IN ISRAEL there is a town where the people have no addresses. Some 800 people live there, in 130 buildings on 55 acres, just 20 minutes southeast of Tel Aviv, in the shadow of the high rises of Lod and Ramle. But the town, for all official purposes, does not exist. Because it does not exist, it looks nothing like most of the cities that span Israel’s populated center. The villagers pile up their garbage because no municipality collects it. There is no hookup to Israel’s state electrical grid; before one resident paid for a private line, the entire village operated on gas. The village has no streetlights, no proper sewage system. Every time it rains, says the town’s attorney, the town transforms into “an Arab Venice.” This town is called Dahmash.

Over 30 years ago, Farida Shaban married a man who was born in Dahmash and went to live with him. In 2003, they built a house there. Because it had no official permit, the house was immediately slapped with a demolition order. For four years, they waited. Then, early one morning, the authorities came. Shaban was getting ready to take her kids to school in nearby Lod when she saw a large group of police officers amassing nearby. She made her way back to her house with her children and locked the doors. At the time, her youngest daughter was three. The kids, she said, refused to leave the house. The older ones told the officers, “If you want to destroy it, destroy it while [we’re in it].”

The authorities left the village to regroup—and in the hours it took for them to return, the Shaban family was able to rush to the local court and obtain a stay on the demolition. The police backed down.

It wasn’t demolished that day, but Shaban’s home has never been safe. She told me she lived for years without a kitchen, cooking next door at her sister-in-law’s: “I said, what, I’ll make a kitchen, invest, and in the end, they’ll destroy it? So [for] three or four years I didn’t have a kitchen.”

Her house escaped demolition twice more—once in 2010, when the authorities were forced to back down amid a joint Jewish–Arab outcry, and again in 2014, when nearly a quarter of all the homes in Dahmash (16 out of 70 at the time) faced imminent demolition. That fall, instead of demolishing all 16 homes, the authorities took their bulldozers to just three, and Shaban’s was not among them. Still, she said, since that day in 2007 when her children faced down the authorities, her family has lived in uncertainty. They go to bed at night unsure if their house will be demolished in the morning. “It’s like being caught between the ground and the sky,” she said.

Residents of Dahmash like Farida Shaban are Palestinian citizens of Israel, mostly descendants of those who fled their homes in 1948 when Israel declared independence and war broke out. They came from what are now majority Jewish cities like Ra’anana, Beit She’an, and Gadera and were offered a take-it-or-leave-it deal as compensation: move to the tiny town of Dahmash. But, even as they were told they would be full Israeli citizens, and that they owned the land, the village was never “recognized” for residential building. This meant no infrastructure could be built, no urban planning would ever be done. The village of Dahmash has no schools, no green spaces, no regular public transportation. It does not appear on official Israeli maps. It sits between the ground and the sky.

To understand how successive Israeli governments have kept Dahmash in a condition of legal limbo requires an exploration of the Israeli state’s obsession with territory. This obsession, translated numerous times into law, has left Israel’s Arab minority, more than 20% of the population, with jurisdiction over only 3% of Israel’s land. Since its founding in 1948, Israel has built some 900 townships for Jewish residents, and none for a growing Arab population (with the notable exceptions of seven townships that were built to forcibly urbanize the Bedouin people in the Negev). Meanwhile, Arab towns in Israel have increased in population density 11-fold since 1948, but are prevented, in most cases, from legally expanding in any direction but up.

As illegal building has increased to respond to population growth, so have the penalties. A 2017 legal amendment, known colloquially as the “Kaminitz Law,” imposes exorbitant fines and sentences of up to three years in prison for illegal building. An illegal home of 100 square meters can result in a fine of approximately 300,000 shekels, or $88,000—a sum few can afford. Still, as of May 2020, the Center for Alternative Planning in Israel estimates that 15–20% of all homes built by Arabs are built without a permit.

Almost 73 years after the founding of the state, tens of thousands of Israel’s Arab citizens still live in unrecognized nowhere zones, spaces that are, paradoxically, permanently temporary.

