ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL, who died on this day 48 years ago, was the greatest exemplar of the prophetic legacy of Jerusalem in the most anti-Jewish century of recorded time. He drew inspiration from the biblical prophets, whom he wrote about in great depth in his extraordinary 1962 book The Prophets, and strove to embody their immeasurably rich spirit; in a 1972 interview, he described these figures as combining “a very deep love, a very powerful dissent, a painful rebuke, with unwavering hope.” Heschel courageously enacted this love, dissent, and hope. And he painfully endured attacks from a fearful Jewish establishment and desperate Jewish people, who—fresh from the raw pain of the Holocaust and struggling to find a place in mainstream America—often opposed his radicalism. Writing in the immediate wake of the catastrophe, Heschel saw the stakes as being perilously high for his generation of Jews. He wrote in his 1951 essay “To Be a Jew: What Is It?”: “We are either the last, the dying, Jews or else we are those who will give new life to our tradition. Rarely in our history has so much been dependent upon one generation. We will either forfeit or enrich the legacy of the ages.”

Heschel’s vision had a profound impact on American Jews and other religious communities. But in our bleak times, his spiritual genius and prophetic witness are too often overlooked or ignored. Much as Heschel worried about his own time, today we are losing the capacity to take seriously holiness, loyalty, love, wisdom, prayer, and tradition. The far right is on the rise in the United States and abroad, and our market-driven culture, emaciated souls, and narcissistic selves have undercut any serious commitment or substantial allegiance to a quest for truth and justice. Though Heschel’s name remains widely revered, his ideas are rarely truly confronted, because of the challenge they pose to our moral complacency. As Heschel wrote of his own time in his 1944 essay “The Meaning of This War”:

Our world seems not unlike a pit of snakes . . . We had descended into it generations ago, and the snakes have sent their venom into the bloodstream of humanity, gradually paralyzing us, numbing nerve after nerve, dulling our minds, darkening our vision . . . In our everyday life we worshipped force, despised compassion, and obeyed no law but our unappeasable appetite. The vision of the sacred has all but died in the soul of man. And when greed, envy, and the reckless will to power, the serpents that were cherished in the bosom of our civilization, came to maturity, they broke out of their dens to fall upon the helpless nations . . .

Tanks and planes cannot redeem humanity. A man with a gun is like a beast without a gun. The killing of snakes will save us for the moment but not forever. The war will outlast the victory of arms if we fail to conquer the infamy of the soul: the indifference to crime, when committed against others. For evil is indivisible . . . The greatest task of our time is to take the souls of men out of the pit.

In his frank, courageous confrontation with the darkness at hand, Heschel recalls Paul Celan, the greatest poet to emerge from the dark ashes of Jew-hating Europe after the Second World War; his masterpiece “Death Fugue” poetically engages an evil that can never be mastered—only remembered. Just prior to Celan’s suicide, two years before Heschel’s own death, he wrestled with Heschel’s The Sabbath: Its Meaning for Modern Man, before concluding that the pit of snakes had saturated our souls beyond repair or redemption. These two Jewish geniuses constitute opposing poles in the progressive Jewish souls of our time, caught between Celan’s candid nihilism and Heschel’s unwavering hope. While Heschel appreciated the kind of deep existential wrestling that marks Celan’s work and life, he feared that the onward march of nihilism ultimately fans and fuels fascism. For Heschel, staring into the abyss must ultimately lead us not into despair, but toward one another. As he wrote in his 1965 essay “No Religion Is an Island,” we must “cooperate in trying to bring about a resurrection of sensitivity, a revival of conscience; to keep alive the divine sparks in our souls; to nurture openness to the spirit of the Psalms, reverence for the words of the prophets, and faithfulness to the Living God.”

