Yiddishland at the Venice Biennale

Yevgeniy Fiks and Maria Veits discuss the Yiddishland Pavilion, which brought transnational diasporic Jewish art—and anti-nationalist politics—to the Venice Biennale.

Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson and Anna Elena Torres: Pseudo-territory. Image courtesy of the Yiddishland Pavilion.

(This article previously appeared in the Jewish Currents email newsletter; subscribe here!)

For the 59th iteration of the Venice Biennale, a world-renowned international exhibition of art and culture, artist Yevgeniy Fiks and curator Maria Veits embarked on an ambitious curatorial project: the Yiddishland Pavilion. As Fiks and Veits write, this is “the first independent transnational pavilion bringing together artists and scholars who activate Yiddish and the diasporic Jewish discourse in contemporary artistic practice.” The project was not an official part of the Biennale and did not consist of a literal pavilion. Rather, it appropriated the Biennale’s terminology, intervening in the very structure of the event—which is organized around national pavilions—by taking place as “a fluid and nomadic project” that spanned the space of the Biennale and also unfolded online. It’s a fitting form for addressing Yiddishland, which Fiks and Veits describe as “an imaginary country/land/space/territory and a stateless network connected through the Yiddish language and culture.” In artworks, performances, and events that took place between April and November 2022, the Yiddishland Pavilion, which included Jewish and non-Jewish artists from around the world, explored contemporary artistic uses of Yiddish culture, while also addressing broader themes of migration, political exclusion, and anti-nationalism.

I spoke to Fiks and Veits about the pavilion and the curatorial philosophy behind it. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Stanislaw Welbel: How do you understand the term “Yiddishland”?

Yevgeniy Fiks: In one sense, Yiddishland is an alternative map of Eastern and Central Europe—a way of naming the space where the Yiddish-speaking Jewish community lived during the last millennia. But as Yiddish speakers have become more dispersed, the concept has expanded beyond that geographic area. Now there are clusters of Yiddishland in the United States—most obviously in New York City—but also in Mexico, Argentina, Israel, and elsewhere.

Maria Veits: And in terms of our project, Yiddishland is not just a geographic location, but also a shared space tracing and preserving contemporary Yiddish art, performance, and culture. While working on this project, we talked a lot about what it means to represent Yiddishland, as a “country” that has existed metaphysically—and still does, despite many attempts to erase it—but which has never actually existed geographically. We wanted to bring together many different, dispersed parts of Yiddishland and connect them all within the physical space of the pavilion, as well as online.

SW: What was behind the decision to do this project at the Venice Biennale?

YF: The Biennale felt like an obvious setting for a project that asks where the Eastern European Jewish story fits into the European narrative, because the event is so marked by the “great powers,” down to the physical layout—“major” nations claiming big, beautiful buildings, and smaller or newer nations renting villas in the city.

MV: At the same time, we didn’t want to reproduce the principle of national division that is embedded within the structure of the Biennale. The Yiddishland Pavilion was an attempt to challenge this logic, which reinscribes a hegemonic view of the world order. This is especially apparent in moments of geopolitical transformation: For example, Russia inherited its pavilion from the Soviet Union, while no other former Soviet republics received a permanent pavilion on the premises or managed to get official representation until decades later. The same thing happened with the Yugoslavian pavilion—after the collapse of the country, the building was taken over solely by Serbia.

To contest this nationalist structure, the Yiddishland Pavilion was not concentrated in one space. As much as possible, it was dispersed across the Biennale grounds, from the German pavilion—the site for artist Ella Ponisovsky Bergelson and researcher Anna Elena Torres’s augmented reality sculpture, which appears superimposed over an exhibition space when viewed through the Yiddishland Pavilion’s website—to the area in front of the Polish and Romanian pavilions, where dancer Avia Moore conducted her series of collective Yiddish dance performances during the opening weekend.

Avia Moore: Take My Hand: Yiddish Circle Dances in Venice. Image courtesy of Yiddishland Pavilion.

SW: In addition to undermining the logic of the Biennale by intervening in several national pavilions, the Yiddishland Pavilion also created its own space online. What did that virtual space make possible?

MV: It gave us much more freedom in terms of what we could do, and it also made the project far more accessible to people outside the usual Biennale audiences. The online dimension meant that the pavilion could float between these two worlds—it has one foot in the Biennale’s framework and the other in this global realm.

