Why There’s No Such Thing as a Jewish Gaucho

The Murders of Moisés Ville examines the violence lurking beneath tales of a Jewish utopia in rural Argentina.

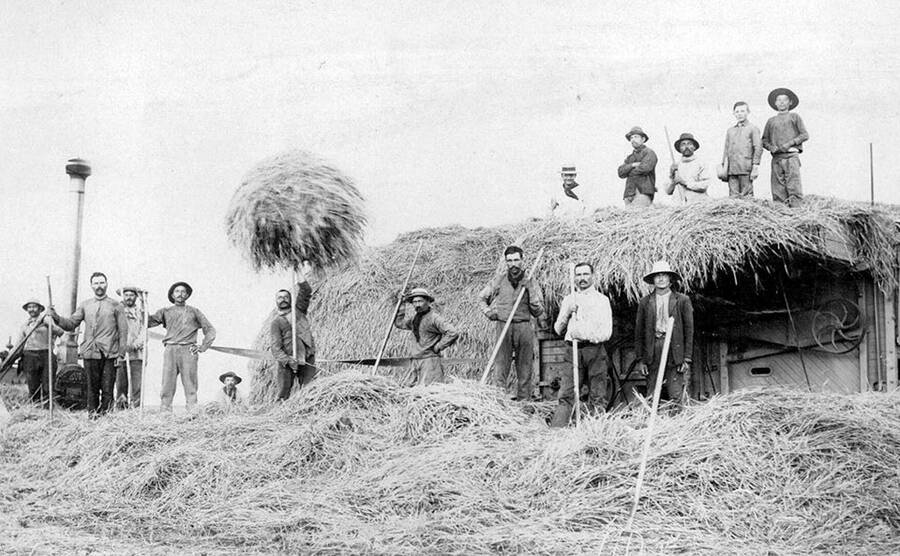

Farmers in Moisés Ville, Argentina.

Discussed in this essay: The Murders of Moisés Ville: The Rise and Fall of the Jerusalem of South America, by Javier Sinay, translated by Robert Croll. Restless Books, 2022. 288 pages.

In 1891, a time of heightened antisemitism and frequent pogroms across the Russian empire, the German Jewish philanthropist Baron Maurice de Hirsch bought 17 million acres of rural Argentine land for Jews to farm. Refugees from tsarist Russia had already started emigrating to Argentina, whose government wanted immigrants to come cultivate its fertile pampas—so much so that it cut a deal with de Hirsch and the organization he founded, the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA), to allow them to acquire land tax-free. De Hirsch distributed these acres to the dispossessed Jews who had begun founding small towns in the rural province of Entre Ríos, hoping that, through farming, they could take control of their fates.

After de Hirsch’s death, in 1896, Jews continued to flock to Argentina: In 1900, the nation was home to roughly 20,000 Jews; by 1920, it held some 150,000. While they found the safety and economic opportunity they needed to build thriving communities, they also faced widespread antisemitism. In 1919, a general strike in Buenos Aires set off a weeklong pogrom known as the Semana Trágica, or Tragic Week, in which the police and military, joined by wealthy right-wing civilians, attacked workers who looked Jewish. One journalist reported seeing “innocent old men whose beards had been uprooted”; after the violence ended, an army commander announced that, of the 193 workers who’d been killed, all but 14 were Jews. Hate speech against Jews remained common in the decades after the Semana Trágica: Street-corner priests spouted antisemitic rhetoric; the writer and editor Jacobo Timerman, who grew up in 1930s Buenos Aires, writes of using heavy wooden ping-pong paddles to defend himself against antisemitic street gangs. In 1976, a right-wing coup unseated President Isabel Perón and installed a military junta that made hatred of Jews unofficial state policy. Though antisemitic sentiment waned after the return of democracy in 1983, Buenos Aires’s Jews suffered the deadliest terrorist attack in the country’s history in 1994, when Hezbollah assailants bombed the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA), one of the city’s biggest hubs of Jewish activity. The attack, sponsored by Iran, killed 86 people and destroyed much of the AMIA library, which held a century’s worth of Argentine Jewish books and newspapers.

