German artist Gunter Demnig finishes installing a Stolperstein memorial in Madrid in April 2019.

Step by Step

Can Holocaust remembrance stones break Spain’s “Pact of Silence” around its civil war?

Growing up in Asturias, Spain, Silvia Ribelles knew her great-uncle José Antonio “Pepe” Montero was a war veteran. Her family didn’t discuss the details, but Pepe was missing a finger on his right hand and was deaf in one ear—injuries he sustained while fighting on the side of the fascist dictator Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War, and alongside the Nazis during the battle of Leningrad in World War II. Pepe was part of the Blue Division, the battalion of 47,000 Spanish volunteers who fought with the Third Reich, for which he was decorated with the German military’s Iron Cross.

Even after the end of Franco’s dictatorship in 1975, Pepe, who died in 2019 at the age of 105, proudly displayed his medals on the wall and attended yearly events honoring Francoist veterans. In the transition to democracy, “fascist” might have become a dirty word, but he still received a degree of official recognition. In Oviedo, the capital of Asturias, there is a monument to the Francoist defense of the city in 1936, in which Pepe participated, and until 2010, Blue Division Avenue ran across the city center.

Ribelles had another great-uncle, Luis Montero, who, like his younger brother Pepe, fought in the Civil War and in World War II. Luis, however, did not receive the same kind of recognition for his service. Ribelles only ever heard bits and pieces about this “black sheep of the family”—a Communist who fought with the Republicans, leftist defenders of Spain’s democracy, and later joined the French resistance against the Nazis. “They didn’t talk much about him,” Ribelles told me by phone from California, where she is a professor of Spanish at El Camino College near Los Angeles.

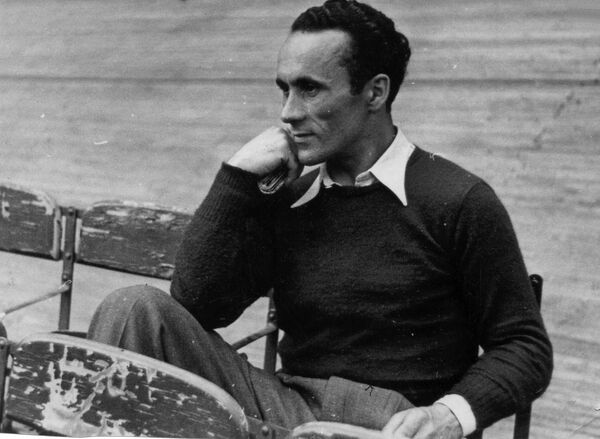

Luis Montero in 1947 at the Winter Velodrome in Paris during a Communist Party meeting. He mailed the photo to family in Spain. Photo courtesy of Silvia Ribelles.

It’s not that the family disowned Luis. Pepe used his fascist pedigree to help negotiate his brother’s release after Luis’s capture by the Franco regime in 1950, and the family mourned his loss after he disappeared that same year. But under the dictatorship, they could not discuss their Republican brother publicly, nor investigate what happened to him. This official censorship seeped into Spanish consciousness and lasted long after Franco’s death. “The Civil War is something that isn’t discussed in Spanish homes,” Ribelles told me.

It’s only in the past two decades that her generation, the grandchildren of those who experienced the Civil War, began talking about it. Ribelles, a historian, started digging into archives, and asking Pepe uncomfortable questions to unravel Luis’s story. She learned about how Luis was captured in France and deported to Mauthausen in Austria during World War II, part of a group known as the “deportados”—over 10,000 Republicans, mostly men, who were interned in Nazi concentration camps with Franco’s approval.

Ribelles, who detailed the facts of Montero’s story in a 2011 biography, had long thought about a small memorial for her great-uncle Luis. But she was put off by the ugliness of the political debate: Civil War memory in Spain has largely been suppressed and today manifests as a culture war between left and right, with memory battles spilling over into debates about the role of the church, LGBTQ rights, immigration, and regional separatist movements. Discussions of topics like bullfighting bans often devolve into opponents calling each other “facha” and “rojo”—fascists and reds—stinging insults referencing the conflict. She didn’t want to drag Luis’s name into a new political battle. Besides, getting even a small plaque for him in the center of Oviedo seemed unlikely. It was still controversial when in 2015 Oviedo removed a monument to Franco, and before that, in 2010, when the city changed the name of the avenue that honored the Blue Division. Almost anywhere in Spain, monuments to Republicans, especially militants like Luis Montero, are rare and divisive.

Almost anywhere in Spain, monuments to Republicans, especially militants like Luis Montero, are rare and divisive.

