The Right to Grieve

To demand the freedom to mourn—not on the employer’s schedule, but in our own time—is to reject the cruel rhythms of the capitalist status quo.

In March 2022, a new species of mental distress was added to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a syndrome called “prolonged grief disorder.” Afflicted individuals find their everyday functioning inhibited by grief that persists for an apparently unreasonable duration following the loss of a loved one. Telltale signs include “feeling as though part of oneself has died,” a “marked sense of disbelief about the death,” and “intense loneliness.” How long is too long for such symptoms to linger? The American Psychiatric Association’s benchmark is a year for adults and six months for children. But the important thing is that “the person’s bereavement lasts longer than might be expected based on social, cultural, or religious norms.”

Though critics of the category of prolonged grief disorder—perhaps most vocally the scholar Joanne Cacciatore—have argued that the new diagnosis risks pathologizing the very act of mourning, the APA is not incorrect, exactly, to argue that “persistent grief is disabling.” But disability is not a natural or objective category; rather, it registers the way society is organized to accommodate some bodies and persons and not others. In particular, as scholar and activist Marta Russell has emphasized, disability is always defined in relation to work, describing those whose physical and mental capacities don’t fully conform to its needs, expectations, and demands.

The truth is that American society has made persistent grief disabling, because the demands that grief makes on a person are at odds with the way that American capitalism expects people to comport themselves as workers. The normal worker, in our economic system, is a person whose ability to work is not impaired by grief—not someone who doesn’t experience loss, which would of course be impossible, but someone who simply doesn’t let it get to them. There is no statutory entitlement to bereavement leave in the United States, except in the state of Oregon. In fact, Department of Labor guidance on the Fair Labor Standards Act explicitly cites mourning as the example par excellence of unprotected non-work: Federal law “does not require payment for time not worked, including attending a funeral.”

While the ideal worker under this regime is supposed to keep calm and carry on in the face of any loss, real workers experience grief all the time—in which case they must depend on the generosity of their bosses. Support is too often lacking. Gig workers, whose employers pretend to be nothing of the sort, are out of luck, as are the vast majority of part-time employees (which, of course, includes the millions of Americans who work full-time by stringing together multiple part-time jobs). Though upwards of 70% of full-time workers do have access to bereavement leave as part of their benefits package, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median allotment is a mere three days, after which employees—if they’re lucky—must start using sick days or vacation time. Employer policies also provoke painful conflicts over which relationships warrant time off to grieve. Often workers can only get dispensation to mourn members of their “immediate family” or that of their spouse. If employers grant leave after the death of an extended family member or a close friend, it is typically just a single day. Workers who have good relationships with their supervisors can sometimes circumvent such restrictions, but needing to prove one’s closeness to the deceased can be traumatizing or, for queer people in unsafe workplaces dealing with the loss of a partner or a member of their chosen family, even dangerous.

Grief unfolds at the scale of years, not days; half a working week is nowhere near enough time to process one loss, let alone the many that countless Americans have suffered.

Such conflicts have arisen more and more frequently in the past few years, as what epidemiologists term “excess mortality” has skyrocketed to unprecedented heights. Americans are currently confronting not one but two deadly epidemics: While Covid-19 has claimed over a million lives, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) reports that more than 100,000 people are also dying from drug overdoses every 12 months. And grief and loneliness are themselves major triggers of substance abuse. We seem to be trapped in an ever-escalating cycle of loss, despair, and death. Under these conditions, even the most generous of existing bereavement leave policies begins to look like a sick joke. Grief unfolds at the scale of years, not days; half a working week is nowhere near enough time to process one loss, let alone the many that countless Americans have suffered—or the unfathomable collective loss we have experienced as a society in the past few years.

In these circumstances, to demand the right to grieve—not on the employer’s schedule, but in whatever time one’s own act of mourning requires—is to reject a cruel status quo, and the expectation that we should accommodate ourselves to its deadly rhythms in the name of productivity. This is because the experience of grief is fundamentally at odds with the anthropology of capitalism, and with the mode of personhood it expects from its subjects. Grief is a threat to the peculiar way capitalism expects workers to relate to their time: as something objective, homogenous, and alienable; a commodity that can be signed over to an employer. Existing bereavement leave policy conforms to this understanding of time, returning a discrete number of hours to the employee to execute whatever tasks are thought to compose the process of mourning.

