Shall We Not Revenge?

In his polemic against Germany’s “Theater of Memory”—which relegates Jews to bit parts in the nation’s redemption narrative—poet Max Czollek may have traded one melodrama for another.

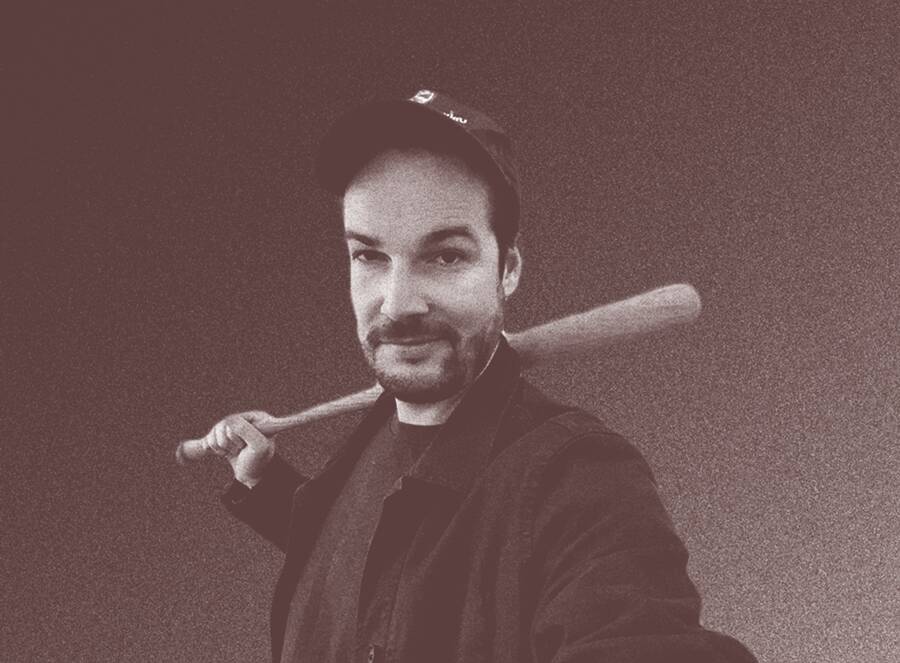

Max Czollek poses with a baseball bat in a reference to “the Bear Jew,” a character from Quentin Tarantino’s 2009 Nazi revenge film Inglourious Basterds.

Discussed in this essay: De-Integrate!: A Jewish Survival Guide for the 21st Century, by Max Czollek, translated by Jon Cho-Polizzi. Restless Books, 2023. 240 pages.

Last November at the Rü Bühne theater in Essen, Germany, Max Czollek, perhaps Germany’s most prominent young Jewish intellectual, read aloud a poem he had co-written after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The poem, “Golem im Zyklus” (“Golem in the Cycle”), draws on the myth of the golem, a creature created by Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague to protect the city’s Jewish community from a pogrom. In some retellings, the golem not only stops the initial attack but ultimately goes on a rampage himself, murdering Prague’s non-Jewish citizens. The poem closed with the consideration that “the golem was not crazy at all,” and had, rather, “more exactly understood his mandate / than his mandate maker himself.”

Such antagonistic visions preoccupy Czollek, a poet, playwright, and polemicist who has made his name assailing the restrictive roles Germany’s Holocaust memory culture has assigned living Jews. A Berliner since his birth in 1987, he arrived on the public stage in 2016 as co-organizer of an event called the De-Integration Congress, which challenged the ethic of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, or “overcoming the past”—the term most often used for Germany’s reckoning with its National Socialist crimes. While Germany’s engagement with its own historical atrocities has been internationally celebrated as a model of accountability, Czollek blames the country’s rigid engagement with the past for its present inability to deal with its diversity; the national redemption narrative, he argues, confines Jews and other minorities to performing roles that complement and flatter the rehabilitated German self-conception. He has elaborated on this subject in three books of polemic, three books of poetry, various plays and performances, and in Jalta, a journal and book series on contemporary Jewish issues that he co-founded.