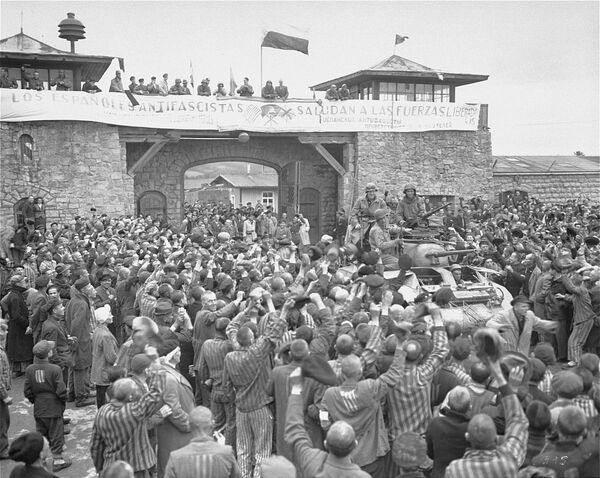

Luis Montero (center, left) on the day US soldiers liberated Mauthausen, May 5th, 1945. The prisoners had raided the concentration camp armory.

The Spanish Civil War was brutal; 200,000 civilians and prisoners were murdered. Historians agree that most of those killed off the battlefield were victims of Franco’s Nationalists, but more radical elements of the Republican opposition, including Communists, indiscriminately murdered landowners, industrialists, and thousands of priests and nuns. For his part, Montero remained a committed Stalinist militant even after the end of the Civil War. Following his liberation from Mauthausen in 1945, he led a group of guerrillas in the mountains of Asturias in the fight against the dictatorship. Many in Spain regard these guerrillas as “terrorists.”

But Ribelles, who says that her “centrist” politics don’t accord with her great-uncle’s, wanted to find a way to honor his memory. She sees him as a victim—tortured and exiled by the Franco regime, and thrust into World War II, where he would become a prisoner of the Nazis. Ribelles had read about Stolpersteine, or “stumbling stones”—the memorial plaques for Holocaust victims that have become ubiquitous in the streets and sidewalks of many European cities; she read that some had been recently installed for Republicans in other parts of Spain. Since 1992, the German artist Gunter Demnig has placed almost 100,000 four-inch-square brass cobblestones outside the homes or workplaces of victims of Nazism across the continent. The stones, intended to be “stumbled upon,” are everyday reminders of Nazi crimes and form the world’s largest decentralized monument. Most of the hand-engraved plaques are for Jews, but some are for Romanis, gay people, trade unionists, and other victims of Hitler. In 2019, Ribelles put in a request for a stone from Demnig’s organization and asked permission from Oviedo’s city hall to place it on the capital’s main street.

Ribelles “didn’t want it to be a political circus.” But, she said, “I was ready for a fight.” Even the most modest Republican monuments can trigger firestorms. In 2011, the Complutense University of Madrid installed a metallic column in honor of the International Brigades, the foreign volunteers who joined the fight against fascism in Spain. Conservatives demanded its removal, claiming the university did not have the required permits. It took six years of court battles and protests for the monument, which has been repeatedly vandalized, to be granted legal status.

Luis Montero Álvarez’s Stolperstein in Oviedo, Spain.

But Ribelles was pleasantly surprised to find no resistance to her request, and after paying 132 euros to the Stolpersteine Foundation in Berlin, she had her memorial installed: the first such stumbling stone in the province of Asturias. The golden block was embedded in the sidewalk outside the Oviedo train station in a small July 2021 ceremony attended only by family. In Spanish, it reads, “In the North Station worked Luis Montero Álvarez,” and beneath that, “Born 1908; Arrested November 30, 1942; Deported 1943 Mauthausen,” and finally, “Liberated.” “There was no negative press, and it hasn’t been vandalized,” Ribelles remarked, with some lingering surprise. What Ribelles stumbled upon is that while a Republican memorial is a political land mine, a Holocaust memorial is a welcome landmark.

What Ribelles stumbled upon is that while a Republican memorial is a political land mine, a Holocaust memorial is a welcome landmark.

Ribelles is not alone in discovering the story of the deportados. In the aftermath of a civil war that killed half a million, these relatively few have recently received outsize attention. There is the 2018 movie El fotógrafo de Mauthausen and the 2021 Netflix series Jaguar about Republican survivors hunting down Nazis in 1960s Madrid. Leftist leaders, like the 44-year-old founder of the Podemos Party Pablo Iglesias, have claimed the legacy of the deportados. They display the inverted red triangle, the symbol of Nazi political prisoners—pinning it to their lapels and appending the emoji to their Twitter profiles. The gesture identifies them as antifascists, and in turn affiliates their modern-day opponents with fascists.

