Transitions in Jewish Time: A Trans Writer Visits the Mikveh

“Going to the mikveh meant giving my body, as it was, a place to be loved and called to holiness.”

TRANSGENDER BODIES are often stripped of our spirituality and mysticism. Ignored, reduced to a problem to be solved, or at worst rejected and violated, we’re often shunned or treated as strange and inaccessible in the context of Jewish communal life. For years, I’ve battled the internalized transphobia that insists trans people are inherently unable to make sound decisions about our own bodies. I felt I wasn’t trans enough because my relationship to surgery wasn’t purely linear, and I wasn’t spiritual enough, Jewish enough, to learn how to accept my body as it was and reconcile myself out of needing surgery.

But top surgery has felt necessary to me since before I had the words to describe it. As soon as the procedure date was set I found myself in my rabbi’s office, talking to her about my desire to visit the mikveh. I struggled to articulate why the ritual felt as necessary as the anesthesia or scalpel. We talked around it for a while before she leaned forward and asked, “What change are we marking in the mikveh?” She explained that we keep mezuzot on our doorposts to mark the transition from one space to another, physically and spiritually. We keep our holidays to mark transitions of time, hold b’nei mitzvot to mark our transition to adulthood. Articulating the transition, the before and after, is crucial to building the ritual. Judaism is a religion of marking transitions as both holy and wholly necessary.

The obvious answer to her question was that I was losing about four pounds of tissue in a carefully orchestrated and extremely expensive procedure that I’d been planning my life around for years. We both knew the traditional trans narrative: trans person is sad, trans person has a dangerous and tumultuous coming out, trans person has surgery, trans person is finally worthy of love and acceptance. Trans person is palatable; trans person is less likely to die at the end of the film. Trans Jew goes to the mikveh to mark the transition from incomplete to complete.

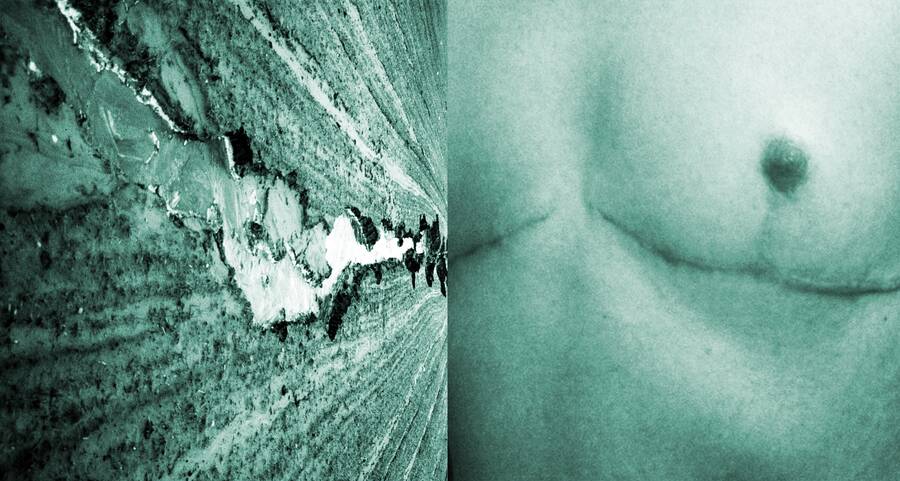

But that story was not, and continues not to be, mine. I’m sure it’s somebody’s story. I hope those people are doing well. I hope we both survive to the end of the film. Instead I’m a messy non-binary trans Jew cutting off their titties but still excited about sometimes wearing sundresses. I periodically get side-eyed in either bathroom. My hair is long and thick and curly and out of control, not shorn in that cute, tight butch cut all my transmasculine friends have. I would have to take my makeup off before stepping into the mikveh. I was not going from the bad kind of trans to the good kind of trans. I was going from the messy-hard-to-explain kind of trans, to a messy-hard-to-explain-with-thick-scars-spanning-the-length-of-my-rib-cage-in-both-directions kind of trans.

JEWS CONTINUE to invest in the mikveh because there’s something magical about the substance that makes life possible. Stepping into the waters means willingly lowering ourselves into the possibility for life within change, into the belief that the cliff before a river’s thousand-year erosion is equally as holy as its carved riverbed.

Going to the mikveh meant giving my body, as it was, a place to be loved and called to holiness. It said my body had always been good enough for kindness, and that this impending change, this shift in shape, was not because I was a broken, bent gear in need of sanding down. The water would have to touch every single part of my trans body to be a kosher immersion: what a fucking miracle for a body that’s been told it has no right to exist.

My rabbi’s question, “What change are we marking in the mikveh?” stayed with me for weeks before I found an answer. I was not marking the linear transition from one gender to another. I was not marking the transition from the wrong kind to the right kind of trans. I was marking my transition through Jewish time, and my right to stay within it. The mikveh created space to embrace the transition I was already experiencing; it held my trans body in a way that both the medical industrial complex and the secular world refuse to. It was less about marking a transition, and more about giving my transition a right to exist on its own terms.

WE DID NOT TELL the Orthodox family that runs the mikveh what we were there for. I paid $100 to be permitted the honor of existing in a liminal Jewish space—allowed in on the condition that I don’t tell my whole truth. My access existed somewhere between reverence for our sacred practices and acknowledgment of the deviance of my body.

I sobbed through most of the ritual. I had to really work to get the Hebrew of the prayers past my lips. Min hameitzar karati Yah, anani vamerchav Yah. Out of a narrow place, I called to God. God heard me fully and answered.

We sang the shehecheyanu and every part of my body touched the water. The power of being within that moment, singing holy words that recognize the beauty and magnitude of change, has not left me. It continues to compel me to stay within Jewish spaces, and to demand that my trans-ness is non-negotiable. I am not the first, and I will not be the last.

Our Jewish and queer seminal stories are ones of crossing over: survival and transformation in the face of despair and decimation. As queer and trans people, it’s revolutionary to continue living out our traditions. There is no way to unwind the braided existence of my gender deviance and my Jewishness. I went to the mikveh because I was called, by my ancestors and by a future where trans Jews define our own lives, bodies, and ritual practices. To descend into the waters is to be the cliff and the river that winds through it, expressions of a singular landscape, seemingly at odds but interdependent.

A note from the author: With love and appreciation to Rabbi Debra Rappaport, who supported my right to the mikveh and helped me get there.

Jayce Koester is a friendly trans Jewish witch living on occupied Dakota and Anishinaabe land (often called Minneapolis).