As part of this project, Czollek and fellow poet Lütfiye Güzel—whose own work engages Germany’s treatment of its Turkish residents—have held readings across Germany for the past two years, billing themselves as “Inglourious Poets,” a cheeky reference to Quentin Tarantino’s 2009 Nazi revenge film, Inglourious Basterds, and its eponymous band of avengers. The copy for the Essen event promises poetic justice: “Even if literature may not be the most just revenge, it is, for sure, the most beautiful.” An Instagram flyer shows Czollek smiling wryly and holding a baseball bat over his shoulder, conjuring a character from the film nicknamed the “Bear Jew” who fells Nazis with skull-crushing swings. Czollek first used the phrase “Inglourious Poets” as the title for a 2015 essay that evolved into a chapter on revenge in his career-making 2018 polemic, Desintegriert euch!—now available in Jon Cho-Polizzi’s English translation as De-Integrate!: A Jewish Survival Guide for the 21st Century. The film also features prominently in Rache: Geschichte und Fantasie (Revenge: History and Fantasy), an exhibition at the Jewish Museum Frankfurt that Czollek co-curated last year.

In Czollek’s struggle for a self-directed Jewish identity, revenge has become his cri de coeur. “I’m writing this book because I have a problem,” Czollek proclaims about three-quarters of the way through De-Integrate!. “My problem is that my own conception of Jewishness began with an enormous pile of corpses. And for a long time, I was unable to think or write beyond this macabre mountain.” The gruesome image depicts Czollek as almost physically trapped in the role of “the Jew,” a German projection tethered to the coordinates of antisemitism, the Holocaust, and Israel. This Jew is the absolver of modern Germany—a would-be victim, gentle and passive, whose very existence points to the supposedly tolerant ethos of the refashioned state. Czollek’s self-styling as literary vigilante is an attempt to shatter this narrative and spur critical reflection on German identity: He positions literary revenge as a form of empowerment, a movement toward his goal of a kind of minority self-determination he calls “de-integration.” But does revenge, even as expressed through poetry, necessarily lead beyond cliché, toward a new self, or does it also insist on the predominance of the past, reinscribing it into the present without reconsidering its terms? Has Czollek found a way to see beyond the corpses or only—if by a novel maneuver—buried himself even deeper in his macabre mountain?

Czollek blames Germany’s rigid engagement with the past for its present inability to deal with its diversity.

De-Integrate! opens by challenging its presumed German audience’s expectations that the text will indulge in the melodrama of Jewish victimhood. “The book you hold in your hands is not a moving biographical account,” Czollek writes. “It’s not about the history of my family—about how a part of it was murdered—nor is it about the miraculous survival of my communist, Jewish grandfather.” It thus declares its intentions to withhold “biographical confession,” which Czollek later calls “the active capital of every minoritized individual.” Not quite an academic treatise nor a dramatic monologue—one German Jewish reviewer perhaps overenthusiastically suggested its provocations could be understood as “battle rap”—the impassioned, sometimes humorous text searches for a new set of scripts for German and Jewish identity while interrogating the prevailing drama’s underlying beliefs.

At the center of Czollek’s critique is what the Jewish sociologist Y. Michal Bodemann has described as a German “Theater of Memory.” For Bodemann, this theater stages memory as a performance of German and Jewish identity to affirm a Germany that has reconciled with Jews and overcome its Nazi past—enabling a return, Czollek notes, to “normal.” This performance of shared mourning—which largely manifests in national commemorations of the victims of Germany’s crimes—only concerns itself with living Jews insofar as their presence marks the difference between Nazi and present-day Germany. By nodding along with rhetoric that describes May 8th, 1945, as a day of German national liberation from Nazi rule rather than a day of defeat, and posting “Never Again” on International Holocaust Day, today’s “Good Germans” claim to adopt a Jewish perspective on the past, and thereby lay claim to contemporary redemption. Yet precisely by purporting to have “overcome the past,” Czollek argues, the Theater of Memory obscures the way the past bleeds into the present. Thus, rather than a guide to thinking about Jewishness in general, as its slightly grandiose subtitle suggests, Czollek’s text arrives on American shores as a warning about a memory culture that the United States has, perhaps, been too quick to hail.