This attention is significant: For 40 years, Spain observed a “Pact of Forgetting,” or Pacto del Olvido, an agreement between the left and right not to examine the crimes of the past, designed after Franco’s death to ease the transition into democracy. The pact was enshrined by the 1977 Immunity Law, which freed Franco’s political prisoners and allowed for exiles to return, while also forgiving all political crimes—an act that guaranteed impunity for Francoists who “disappeared” their enemies and subjected political prisoners to forced labor camps during the war and the dictatorship. The agreement meant there was no official recognition of Franco’s victims or opportunity for families to learn the fates of those disappeared. The country’s mass graves, holding the corpses of the tens of thousands killed mostly by Franco’s regime, lied untouched. In Spanish cities, street names honoring the dictatorship remained.

Unlike other formerly fascist European countries like Germany or Italy, Spain was not compelled by other world powers to undertake a reckoning with its crimes. Franco was not defeated—the almost 40-year dictatorship ended with his death by natural causes—and there was no equivalent of a Nuremberg trial or truth commission. Franco intended for the Spanish King Juan Carlos I to be his successor, but the young monarch instead used his power to shepherd in the democracy that Spanish society was yearning for. In a political tightrope act, the government reformed itself, without casting judgment on its past.

But in 2007, the Socialist Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, pressed by grassroots historical memory groups—passed the Historical Memory Law, initiating the country’s first official memory process. It mandated exhuming and identifying the bodies of victims of both sides, and initiated symbolic projects like the renaming of streets and removal of monuments honoring the dictatorship. In October 2022, another Socialist Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez, strengthened Zapatero’s legislation by passing the Democratic Memory Law, effectively banning all fascist symbols from public life and mandating a national DNA database to help search for the disappeared. It also officially recognizes the Spaniards who endured the Nazi concentration camps, opening the door for local governments to more easily dedicate public money to install Stolpersteine or other memorials to the deportados.

Few in the center-right Popular Party—the largest conservative movement—celebrate Franco, but the party has long resisted examining the past. It wasn’t until 2002 that it condemned Franco’s 1936 coup. Conservatives argued that Zapatero’s law violated the 1977 Immunity Law, long seen as the bedrock of Spain’s democracy and the stability needed for economic growth. The Popular Party threw up roadblocks to the memory process, resisting what they perceived as the left’s attempt to unilaterally rewrite Spanish history. When the party regained a majority in 2011, right-wing Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy eliminated the historical memory budget, paralyzing the efforts in progress. Today, a Socialist-led coalition rules on the national level, but conservatives in the opposition and in local governments continue to resist memory efforts. Meanwhile some far-right politicians increasingly defend the dictatorship’s legacy.

On a grassroots level, Spaniards have been placing Stolpersteine at a rapid rate since 2015. For some family members of deportados, like Ribelles, the stones have brought closure, a small way to honor their relatives amid Spain’s memory politics gridlock. Most stones, however, have been placed by left-leaning organizations and local governments with greater ambitions for Spain’s thwarted memory culture. Jesús Rodríguez and Isabel Martínez, a retired 68-year-old couple who run the Twitter account @iStolpersteine and are leading efforts to place stones in Madrid, believe there are over 800 stones scattered across Spain, many of which they have aided in placing. But an exact count is difficult; Spanish activists and localities are so anxious to place stones, they sometimes forge their own without Demnig’s permission.

There’s a palpable excitement among the activists, who see in the Stolpersteine an easier path to discussing the crimes of Franco. Esther Martínez Álvarez, a volunteer with the group Deportados Asturianos, told me that historical memory in Spain “came too little, too late,” but the 60-year-old sees “the Stolpersteine as a way of drawing attention.” She hopes the stones lead to larger memory projects for the deportados and other victims of Franco.

Memory activist Emilio Silva believes that conservative politicians agree to place stones like Montero’s because “in this case, the bad guys are not Spanish, the bad guys are the Nazis.”

But Emilio Silva, a prominent journalist and activist who is president of the Association of the Recovery of Historical Memory, thinks the plaques fail to advance Spanish historical memory. His organization has sponsored some stones, but he believes that conservative politicians agree to place stones like Montero’s because “in this case, the bad guys are not Spanish, the bad guys are the Nazis.” Spain, he explained, has long held a double standard for justice, applying it externally but not internally. “In October 1998, the Spanish justice system detained Pinochet in London,” Silva said, referring to the arrest of the Chilean fascist dictator, “but the same justice system is incapable of investigating crimes of the Franco dictatorship.”