Grief doesn’t work that way. Its temporality is defiantly nonlinear. Like other forms of memory, as the philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin puts it in “On the Concept of History,” it “flashes up at a moment of danger.” In the wake of such eruptions, we move fluidly between the present, the past, and even the future—a future in which justice might be done to the memory of the dead. Fully inhabiting this alternative sense of time makes disciplined “work” in the capitalist sense impossible. One cannot attend wholly to the demands of remembrance while monitoring one’s email account from waking to sleep, or transmitting a ceaseless stream of coffee orders for hours on end.

Grief also splits the atom of the capitalist individual. The DSM is correct that a person who is bereaved feels “as though part of oneself has died,” but this isn’t a pathological symptom. It’s just the truth. Loss exposes the illusion of autonomous selfhood; just as a factory is brought to a standstill by a strike, we are made aware of our dependence on others by their disappearance. Again, the contemporary practice of bereavement leave attempts to bottle up this challenge, in this case by using the category of “family”—capitalism’s impoverished answer to the need for togetherness—to circumscribe who, or what, is mournable. Margaret Thatcher famously asserted that there was no such thing as “society,” conceding only that there were families as well as individuals—but grief gives the lie even to that tidy solution. Our need for one another and our love for one another will always exceed its contours. To politicize grief, then, is to challenge the tyranny of work in the name of collective care.

Grief splits the atom of the capitalist individual.

In the United States, the fight for the right to grieve has been prosecuted—haltingly, frustratingly—first and foremost by the labor movement. In the first half of the 20th century, access to paid leave, including bereavement leave, was almost exclusively confined to professional and managerial workers, one of the most glaring markers of the divide between the middle and working classes. As a result, securing paid leave protections became a major objective of the revitalized American union movement that found its footing during the Great Depression and codified its victories in postwar collective bargaining agreements. As an emergency board convened by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to monitor the threat of a rail strike observed in 1941, paid vacation was viewed as “a mark of social status and a recognition of the worth and dignity of the ordinary laboring man.”

But even though, by the early 1950s, paid leave was no longer the sole prerogative of the salaried elite, the struggle to expand access remained slow going, especially when it came to bereavement leave. When push came to shove, many postwar union leaders, especially following the purge of communist activists in the late ’40s, proved willing to prioritize improvements to wages and retirement and health care benefits over the fight for expanded freedom from work. On the whole, managers were more amenable to the idea that workers deserved pensions and health insurance in exchange for their hard work than that they deserved to be able to work less. Bereavement leave was further deprioritized within the sphere of paid leave bargaining. Workers expected to lose a loved one only a few times in their career, but they wanted to take a vacation every year, so it was vacation that took precedence if an employer decided to play hardball.

As a result, bereavement leave was an objective that most postwar unions reserved for their second or third contract fight—often unsuccessfully. Only an eighth of major collective bargaining agreements—the vast majority of which covered hourly workers in blue-collar jobs—guaranteed bereavement leave in 1953; by the close of the decade, the figure had risen to one-third. This tally, while an improvement, still paled in comparison to the approximately 85% of companies that provided paid bereavement leave to their white-collar, salaried employees. The gap continued to narrow in subsequent decades, but it has never been closed completely.

Postwar union contracts circumscribed bereavement leave provisions in other ways that persist to the present day, as unions made compromises in exchange for improvements to wages and benefits. The three-day limit was standardized in this period, although five days were sometimes allotted if it was necessary to travel to attend a funeral. Leave was almost always restricted to deaths in the “immediate family,” with a single day occasionally provided for “extended family” members. Contracts scrupulously delimited who was included in the “immediate family” category: typically, only an employee’s parents, children, siblings, and spouse, with allowances sometimes made for grandparents and in-laws. Friends were almost never included, although one contract signed in California in the late ’50s provided paid leave for a worker who was “acting as a pallbearer at [the] funeral of another employee.”

