Ruins of the Israeli Bund

A photo essay documents the remnants of the shuttered home of the Arbeter Ring in Tel Aviv.

Given the state of Israeli politics in 2019, it’s a wonder that the Arbeter Ring—the stalwart Bundist organization that shares a name with the US-based Workmen’s Circle—survived in Israel as long as it did. The Tel Aviv outpost of the organization, which finally closed down this summer, was half-hidden on the bottom two floors of an unassuming apartment building on Kalisher Street, nestled among hipster cafés and expensive restaurants. For more than 60 years it served as the home of the Bund in Israel, a center dedicated to left-wing and Yiddishist politics, struggle, culture, and community. But no longer.

The shuttering was not without controversy. In 2007, Beit Shalom Aleichem, Israel’s largest Yiddish organization, took ownership of the building that housed the Arbeter Ring and promised to maintain it and pay off its debts. This year, claiming that it can no longer afford to pay for the building’s upkeep, Beit Shalom Aleichem was forced to close the Arbeter Ring and announced that it would sell the property. A generation of younger Yiddish activists, who had become involved and invested in the center, have been harshly critical of this development, suggesting that the closure was ideologically motivated. These critics view Beit Shalom Aleichem’s leadership as uninterested in—or even actively opposed to—Arbeter Ring’s socialist diasporism; they claim that Beit Shalom Aleichem gave the Arbeter Ring a bad deal in order to obtain a valuable real estate asset.

Realistically, though, the clearest reason for the Arbeter Ring’s closing has been the failure of the Bund in Israel to connect sufficiently with younger generations that might have been able to preserve its legacy. For anyone interested in the history of Yiddish or the Bund in Israel, it is clear that the failure to continue to maintain it as a cultural center, or at least to preserve it as a museum, represents a significant loss.