The projects that are virtual could even be viewed in the pavilions they’re connected with, which created an alternative experience of the Biennale itself. For example Hagar Cygler’s textual, audio, and photographic collage, which connects her family’s Polish and Israeli histories, could be experienced both online and in the Polish pavilion by anyone with a smartphone. And with Yevgeniy’s audio walk, which consists of eight chapters tracing the international migration of the Jewish modernist artist Yonia Fain, you could go to the US pavilion or to the Mexican pavilion and listen to that chapter of his life journey there. So these virtual works created an additional layer of perception and feeling on the ground in Venice.

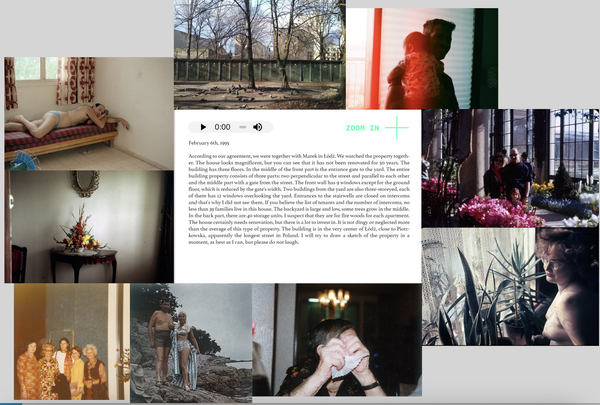

Hagar Cygler: I Will Try to Draw a Sketch of the Property, As Best As I Can, But Please Do Not Laugh. Image courtesy of Yiddishland Pavilion.

SW: Most of the events were in English, and Yiddish was not very present as a spoken language. How did you think about the place of language in the project?

MV: If we had held all of our events exclusively in Yiddish, that would have limited them to a narrow audience, and one that already engages with the kinds of questions we were asking. We wanted to expand the audience for these questions, and to broaden the platform for the artists we featured. We also didn’t want to limit ourselves to participants who know Yiddish. Regardless of their ability to speak the language, everyone we worked with has a relationship to Yiddish culture.

That said, in future iterations of the project, we do plan to include more Yiddish-speaking artists and to have Yiddish be more present as a language.

YF: I think it was Jeffrey Shandler who mentioned that historically, Yiddishland was a multilingual environment: Yiddish was seldom the only language that a Yiddish speaker would speak. So it was also important to us to capture some of that sense of multilingualism.

SW: How did you go about finding the curators, artists, and other collaborators you worked with?

YF: We each had pools of artists that we wanted to bring in—I knew more artists from the US who were working with Yiddish, and Maria knew a lot of Jewish artists working in Europe and Israel. So instead of doing a call for proposals, we just went artist by artist.

MV: One thing that was important to us was that the pavilion didn’t focus solely on “Jewish issues,” narrowly defined. We wanted to highlight artists who were making connections between Yiddish culture and history and contemporary global politics. For instance, Uladzimir Hramovich, an artist from Belarus who now lives in Berlin, created a new video and performance work, which considers the tsar’s repression of Bundist anarchism in Vilna at the turn of the 20th century alongside the Belarussian government’s crackdown following the 2020–2021 protests. We also commissioned a text-based performance by Neue Jüdische Kunst—a duo of Jewish Ukrainian artists, Nikolai Karabinovych and Garry Krayevets—that took on new layers of meaning after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Neue Jüdische Kunst: Yarmulke of a Stretched String. Image courtesy of Yiddishland Pavilion.

SW: To what extent did this war, which is taking place in the very heart of Yiddishland, change the pavilion?

YF: At some point at the beginning of the war, we were considering canceling the project altogether—it felt like it was not the right time for art. But then some friends and colleagues suggested that it was actually exactly the right time for projects like ours, projects that critique nationalism. So we decided to move ahead with the pavilion and added some more events and performances with Ukrainian artists. One of the first events we had in Venice was a panel discussion about Jewish, Latvian, and Ukrainian refugee and diaspora artists called “Map of Refugee Modernism(s),” which considered the impact of war, displacement and exile on the formation of national and global art history.

Right now, Yiddishland is literally on fire. As far as what that means for the Yiddishland of our project, I really don’t know.

Stanislaw Welbel is a curator and art historian based in Warsaw. He works at the Austrian Cultural Forum and is finishing his PhD thesis at the Institute of Art of the Polish Academy of Sciences.