In popular Argentine memory, the colonies financed by Baron de Hirsch stand as shining counterpoints to this difficult history—places where Jews flourished without prejudice. The journalist Javier Sinay, an assimilated Argentine Jew descended from JCA settlers, grew up with this sunny image of towns like the one where his ancestors lived, Moisés Ville, which was once known as the “Jerusalem of South America.” His childhood concept of the place emerged not from family lore, but from myths rooted in The Jewish Gauchos, a cozy 1910 story collection by Alberto Gerchunoff, a major figure of 20th-century Argentine letters whose work influenced Jorge Luis Borges. In Gerchunoff’s tales, which were made into a well-received movie in 1975, a group of persecuted immigrants, aided by their neighbors, become happy, prosperous cowboys, known in Argentina as gauchos. As North Americans have long loved the myth of Native Americans teaching the Pilgrims to grow corn, so have Argentines of all faiths enjoyed the notion of rural criollos—a term that describes anyone whose Spanish ancestors arrived before the nation achieved independence in 1816—teaching shtetl Jews to ride.

But Sinay’s 2013 narrative nonfiction book, The Murders of Moisés Ville, recently translated by Robert Croll, highlights the violence lurking beneath these tales of harmony. Moisés Ville’s inhabitants speak of it today as a site of perfect accord between Jews and Christians—and yet, Sinay discovers, 22 Jews living there were murdered in the years surrounding the turn of the 20th century. Sinay decided to reconstruct the stories of these killings after his father stumbled on a partial Spanish translation of an article by the author’s great-grandfather, Mijl Sinay, the editor of a Yiddish-language Buenos Aires newspaper, who described the murders in an effort to raise awareness about the precarious conditions in which rural Jews lived. In his quest to verify the essay’s claims, Sinay learns Yiddish, searches through the uncatalogued remains of the AMIA library, and seeks out the living relatives of Jews killed in Moisés Ville. What begins as an exercise in historical sleuthing evolves into a more ambitious exploration of Argentine Jewish history and identity.

Sinay could easily have positioned the Moisés Ville killings as precursors to the Semana Trágica and the antisemitism of the junta, reinforcing the ubiquitous narrative that the historian Salo Baron calls the “lachrymose conception of Jewish history,” which presents the Jewish story as one dominated or defined by suffering. Rather than assimilate the sad fates of the Jews murdered in Moisés Ville into this too-familiar framework, Sinay confronts the true impetus for the killings: not antisemitism, but the ethnic tension and class conflict that arose when European settlers, including but not limited to Jewish refugees, moved to what had long been criollo land. Sinay focuses equally on the Moisesvillians’ immigrant struggle and on the settler-colonial conditions of their immigration. Just as importantly, he divides his attention, to the extent that surviving records permit, between the JCA settlers from whom he is descended and the criollo Argentines they displaced. He thus not only avoids a lachrymose telling of the Moisés Ville story, but frankly examines the ways in which the Jews of the Argentine pampas became actors within a colonial system of state repression.

The Jews who emigrated to Moisés Ville arrived toward the end of a major economic and cultural shift in Argentine society. In the 1860s, Argentina had become an agricultural powerhouse. English and Italian immigrants had set up farms and ranches across the plains. Their structured form of agriculture, which centered on the enclosure of vast tracts of land, was antithetical to—and, in the government’s eyes, more modern and lucrative than—the itinerant lifestyle of the region’s gauchos. Though today gauchos are central to Argentina’s national mythology, in the second half of the 19th century, the nation’s elites began to portray the cowboys as lazy and unruly, closer in spirit to the Indigenous peoples who had been chased out of Argentina than to the inhabitants of Buenos Aires and its surroundings. The state supported the new European ranchers and attempted to regulate the gaucho way of life out of existence: Gauchos could no longer travel or get paid without showing permits, and they were “forbidden from renouncing their patrons”—that is, from refusing to do casual labor for landowners. Any gaucho who sought to retain independence essentially became a fugitive.

