The Heat of an Old Tale

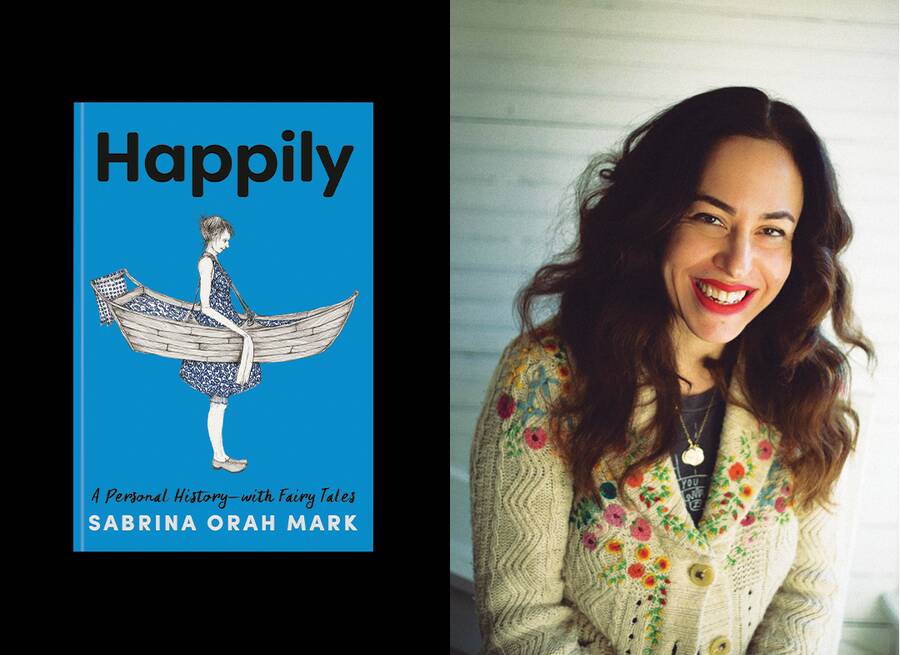

In her new book, Happily, Sabrina Orah Mark uses fairy tale forms to open the hidden doors of family life.

I first “met” Sabrina Orah Mark in correspondence when I invited her to write a story for a collection I was editing back in 2006. She kindly complied, sending me “My Brother Gary Made a Movie and This is What Happened,” a story based on “The Young Slave,” Giambattista Basile’s violent and disturbing 17th-century variant of “Snow White.” Mark’s retelling is lithe, comedic, and quirky—her stylistic signatures to date. That story was reprinted in her 2018 collection, Wild Milk, which is deeply influenced by fairy tales. Mark’s work has an elliptical, interior shape that magically welcomes the reader into what feels like a precious family fold. There nest familiar and fundamental questions, which call up the Old Testament tales that have populated Mark’s imagination since childhood.

In March, Mark published Happily, a collection drawn from her beloved Paris Review column of the same name, which used fairy tales to propel deeply personal explorations of motherhood, daughterhood, and marriage. Happily joins a too-slender shelf of autobiographical explorations of fairy tales, among them Cristina Campos’s essay collection Fairy Tale and Mystery, Eva Figes’s lyrical memoir Tales of Innocence and Experience, and my edited books Brothers and Beasts: An Anthology of Men on Fairy Tales and Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Women Writers Explore Their Favorite Fairy Tales. To this genre, Mark brings a voice that is sweetly querulous, open, and frank, even when the subject under exploration is heavy.

I spoke with Mark about her book of essays, the stories we both return to, and fairy tales as containers for what would otherwise overpower us. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Kate Bernheimer: Why haven’t we ever spoken before? Maybe I’m a recluse.

Sabrina Orah Mark: I also have hiding tendencies.

KB: I relate to so much of what you write about hiding in Happily—about the dangers of silence or sometimes the importance of it, the struggle of not wanting to hurt other people but feeling like you want to tell your story. I admire how you just jump right in and tell it.

SOM: I started as a poet. I’ve always had my stories, and I feel like I keep pulling a layer off of them. A lot of the stories in Happily are the stories in Wild Milk with the skin off. There was a moment when I was like, “I’m just gonna say the thing I’m not allowed to say.” Then I looked around—and everybody lived! And then I said the next thing and looked around; everybody lived.

KB: How does it feel for the book to be out?

SOM: There’s something so strange about a book being an object. I love it, and it also feels impossible.

KB: How can this thing that comes from an interior space now be outside? It’s like the opposite of eating an apple, which is just as improbable, an idea I borrow from the writer Kathryn Davis.

SOM: This reminds me that I love all your work on fairy tales and architecture—the book as building, the story as house, the body as fairy tale. It’s all this same kind of scaffolding.

KB: It gets at questions of What, anyway, is inside, and what is outside? I love how the scholar Maria Tatar calls fairy tales miniature domestic myths. I always think of the image of a tempest in a teapot.

SOM: I want to say: I am not a scholar of fairy tales. I largely came to them through the research I did for Happily, reading your work and Amy Bender’s work and Kelly Link’s work. The tales that I write about were not already lodged in my body. I went searching for them.

KB: But you did have a sense of magic from stories you encountered in childhood; you write about that in the context of religious tales. Those, too, are shared stories that have an oneiric quality. There are many different ways into expertise, which is another way of saying experience. And your experience of fairy tales probably began once upon a time when you fell in love with—well, you tell me. What did you fall in love with as a child? Hearing stories aloud? There is so much orality in Happily.

SOM: I think it was the idea of miracles and spells. It’s like prayer—this idea that by saying something, you might change the order of things. I come from a tradition where the story itself is understood as a mode of transformation.