Alejandro Baer, a professor of sociology and former director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota, believes the Stolpersteine are “a smart way to bypass the taboos, and the kind of censorship—even self-censorship—that exists in Spain.” But Baer, who grew up Jewish in Madrid, ultimately sees the Republican stones as a “detour” to the real historical memory work.

Indeed, the Stolpersteine may be sowing confusion—both as Holocaust memorials and as Civil War memorials. Several Spaniards I spoke to assumed they were for Jews, like the ones they had seen while traveling in cities like Berlin and Prague. But Spain has had a minuscule Jewish population since the Spanish Inquisition began in the 15th century. Only three of Spain’s stones honor Jews; the rest are for Spanish Republicans. For people like Ribelles, the fact that the context for the memorial is buried is part of the appeal. “That’s the beauty of this monument. It is apolitical,” she told me. “Even though this person was a Communist, they don’t put the word ‘Republicano’ in the memorial. They don’t put the words ‘guerra civil.’” In a country which has willfully forgotten the crimes of its dictatorship, the sudden remembrance of the deportados through Stolpersteine appears as a convenient half measure, acknowledging Republican victims, while obscuring who victimized them and why. “In order for a Republican victim to be remembered, that person needs to be revictimized—to be a victim of not one but two purportedly different historical phenomena,” the Spanish writer and cultural historian Juan Menchero told me. “The Republican victim needs to come across first as a victim of the Nazis, a paradigmatic victim of 20th-century violence.”

“Spain very often speaks about Germany’s memory culture as a model that we should follow here. But they are wrong,” Baer said on a Zoom call from Madrid. “They have not really understood what German memory culture is all about. It is a culture of acknowledgment of crimes.” In Spain, where there has never been a proper reckoning with the crimes of Franco, can these memorial stones serve their purpose? Or does routing Civil War memory through the Holocaust reinforce its erasure?

“That’s the beauty of this monument. It is apolitical,” Ribelles told me. “Even though this person was a Communist, they don’t put the word ‘Republicano’ in

the memorial. They don’t put the words ‘guerra civil.’”

In July 1936, Franco, supported by upper-class conservatives, the Catholic church, and landowners, led a military insurgency against the elected leftist government of Spain’s Second Republic. A loose coalition of liberals, trade unionists, Communists, and anarchists came to the defense of the sitting government. Even at the time, the Spanish Civil War was seen as the first battle in an incipient war against European fascism. Thousands of international volunteers flocked to Spain to join the fight, while Franco received the more significant help from Hitler’s and Mussolini’s militaries. Newsreels of the battles debuted the destructiveness of modern warfare that would define World War II, most notably the German air force’s bombardment of the Basque town of Guernica. The Spanish Civil War would also presage the mass violence against civilians to come.

Republicans forces battle street by street against Franco’s Nationalists near the Alcazar in Toledo, Spain, in 1936.

After almost three years of war, the Nationalists proved victorious. The end of the war, however, did not mean an end to violence. Franco shot 20,000 Republican supporters and held tens of thousands of others in concentration camps under horrid conditions throughout the 1940s. Half a million Republicans fled to France. There, they were confined to overcrowded refugee camps and the men were often coerced into hard labor, aiding the French military. During World War II, many of these exiles joined the resistance. Some, like Montero, were apprehended while fighting the Nazis; others were taken by the Gestapo directly from the French refugee camps and work groups.

Captured French, American, and British soldiers were held by the Germans in POW camps that respected the Geneva Conventions. But when the Nazis asked the Franco government what to do with the Spanish prisoners, it said it no longer recognized the Republicans as its citizens. With Madrid’s approval, these Spaniards were doomed to Nazi concentration camps, where a majority would perish. “Hitler did the dirty work of Franco, so the Spanish dictator could free himself of the citizens he considered too dangerous to return to Spain,” journalist Carlos Hernández de Miguel, author of The Last Spaniards of Mauthausen, explained to the Spanish newspaper El Diario.

Franco—whose press celebrated Kristallnacht and regularly spouted conspiracy theories blaming Spain’s problems on a Jewish Masonic plot—did not implement racial laws or deport Jews like his fascist allies. Still, Jews fleeing Vichy France were largely denied visas even to transit through Spain to Portugal, where they could take ships to America. Once Allied victory appeared likely in 1943, Franco took pains to distance himself from Hitler—whom he had supported with soldiers, workers, and supplies—while officially remaining neutral.