As such clauses suggest, employers negotiating over bereavement leave went out of their way to clarify that they were not conceding to a right to grieve, only a right to attend a funeral. The term “funeral leave” was used much more often than “bereavement leave,” and according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, workers were “frequently” required to provide “written evidence” that a funeral was actually held, and that they were indeed in attendance. Contracts typically provided no additional leave days if a funeral occurred on a holiday or during an already-scheduled vacation period. In one contract signed in 1961, the leave period was shortened to one day “for religious or similar observances held in lieu of a funeral,” even though many mourning rituals, such as the Jewish shiva, last for several days. There was something politically explosive about the idea that workers deserved to process their grief on their own terms; for unions still reeling from the purge of their most radical organizers during the postwar red scare, such a frontal assault on the employers’ view of the normative worker seemed altogether unfeasible. Instead, they acceded to the capitalist’s perspective, codifying the far more modest proposition that even wage workers deserved to discharge their social obligations—as long as they could do so in the span of a day.

The radical movements that emerged out of the cauldron of the ’60s challenged the limits of this postwar settlement. The wave of rank-and-file activism that swept through the labor movement in the late ’60s and early ’70s was motivated in part by frustration with the tendency of union leaders to focus on compensation at the expense of issues related to workplace democracy and the “quality of working life,” as it was known in industrial relations circles. The far left of the rank-and-file movement began to articulate an overtly “anti-work” politics, in dialogue with the “operaismo” current of contemporary Italian Marxism, which emphasized workers’ struggle against work itself as the engine of history under capitalism. For the activists who published Zerowork and other radical journals, the ultimate horizon of working-class politics was not fair pay for a fair day’s work, but the abolition of work altogether; they envisioned a reorganization of society that eschewed unnecessary labor and integrated what productive labor needed to be performed into the holistic rhythms of individual and collective life, rather than isolating and elevating it in a separate realm called “work.” Grief was one inescapable dimension of the properly human form of life that anti-work intellectuals and activists sought to create: communal rather than atomized; liberated from the productivity imperative; and saturated with collective memory. “It is as if a funeral is an opportunity for a festival where the living and the dead of many generations are all in it together, and memories are collectively reactivated,” the Italian communist economist Massimo De Angelis later reflected.

Most American union officials who actually sat at the bargaining table didn’t see matters this way. But as the ’60s wore on, they grew increasingly concerned with pacifying rank-and-file militants. New and expanded bereavement leave provisions were often among the results. The United Textile Workers of America signed a major contract in Virginia establishing bereavement leave in November 1966; that same month, the United Auto Workers (UAW) negotiated bereavement leave in a deal with an important aerospace employer. Between 1969 and 1973, the Oil Workers union repeatedly reopened the funeral leave clause in their deal with Atlantic Richfield, previously untouched since 1946, replacing the word “wife” with “spouse” to acknowledge the entry of women workers into the bargaining unit, and expanding the category of immediate family to include grandparents, siblings-in-law, and children’s spouses. The UAW won a similar expansion at Ford in 1973, securing leave after the loss of half-siblings as well as grandparents.

During this period, the phrase “bereavement leave” came into widespread usage, replacing the concept of “funeral leave,” and tracking a revolution in the understanding of grief and trauma in American culture. The proximate cause was the Vietnam War, which created millions of mourners, and gave rise to a new diagnostic category—“post-traumatic stress disorder”—designed in large part to capture the persistent sense of horror and loss that dogged many returning veterans.