What is sometimes overlooked in the wake of a home demolition is that it destroys not only a physical shelter, but a legal one as well—forcing Arab citizens into a bureaucratic purgatory of court cases and legal fees. Almost 73 years after the founding of the state, tens of thousands of Israel’s Arab citizens still live in unrecognized nowhere zones, spaces that are, paradoxically, permanently temporary.

Dahmash is neither a Bedouin encampment deep in Israel’s southern desert, nor a tent village tucked behind a West Bank hill. It sits smack in the middle of Israel—symbolically, perhaps, at the center of the Zionist dream. And as the current Israeli government strategizes over when and how to annex parts of the West Bank, the laws that currently apply within Israel—laws that neglect, ghettoize, and criminalize Arab residents—will provide the foundation for a retroactive legalization of the land grab in the West Bank that began long ago. In other words, annexation will likely bring us the story of Dahmash over and over again.

THERE IS A DISCERNIBLE THROUGHLINE that runs from Zionism’s early ethos of Jewish land ownership and cultivation into the lawbooks of the modern state of Israel. Motivated by centuries of bitter antisemitism in European nations, the early Zionists sought to be peasants and pioneers in a land of their own. A good number of them did not much care which land—there were proposals for the settlement of Uganda, Crimea, or even, as Theodor Herzl contemplated in The Jewish State, Argentina—so long as they were free to govern themselves and there was land for them to farm. According to Israeli historian Anita Shapira, they saw the society they were building as a direct refutation of the antisemitic canard that “Jews are parasites that live on the backs of other people,” indisposed to physical labor. The antisemite’s image of the Jew had a strong influence on these settlers in Palestine. “They wanted to show that Jews can cultivate the land, that Jews can build the land from the bottom up,” Shapira said.

The Jewish National Fund began buying land in Palestine in 1904. Its mission was in line with early Zionist aspirations: The JNF would be the “trustee and custodian” of land it purchased, which would remain the “perpetual property of the Jewish people.” “The realization that the first step in the struggle for a Jewish Homeland is the struggle for land is one of the basic principles of Zionism,” wrote JNF director-general Abraham Granovsky in 1940. “Land is the indispensable foundation for any human activity. Without it, there can be no agriculture, no urban settlement. The first task of a landless people is to provide this foundation for its existence.”

Today, the JNF owns roughly 13% of the total landmass of contemporary Israel. But its charter to buy and administer land “solely for Jewish people” has not changed. The JNF does not sell or lease land to non-Jews and remains a central para-state instrument for the continued dispossession of Arab citizens and residents.

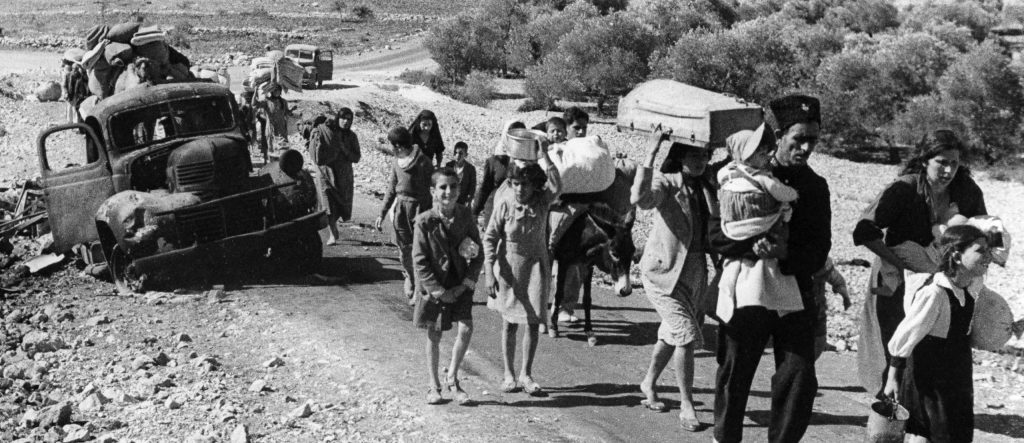

Israel gained its independence in 1948 in the midst of war. During the fighting, more than 700,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled from their homes in what Palestinians call the “Nakba,” or “catastrophe,” and left behind huge amounts of unattended property. David Ben-Gurion, the new country’s first prime minister, wrote in his diary about the mass exodus of Arabs from Haifa, calling it “an amazing and terrible sight.” He described “a dead city . . . with not a living soul except for some wandering cats,” and asked: “How did tens of thousands of people leave behind, in such panic, their houses and wealth?”