A banner that reads “The Spanish Antifascists Salute the Liberating Forces” hangs over the gate of the Mauthausen concentration camp. The photo is a reenactment of the liberation of Mauthausen, taken a day or two after the actual liberation.

After the war, Franco dictated the contours of Holocaust memory in Spain. To boost Spain’s international reputation, Spanish diplomats exaggerated the number of Jewish refugees who fled to or through the country, falsely casting Franco as a savior. Meanwhile, within Spain, information about Nazi crimes was tightly controlled. “Under Franco’s regime, it was possible to maintain this castizo [traditional Spanish Catholic] version of antisemitism, ignore the destruction of European Jewry and at the same time boast about having saved thousands or even millions of Jews during the Holocaust,” prominent Basque poet and essayist Jon Juaristi wrote in 2010. It wasn’t until 1979, a few years after Franco’s death, that Spanish state television aired the American series Holocaust and most Spaniards learned about the extermination of Jews. The association of Spain’s own concentration camp victims, Amical de Mauthausen, was illegal until the previous year.

The repression of Holocaust memory was part of Franco’s complete control of civil society. The authoritarian Nationalist Catholic regime banned independent political parties and trade unions, and censored all media. It prohibited the mourning of Republican victims and withheld reports on the deaths of those disappeared by Francoists. In Oviedo, a mass grave of over 1,300 Republicans sits outside the main cemetery. Until the waning years of the dictatorship, family members could only visit it clandestinely, throwing flowers over a thick wall while hiding their tears. Similar scenes played out across the country.

After Franco, the Pact of Forgetting, also called the Pact of Silence, reigned. And it wasn’t just a project of the right: It was agreed upon by both the Socialist and Communist parties, and maintained by the Socialist-led government from 1982 to 1996, under prominent dissident turned prime minister, Felipe González. Fear of sparking another civil war helped keep Spanish society silent. In 1981, armed far-right members of the national police stormed congress in a failed coup. Silva believes it sent a powerful message from the far right: “It said, ‘I’m still here, I’ll continue to be here, and if you try anything, I’ll return.’” “Growth” and “stability” were the bywords of this era, with party leaders focusing on the future, not the past. “Spain swept all of these crimes under the rug, and opted for forgetting and for economic development,” he explained.

It is only since the turn of the millennium that a growing “recovery of historical memory” movement—powered by a generational sea change—has begun to demand recognition of the crimes of the dictatorship. “The sons were very much scared to talk about it,” said Clara Ramírez Barat, Director of the Warren Educational Policies Program at the Auschwitz Institute, who did her PhD at the Universidad Carlos III of Madrid on the transition to democracy. “But the grandsons started asking questions and wanted to recover the memory of their grandparents.” Spanish society’s newfound interest in its own past coincided with the government’s introduction of Holocaust history into the national consciousness, aided by the European Union, which has encouraged its member states to commit to Holocaust education and commemoration as a show of democratic well-being.

As activists, writers, and historians made their case to Spanish society to deal with the nation’s past crimes, the sociologist Baer finds that the Holocaust was often used as a “bridging metaphor”; its status as a universally accepted paradigm of perpetrator and victim—or even good and evil—made it an attractive canvas on which memory activists could project Spanish history. The use of the term “Spanish Holocaust” to describe Francoist violence and concentration camps became more common. It is the title of Paul Preston’s acclaimed 2012 book on the violence of the Civil War and dictatorship, and is part of the title of a 2003 documentary by the journalist Montse Armengou about the early efforts to exhume bodies from the country’s mass graves. “I don’t hear anybody say that we should forget the Holocaust, that we should forget the death trains headed for Auschwitz or Mauthausen, that we need to forget Pinochet,” a Spanish woman named Clarisa, who had four family members disappeared by Francoists, says in Armengou’s film. “In Spain, however, a veil was drawn over the past, we had to forget our families, forget the suffering and the anguish.”

“I don’t hear anybody say that we should forget the Holocaust, that we should forget the death trains headed for Auschwitz or Mauthausen, that we need to forget Pinochet. In Spain, however, a veil was drawn over the past, we had to forget our families, forget the suffering and the anguish.”

An exhumed mass grave of people executed by Franco’s militia near the village of Lerma in Burgos, Spain.

Baer says that in this period, many activists, like Clarisa, began questioning why Holocaust memory was encouraged when there was no Civil War memory. Spanish conservatives in particular found themselves in a delicate position as they participated in the former, while avoiding the latter. Holocaust memory reflected poorly on Franco, an ally of Hitler, and elicited sympathy for the Republicans, victims of Nazism. The Spanish right sidestepped these inconvenient associations by adopting a definition of the Holocaust that focuses narrowly on its six million Jewish victims, and ignores other groups targeted by the Nazis like Republicans, the LGBTQ community, and Romanis—all groups that suffered under Franco and which continue to be marginalized by the Spanish right today.

