Letters / On “Shall We Not Revenge?”

I would like to communicate my thanks to Sanders Isaac Bernstein for this engaged take on my work. I am not exaggerating when I say that I have rarely, if ever, seen such an in-depth discussion of my work in a German-language outlet. And I hope to respond with the same kindness and seriousness that I sense in the article.

I would like to start by pointing out with a smile that Bernstein’s argument—that my proposed counterstrategy remains trapped within the mode of thought it critiques—is a classic within a certain brand of left-wing thought; the Catch-22 of dialectics, if you will. I would stress that we should be careful not to fool ourselves into believing that we can truly move beyond the systems we criticize. In my opinion at least, this is not feasible in the present—if ever. I’d even argue that the emancipatory critique, in striving to reach this place beyond, runs the risk of promising something that neither criticism nor activism can ever truly achieve.

The issue connects to the ever-relevant question of how to move from the unredeemed present to a better future. To this I would answer: If the revolution is ever to take place, rather than to remain a messiah-in-the-coming, we will have to be very patient. Take as a model the cup we put on the table each Passover to anticipate the arrival of Eliyahu Hanavi. This also represents the necessity of ongoing repetition when it comes to the things that remain true—about the need for justice, self-determination, equal treatment, etc. In this tedious process of waiting, pop culture may play an important role, because it helps us reframe familiar material so that people (including ourselves!) are not bored to death in the meantime. In other words, it helps us stay fresh.

When I reference the idea of “revenge” in my work, I perceive it much more in this sense of freshness than of redemption, as the author implies. Revenge, as I conceptualize it in the context of my call for de-integration, does not aim to liberate Jews from the German Theater of Memory, or to attain any position outside the present order. Rather, it strives to reestablish what one might call Jewish humanity. I believe that this is a precondition for facing so much of what cannot truly be discussed so long as the Theater’s Jewish actors maintain a self-image determined by pure, innocent, and ultimately passive victimhood. In this sense, revenge is not about escaping the present at all, but about realizing how implicated we are as Jewish subjects in this world.

Berlin, Germany

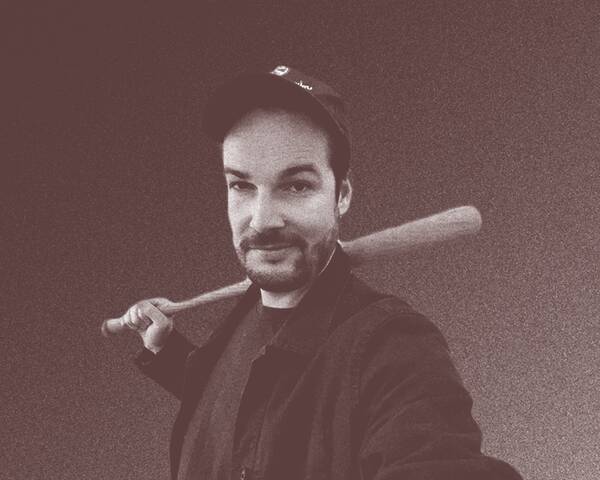

The letter writer is the author of De-Integrate!: A Jewish Survival Guide for the 21st Century.

Sanders Isaac Bernstein’s critique of the fantasy of revenge for the Shoah feels almost completely right. As a history teacher, when my students would ask if I’d seen Inglourious Basterds, I’d tell them that I don’t waste my time with myths and fables about the destruction of Europe’s Jews and so many others.

If there is one flaw in Bernstein’s exposition, it is in failing to situate different revenge fantasies historically. The idea’s appeal to someone like Abba Kovner, a poet, writer, and activist who survived the Holocaust in Europe, must differ from its hold on Max Czollek, a third-generation survivor who has grown up in a Germany where “the Jew” carries far too much symbolic weight.

For many of the previous generation, like my Polish Jewish father who fought in the Soviet Army, the desire for revenge eventually receded. They had other fish to fry; revenge and its consequences would surely have gotten in the way of creating new lives. As a child of survivors, such visions of vengeance were never part of my upbringing. The playground games I played with other children in our refugee community modeled the stories of survival we heard around the house and rarely—if ever—included any desire for revenge.

And yet, for Czollek’s generation, the fantasy of revenge seems to increase in appeal the farther from the Shoah we get. Cycles of revenge are everything Gandhi and Dr. King said they are: downward spirals of violence. Clearly, for Czollek, revenge remains in the realm of fantasy. But in an increasingly reactionary political landscape, Czollek’s rising bile would be better channeled through tikkun and the left struggle for the oneness of humanity. Revenge takes up way too much space on this ailing planet. We don’t need any more, whether in word, deed, or absurd movies.

Westbrook, Maine