According to Shapira, Ben-Gurion viewed the departure of hundreds of thousands of Arabs—many of whom saw their villages destroyed during the 1948 war—as a miracle. He had feared the prospect of governing a Jewish state with only a small Jewish majority, and now he would not have to; only around 160,000 Palestinians stayed in what became Israel after the war. Of the 35,000 Arabs who had lived in Ramle and Lod, for example, only 2,000 remained.

The departure of so many Palestinians changed the calculus for the fledgling state. The new Israeli government was not prepared for a mass exodus, nor did it anticipate the abundance of land left in its wake, and it moved quickly to take advantage of the facts on the ground, working haphazardly to concentrate Arab residents in designated cities and neighborhoods. In heavily Arab cities like Haifa, Jaffa, and Lod, the authorities moved Arab populations into a single area, put them under curfews, and even physically fenced them in with barbed wire. Gad Machnes, the director general of the short-lived Ministry of Minority Affairs, registered his horror, referring to such areas as “concentration camps.”

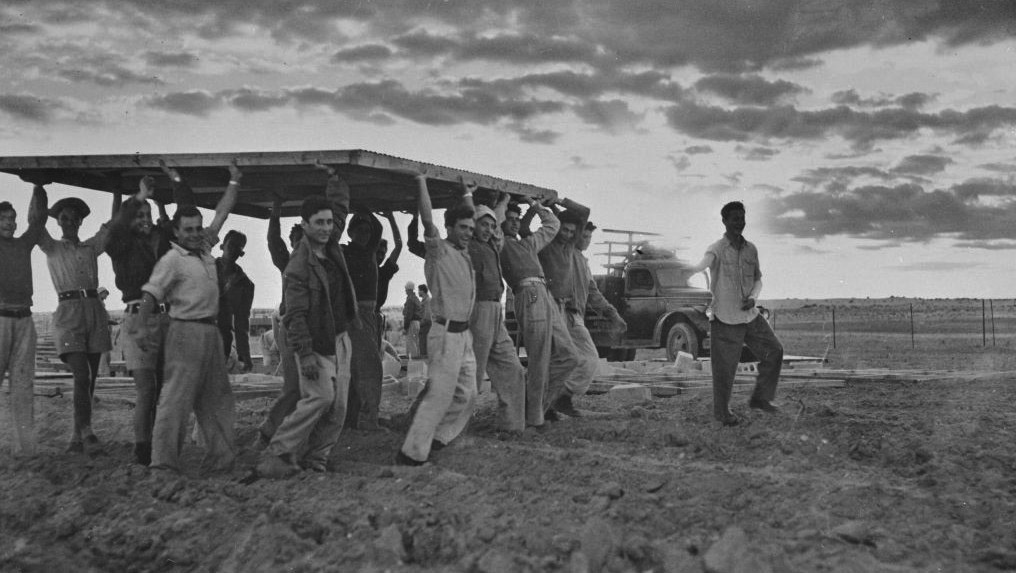

Around the same time, local Jewish residents, including Holocaust refugees, started taking over houses. Members of early kibbutzim and moshavim, often built on JNF land, cultivated agricultural land that Palestinians had left behind during the fighting. This was, above all, a practical move. Israel’s Jewish population doubled in its first three years of existence, and according to Palestinian American legal scholar George Bisharat, Arab property that had been abandoned “played an important role in providing for the needs of these newcomers.” Indeed, Bisharat recounts that 350 out of the 370 Jewish settlements established between 1948 and 1953 were located on what had been Arab property.

