ISRAELI PRIME MINISTER Golda Meir once said there is no such thing as Palestinians. Later, in a 1976 New York Times op-ed, she claimed to have been misquoted, writing that what she actually said was: “There is no Palestinian people. There are Palestinian refugees.” She may have found the distinction comforting, but the underlying assertion is the same and no less pernicious. It suggests that the Palestinians’ expulsion from Israel is the only trait that distinguishes them from other Arabs, and that the idea of a unique Palestinian people, with their own culture, is a political fiction.

This argument has a long half-life. It lurks in discussions of Israel/Palestine, whispered in the living rooms of liberal Zionists, and proclaimed by right-wing politicians in the halls of government. During an insult-laden speech to the Israeli Knesset last year, Likud MK Oren Hazen doubled down on Meir’s idea. “There is no Palestinian people and there never has been a Palestinian people.” The claim is aided by the erasure and appropriation of Palestinian culture and history. As part of its national project, Israeli culture subsumed traditional Palestinian food such as hummus and falafel, and even the folk dance dabke. Arabic villages were given Hebrew names. Synagogues replaced mosques. The traces of Palestinian culture and history were swept away.

A new museum of Palestinian art and culture in Connecticut provides an unassuming corrective to this form of historical erasure. Located in Woodbridge, just outside New Haven, the Palestine Museum US strives to present the story of the Palestinian people to the American public, and to serve as a cultural center for the American Palestinian diaspora living in the United States; it is the first space of its kind in North America.

I visited the museum on an overcast Sunday, driving past the woods and strip malls encroaching on this affluent suburb. At the museum’s address, I found a multi-story office building that seemed out of place amid the green fields and forests. A small sign affixed to the door read “Palestine Museum US,” and the museum’s founder, Faisal Saleh, was waiting in the lobby. A friendly, avuncular man with a bushy salt-and-pepper mustache, Saleh gave off an air of formality. Before showing me around, he asked me to sign in using a mini-iPad. “We just started using it today.”

The museum itself comprises a sprawling area previously home to cubicles and conference tables. Paintings, sculptures, photographs and historic objects now fill the warren of interconnected rooms replete with office-grade grey carpeting. In one gallery, mannequins model traditional Palestinian dresses, emblazoned with intricate embroidered patterns. In other rooms, colorful paintings cover the walls, some figurative, some abstract.

The artwork on display was mostly made by Palestinians living in the West Bank, Israel, or Gaza. Getting art out of Gaza can be problematic because of the Israeli blockade; pieces need to be ferried out by diplomatic missions or taken (sometimes smuggled) through checkpoints and shipped from Egypt or the West Bank. But this hasn’t deterred production. Saleh tells me that Gaza has more artists than anywhere else he’s ever seen, as “people have a lot of time.” Youth unemployment is around 60%, and the 1.8 million people who live there—who are mostly under the age of 24—are unable to leave. For some, art is their only escape.

Eighteen-year-old Malak Mattar is one such young artist from Gaza. The exhibition features several of her paintings—rough, vibrant portraits that mix echoes of Modigliani with geometric patterns and floral motifs. She started painting when she was 13, during the brutal 2014 Israeli assault on Gaza that flattened 20,000 homes with artillery and air strikes and killed over 2,000 Gazans. Unable to go outside for two months, Mattar painted to deal with the terror and anxiety. She has since honed her skills, garnering international praise by posting her work online and mounting several shows around the world—which she could not attend due to the blockade.

In the first room that Saleh took me to, large black-and-white photographs of the Palestine Mandate hung on the wall, a vision of a lost world: fashionably dressed men and women attending political rallies and social events, or waiting at British checkpoints. We stopped in front of a large image of sheep grazing in an open field, and Saleh told me that unlike the sheep in the US, Palestinian sheep don’t have tails, but instead have “pieces of fat” hanging where the tails should be. “You can see them hanging in the butcher shop.” It is one of the few times he talks about Palestine without the remove of having left almost 50 years ago.

Saleh’s parents lived in the village of Salama just outside Jaffa, a Palestinian port city just south of Tel Aviv. They were forced out during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and lost everything they owned. They settled near Ramallah, 30 miles to the east, where Saleh was born and raised. When he was 18, he left and moved to the United States to finish his senior year in high school. He then went on to study at Oberlin, marry an American woman, and embark on a successful career as an entrepreneur, founding a software company and consulting business. His parents moved to Abu Dhabi in 1970. The last time Saleh visited Palestine was in 1999, shortly before the Oslo Accords came undone.