Although gauchos were, by and large, criollos of Spanish descent—which means they were descendants of the land’s first colonizers—many allied themselves with Indigenous groups who’d survived state extermination. Others, Sinay writes, joined “bands of cruel thieves who appeared and disappeared like pirates on the Pampas, sewing terror through the fields now fenced and foreign, fields that had once been their own.” Some local authorities, perhaps out of quiet antagonism toward government regulation or perhaps simply seeking profit, tacitly sided with the gauchos who had turned to banditry. As a result, the Jews who emigrated en masse to Moisés Ville and its environs found themselves in the midst of entrenched, unpredictable violence.

Sinay positions himself as “heir to all of this” fraught history. He plainly wants to counteract the anti-gaucho sentiment that dominated rural Argentina when his great-grandfather arrived and is evident in his ancestor’s writings. Even Sinay’s language reflects these sympathies: Although the town’s Jewish immigrants came to Argentina after anti-gaucho regulation was well established, he positions them as part of the wave of settlers in whose favor the regulations were made by referring to them primarily as “colonists,” highlighting not their precarious status in the Old World but their connections to power in the New. Of course, these links were sometimes tenuous. Upon arriving in Argentina, the first Jewish colonists, who landed in Buenos Aires years before the JCA began buying up acreage, were defrauded in their first effort to purchase land and overcharged in the second. Once they reached the pampas, they suffered through a typhus epidemic and faced dire food shortages before Baron de Hirsch’s money reached them. Sinay describes this harsh period sensitively, but also emphasizes the plight of the gauchos whose traditional home the colonists, as well as many other European immigrants, now occupied.

In attempting to understand the Moisés Ville murders, Sinay finds that some are difficult or impossible to research, in part because “the criminals’ names don’t even appear” in either his great-grandfather’s work or his Spanish-language sources. It is “as if they didn’t matter,” he writes. “They are always just gauchos.” As he reconstructs both the colonists’ and the gauchos’ motives and lives as best he can, his commitment to telling a balanced, unprejudiced story shifts The Murders of Moisés Ville away from the sensationalism of true crime and toward the rigor of history. One of the lives he conjures with considerable complexity is that of Alberto Gerchunoff, the author of The Jewish Gauchos. As Sinay discovers, Gerchunoff himself was a victim of the conflict he tried to elide in his fiction: His father, Gershom Gerchunoff, was stabbed to death by a gaucho in 1891, most likely after the assailant made a botched attempt to propose to Gerchunoff’s sister. Gershom’s death is one of the 22 that Sinay investigates; the proposal-gone-wrong strikes him as a relatively simple, though tragic, case of culture clash exacerbated by linguistic misunderstanding. It is also a case in which Jews and criollos prove equally violent. Sinay discovers that, according to a local paper called La Unión, after the murder, many Jewish Moisésvillians joined together to “take justice for themselves and lynch the wretched man” who stabbed Gershom.

Yet extrajudicial killings appear nowhere in Alberto Gerchunoff’s depictions of rural Argentine Jewish life. Baffled by this omission, Sinay interviews Gerchunoff’s biographer, Mónica Szurmak, who sees The Jewish Gauchos as a retroactive effort to transform Moisés Ville into “an idyllic place.” Szurmak takes this transformation as a way for Gerchunoff to carry forward the optimism that led his father to emigrate. Gershom, according to his son, always “wanted to come to Argentina, a promised land where his children would be free.” By portraying Moisés Ville as an Eden, Gerchunoff retroactively fulfilled his father’s dream—at least in the eyes of Argentines who never set foot in Moisés Ville. Sinay persuasively connects this interpretation to Gerchunoff’s choice to write in Spanish rather than Yiddish in order to pursue a gentile readership; indeed, the literary critic Edna Aizenberg interprets The Jewish Gauchos as a thank you note to Argentina, understood as a “motherly refuge where hard-working immigrants . . . had found a bountiful homeland of meat and grain, if not milk and honey. It was a Jewish version of Latin America as utopia.”