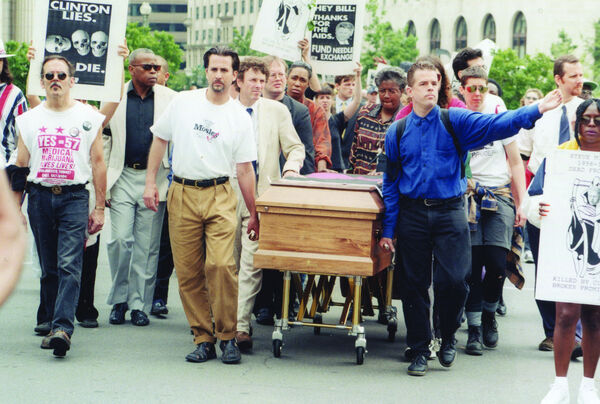

This linguistic and conceptual shift accelerated in the ’80s, as the HIV/AIDS epidemic set off another cascade of loss, and queer communities mounted the most powerful challenge to date to the restrictions on which loved ones workers are permitted to mourn. The heteronormative structure of bereavement leave provisions became increasingly intolerable to gay workers as the epidemic progressed. AIDS activists politicized their grief masterfully, attacking the callousness of the public health establishment and the homophobia of employers; ACT UP invented the “political funeral,” highly public protest-memorials conducted with the group’s trademark theatrical flair. Activists had the most success winning reforms in municipal public-sector workplaces, where gay workers were visible in the helping professions and in city arts bureaucracies—and where, by the late ’80s, unions were the strongest. In the summer of 1989, Mayor Ed Koch announced that he would issue an executive order allowing New York City employees to take bereavement leave after the death of a domestic partner, the first time the city had formally recognized such partnerships. That same year, San Francisco Supervisor Harry Britt—Harvey Milk’s successor—introduced legislation to extend spousal benefits (especially, according to the Associated Press, bereavement leave) to domestic partners of municipal employees; the legislation passed, was repealed by ballot initiative, and was finally reenacted by initiative in 1990. The Seattle City Council expanded bereavement leave for city employees to cover domestic partners in November 1989, and the Chicago City Council followed suit

in 1993.

The heteronormative structure of bereavement leave provisions became increasingly intolerable to gay workers as the AIDS epidemic progressed.

The gains of this period underscored that paid bereavement leave wasn’t just a convenience, but a ratification of workers’ basic personhood. It marked a concession to the dignity of gay partnerships that couldn’t be stuffed back into the closet. Apoplectic conservatives who suggested that the gay agenda wouldn’t stop at bereavement leave—among them New York mayoral candidate Rudy Giuliani—turned out to be right. Seattle extended health benefits to domestic partners of city employees a mere six months after enacting its bereavement leave reform. In New York, the same shift took almost a decade, but legislation that passed in June 1998 finally required the city to extend to domestic partners of municipal employees all the benefits it provided to spouses—as well as granting domestic partners the same authority as spouses in determining funeral arrangements, a long-running ACT UP demand. (The bill was signed into law on July 8th by none other than Mayor Rudy Giuliani.)

These gains for gay workers were one of the few bright spots for the American working class during an era that also witnessed the general decimation of the labor movement. As union density declined in the ’80s, company HR departments gained authority over worker leave policies that may once have been negotiated through collective bargaining. The true implications of this consolidation of employer power were not immediately evident: At first, benefits plans swelled in response to exploding health care costs, as well as to compensate workers for stagnating wages and metabolize their demands for quality-of-working-life improvements. Peripheral benefits like bereavement leave proliferated freely in this environment; the cost of three days of paid leave that most employees wouldn’t be eligible to use in any given fiscal year was negligible compared to the amount of money employers were devoting to health insurance plans. By 1992, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that 65% of full-time employees had access to paid bereavement leave.

But as the ’80s wore on, the conventional wisdom among employers turned swiftly and severely against the logic of benefits expansion, and indeed against the institution of full-time employment, with all its attendant prerogatives. With profits allegedly squeezed by unprecedented global competition, cost-cutting moved to the top of the agenda in boardrooms across the US, as employers took advantage of the increasingly fragmented, fissured, and unprotected workforce created by the anti-labor, deregulatory policy consensus of the Reagan and Clinton years. It was all too easy, in this environment, to regard grief as one more luxury that, according to the apostles of neoliberal austerity politics, neither employers nor governments could afford. (The US was far from the only place where this became the conventional wisdom. In fact, bereavement leave is one of the few areas where workers in other rich countries—including France, Canada, the United Kingdom, and other practitioners of a supposedly more humane welfare-state capitalism—receive, on the whole, just as bad a deal.) In 1993, the authors of the Family and Medical Leave Act deferred to the logic of austerity, passing up the US’s best opportunity to enact a statutory right to bereavement leave: The final version of the bill only mandated (unpaid) leave for employees who were caring for seriously ill family members—if the patient actually died, their caretaker needed to go back to work.

It was all too easy, in this anti-labor environment, to regard grief as one more luxury that, according to the apostles of neoliberal austerity politics, neither employers nor governments could afford.

Though the number of full-time employees with access to bereavement leave inched up 6% between the early ’90s and the early 2000s, the overall proportion of American workers who had such benefits budged considerably less, given that an increasing fraction of the workforce was employed part-time or in freelance or “gig” jobs. The crackdown on the right to grieve was most intense for the US’s most exploited workforce: its hundreds of thousands of incarcerated laborers. In the early-to-mid-’90s, states and counties all over the country revoked the ability of most inmates to leave prison to attend a funeral, citing the cost of the armed guards who escorted all but the lowest-security prisoners.