Though he has stayed out of the politics of Israel/Palestine, Saleh has long wanted to do something for the Palestinian people. Before opening the museum in Connecticut, he was involved with a group trying to create a Palestinian museum in Washington DC. Over time, however, he grew disillusioned with the pace and orientation of their project. “They really wanted to present a diluted version of the Palestinian story, one that doesn’t offend anybody.” Saleh felt differently. “The facts are the facts,” he said, “if somebody gets offended, I’m not concerned about that.”

After giving up on the DC museum project, Saleh struck out on his own, with a few like-minded collaborators. He decided to use a building he owns, the Connecticut office complex, to house the fledgling museum. He has largely funded the project himself. He hired an architect to redesign a wing of the office building and, with a few volunteers, started cold-calling artists. It was slow-going in the beginning; each call took a lot of explaining and convincing. Then Saleh reached the well-known Palestinian artist Samia Halaby and asked her to contribute. “She was skeptical at first,” Saleh said, but the 81-year-old painter ended up visiting the museum, and agreeing to loan artworks to the inaugural exhibition—three colorful, almost geometric paintings that dominate one of the galleries. Once Saleh told other artists that Halaby was involved they were eager to contribute work. They were able to complete the museum and mount the first show in just ten months.

The museum opened in April of this year with live music and a keynote speech by Halaby. One of the museum’s anterooms features a floor-to-ceiling mural by Ayed Arafah, a Palestinian artist based in the West Bank, of the American activist Rachel Corrie, who was killed by an IDF bulldozer in 2003. The mural recreates an iconic photograph of Corrie, staring levelly into the distance, superimposed over a tableau of her in front of an armored bulldozer, trying to block it from razing a Palestinian home. Corrie’s parents, who live in Olympia, Washington, came to the opening to see the dedication of the mural.

Saleh started the museum on a Field of Dreams model, wagering that general interest and Palestinian Americans’ thirst for their own culture would bring people to this remote location. (For now, the museum is only open on Sundays.) He hopes, however, that this first incarnation will build enough support (both culturally and financially) to expand the museum and move it to a larger city such as New York or Philadelphia. Few such venues for Palestinian culture exist in the world. There is a small museum and social club in Bristol in the United Kingdom and, of course, the official Palestine Museum in Birzeit in the West Bank, which opened without any exhibits in 2016 due to logistical problems and a dispute between the board and the director. It is a large vacuum for a museum in suburban Connecticut to fill. For now, Saleh and the volunteers at the museum are focused on promoting their new project and developing the next exhibition, which will shine light on the Palestinian refugee camps scattered around the Middle East.