Czollek shows how the Theater of Memory presages a second staging of national identity, the “Theater of Integration,” which constructs a German core against “Turks, asylum seekers, North Africans, Muslims, economic refugees, migrants, or Jews.” In the 2017 federal elections, the year before De-Integrate! was published in Germany, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) received 12.6% of the national vote, becoming the first far-right party to enter parliament since 1961. Czollek indicts Germany’s culture, which has enabled the ethnonationalism that drives the party, and confronts the set of fetishized terms that make up its ideological basis: Heimat, the fantasy of a homeland where blood belongs to soil; Leitkultur, a canonical “guiding culture”; and Integration, the assimilation of so-called Others into the German nation. In this “Theater of Integration,” Germany mobilizes its now-redeemed, now-tolerant culture to discern among its migrants who is good and deserves to stay—those who assimilate—and who is barbarous and must be expelled. Even more insidiously, it often presents its own Islamophobia as an attempt to protect Jews, whether by suggesting Islam is a threat to “Judeo-Christian” culture or framing pro-Palestinian speech as antisemitic—a ploy of politicians from across the political spectrum, who speak of “imported” antisemitism. Recognition of past problems is not enough to prevent their present repetition, with Muslims now replacing Jews as central objects of prejudice and exclusion.

Precisely by purporting to have “overcome the past,” Czollek argues, the German Theater of Memory obscures the way the past bleeds into the present.

Even as Czollek resists centering his experience, the text emerges from the circumstances of his life. As a student at one of Berlin’s first Jewish schools since the years of National Socialism, he was frequently approached by reporters who wanted to know if he felt “welcome” in Germany. These queries were inescapable reminders of his precarious position: a guest even in the city of his birth and a bellwether for the nation’s well-being. As an undergraduate in political science, Czollek encountered the work of Frantz Fanon and was inspired by the anticolonial philosopher to develop his thoughts about his relationship to Germany’s dominant culture through poetry. Later, while pursuing a doctorate on antisemitism, he worked out his own theory of “de-integration” in a series of provocative public performances: the 2016 De-Integration Congress, where he arranged for a banner to be hung along a major thoroughfare, laying claim to the Allies’ victory on behalf of Germany’s Jews—“WE WON!”—and the 2017 Radical Jewish Culture Days, which included among its events the opportunity to watch Nazis get beaten up on film while enjoying “Kaffee and Kuchen.” Today he stands as one of the most visible figures of a generation that has brought US-style identity politics—with its introduction of concepts like intersectionality and the white gaze—to the German literary-political scene.

Czollek’s critique of memory culture has caused such friction that even his right to speak as a Jew has come under attack. In 2021, the provocateur Maxim Biller, a right-leaning writer born to Russophone Jewish parents in Prague and later raised in Germany, told Czollek, who is patrilineally Jewish, that he needed to formally convert to be a Jew. Czollek reported the conversation to Twitter, demanding a discussion of “intra-Jewish discrimination.” Biller wrote a column about the exchange. Czollek responded with an interview. Newspapers ran explainers on the fracas; one Jewish correspondent called the back-and-forth a “circumcised cockfight.” Even the president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany weighed in, declaring that Czollek, “according to the laws of religion,” was not a Jew. The amount of attention paid to this kerfuffle only seems to confirm Czollek’s argument about the centrality of Jewishness to contemporary Germany—and the corresponding lack of space for intra-Jewish diversity, which Czollek suggests has to do with the very fragility of Jewish identity in Germany.

Against this dominant Theater of Memory, De-Integrate! gestures toward new performances that strike back against the regulating German perspective. One instance he cites is the 1985 storming of the stage at Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Der Müll, die Stadt und der Tod (Garbage, the City, and Death), which featured an antisemitic portrayal of a wealthy Jewish speculator. While a thousand people protested outside, “thirty, mostly elderly members of the Jewish Community in Frankfurt” took the stage instead of the actors: “Suddenly living Jewish people [were] demanding their right to political participation while a German audience had only been able to imagine them” as stereotypes. And yet, as the 1985 action shows, de-integration always plays out in front of the German audience; Czollek is aware he cannot escape performing in that theater, which he calls playing “a Jew for Germans.” “A book like this,” he writes, “also reproduces the process by which human beings are reduced into representatives of Jewishness for public consumption.”

Caught in this bind, Czollek chooses to ditch the role of the “Good Victim” and instead play an “Inglourious Poet,” a Jewish avenger. Commenting on Shylock’s famous lines from The Merchant of Venice, “If you wrong us, shall we not revenge?” Czollek writes,

Honestly: “Wrong us” seems like quite a euphemism when you re-read these lines in the context of the 20th century and the attempted murder of all European Jews. I mean, doesn’t all of that just kind of justify and legitimize a Jewish desire for revenge?