This logic of austerity ultimately confounded the efforts of a new wave of HR professionals and consultants to expand bereavement leave protections for corporate employees in the late ’90s, when the boomer generation’s parents began dying in increasing numbers. They succeeded in briefly making bereavement leave “a hot topic,” as The Wall Street Journal reported in 2000. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation sponsored an initiative called the Last Acts Workplace Task Force, which sought to gather data and raise awareness about the inadequacy of bereavement leave provisions in the US, and HR Magazine, one of the industry’s major trade journals, ran a feature in November 1999 on the need to “give time to grieve.”

But without the ability to threaten a strike, or a dramatic ACT UP–style protest, this more respectable brand of bereavement leave activism quickly ran aground. Rather than expanding access to paid leave, even for their white-collar staff, corporations at the turn of the millennium were more likely to introduce gimmicky “support” programs that fit with the era’s emphasis on team building and office friendliness. American Express announced that it would conduct a “workplace seminar on grief” whenever an employee at its New York headquarters died. Befitting its cloying reputation, Hallmark rolled out a program called “Compassionate Connections,” which matched newly bereaved employees with colleagues who had experienced a similar loss for peer-to-peer counseling—on their own time.

Today, bereavement leave advocacy remains dominated by HR professionals and HR logic. One of its standard-bearers is Lisa Murfield, an HR manager at the law firm Hill Ward Henderson who became convinced of the failure of employers’ existing approach to grief after she lost her son to suicide, but has ultimately been unable to transcend her profession’s instrumentalist approach to worker welfare. Her book, published in 2018, is called The ROI of Compassion, and it’s what it sounds like: a case for more supportive bereavement policy on the grounds that unprocessed grief is a productivity drain. “Organizations invite lower performance, production and profits by ignoring or not noticing employee pain,” Murfield explains. Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg has echoed this message since the death of her husband in 2015; in her book Option B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience, and Finding Joy, she reports that “grief-related losses in productivity” cost companies $75 billion annually. Invoking her own decision to double Facebook’s bereavement leave allotment, Sandberg writes that companies that adopt more compassionate leave policies “find that their long-term investment in employees pays off in a more loyal and productive workforce.” But even these visions of well-adjusted, trauma-free workers returning from bereavement leave to happily churn out surplus value have left most employers unmoved. As is often the case, the most ruthless capitalists see matters more clearly than their gentler functionaries: The concession that attending to “employee pain” ought to take precedence over work is a Pandora’s box not easily closed.

Two mourners comforting each other.

It is the task of today’s anti-capitalist activists to wedge that box wide open. The more militant labor movement that has arisen over the past few years has begun to train its sights on the inadequacy of existing bereavement leave provisions—a particular priority for the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America (UE) and the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), as reported by Julianne Tvedten for In These Times. Echoing the rhetoric that the labor movement has deployed to struggle for paid leave for nearly a century, UE General President Peter Knowlton argues that bereavement leave “is a basic sign of respect for workers and their families.”

Queer labor activists, meanwhile, have renewed the challenge to the restrictive definition of “family” still promulgated by most corporate policies. Several units affiliated with Washington–Baltimore NewsGuild Local 32035 have recently renegotiated bereavement leave clauses to substitute the language of “loved ones” for “family,” according to Sarah Coughlon, a union leader at the marketing firm M&R. Harry Young, a former member of the bargaining committee for a small nonprofit union in Massachusetts, was inspired to fight for improved bereavement leave after losing a loved one in the run-up to their union’s most recent contract fight. Ratified in April 2022, the new agreement allows employees to take bereavement leave after the death of a “person with whom they had a significant relationship.” “Some of us are queer, some of us are not in contact with our families . . . and we need protection for that,” Young told me. “If someone loses their best friend, they need time off.”