KB: It strikes me that in Happily, the question is never just, Why do bad things happen to good people? or the reverse. It’s: Who is doing what and to whom? Who is eating, and who is being eaten? Who is devouring and who is being devoured? Who’s doing the mothering? Who’s not doing the mothering? Who’s doing the harm here—and where’s it going to end?

SOM: The impulse behind all the essays in Happily really grew from one particular question: How can I protect my kids? I felt that if I could see things in some particular way, if I could find a wisdom from somewhere far off, then maybe I could stitch that into some kind of garment my kids could wear. It was a way of trying to say: Yes this ever-shifting world feels endlessly on fire. But look at this beautiful flickering. There’s a new light I can see by.

KB: Extracting beauty from pain does not necessarily mean denying the parts that are terrible. That isn’t the perspective of Happily. It has respect for ambivalence.

SOM: For quite some time, my stepdaughter’s tarantula, Mavis, lived with us, and I wasn’t thrilled about it. I decided that I would start writing about her. And as I wrote, she started giving me lessons about stillness, about anger, about inhabiting two bodies at once. Toward the end of the book, I come home after being gone for a long time, and where there had been one Mavis, there are now two; she had molted. I was thinking about: Why do we choose certain paths? Why do we become one body rather than another? What does it mean that we shed these different skins throughout our lives? Mavis taught me that she could stand next to the skin that she had just shed, but if she touched it, it would hurt her because she was so vulnerable after molting. As I studied, I found lessons to lead me through a time that just was getting darker and darker.

KB: That’s part of what led me to fairy tales: They could contain all the things that were too overpowering in my day-to-day life. I could go to them, and without thinking about it—at least not consciously—I could study my world.

SOM: Do you have a favorite fairy tale?

KB: I often talk about David Bowie saying “I’m an artist and rock ‘n roll is my medium.” Fairy tales are my medium, so they’re all fair game. I do return again and again to the variations of “Little Red Riding Hood” from all over the world—the girl who gets distracted because she likes flowers. I love “Donkeyskin,” “Baba Yaga,” and “Hansel and Gretel.” But we don’t like to play favorites with fairy tales, do we? You say in the book that you don’t have one. Fairy tales can play favorites. They can have a favorite daughter or whatever. But not us. Still, are there any you especially return to?

SOM: I’m obsessed with Collodi’s Pinocchio. You can carve this thing, or you can write these words down, and these acts of your imagination can come alive—and then they’ll torture you for the rest of your life.

KB: You have a line in Happily that has haunted me: “Geppetto is the mother of all mothers.” Can you talk about that?

SOM: Geppetto for me is the present mother. The first thing Pinocchio does is kick him. And then Geppetto keeps running after him; he’ll go to the ends of the earth to find Pinocchio. Of course, at the end, it’s Pinocchio who saves Geppetto from the belly of the shark. That moment where he swims out with Geppetto on his back makes me cry.

KB: I always think of the Blue Fairy, who brings Pinocchio to life, as his mother—though she is absent for much of the story. But of course, Geppetto is the “present mother.” What a great turn of phrase.

SOM: And I love the language of that book. You’ve written about this: Often, the language of the fairy tale is flat—it’s a kind of container. But for Collodi, the language is exploding. I had written about this with regards to Bassile’s “The Flea,” but I think I took it out of the book.

KB: That’s the greatest moment, when you can’t quite remember what’s in your book. It’s a forgetting in order to remember again. You’re getting your book back in your imagination rather than as an object outside of you.

SOM: Does that happen to a lot of people?

KB: I hope so. We can do a study, though. Maybe it’s just fairy tale people who are like “What’s in my book?”

SOM: “Where am I?”

KB: “Am I very, very small? Or are these things around me very, very large?”

There’s a sense that a fairy tale is a technology, a structure. I think that you’re responding not just to the fact that we feel this, but also that we enjoy it—the way children enjoy putting little things into match boxes.

SOM: It’s like exploring an abandoned castle, opening up all the little doors inside of it. There is such a sense of setting, but often the place seems as though it could be an anywhere, or an everywhere; and at the same time, you know exactly how to get there in your mind. You might think: I know this because it’s a story from my childhood. It’s not that, though. I don’t even know if fairy tales are really for children.

KB: They certainly didn’t start out that way. As Maria Tatar said, quoting John Updike: “Fairy tales were the television and pornography of their day.” Of course, they weren’t only that, as her work explores. They housed secrets and warnings, testimonies and truth. But fairy tales are strongly associated with childhood in part because that’s where they have their safe harbor. They are preserved in the attic with other forgotten childhood objects until we take them out to play again.

SOM: There is something about a very old tale—how it is this thing that doesn’t go out inside of us. Last year, we had an electrical fire. The whole house was destroyed—but nothing got it as hard as the bookcase of fairy tales that I used to write Happily. When the fire inspector came, I was wandering around completely sleep-deprived; at the very end of his visit, I asked him to come upstairs. I was like, “That was a bookcase of fairytales. Do you think the fire—?” There were waterlogged and destroyed books everywhere—but there was a different energy in the destruction of the fairytales. The heat of the tales was so palpable in that space.

There is that feeling with the fairy tale: Let me embrace you while I destroy you and let me destroy you while I embrace you. There’s a misconception: People say, “This is not a fairy tale; this is real life.” But the fairy tale is way more brutal. I’ve written about loving the fairy tale because it brings members of the entire family—mother, brother, sister, father, grandmother—into their hottest state, and has them running from the house like it’s on fire.

KB: There is this terrible danger. But there is also this sort of catch-me-if-you-can quality. You make it out of the story alive.

Kate Bernheimer is an author of fiction, fairy-tale scholar, and World Fantasy Award-winning editor. Her most recent book is Fairy Tale Architecture, an interdisciplinary volume co-authored with her brother, Andrew Bernheimer.