sings of the hungry raven whose “young cry out to God” at the end of Job 38, the snail of the melting snail to which the wicked are compared in Psalm 58), but in others the connection is more mysterious. The frog, for example, gets this familiar line from the Shema: “Blessed is the name of his glorious kingdom for ever and ever.” From my self-guided survey, most available commentaries on Perek Shirah suggest that the moon, the locust, and the fig are little more than didactic vehicles for scripture, the singers of the natural world an almost trivial conceit. But this approach may miss the true brilliance of its vision. Perhaps these songs aren’t simply expressions of piety, but acts of mystical translation, revealing the nonhuman connection with the divine through the human medium of language. Against an anthropocentric Judaism, Perek Shirah testifies to the holiness in all created things.

In fact, the Torah teaches that it is not only human beings who have a covenant with God. After the biblical flood, God fixes a rainbow in the clouds and, vowing to never again unleash his annihilative wrath, declares that “every living creature” and even “the earth” are bound by the same covenant as humanity (Genesis 9:12–13). We later learn that just as we have a weekly Sabbath, every seven years the earth has a Sabbath of its own: the Shmita year “of complete rest for the land” (Leviticus 25:5). Considered against this backdrop, might Perek Shirah, by spreading scripture beyond the human sphere, suggest that every plant, animal, and natural element has a covenant with God? What if, just as the rat and the dog each sing their own hymn, they are also owed their own Shmita—a reprieve from stress, exploitation, endangerment? A Shabbat for all creation.

Over the Shmita year that ended this past Rosh Hashanah, a period marked by innumerable crises, I turned to Perek Shirah for comfort. I developed a practice of meditation and interpretation, which took shape in musical arrangements of some of its songs, typically composed around dawn, while my wife and baby daughter were still asleep. Accompanied only by birdsong, I could tap into a sense of tranquility and union with the natural world. These compositions set the Hebrew scripture within longer instrumental passages, the wordless music attempting to represent the mystical presence of the nonhuman, accessible but never fully intelligible to human ears.

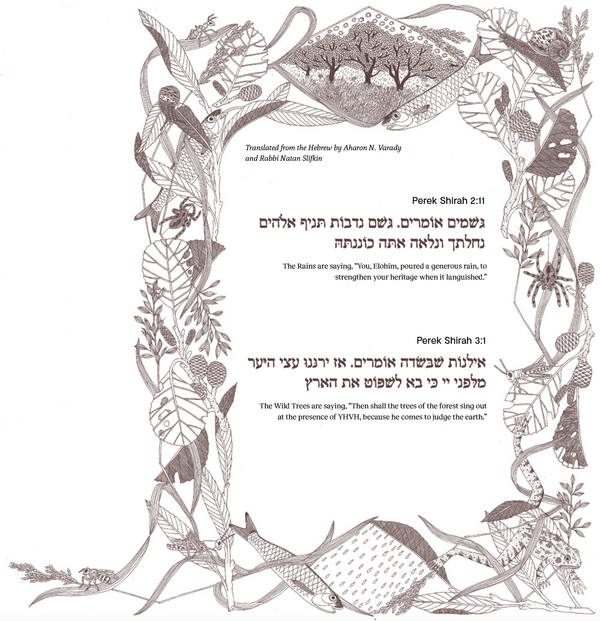

Offered here are two sketches—“Perek Shirah 2:11 (The Rains)” and “3:1 (The Wild Trees)”—composed of guitar and voice, sung by my friend Noa Babayof. I hope they transmit the spirit of this peculiar and numinous text, and perhaps some semblance of the peace I felt at work on them.

Guitar recorded by Jim Marlowe, End of An Ear, Louisville. Singing recorded by Uzi Katz, ComboMusic, Be'er Sheva. Mixed by Jim.

Nathan Salsburg is a guitarist, composer, and the curator of the Lomax Digital Archive. He currently lives in Kentucky.