The Sharpness Comes Later

Multimedia artists Hadassa Goldvicht and Jacqueline Nicholls discuss self-censorship, labels like “Jewish” and “feminist” art, art as prayer, and more.

In this conversation, multimedia artists Hadassa Goldvicht (Israel) and Jacqueline Nicholls (UK) discuss self-censorship, labels like “Jewish” and “feminist” art, alternative ways of seeing, art as prayer, and more. This is the first installment in a series of dialogues between artists from the global Jewish network Asylum Arts (asylum-arts.org). The following excerpt has been edited for clarity.

Jacqueline Nicholls: When did you start calling yourself an artist?

Hadassa Goldvicht: I think I was trained to be an artist by my mother from a very young age. For my bat mitzvah, my mother made an exhibition of my work. That was my coming-of-age gift. I still can’t believe she did that. But then, today, when I have to say I’m an artist, the older I get, I am more embarrassed. It sounds like a fake job. It sounds privileged. Maybe it’s just in Jerusalem, where I feel like life is so much about survival. In my children’s kindergarten the past year, we are in June, and only now do I dare say to other parents what I do. Really in the last month, because I’m embarrassed.

JN: I understand that. Look, we’re not curing cancer here. Any kind of disaster situation at the art venue, it’s like, no one’s going to die from a mistimed lighting cue. But I think that trivializes what we do. I think we both think quite deeply and thoughtfully about life, and we wouldn’t spend quite so much time doing this if we didn’t really respect what it is that we do. So what do you think the role of art is within society? What’s its potential?

HG: I feel like art is a form of prayer; it creates change in the world on the same kind of frequency as prayer. There is this parallel world that affects our world in which art functions. I make my work with great fear because I feel like I do it as a form of very, very serious prayer. I very much believe it changes the world.

JN: I think I see it as not so spiritual. In terms of justifying myself as an artist, I’m horrified that my knee-jerk answer is I don’t know if I can do anything else. I don’t know if I can get a proper job. This is what I do. This is what I can do. The other day I went for a ridiculously long run, and I was finding it just really hard. I kept telling myself, but I can draw really well. I can draw really well. It’s a bizarre mantra: I’m good at drawing, therefore it’s okay to a bit rubbish at everything else. I know that’s a very flippant answer.