By midsummer 1948, Israel’s new ministries of Agriculture and Finance were working directly with the Jewish settlers to help formalize and sanction what had been a chaotic, mostly bottom-up appropriation of Arab lands. They passed emergency regulations that created the initial legal frameworks for land seizures and reallocation, like the “Cultivation of Fallow Lands and Unexploited Water Resources,” issued in October of 1948. According to legal historians Geremy Forman and Alexandre “Sandy” Kedar, it was this regulation that empowered the Agriculture Minister to retroactively legalize the seizure and reallocation of land—the first state policy of its kind. These emergency measures, moreover, “introduced a framework and terminology” that would soon become “a central, permanent component of Israel’s legal treatment of appropriated Arab land.”

In 1950, the Knesset passed a law granting the state sweeping powers to appropriate and redistribute “abandoned” Arab land. The Absentee Property Law, based on an emergency regulation of the same name, applied to anyone who owned land in the state of Israel but left for any amount of time after November 29th, 1947—the day the UN passed a resolution allowing for Israel’s creation—for what might broadly be described as “enemy territory”: either in one of seven Arab countries listed by the law, or in an area not yet controlled by the state of Israel in the greater “land of Israel.” It deemed all such persons “absentee” property owners, and declared that land belonging to “absentees” could be confiscated by the state.

As many as 75,000 Palestinians—15% of Israel’s Arab citizens—became internal refugees during the Nakba, and were now considered “present absentees”: physically present on their land, but legally absent.

By this definition, a significant portion of the Arab population in the new state of Israel was now considered “absentee,” including people who had returned to their homes after the fighting subsided. If someone from Haifa was determined to have fled—even for a day—to Amman or Bethlehem, their land passed into the hands of the dubiously named “Custodian of Absentee Property.” As many as 75,000 Palestinians—15% of Israel’s Arab citizens—became internal refugees during the Nakba, and were now considered “present absentees”: physically present on their land, but legally absent. Lands expropriated from them under the Absentee Property Law were transferred to para-state bodies like the JNF and offered for Jewish settlement and cultivation.

The parents of Dahmash resident Arafat Ismail faced the paradox of present-absenteeism. They fled their home, a town called Qatra (on which land the Israeli towns of Kidron and Gadera now sit), during the hostilities, and the state refused to allow them back after the war. They took the deal offered by the government to go live in Dahmash, but many others elected to submit claims to their property. This turned out to be a long shot for Arab property owners. It was difficult to prove that they had been present on their land amid the chaos of wartime, and often, the land had already been swallowed up by a new kibbutz or moshav. A decade after the war, only around 200 claims had been granted.

The state recognized that the Absentee Property Law might be subject to serious legal challenges by present absentees. In 1953, lawmakers attempted to avoid being forced by the courts to return Arab property by passing the Land Acquisition (Validation of Acts and Compensation) Law; Eliezer Kaplan, the minister of finance who presented the law to the Knesset, would describe it as an effort to “instill legality in some acts undertaken during and following the war.” Under this new law, the state would retroactively legalize all land seizures on the grounds of “security,” “settlement,” or “development.” Over the course of a year, the law enabled the expropriation of 1.2 million dunams, or about 300,000 acres.

THE ABSENTEE PROPERTY LAW and the Land Acquisition Law were two among several new laws passed early in Israel’s statehood that prevented the residents of Dahmash from returning to the property they owned before the war. But it is yet another law, introduced a decade later, that keeps their homes in legal limbo and their eyes fixed on the courts. The Planning and Building Law, passed in 1965, was officially intended to regulate and manage all land use in Israel, setting up bodies to oversee planning on the national, district, and local levels. Crucially, it also distinguished, via zoning, between urban and agricultural land—an expression of anxiety, according to Kedar, that if land was not expressly set aside for agricultural purposes, Jews might regress into the weak urbanites they had been in diaspora. On paper, the law is not inherently discriminatory. In practice, however, it is often selectively applied in order to prevent Arab neighborhoods and towns from legally building or expanding, and it immediately gave rise to the phenomenon of “unrecognized” Arab villages across Israel.