In the same chapter of De-Integrate!, “Inglourious Poets: Revenge as Self-Empowerment,” Czollek assembles what he calls “an archive of resistance” against “the model of the peaceful, defenseless Jewish victim.” He argues that exploring “revenge art”—he champions Inglourious Basterds as “one of the pivotal works” of the genre—is “one way of processing these internalized clichés,” a “prerequisite for an effective critique of the Theater of Memory.”

Czollek’s exhibition at the Jewish Museum Frankfurt invited viewers into a multivocal exploration of Jewish revenge. While its subjects ranged from vengeful passages from Haggadot to Jewish pirates and gangsters to comic book figures, Holocaust history stood at its core. It presented the life and writings of resistance fighters like Zipora Birman, who fought to her death in the Bialystok Ghetto Rebellion of 1943, and Herschel Grynzpan, who murdered the Nazi diplomat Ernst vom Rath in 1938 in retribution for his family’s deportation to Poland and the worsening political condition of Jews in Europe. It told the story of Nakam, an organization founded by Israeli poet Abba Kovner, that aimed to kill the same number of Germans as Jews killed during the Holocaust, including through a 1945 plot to poison Nuremberg’s water supply. It also returned to the myth of the golem and other revenge tales from the Jewish canon—like the story of the biblical Samson, who pulled the Philistines’ temple down upon his enemies and himself in a moment joining vengeance and suicide.

Yet despite the potential of revenge to end in tragedy, the exhibition insisted on the concept’s liberatory potential. “The absence of justice continues to resonate,” explains the exhibition’s curatorial text, with reference to the Shoah, “but it also inspires the imagination.” This inspiration arrives, once again, via Inglourious Basterds. Tarantino’s film, which begins with Nazis massacring a Jewish family and ends with the family’s lone survivor burning the entire Nazi high command alive in her movie theater, was the subject of the opening and closing installations. The Bear Jew’s prop baseball bat, dramatically lit by strobe light, welcomed visitors, and a three-channel video piece by Daniel Laufer, which re-creates scenes from the film with young Jewish artists acting as the avengers, sent them off. Were they actually making something new out of Tarantino’s film, I wondered as I left, or did the film’s projection of a certain kind of Jewish strength belie its own narrative exhaustion?

Czollek might pose with a baseball bat for photos, but his identification with the Bear Jew only goes so far; he does not take revenge with his bat but rather with his pen. He outlines his strategy for poetic justice in a chapter of De-Integrate! called “Ahasver’s Hell: Or, Things Will Never Be ‘All Good’ Again,” which reworks the archetypal antisemitic myth of the Wandering Jew, a New Testament figure condemned to roam until the Second Coming. For this plank of his de-integration program, Czollek draws explicit inspiration from his childhood dreams:

I dreamed of killing Hitler, Goebbels, and their whole concentration camp team. I never fantasized about making everything “all good” again. I dreamed about fighting back. Hitting harder. If I couldn’t stop what had happened, I at least wanted my revenge.

Revenge art, he notes, helped him channel his anger into poetry; in this medium, “different forms of justice can be realized than those that exist in our daily lives.” In his poem cycle A.H.A.S.V.E.R., Czollek carries out this revenge by trading the wandering Jew for an antisemite who appears in the guises of Joseph Stalin and Joseph Goebbels—and denies him any future possibility of salvation. By “condemning them to literary Hell,” Czollek writes in “Ahasver’s Hell,” he has gotten “my kind of revenge.” As he put it in an early version of De-Integrate!, a 2017 manifesto published in the first issue of Jalta, “our revenge ensures that the perpetrator society cannot find peace.”

However, this focus on the perpetrator threatens Czollek with a kind of imaginative myopia. Take the instance of Abba Kovner, a central figure in his “Inglourious Poets” chapter as well as the Jewish Museum exhibition. Czollek sees a fitting justice in Kovner’s taking on the medieval antisemitic trope of the well-poisoner in his search for justice after the Shoah: “Not such a bad comeback,” he quips. But is this clever inversion all that Czollek’s vision of de-integration has to offer? While the introduction of Kovner’s story into greater circulation may indeed broaden the Jewish imagination, Czollek’s fixation on revenge may have the opposite effect. After all, Kovner’s desire to inflict like for like on the perpetrators seems rather to resolve into an impossible quest for equivalence with the initial injury, highlighting the threat of revenge to impoverish imagination.