Baer believes that highlighting the “singularity” of the Holocaust as a strictly German and Jewish affair permits the right to avoid a reckoning with the history of the dictatorship, and can even be used to rehabilitate Franco, making him look good by comparison. “It enables Spain to remember the Holocaust without questioning itself, without probing into its own past,” he wrote in the Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies in 2011.

A plaque commemorating Spanish Republicans murdered at Gusen, a subcamp of the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, sits at the site alongside the flag of the Amical de Mauthausen, an association representing the surviving deportados and their families.

Just as the right has sought to separate Franco from the Holocaust, the left has labored to emphasize the affiliation between the two regimes. “The memory movement has, as one of its rhetorical tactics, very effectively attempted to connect or to reconnect Francoism with Italian fascism and German Nazism,” said Sebastiaan Faber, professor of Hispanic studies at Oberlin College and author of Memory Battles of the Spanish Civil War. “It allows the memory movement to compare the way that Germany especially has dealt with its memory and victim rights with how Spain has not.”

The fact that this belated memory process is pursued by the left and obstructed by the right has turned memory into a partisan issue. Madrid’s current Popular Party mayor, José Luis Martínez-Almeida, began his term in 2019 by dismantling a partially constructed Republican monument at the site of a mass grave in the Our Lady of Almudena cemetery that had been placed by the previous progressive government, dismissing it as “sectarian,” “revanchist,” and “a complete and total rewrite of history.” In a place like Oviedo, where the local government has shifted between center-right and left-leaning political parties three times since the 2007 Historical Memory Law passed, this has left residents with a feeling of whiplash. Each new government has made over the city’s iconography: Street names connected to the dictatorship have changed back and forth, rainbow flags have gone up and down, and religious symbols have appeared and disappeared.

The fact that this belated memory process is pursued by the left and obstructed by the right has turned memory into a partisan issue.

Baer said he has seen an escalation in the right’s rhetoric. “It’s [no longer] that the conservatives are silent,” he said. “The right is now waging a cultural war of even vindication of Francoism.” Ramírez Barat of the Auschwitz Institute spoke to me about the troubling recent rise of Vox, a far-right political party that refuses to condemn Francoism and pursues an ultranationalist agenda—a state of affairs she connects to the inability to face history. “A democracy can’t be complete if people are unable to recognize the atrocities of the past,” she told me. Vox currently holds 52 of the 350 seats in parliament. “I didn’t think that was possible in Spain,” she said.

The Stolpersteine appear to bridge the widening chasm between right and left, allowing for public recognition of Republican victimhood, but without any reference to Spanish fascists. A superficial reading of the engraving suggests the crime happened over there—in Mauthausen or Buchenwald, not in Spain—thus satisfying the right. A deeper reflection inevitably implicates Spanish fascism, satisfying the left.

The deportados have a history of being a gateway for recognition of Republican victimhood. In 2000, Spanish government officials began participating in the Madrid Jewish community’s Holocaust memorial event, giving it official status. Unlike in other Jewish communities, Spanish Jews have long included other Nazi victim groups in their ceremony, like deportados and Romani victims. Top-level conservative statesmen who were otherwise content to remember Jewish victims of Hitler without examining Franco’s legacy were compelled through these ceremonies to acknowledge the deportados.

But according to Silva, this sanctioned form of Republican memory is little more than a bait and switch. In early March of this year, the same Madrid mayor who ordered the destruction of the memorial in the Our Lady of Almudena cemetery inaugurated a large sculpture in honor of the 449 Madrileños deported to Nazi concentration camps. It’s the capital’s second deportado memorial; the first was installed in 2019. Neither of the monuments recognize the victims as Republicans, but rather refer to them as “Spaniards” or “Madrileños.” Silva was angered by the demolition of a memorial that directly referenced the dictatorship. “They were building a monument for 3,000 people murdered by Franco after the end of the war,” Silva told me. “The mayor’s office destroyed it by hammer blows.”

The vice president of Amical de Mauthausen, Concha Díaz, and the mayor of Madrid, José Luis Martínez-Almeida, during the inauguration of a sculpture in Madrid’s Plaza del Rollo dedicated to the 449 Madrid citizens deported to Mauthausen during World War II, March 2nd, 2023.