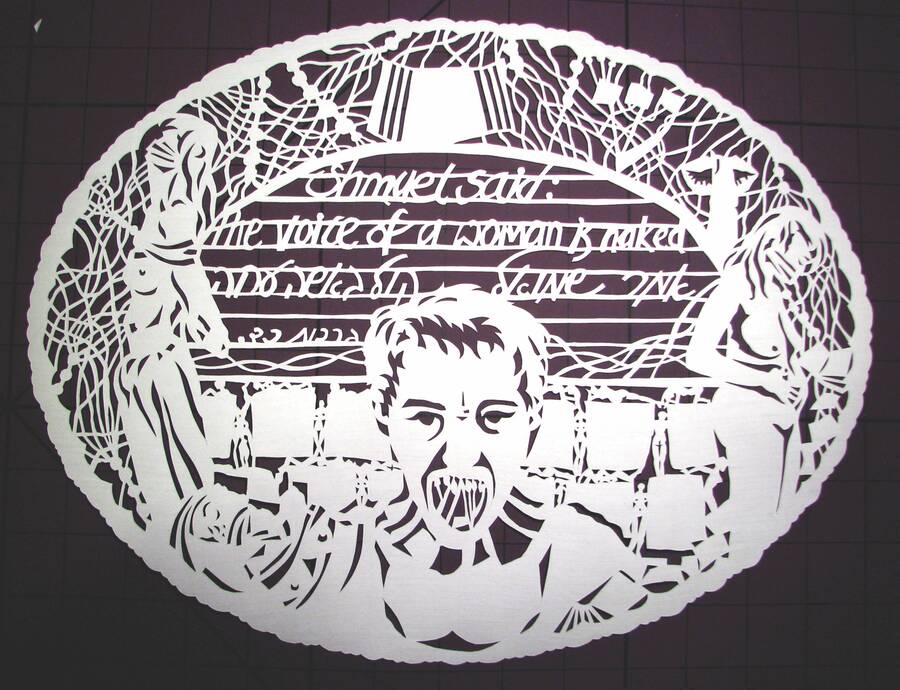

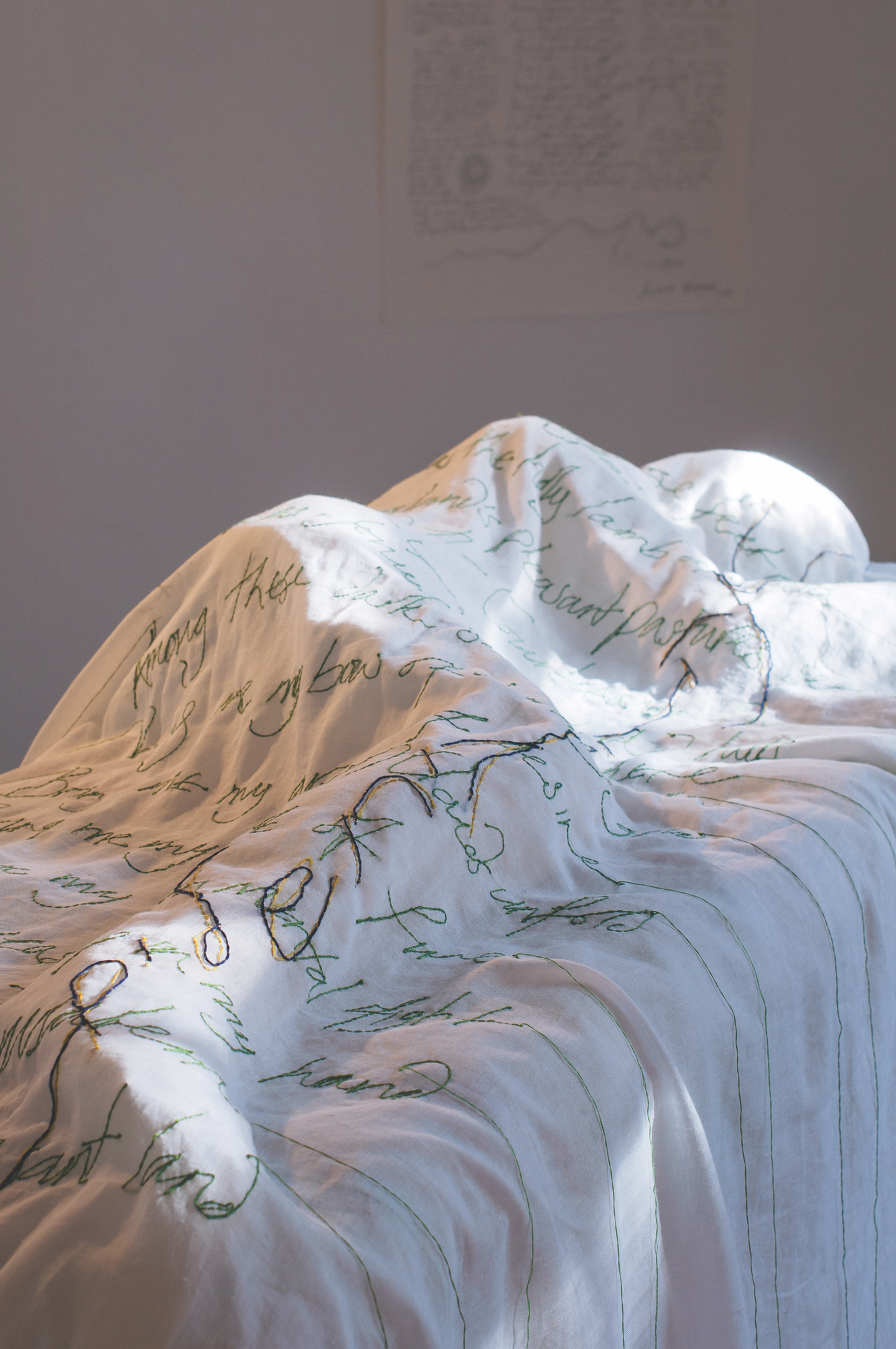

I do think art plays its part in fixing the world because it offers an alternative way of seeing. For me, what I try to do with my work is to create pieces that linger in the imagination, that have a strong image. I think that’s what changes minds more than a direct argument. The beauty draws you in and holds you. Then, you realize that actually there’s a very strong critique there. There’s something sharp, but the sharpness wasn’t the initial thing. The sharpness comes later.

HG: Do you feel like you might be marginalized by your work, by the fact that you make work within or in regards to the Jewish community? How do you feel about the terms “women’s art,” “Jewish art”? Are you okay with that?

JN: Part of me is fine with those labels because I am making work which is informed by my experience of the world. My experience of the world is as a woman; my world is a fairly Jewish world. I grew up in the orthodox community, I work within the Jewish world, I am married to a rabbi. Also, I don’t want to be a passive responder to Jewishness. I think it’s important to be a serious Jew, as in a serious, engaged Jew, and to not just blindly follow without being thoughtful about it. The way I think about things and the way I respond to that is through my work. That is my tool. I make work that is quite meticulous in its crafting, so I’ll be thinking as I’m making.

So I don’t mind those labels because it’s true, that is where I’m coming from. But I think it’s the confidence that I’m beginning to have now to say: but that doesn’t exclude my voice in wider conversations. It’s of interest to me what Muslim artists are doing with their heritage, with their baggage, especially Muslim feminist artists. I find their work so interesting. They’re asking very similar questions and I can see the connection. I think it’s about the confidence that we bring to these labels, that we don’t apologize for it. That I don’t go, I’m just a Jewish artist, you’re not really gonna be interested. I mean, I have been there. I have felt that. But I’m feeling increasingly, as I’ve gotten older: yes, this is me, this is where I’m coming from. And I am part of a wider society in London and in England and the world and all of that.