Perhaps nowhere are the limits of this imagination captured more clearly than in Czollek’s ongoing identification with the Bear Jew. For all its campiness, the image of Czollek posing with the bat still affirms the ideology of the Muskeljude, or “Muscle Jew,” the Zionist ideal of masculinity popularized by Max Nordau and Theodor Herzl—a kind of internalized antisemitism that saw the supposedly gentler masculinities of the diaspora as a degenerative sickness. Substituting Jewish strength for Jewish victimhood is seductive, but Czollek’s rejection of the Good Victim does not obligate him to put on the costume of the strongman.

Indeed, taking up the bat hardly breaks the bonds tying Jew to German in the Theater of Memory; it threatens, instead, to reinscribe the avenger’s dependence on the perpetrator. To valorize the revenge plot risks simply reversing the action of the victim plot to which Germany’s Jews have been subjected, replacing one melodrama with another rather than altering the underlying logic. In classic sentimental narratives like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, evil victimizes good; the audience is meant to be moved by this suffering and respond by resolving the wrong as it manifests in their own lives. In Czollek’s preferred revenge tales, the good survives victimization and, without relying on outside intervention, strikes back on its own. This is the story of most action films—and indeed the logic of Inglourious Basterds. Yet in both, it is the villain who acts first, who initiates the plot with his villainy, and thus creates the frame for the story. To take up the character of the avenger is not to engage the past from a newly powerful position, I fear, but rather to give the past even more weight to determine the present. What would it mean, instead, to resist both forms of melodrama, play neither victim nor avenger? As Czollek notes, in Germany it might be impossible to exit the Theater of Memory altogether. But couldn’t we instead attempt to stage stories of Jewish life not framed, first and foremost, by a relationship to suffering?

To take up the character of the avenger is not to engage the past from a newly powerful position, but rather to give the past even more weight to determine the present.

Czollek may insist that things will never be “‘all good’ again,” but he also indicates his desire to think beyond opposition. Though De-Integrate! largely remains within the binary of the Theater of Memory, opposing German to Jew, it ends by making an unexpected tonal shift, insisting on the need “to move away from identitarian ideals of belonging to one, particular group: away from the idea that our identities are something whole and self-defining, and that we must fight to defend their integrity.” In his chapter on “revenge as self-empowerment,” Czollek indicates that he sees the revenge paradigm as a means of courting this deconstruction of Jewish identity; he insists that “when we surrender the position of the Good Victim, the Jewish subject is revealed as fragmentary, inscrutable, and unstable.” And yet, repeatedly taking hold of the baseball bat does a disservice to his own thought, leaning on markers of identity rather than wrestling with the nuances and contradictions involved in de-integration. If Czollek wishes to create more space in Germany for a broader range of modes of being in the world, the bipolar structure of revenge cannot release him to do so. Revenge might present itself as a choice, but always ends as a kind of compulsion.

Czollek’s own poetry goes beyond the revenge his polemic imagines. The ambiguous ending of his poem “Golem in the Cycle”—which asks if the murderous golem understood his mandate better than his maker—can be read in at least two ways. The first articulates a potentially eternal antagonism. Here, the golem, charged with defending the Jewish community, knows that the people of Prague will continue to persecute its Jews in the centuries to come—and so he kills them, attempting to preemptively eliminate the danger. In the second reading, which works against this bleak fatalism, the golem speaks rather of the dangerous potential of revenge to overcome the avenger. Called forth against violence, he ultimately becomes an instrument of violence rather than justice. The poem ends, then, as a cautionary tale about revenge. Czollek is aware he is caught within a golem of his own making—doomed to polemicize against the current state of Germany rather than for the de-integrated future.

Czollek has made a strong case for why Germany’s Theater of Memory must change, not least through the way he seems to have become entrapped in his own vision of vengeance. But, as he cannot help but know, there are other roles that resist those assigned by the Theater of Memory—all of those in the vast spectrum of possibilities besides victim and avenger. This knowledge is there in the final plea with which the book ends—a plea for a radical heterogeneity of society and self, and an escape from the limitations of the performances Czollek finds himself conscripted into: “De-Integrate Me!”

A previous version of this article stated that Maxim Biller was born in the former Soviet Union. In fact, he was born in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic.

Sanders Isaac Bernstein is a writer, reader, and theatergoer living in Berlin. His work has also appeared in The Baffler, newyorker.com, Coda, and The Bad Version, which he founded and edited from 2011 – 2014.