The first Spanish Stolpersteine were laid in April 2015 in Navàs, a town of 6,000 in Catalunya. The region was a hotbed of antifascist resistance on the border with France; many Republicans found refuge there after their defeat. Stones for five deportados, three of whom were killed in Gusen, a subcamp of Mauthausen, were installed by Demnig in front of the town hall in a ceremony attended by relatives of the victims. In an email, the 75-year-old artist wrote that he at first hesitated to install the stones in Catalunya, since the Nazis did not deport anyone directly from Spain. “But without the German air force,” he wrote, “Franco would have stayed stuck in Morocco [unable to stage his coup].” The project also holds personal significance to Demnig, whose father was in the Condor Legion, the Nazi combat unit that fought in the Spanish Civil War. “What did he do there? I don’t know,” he wrote, “but for me, that’s the reason to do the Stolpersteine for Spain.”

To date, over 400 stones have been placed in Catalunya, where many of the deportados were from, with the support of left-leaning and separatist governments. Some members of separatist groups, whose goal is an independent Catalan country, have at times made their case with Holocaust analogies; in 2019, for example, a Catalan government official speaking at a tribute to the Spanish victims of Mauthausen implied a comparison between jailed separatist leaders and prisoners of the Nazi concentration camp.

Over time, the stones have mushroomed up even in cities with local governments that are hostile to memory projects. Rodríguez and Martínez of @iStolpersteine first attempted to place a stone in Madrid in 2015. They finally succeeded four years later, and have since placed 53 stones for Republicans in the nation’s capital, with 15 more in their home waiting to be placed. Oviedo got its first stone—for Luis Montero—in 2021. Rodríguez and Martínez lament that since Franco’s death there have been several failed attempts at remembering the victims of the dictatorship. In 2019, the couple was part of a group that organized a memorial at the site of the demolished Carabanchel prison in Madrid. Initially, the city’s left-leaning mayor dedicated funds for a memorial to the political prisoners held at the prison, which was notorious for torture during the dictatorship, but the far-right party Vox led an effort to block the funds. Rodríguez helped lead a community effort to research the names of hundreds of victims and fundraise for modest aluminum plaques. El País reported in December 2019 that these plaques disappeared within two days of being installed.

German artist Gunter Demnig poses with the families of deportados in front of a newly laid Madrid Stolperstein in 2019.

More ambitious projects like a Civil War museum, larger monuments, and the delicate work of exhuming mass graves demands funding and government cooperation that Spanish politicians have repeatedly failed to agree upon. By contrast, Rodríguez and Martínez wrote in an email, the Stolpersteine present a “fast and easy way to remember some Spanish Republicans” without inciting a backlash. They have helped individuals and groups install the stones across the country.

“People who are placing and requesting Stolpersteine have become fed up with waiting for something more comprehensive,” said Sara J. Brenneis, an Amherst College professor and author of a book called Spaniards in Mauthausen, who is currently working with activists on a digital map to help people locate and learn about Stolpersteine in Spain. And though some high-profile stones that foreground Civil War memory have been rejected—like the one for Francisco Largo Caballero, the Republican Prime Minister during the Civil War who was deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1943—it’s become rare for politicians to refuse stones outright. “I can’t imagine anyone not wanting a Stolperstein in their town,” Martínez Álvarez of Deportados Asturianos, told me in a crowded Oviedo café. “There’s no mayor, even the most right-wing one, who wouldn’t want one.”

Esther Martínez Álvarez, a volunteer with the group Los Deportados Asturianos, in Oviedo, Spain.

Martínez Álvarez is hopeful that the new Stolpersteine can become a potent educational tool to advance the memory process. Oviedo has dragged its feet in approving new stones, but Deportados Asturianos has succeeded in installing stones in other localities: Last year, the left-leaning city of Gijón sponsored 34. Since then, school groups have gone on walking tours, using the plaques to tell the larger stories of the Holocaust and the Spanish Civil War. Other towns and cities have similar walking tours and websites connecting the dots between Madrid and Mauthausen. “It’s very important that people understand that the Civil War didn’t end in 1939. The misery continued for many years and it didn’t end in Spain,” she said. Volunteers like her make enormous efforts to piece together what happened to each victim, uncovering stories that were often forgotten or never told because of the dictatorship. “One of the most satisfying things I have been able to do is to tell families what happened to their relatives,” Martínez Álvarez told me. “I met a woman who didn’t know her mother’s first husband was in the Holocaust. They always thought he disappeared in the Civil War.”

