Thank god your horrors outweigh your manners.

Justin Phillip Reed’s “Thank god your horrors outweigh your manners.” is part of a series of ekphrastic poems engaging Bill Gunn’s cult classic Ganja & Hess (1973). The film frustrated the white producers who had commissioned it, hoping to profit from a Black viewership by plainly rendering a horror movie with a Black cast. Instead, Gunn created an experimental work at the uneasy intersection of blaxploitation and horror. In Ganja & Hess, he draws together various predatory structures—including Africanist anthropology, vampirism, and classism—and ultimately exposes the very terms of representation under which the film was produced—the anti-Black exploitation that is profit—as itself a thing to fear.

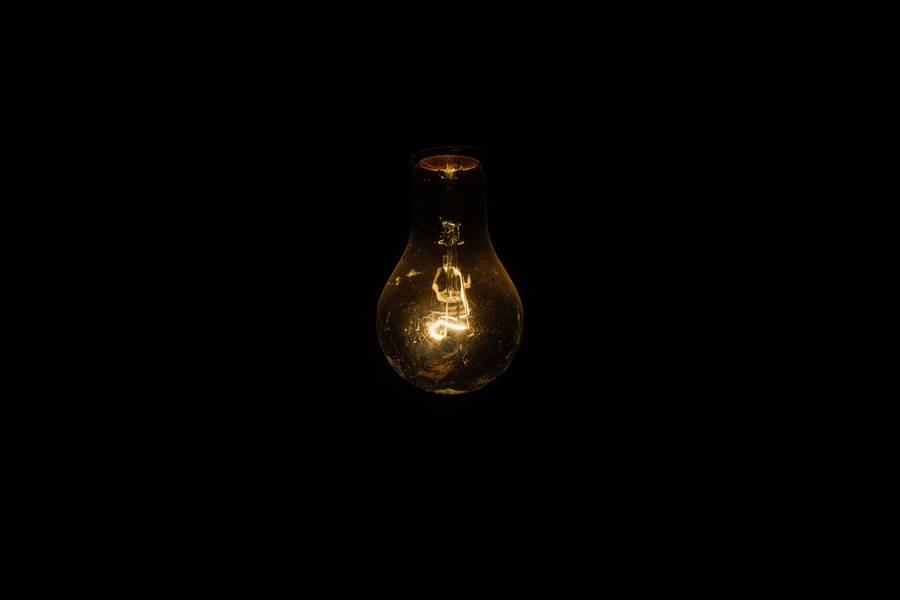

Like Gunn’s film, Reed’s poem makes a genre tell on itself. The poem opens in the negative space of a form withheld: “We are not permitted the image of his visage above an empty noose.” What is absent haunts the frame. Later in the poem, the noose recurs, opening out again, this time by way of simile’s cerebral logics: “The noose hangs like ego. Bulb of a man’s idea. Brief as the sun . . . You cannot adequately light a black thought.” Where the foundation of thought is itself a weapon of anti-Blackness, Reed suggests, dominant modes of representation can offer no out. When the poem concludes with the damning rupture of self-implication—“What conditions make possible this poetry?”—the question indicts not only authorship, but also readership, returning me to the incomplete image that opens the poem to confront my own implication in the image’s completion; absent the image, did I fill it in, following the old scripts?

– Claire Schwartz

Listen to Justin Phillip Reed read "Thank god your horrors outweigh your manners."

Thank god your horrors outweigh your manners.

We are not permitted the image of his visage above an empty noose.

I’ve mentioned to you previously the etiquette of lamps.

When the night is this heavy, you have to straddle it.

I am the only horse on the block. Trotting up to my house is a trick I was taught.

I’m proficient in the language of trespass. “My tree.” “My rope.”

I get to elope with empire, & use words like hope.

Deleuze remarks that such devices as the director’s self-decapitation in this frame suggest a “trans-spatial and spiritual whole . . . outside homogenous space and time.”

Together, in their twin outfits, the bisections of Hess & Meda make one suicide. It is nearly the getup that Jones’s Ben wore to his lynching at the end of Night of the Living Dead.

The noose hangs like ego. Bulb of a man’s idea. Brief as the sun.

But the mind is as wide as the night, which is the return of eternity.

You cannot adequately light a black thought.

Western philosophy is a byproduct of slave labor.

I am able to hear myself think either by way of rebellion or because one is being suppressed.

“I was a victim, on one hand, and on the other hand, I was a murderer.”

Thank God for horrors.

What conditions make possible this poetry?

Justin Phillip Reed is an American writer and amateur bass guitarist whose preoccupations include horror cinema, poetic form, morphological transgressions, and uses of the grotesque. He is the author of two poetry collections, The Malevolent Volume (2020) and Indecency (2018), both published by Coffee House Press.