The Planning and Building Law has been used to execute thousands of demolitions a year—sometimes a latrine, or a shepherd’s tent; sometimes whole villages. These demolitions take place primarily in Israel’s southern Negev region (the Naqab, in Arabic), home to 35 unrecognized villages. “The authorities will just come in and demolish anything, from the entire house to a section of the house—just the porch, or the staircase,” said Amjad Iraqi, an editor for +972 Magazine who previously worked for Adalah, a legal center for the rights of Palestinian citizens in Israel. “People are familiar with this from the occupied territories, but it’s always been a problem for Palestinian citizens.”

Dahmash sits on land Israel zoned for agricultural use in 1984. This means that any structure built there for nonagricultural purposes—like a home—was deemed retroactively illegal and subject to demolition. It turned Dahmash residents into lawbreakers overnight. “The state pulled the wool over our parents’ eyes twice,” Arafat Ismail told Israeli television. “On the one hand, they didn’t return their land when they demanded it . . . and on the other hand . . . it gave them agricultural land where it was forbidden to build!”

Since 1996, the state has issued 13 demolition orders in Dahmash. In the 1990s, there were only a few dozen homes in the village, at least ten of which had permits granted back in the British Mandate period. But families were growing, and so were the number of homes. The order was part of a broader move away from confiscation and toward state enforcement of restrictions on planning and building. According to Mysanna Morany, the coordinator of the land and planning unit at Adalah, once the Israeli state had absorbed as much land as it could under the Land Acquisition Law, it began using planning tools to limit Arab growth on land they still privately owned.

In the next several years, a number of demolition orders were issued in Dahmash, though very few were actually carried out. In 2004, 17 homes in Dahmash were hit with demolition orders—all on the basis that they were built on “agricultural” lands. According to a Human Rights Watch report, Yoel Lavi, the mayor of nearby Ramle at the time, told an Israeli newspaper that the authorities in Dahmash should “take two D10 bulldozers, the kind the IDF uses in the Golan Heights, two border police units . . . and go from one side to the other.” In 2006, the authorities carried out some of the orders, demolishing four “illegal” homes.

It was at this point that the villagers, with the help of attorney Kais Nasser, a specialist in Israeli zoning and planning law with a focus on Arab towns, along with the Arab Center for Alternative Planning, submitted a master plan to the regional planning and building committee that would save their homes from demolition and keep them where they were. It included a request to change the zoning regulations for Dahmash to allow them to build residential structures. The authorities did not respond for 18 months. Only when the district court ordered the discussion, finding that the committee had “abstained from discussing the plan,” did the committee finally consider it. Zoning “is not a decree from heaven,” the court reminded them.

But in 2010, the committee nonetheless rejected the plan. Because the town didn’t officially exist, they said, the question of planning was irrelevant: The plan, as presented, would require the establishment of a new town, and since this action was the sole purview of the government, there was nothing the committee could do. Nasser noted at the time that the committee “completely ignored the fact that we are talking about a village that has been standing for decades,” and that, in fact, predated the state. Dahmash’s case was kicked to Israel’s Interior Ministry, where its internal committees passed the buck among themselves for years. “We suffered from ping-pong. And the demolitions didn’t stop,” Nasser said. The government, it seemed, was deciding not to decide.

In 2014, 16 demolition orders were again scheduled, this time for the middle of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, in a hot and muggy July. Among those houses set to be demolished was Farida Shaban’s home. At the time, she told an interviewer with Israeli radio how psychologically taxing the years of limbo had been. She and her husband had built their house more than a decade earlier. Since then, she said, they “lived from court date to court date. What does that mean? . . . Anything you’re planning . . . [you] push off until the next date.”

Nasser appealed Dahmash’s case to Israel’s High Court of Justice. “I requested a very simple thing,” he said: that the court might “require the state to . . . pronounce this village, a village.” Seven years after the villagers had presented their master plan to the regional council, they had a glimmer of hope that they might keep the demolitions at bay. The case itself, said Nasser, “was a kind of informal recognition that the village exists, and you can’t evade responsibility.” And still, that same August, the court case still pending, bulldozers returned to Dahmash. Israeli authorities demolished three uninhabited residences belonging to the Assaf family. The homes, built after Dahmash’s case went to the Supreme Court, were considered “new construction” and therefore subject to demolition.