But despite these educational efforts, confusion around the stones—and the deportados—persists. By routing Civil War memory through Holocaust memory, the stories of the two victim groups have become conflated. The phrase “Never Again,” a term normally associated with the memory of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, is just as likely to grace memorials to Spaniards. In Gijón, for example, the “Nunca Más” sculpture, installed in the year 2000 in a park overlooking the sea, commemorates the “several hundred Asturians” who “died in the Nazi extermination camps.” The Gijón monument illustrates what Baer said is a common Spanish misrepresentation: Despite the use of words like “genocide” and “extermination” on the left to describe the Spanish experience during the Holocaust, Spanish Republicans, unlike Jews, were not sent to extermination camps and were not targeted for genocide. Brenneis agrees: “[Republicans] are victims of Nazi violence. They died, sometimes in the same circumstances as Jews, but there was no final solution against the Spaniards.” Even at Mauthausen, the Spanish inmates had little interaction with Jews, who were often gassed upon arrival. These misconceptions have made their way into pop culture: In the Spanish Netflix series Jaguar, Nazi physician Aribet Heim is said to have “tortured more than 300 Spaniards” at Mauthausen. In truth, Heim had around 300 victims in total; some were Spanish, but most were Jews. According to Baer, this conflation stems from an interpretation common on the left and with Catalan separatists in which “the Holocaust becomes fascism writ large,” a definition that encompasses all victims of European fascism, including victims of Franco.

Compelled by his own family history, Demnig embraces his concept being used to link the traumas of the Second World War and the Spanish Civil War. But he makes a visual and historical separation between the two: A sister project, called “Remembrance Stones,” uses stainless steel instead of brass when the subjects were victims of the dictatorship alone. In a more direct intervention into Civil War memory, the German artist installed 20 stones in Mallorca in 2018 in honor of politicians killed by the Spanish fascists. Written in the local dialect of Mallorquí, the stones list the date the politician was detained by Francoists, the prisons where they were held, if they were tortured, and the date and location of their murder. It is the only instance of the German artist honoring victims of violence apart from the Nazis. “The Remembrance Stones mark a turning point [in the project],” a statement on the Stolpersteine Foundation website explains. “Franco would not have ‘won’ without massive support from Nazi Germany, and this fact creates a bridge between two forms of memory stones.”

And yet, the work in Spain feels different than in Germany. In the latter country, the Stolpersteine are celebrated because they are mainly placed and cared for by the descendants of the perpetrators of the violence, like Demnig himself. In Spain, it is the families of the victims, or their political descendants, who are requesting the stones. When I brought this up to Martínez Álvarez, she said, “I’d love if someone who was not on the side of the victims, especially the Civil War victors, the Nationalists, or their children, recognized the victims. It would be stupendous.”

Baer says there needs to be a culture of acknowledgment for Spanish historical memory to advance. Most of the burden, he believes, falls on the right, but the left, he argues, also needs to acknowledge Republican atrocities. “I think that by now, we can’t just ignore the crimes committed by the Republican rearguard,” he told the national radio station Cadena Ser in February. “I think that we are sufficiently mature to discuss those crimes, condemn them, and that’s not going to make Francoism any less criminal.”

The question remains: Can the Stolpersteine lead to a deeper reflection on Spain’s past if they are silent on the political details?

Ribelles didn’t want Luis Montero’s stone to say “Communist” or “Republican.” Nor would she want it to say “Spanish Civil War.” She knows this is central to his tragedy, but she feels the current politics around historical memory would sully the memory of her great-uncle—who was, she ultimately concluded, murdered by his own party. She is one of the many Spaniards whom Ramírez Barat described to me as alienated by the memory battles. “We’re very satisfied with the stone,” Ribelles said. “It’s for a humanistic reason. We are all human beings that suffer. All these people suffered tremendously in the concentration camps, and we recognize that suffering.”

Brenneis thinks that too much time has passed to keep waiting for more direct memory projects. “It’s getting late for the generation of high school and college students who don’t know anything about this history,” she said. “It’s good to do something, even if you can’t do the overarching memory museum or the monument to victims of Franco.” She believes learning history is a “generative process,” and that honoring these few deportados will lead to a better understanding of both the Holocaust and the Civil War.

But Faber, the author and historian, stressed just how small of a step the stones represent. “If your goal is to satisfy a family who wants to commemorate their great-uncle, sure, that’s great,” he said. “But I think the memory movement as a whole has greater ambitions.” He said he’d like to see a change in the way the history is taught in schools and commemorated in public spaces. Ultimately, he said, it goes “beyond a tripping stone in the street. It’s the name of the street, and it’s the monument on the street. It’s the grand narrative of the collective memory of the nation.”

Andrew Silverstein is an award-winning writer based in New York. His work has appeared in The Forward, Slate, Grubstreet, and other publications.