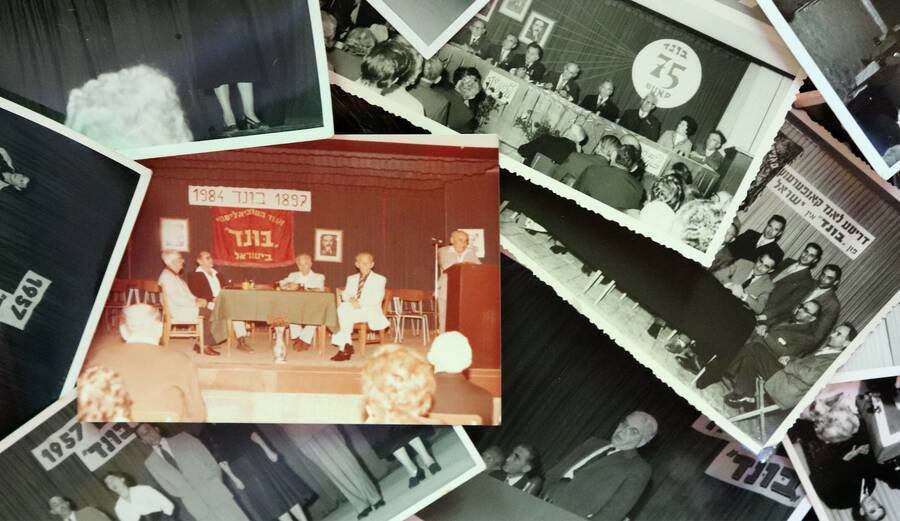

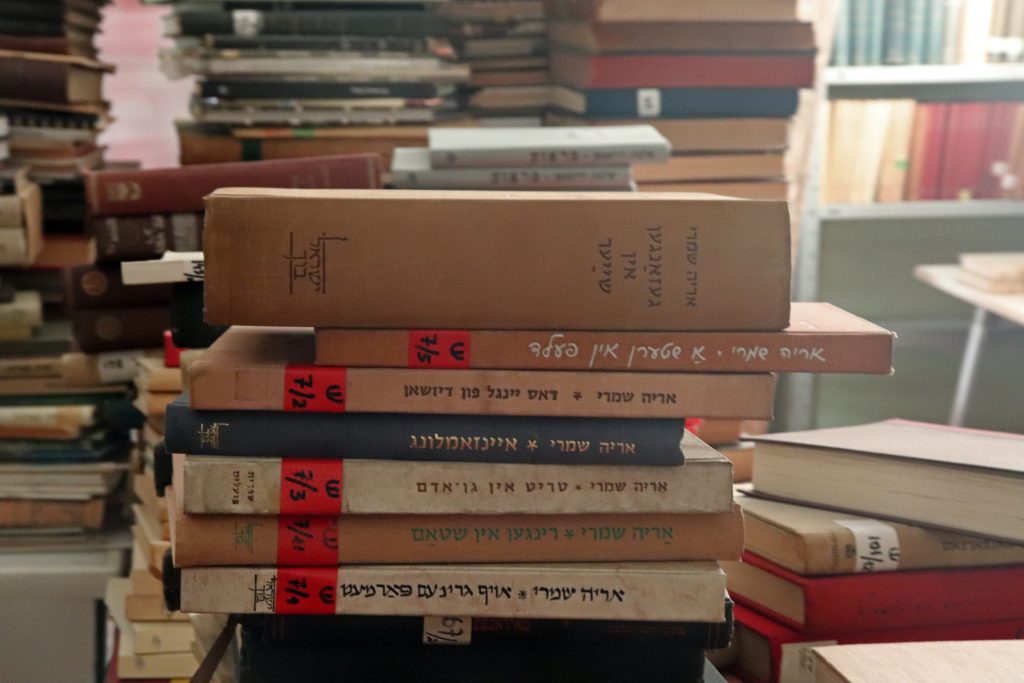

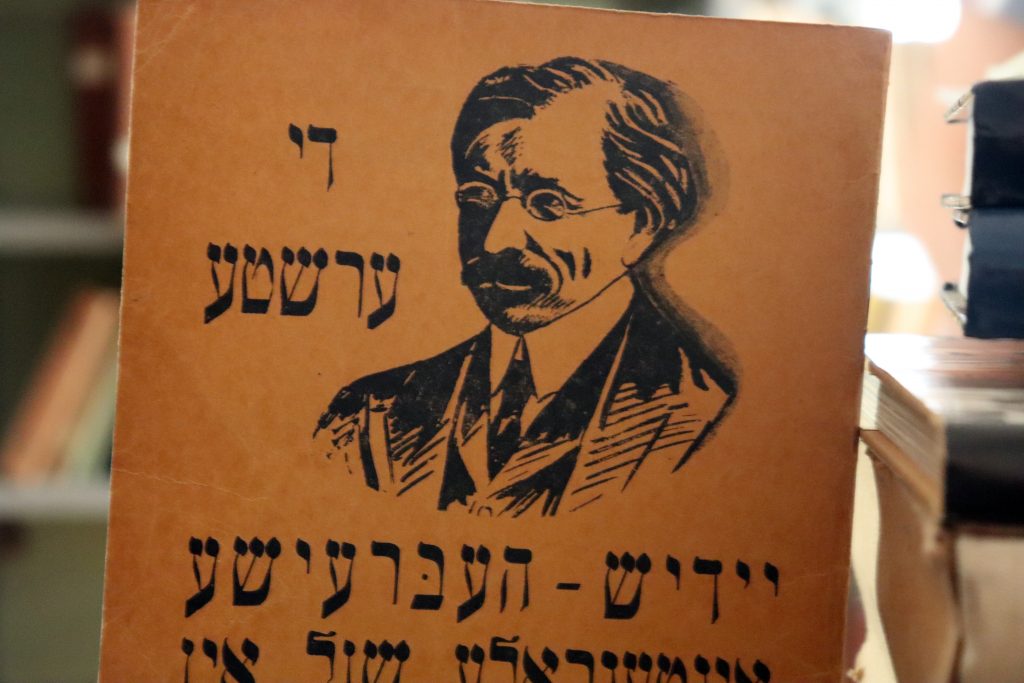

This August, the photographer Ethan Schwartz and I visited the site to document the space in its final moments. We walked through the rooms of the Arbeter Ring—an events hall, a library, and the editorial offices of Lebens-Fragen (the monthly journal of the Bund in Israel)—and watched as books, paintings, portraits of Bundist dignitaries, photographs, and banners were hastily removed. We could still sense something of what made this space so special.

The Arbeter Ring offered a striking contrast to Tel Aviv’s Zionist, Hebrew-speaking dominant milieu. When the building was built and opened in August 1957, its purpose was to serve as a communal home for those who still believed in the revolutionary principles of the Bund, like Jewish liberation in the diaspora and Yiddish secular culture, even as they lived in the new Zionist state. The building was to be a significant hub for dances, activities for children, political congresses, lectures, and other forms of intellectual and cultural production. (Lebens-Fragen, which predated the building—it was founded in 1951—and was heroically edited by Yitskhok Luden for 43 years until it folded in 2014, is an important historical and cultural source in its own right.) Around this modest edifice, a secular, socialist Yiddish subculture flourished. The Arbeter Ring was the last bulwark of an alternative political culture, a challenge to the rest of the city.

The memorialization of the center and its activities is already well under way, most notably in the work of filmmaker Eran Torbiner, whose documentary on the subject is available to watch on YouTube, and scholar Gali Drucker Bar-am, who has done excellent work on the center and Yiddish in Israel. In this photo essay, we wanted to pay tribute to the building itself—to try and capture some trace of what flourished there. The center united politics and culture at the heart of a community trying to open the Yiddish and Bundist traditions to everyone who wanted to be a part of them. With its closure, a certain point of access to these roots is irrevocably lost.

– William Pimlott

William Pimlott is a PhD student in Yiddish and British Jewish history at University College London.

Ethan Schwartz is a writer and photographer who lives in Tel Aviv.