The labor movement should continue to fight for improved bereavement leave protections. Workers deserve whatever additional time off their unions can secure for them, and the challenge to the heteronormative limits of acceptable grief reverberates far outside the sphere of collective bargaining. But workers deserve more than that: They deserve a right to grieve. It might be helpful to understand this proposal as akin to the socialist feminist call for “wages for housework”—a deceptively simple demand that, when considered more carefully, lights up the limits of what the social structure of capitalism is able to tolerate. The slogan emerged out of the same Italian anti-work circles that helped inspire the labor radicals of the ’60s and ’70s. As developed by activists and intellectuals such as Selma James and Mariarosa Dalla Costa, “wages for housework” did not simply denote one policy proposal among others—some wonky tweak that might ameliorate the status quo—but rather a utopian horizon whose accomplishment would necessarily be revolutionary. The point was that capitalism was dependent in a structural sense on unwaged domestic labor traditionally performed by women. While wage workers had to pay for food, clothing, and shelter on the market, their wives and girlfriends cooked, sewed, and kept house for free. But every dollar that wives saved their husbands was a dollar their husbands’ bosses didn’t have to fork over in their paychecks. To fully redistribute this surplus value to the women whose unwaged domestic work made it possible would require the destruction of the existing capitalist power structure—and of the opposition between “real work” and “housework.” To call for “wages for housework” was, in reality, to call for an end to housework per se, as a devalued and gendered realm of labor cordoned off from the rest of our working lives.

To call for the right to grieve is not merely to urge the enactment of universal bereavement leave protections, but to demand, in a more fundamental sense, the abolition of an organization of labor that subordinates life and love to work.

In the same way, to call for the right to grieve is not merely to urge the enactment of universal bereavement leave protections, but to demand, in a more fundamental sense, the abolition of an organization of labor that subordinates life and love to work. The slogan illuminates the reality that, at present, the “right” to make many crucial decisions about how to weave mourning into the fabric of one’s life does not lie with workers but with their bosses. It’s a call to expropriate from the expropriators the authority to make what one will of one of the most existentially significant experiences a person can have. The right to grieve would entitle workers to rest, not merely a hiatus; but radical rest in this sense is impossible without the transformation of work from an imposition of capital to an expression of a person’s constructive abilities—one whose pace is governed only by the logic of that person’s needs, and of their community’s. Under such conditions, persistent grief would no longer be disabling in the sense captured by the DSM; the productive labor needed for human flourishing would no longer demand the existence of a normative worker free from vulnerability, loss, and memory.

As the political theorist Kathi Weeks has argued, “utopian demands” like wages for housework and the right to grieve have two functions, offering what she calls “perspective” and “provocation.” In supplying perspective, they illuminate something about our social reality that had hitherto escaped our notice, and in supplying provocation they challenge us to do something about it. Perspective is estrangement—the liberating awareness that it doesn’t have to be like this—and provocation, as Weeks observes, is hope. Utopian demands empower us not merely to reject the inevitability of the status quo, but to name our desire for something better than what we’ve been putting up with.

The mass death event we continue to live through has, of its own accord, provided many of us with perspective on the inhuman suppression of grief that is demanded of workers under capitalism—perspective we may dearly wish we had not been forced to acquire. But it’s here, whether we like it or not: the suddenly irrepressible awareness of everything we are shoving down to make it through the day, everything we’re trying not to remember, not to mourn, as we strain not to let our loss interfere with our productivity. The role of the right to grieve, then, is first and foremost to provide us with the hope without which perspective can swiftly become despair. Like that engendered by other utopian demands, it is a challenging but empowering hope. It calls on us to remain with our grief for a while, to follow its path ever outward: from loved ones to communities, to futures imagined and eclipsed, to ecologies vanishing in the advance of our intersecting environmental crises. The more capacious our appreciation of loss, the easier it will be to transcend a narrow psychotherapeutic understanding of mourning—one whose goal is to get us as quickly as possible back to work—and to instead appreciate its inextricable political and collective dimensions.

Sometimes I find myself distraught after reading the latest catastrophic news story—so many people dead from guns, from melting pavement and surging seas, from the pandemic that is supposed to have ended—and chastise myself for feeling so deeply a loss that, to all appearances, has nothing to do with me. But how are we supposed to fight for someone we don’t know if we don’t allow ourselves to mourn for someone we have never met? Socialism and grief have this in common: They require us to come to terms with the demands made on all of us by the suffering of others. “A socialist,” literary theorist Terry Eagleton has written, “is just someone who is unable to get over their astonishment that most people who have lived and died have spent lives of wretched, fruitless, unremitting toil.” May their memory be a blessing.

For Patrick Levine

Erik Baker is an American historian, an associate editor at The Drift, and a former UAW staff organizer.