Shirley Wegner’s Unsettled Landscapes

In Wegner’s photographs, we are looking not at historic events but at collective memories.

IN AN 1899 ESSAY, Sigmund Freud theorized that the mind uses intense, seemingly random childhood memories to eclipse foundational traumas. These “screen memories,” as he called them, form out of an amalgam of real experience and imagined or adopted imagery, sublimating and obscuring memories of formative traumatic episodes.

Shirley Wegner’s landscape photographs are, in their own way, collective screen memories: landscapes imbued with displaced trauma and conflict. Like memories, the photos are slightly warped; at first glance they unsettle the eye. Their lines appear soft, as if they’ve been run through a digital filter, or painted over in oil. It is only on a second pass that you realize the photographs themselves are untouched, but the landscapes they depict are artificial, built with papier-mâché, cloth, and painted wisps of cotton. Some are uncanny in their verisimilitude while others look like oversized dioramas. Several of the images depict empty spaces, construction sites, and eucalyptus groves, while others are dominated by the interchangeable and anonymous aesthetics of destruction. Fires, explosions, and ruins fill the frame. In a series of night images, lights populate the horizon as glowing columns of smoke billow overhead, issuing from flames on the hills. The circumstances are unclear. We are looking not at historic events but at collective memories, with Wegner serving as the prism. “The photographs I build,” Wegner explains in an artist’s statement, “are made with no visual reference but my own memories of images as I may have seen them in books, old TV shows, black and white photos, historical museum leaflets or family albums.”

Wegner was born and raised in Israel, and her set pieces mostly reconstruct the fraught landscape of her homeland and gesture toward its complex—and conflictual—underlying narratives. Several of the photos contain signifiers of the land and the Israeli state: green bunches of prickly pear cacti, tractor tracks in the sand, eucalyptus leaves, a watchtower on the horizon, a paneled concrete wall in the distance. The images of violence and ruins could depict scenes from the grand mythologized wars of Israel’s past, or the endless asymmetrical war of its present in Gaza, the West Bank, and Lebanon. But Wegner’s images are bereft of specific historical and geographic context. The images stand instead for a more generalized and detached experience of violence fused with a personal nostalgia for the land.

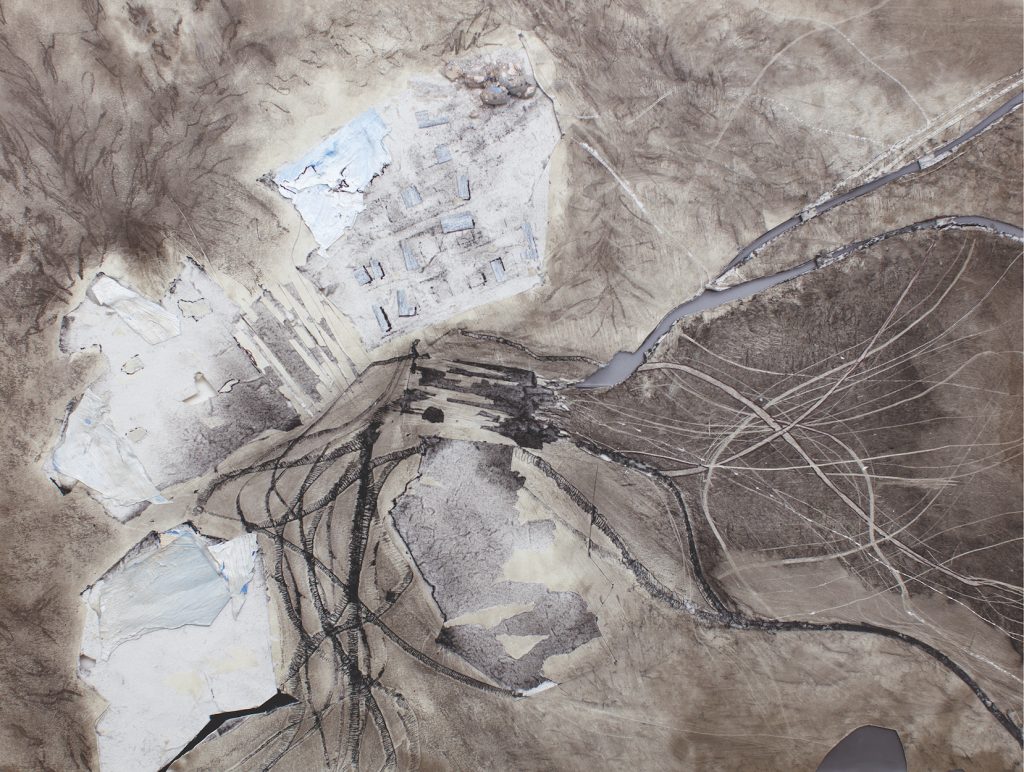

The work not only calls into question the role of memory in constructing the narratives of place but also the role of photographs in constructing reality. In a series titled “Aerial View,” Wegner has created imagined landscapes as seen from above, mimicking the ultimate expression of photographic power: the satellite image. In these ghostly photographs, tiny paper shapes represent buildings against near-monochromatic backgrounds, scratched and burnished with charcoal and light brown inks. Fields and roads make familiar patterns, dividing the frame, and buildings populate the space as small rectangular shapes. The sense of looking from a great distance above evokes drones overhead: silently drifting, watching, hunting. This aesthetic choice reminds the viewer that photographs not only create narratives; they also record, quantify, and surveil.

Wegner’s current exhibition at the Rosenfeld Gallery, Tel Aviv, entitled The Unphotographed—a nod to Freud’s theory of the uncanny—features recent work that digs deeper into the discordance between artifice and reality in photographs. Several images explore the medium more formally, attempting to replicate the imperfections of the camera or the color gradient across a photographic test strip. In one image, illuminated colored strings replicate digital distortion on a night shot. Another depicts a gray-scale field solarized by a digital filter. These faux imperfections emphasize the image-making technology that has come to dominate how we see the world. “In the process of constructing the image I often leave traces of how it was made, stripping it off of its seemingly realistic nature, or its mythic photographic power,” she writes in her artist’s statement.

Photographs create distance and intimacy in a singular photochemical process. Their detailed representation offers a sense of being able to experience what the photographer sees. The flatness, on the other hand, allows the viewer to examine the subject at a dispassionate remove. Wegner’s images heighten this tension by introducing memory and artifice into the equation, combining childhood nostalgia for the landscape of her country with a critical understanding of its politics. Her work disturbs the relationship between images, ownership, and memory. It questions how photos reinforce the personal and collective narratives we tell ourselves. The resulting pieces are somber, menacing, and beautiful. They emanate the communal psychic trauma of contested land.

Michael McCanne’s work has been published by Art in America, The New Inquiry, Boston Review, Jacobin, and Dissent.