It wasn’t until 2016 that the villagers saw a rare victory. The High Court issued a conditional order that the state must provide an answer to the question of the village’s status: Either it should be declared a new, independent settlement, zoned for residential use, or it should be incorporated into another municipality. It also instructed the state to ensure that, in the interim, the regional council provide the village with basic services. The Israel Lands Authority appointed a planning committee to those ends.

A follow-up discussion was scheduled to take place at the High Court on July 6th of this year. But the date was pushed back; the state had nothing to offer the court by way of updates. They hadn’t even made a final decision about how to erect streetlights or facilitate garbage pickup, as the court had ordered. According to Nasser, the deferral of the court discussion means the village is now “back in the same cycle”—all because Dahmash was “guilty of being born an Arab village.”

There has been no significant legislative overhaul, no good-faith attempt at reform. At this point, the application of these laws must be understood as the system functioning as it should.

It is difficult to ascribe intention to legal history, to grasp exactly how the new state and its Jewish citizens understood what they were doing to the Arabs caught in their midst. But Dahmash—suspended in permanent temporariness, a somewhere that is officially nowhere—is a testament to the way these laws continue to be applied, with little incentive to change course. Arabs living in unrecognized villages have organized, forming democratically elected bodies like the Regional Council for the Unrecognized Arab Villages in the Negev and the nonpartisan National Committee of the Arab Local Authorities. Nonprofits like the Negev Coexistence Forum for Civil Equality and the Arab Center for Alternative Planning have long advocated for Arab planning rights. Their small victories have been hard-won: the stays of eviction, the handful of unrecognized villages now recognized, better budgets for Arab municipalities. But the legal regime of dispossession remains. There has been no significant legislative overhaul, no good-faith attempt at reform. At this point, the application of these laws must be understood as the system functioning as it should. And, like the Absentee Property Law, that system proliferates throughout the “land of Israel,” even beyond the “state of Israel.”

AHMED SUMARIN, now in his 30s, has faced eviction from his East Jerusalem home since he was six years old. His great-great-uncle Musa built the house in 1950, 17 years before East Jerusalem, including his neighborhood of Silwan, was annexed by Israel after the Six-Day War. But in 1989, after Musa had been dead for five years, the government declared Musa’s heirs “absentee,” and designated his home “absentee property.” Two years later, it transferred ownership of the house to Himnuta, a subsidiary of the Jewish National Fund, which has been trying to evict the 18 members of the Sumarin family from their home ever since. Like Farida Shaban’s family in Dahmash, the Sumarins have spent endless hours in court, seemingly to no avail. “We can’t imagine where we’ll go,” Wardeh Sumarin told New Internationalist in 2018. “We were born here, our family is here. Our work, children and school are here. I can’t tell you what we’ll do because my life is in Silwan.”

On June 30th of this year, in what may be the end of the line for the Sumarins, the court upheld the claim, brought by the settler group Elad, that the house Musa built can be legally designated “absentee property.” The court gave the Sumarin family 45 days to vacate. Then, on August 5th, the Supreme Court issued a stay of the eviction order, valid until the end of November. Until then, the Sumarins will work to appeal the decision one last time.

Awdeh Hathaleen lives a little over an hour’s drive south of the Sumarin house, in the West Bank village of Umm al-Khair. The village is home to 170 people, descendants of Bedouin who in 1948 fled to the South Hebron Hills from what is now the Israeli city of Arad. They bought the land they now live on from other Palestinians in 1949 and, for a number of decades, lived much as they had before, keeping livestock and dry farming. But in 1980, more than half the villagers’ land was grabbed under military seizure order 12/80, which covered some 2,940 dunams of land belonging to the nearby town of Yatta. This type of seizure was recognized by Israel’s High Court as legitimate on the basis of “military needs.” Mainly throughout the 1980s, Israeli authorities sometimes took land that they had ostensibly seized temporarily, permanently declaring it “state land,” and transferring it to settlements. And so it was with the land belonging to Umm al-Khair: The IDF built a military outpost on the village’s land, and in 1983 declared the area “state land,” transferring it to another para-state body, the World Zionist Organization’s Settlement Division, which, in turn, established a permanent settlement there.