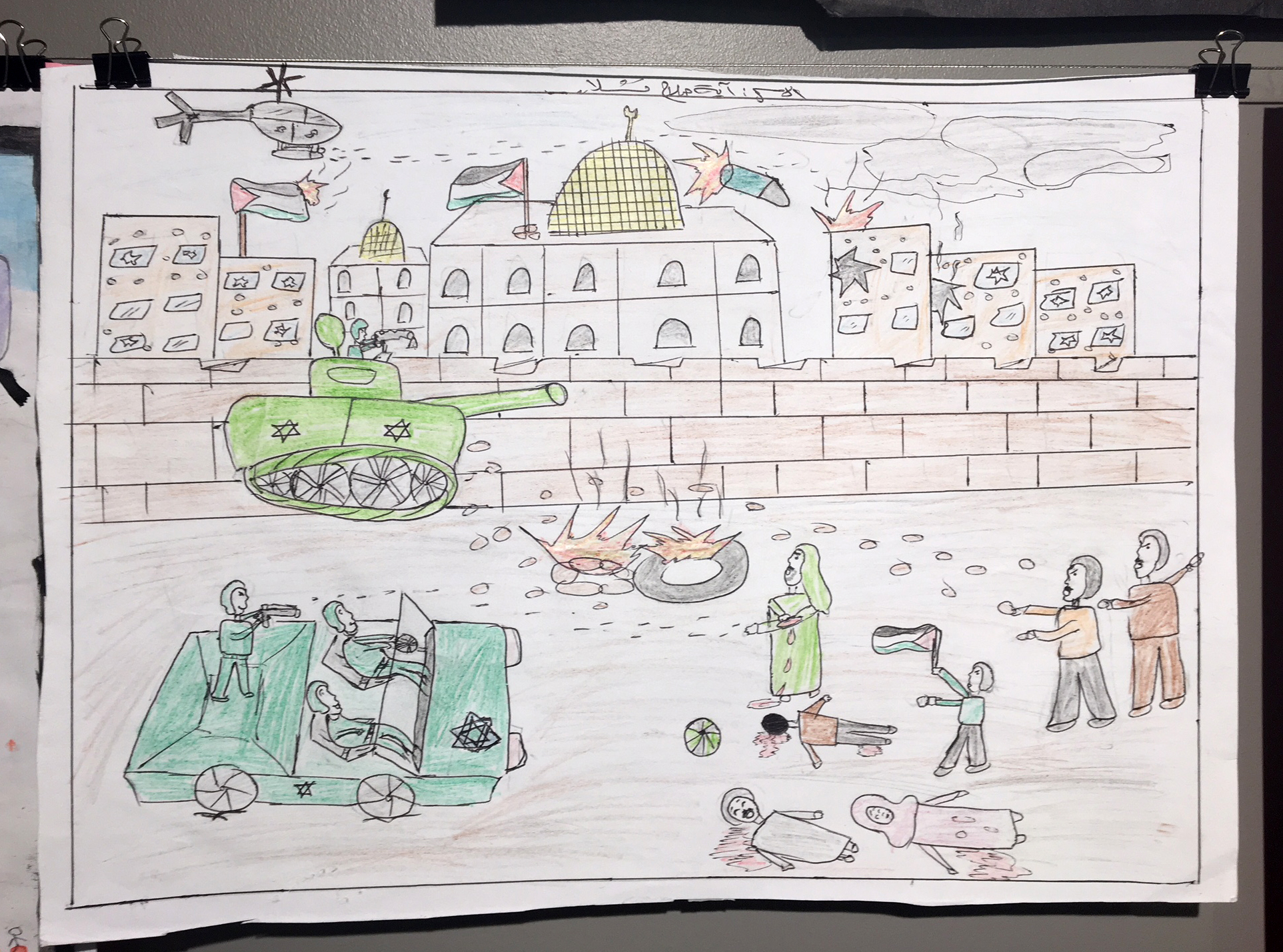

In the back of the museum, Saleh showed me a collection of children’s drawings, affixed to lines of wire with binder clips, covering one wall of the room. The drawings were made as part of a therapy project named Let the Children Play and Heal that helped young Gazans deal with trauma from the 2008 Israeli incursion. In 2011, the Museum of Children’s Art in Oakland planned to exhibit these drawings, but cancelled at the last minute because of pressure from local Jewish groups and the Anti-Defamation League.

The drawings are heartbreaking, their subject matter disturbingly uniform. Israeli helicopters and jets fly overhead, shooting oversized bullets and missiles. Below, childish bodies lay, bleeding large drops of blood amid broken buildings and fires. The picture I found most disturbing depicts not the brutal attacks, but a ship offloading cargo in a port. The ordinary, almost boring, scene seems to cry out for normalcy.

Despite the subject matter and context of the work on display, Saleh insists the museum’s goal is not political. “Our objective,” Saleh said, “is to change the discourse from the political arena to the artistic and cultural arena. And to show that Palestinians are humans, entitled to human rights, and to be treated with respect and compassion.”

It is true that the project is a simple act of cultural history. But culture is never neutral, and neither is history. Supporters of Israel still contest that there ever was a distinct Palestinian people, as if recognizing Palestinians as anything other than bare life would threaten Israel’s very existence. But what is a people if not shared culture, trauma, and aspirations? Manifested in art and historical objects, this is the purpose of the Palestine Museum US. The works are not presented as political or geographic claims (those, perhaps, are self-evident), but rather as a demand to be seen as more than simply refugees or terrorists. It is a demand to be recognized as a people, not for the land stolen from them but for the richness of their culture, the depth of their history, and the validity of their dreams.

Michael McCanne’s work has been published by Art in America, The New Inquiry, Boston Review, Jacobin, and Dissent.