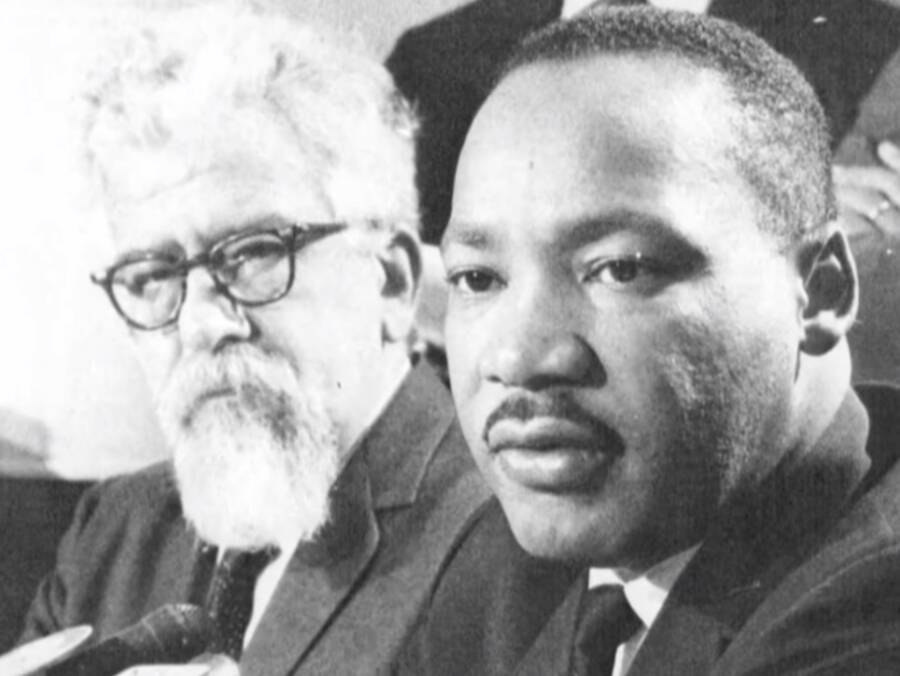

This view of the necessity of cooperation—of solidarity—led to his work with his close friend and fellow prophet Martin Luther King Jr. Though it is frequently acknowledged that Heschel joined King in the 1965 march from Selma to Birmingham—about which Heschel said the oft-quoted words, “our legs uttered songs . . . I felt my legs were praying”—the two are rarely understood as religious radicals whose projects were indivisible and intertwined. And they were: King’s critique of the US’s barbaric involvement in Vietnam is inconceivable without the strong and loving pressure of Heschel, while Heschel’s critique of American white supremacy is unthinkable without the words and deeds of King.

Today, as we face escalating hatred and greed here and in the Middle East, we cannot learn from the legacies of these two towering prophetic figures without also reckoning with their shared commitment to Zionism. It’s true that both King and Heschel died before the crystallization of the Israeli occupation of Palestinian people and lands, and prior to the scholarship and disclosures that have allowed us to fully understand how the foundation of Israel was built upon the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. And we know of King’s commitments to “fair and peaceful solutions” for Arabs and Israelis, as he wrote in 1967, and of Heschel’s concern for Palestinian lives. In his book Spiritual Radical: Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972, scholar Edward K. Kaplan records Heschel’s response to the 1948 Deir Yassin massacre, in which far-right Zionist paramilitaries murdered more than 100 Palestinians: “If Jews can do that, I’m so disturbed that I’m calling off the class,” Heschel said when he read about the massacre. Still, neither Heschel nor King fully appreciated the dispossession and violence of the founding of Israel as a settler-colonial state, nor foresaw its development into an apartheid-like system in the occupied Palestinian lands.

The fundamental question facing world Jewry—especially the younger generation—is how to keep alive the precious prophetic legacy of Jerusalem, exemplified in the words and works of Heschel and King, in the age of escalating neo-fascism. The answer to this burning question hangs on how we respond to Heschel’s call for remembrance, reverence, and resistance, asking ourselves: What and how do we remember, who do we revere, and why do we resist? What are the bounds of our sensitivity and empathy? In which narratives of the past and present do we situate, locate, and insert ourselves? Heschel—always open, as he wrote in “No Religion Is an Island,” to “confessing inadequacy,” and forever mindful of “the tragic insufficiency of human faith”—is an imperfect yet always inspiring model for asking these questions, as we endeavor to keep alive the prophetic flame, against the mean-spiritedness and cold-heartedness, the callousness and indifference of our Ice Age.

Let us forever remember his moral and spiritual greatness as noted in the unheard eulogy of his close friend, the minister and activist William Sloane Coffin in the words he handed to Heschel’s wife, Sylvia, at his funeral:

He was warm, wise, and he gently instructed me with his humor. It was always a joy to be with him. I loved him because he was the most biblical man I knew. He knew that reverence for God meant a certain irreverence for all institutions, including and particularly the State. Yet his judgments were always tempered with prophetic mercy.

Abraham Joshua Heschel died on the Sabbath with a kiss from God. Today his daughter, Susannah Heschel, carries on his unstoppable fire. Let part of his afterlife be such a flame in all our lives!

A previous version of this essay misstated the date of an interview between Abraham Joshua Heschel and Carl Stern.

Cornel West teaches at Union Theological Seminary. He is the editor of The Radical King.