It seems highly unlikely that anybody living in or near Moisés Ville in the years directly after its founding would have called it utopian. Poverty, hunger, and disease were rampant among the Jewish settlers. According to Mijl, so was fear, especially after a group of thieves murdered a family of Jewish shopkeepers—Joseph Waisman, his wife, and seven of his nine children—in 1987. They “robbed everything,” Mijl wrote, “and disappeared without a trace.” Sinay guesses that the thieves were motivated at least in part by need. Other murders also seem to spring from the gauchos’ dispossession, perhaps combined with their resentment of the government-backed takeover of their land—though in some cases Sinay cannot reconstruct a coherent motive at all. The murders of three Jewish brothers who left Moisés Ville to ask nearby Italian farmers for work and were later found dead in a stand of tall grass appear to be instances of random banditry. Other crimes, such as the town’s first killing—which took place in 1889, the year of its official founding—seem to stem from sheer miscommunication. In Sinay’s reconstruction, which is vivid enough to seem like a short story embedded in the book, a gaucho stumbles across the colonists’ bare-bones settlement, is struck by a Jewish woman’s beauty, and asks to marry her. Nobody understands his Spanish, but the Jews say, “Sí, señor,” then beg for food, which the gaucho brings. When the feast ends, he tries to leave with the woman he assumes is now his bride. She protests, and, in the chaos that ensues, both the gaucho and a colonist are killed. Sinay cannot verify this account, and after noticing how it overlaps with the story of Gershom Gerchunoff’s death, he starts wondering “how much confusion and how much truth is contained in each” tale.

In The Murders of Moisés Ville, the answers to these questions are often lost in a history biased against the pampas’ early inhabitants. Sinay never manages to identify the nameless gauchos in his grandfather’s text, though in some cases, he discovers that the killers weren’t gauchos at all. According to Mijl, a woman named María Alexanicer was brutally murdered during an “Indian raid” in 1906. In fact, no such raid ever occurred; María was shot by Moisés Ville’s police chief, Golpe Ramos—neither a Jew nor a gaucho—who had been courting her and may have raped her. Afterward, the Alexanicers covered for Golpe Ramos—thus, as Sinay points out, allying themselves with state power and joining the governing elites in their willingness to throw non-Europeans under the bus. Perhaps, Sinay reasons, the Jewish family feared that holding the police chief accountable would have jeopardized their ability to assimilate into Argentine society

Today, Moisés Ville’s Jews have, in many cases, integrated fully and happily into Argentine society, whether they have remained on the pampas or migrated to Buenos Aires and other cities in search of work. In modern-day Moisés Ville, Sinay hears plenty of Gerchunoff-style utopian stories about the JCA years—especially from non-Jewish Moisesvillians, who are now the town’s majority, yet take pride in their town’s Jewish legacy, as well as its history of interfaith harmony. Every year, Moisés Ville crowns a Queen of Cultural Integration; small though its Jewish population is, Yiddish can still be heard on its streets. Still, many of Moisés Ville’s remaining Jews acknowledge that significant cultural differences between criollos and other Argentines remain. According to Ingue Kanzepolsky, one of Sinay’s guides to the town, Jews may have “adopted the local criollo ways, but saying ‘Jewish gaucho’ is like saying ‘Jewish Bedouin’: there’s no such thing.”

After 1948, Sinay notes, many Jews “departed for Israel to live out the same colonizing ideal that their grandparents had known [in rural Argentina].” At no other point inThe Murders of Moisés Ville does Sinay draw a direct comparison between the state of Israel and Moisés Ville, though both are, of course, places where the JCA paid for Jews to settle land that was already inhabited. Still, it is difficult not to note that, as Argentina welcomed Jewish immigrants as a “civilizing force,” so England welcomed many of their onetime neighbors to Palestine—and so Israel has continued to welcome their descendants, while driving Palestinians out of their homeland and systemically discriminating against those who remain. Sinay doesn’t need to create a direct connection to this tragic present. It is more than enough that he refuses to flatten the Moisés Ville murders to fit a totalizing narrative of antisemitic violence in Argentina. In so doing, he not only rejects facile conceptions of Jewish victimhood, but also defies the Zionist idea that, by virtue of having suffered in one country, Jews are automatically entitled to land in another.

Lily Meyer is a writer, translator, critic, and PhD candidate at the University of Cincinnati.