Having said that, I am very aware that when there’s a bunch of women who are sharing an exhibition, all the reviews will talk about women’s art and feminist art. When there’s a bunch of male artists who are showing work together, that’s art that’s normally about the human condition. These male artists are making work which they say is about the human condition, and I’m looking at it going, no, you’re making work about masculinity. That’s really interesting, but say it’s masculinity. Don’t assume it’s the human condition.

I actually want to take all those ways of possibly marginalizing me and say no, they’re going to open doors because that means I’m rooted in who I am, in my voice. Therefore, I can speak to others. I host a [Jewish] art salon, where we have artists who are not coming from a Jewish background, and they’re fascinated and they want to know more. They don’t think it’s parochial. Actually it’s about: do you open the books to open your mind and to allow bigger conversations? Or do you bring up Jewishness as a way of closing the door?

HG: I’ve always felt I make art about the human condition. So years ago I used to find it very disturbing when my work was defined within the context of woman’s art or Jewish art, though that doesn’t happen much anymore. Since I really do believe in this idea of art as a form of prayer, I really feel like all art is religious art or a religious ritual of some form. So when I’m asked where exactly I am on the spectrum of religion, I always keep it vague because I feel like it minimizes the conversation, and as someone who has a very private relationship to God, it feels like an invasion. On the other hand, I am and always was a raging feminist, and also a very Jewish raging feminist. That is just my human condition. My goddess, the artist Janine Antoni, once said to me something about how art needs to be extremely specific. When you talk about your mother, it needs to be the smell of your mother and the way her hand felt, it needs to be incredibly specific about one specific mother. Then, it opens up to be universal.

When I have an idea for work, I always do it; I don’t put restrictions on making the work. But I do have a lot of restrictions on showing the work. I don’t show some of my works within Jerusalem. I don’t put some of my work online. I censor myself in different ways. I think that surprises curators that work with me, finding out how much needs to be censored. Because my work is incredibly personal. It always involves either family members, or strangers that become very close, or myself. There’s always a lot of censorship in order to protect people’s lives or privacy, even spiritually, because I believe in art—that it changes the world in a way that’s sometimes scary for me. I censor sometimes because I’m literally afraid for my life.

The first video I ever made is a piece called “Writing Lesson 1,” referring to the Hasidic ceremony when a boy is three, where he is taken to school for the first time and asked to lick honey in the form of Hebrew letters, so his first experience of the language will be sweet. This piece of mine is the piece that I’m always asked to show the most and I probably refuse to show it the most for different reasons: because it’s a very private piece for me, but also because it was always written about in regards to Jewish feminism and how women didn’t get to do that ritual. So I’m doing that ritual as a woman and as an adult to “take it back.” I felt for years very uncomfortable with that reference because I felt like this piece is about my connection to the letters and how much I love the letters. [I am] intensely and sensually in love with the Hebrew alphabet. I actually think I have a weird form of synesthesia where I feel physically full from reading, even more than I do from food. It was so strange for me how it’s always given the feminist read, because it rendered invisible the most important part of the piece for me.

But then in recent years, I had to admit that I do believe our bodies are black boxes of political and social content, and when you ask someone a very personal question, it always contains all this social information. And my body actually does contain all the things that people read into that piece. And my body is one of a raging, orthodox feminist sometimes. Even though I hate, hate, hate each and every one of those words.

JN: I’m going to ask about the use of one’s body. Because I know in that video, it is you licking the letters. I have occasionally used my own body in my work, but not signaled it; when I do it, I don’t mean to do it as a self-portrait, like the fact that it’s my body is not relevant. But, maybe it actually is relevant how much of ourselves goes into the work, our female bodies. I mean, we’re both mothers and so we’ve both experienced our bodies grow and change. We also put ourselves bodily in our work. I don’t know if I have a question, actually. I just wanted to point that out. I don’t think we do it provocatively, but it just feels very natural. That, of course, our bodies would be in it. We’re not detached heads.

HG: I used to try to put different people in my work. Other people. And then, I realized that I’m using them in order to represent something. And I really can’t do that because every person is an individual. I wouldn’t want to use anyone’s body to represent something, the same way I don’t want my body to represent Judaism, or feminism, you know. It’s just me. So, I’ve been using my own body in my work. Just because it’s really the only thing I can say truthfully.

Hadassa Goldvicht is an artist living in Jerusalem. Her work has been exhibited widely including at the The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; The Jewish Museum, New York; The Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Venice, and The Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw. Photographs from her exhibition “The House of Life” are currently on view at Meislin Projects, NY.

Jacqueline Nicholls is a London-based visual artist and Jewish educator. In her ongoing drawing project, Draw Yomi, Jacqueline is drawing the Talmud, following the daf yomi schedule. She programs arts and culture events at JW3 London, and regularly teaches at the London School of Jewish Studies. Jacqueline’s art has been exhibited in solo and group shows in the UK, US and Israel. She was recently an artist-in-residence at Beit Venezia in Venice.