Today, the air-conditioned homes of Carmel—a settlement once described by Nicholas Kristof as “a lovely green oasis that looks like an American suburb”—sit across from the run-down shanties of Umm al-Khair, separated by a barbed wire fence. Carmel’s settlers built a chicken farm on the far side of Umm al-Khair and ran electrical wires directly over the heads of the villagers. “The humans are not allowed to get electricity, while the chickens have electricity 24 hours,” Hathaleen told me. Umm al-Khair itself is powered by a handful of solar panels, donated by an NGO and subject to electricity shortages in winter. Hathaleen, who is 25 years old, was married last year. His wife is pregnant with their first child, due in September. “I have plans until we have the baby,” Hathaleen told me. “But I don’t want to plan for something [beyond] now.”

There is good reason to suspend any major plans for the future. The Israeli government’s stated intent to annex parts of the West Bank would leave Hathaleen even more vulnerable. Due to a technicality dating back to a 1967 Israeli census of the West Bank, the population registry lists Palestinians living in what has been known since the Oslo Accords as Area C—rural areas ruled entirely by the Israeli military’s civil administration—as living in the nearest Palestinian city. This means that a Palestinian like Hathaleen, who has lived his whole life on the cracked earth of Umm al-Khair, is currently registered as a resident of the overcrowded southern West Bank city of Yatta. Should Israel annex Umm al-Khair, it could acquire the land, but not the people, who are legally registered as residents elsewhere. This would make the residents of Umm al-Khair trespassers—or in legal parlance, “illegal aliens”—on their own land.

AWDEH HATHALEEN OF UMM AL-KHAIR, Ahmed Sumarin of Silwan, and Farida Shaban of Dahmash live in different places, and are governed by different aspects of Israeli state authority. Dahmash is a part of Israel; Farida Shaban is a citizen of the state. East Jerusalem was annexed in 1967, and Ahmed Sumarin holds the precarious status of “resident,” granting him some benefits of citizenship, but leaving him without an Israeli passport or the right to vote in national elections. Umm al-Khair in the West Bank awaits news of annexation by the Israeli government; either way, Awdeh Hathaleen will likely remain a citizen of no state. And yet, the policies that affect each of their lives—policies that reach back to the very beginning of the Israeli state—all have the same basic structure: Their property can be seized. That seizure can be retroactively legalized. That legalization can ensnare the land in state bureaucracy, shuffling it around until it ends up in Jewish hands. Individuals, families, and whole villages can be categorized as “there but not there,” stuck in permanent legal states of temporariness: present absentee, unrecognized, illegal. Fights in the courts are inconclusive, as the state decides not to decide.

Conventional wisdom says that annexation would make permanent Israel’s occupation of the West Bank. And indeed, annexation would formalize the operative system in the Palestinian territories, in which one population has rights and another does not—a system the Israeli human rights organization Yesh Din has recently argued could be legally classified as apartheid. But if you ask human rights NGOs that operate in the West Bank, they will tell you annexation is already happening. Israel has already enacted some eight laws over areas where it is not recognized as sovereign, over a population it does not represent. The human rights community calls this kind of legislation “creeping annexation.” In 2017, Israel passed the “Regularization Law” (known by critics as the “Expropriation Law”) that would have legalized settler outposts—ones Israel itself otherwise considers illegal—by retroactively expropriating the private Palestinian land those outposts sit on. The law was struck down by the High Court this summer, but Israel’s Attorney General, Avichai Mandelblit, has already offered other legal methods for expropriation that would not require such a law. In January of 2018, Mandelblit made it mandatory that any new bill proposed in the Knesset include a legal opinion that sketches out how it might be applied to the settlements.

The groundwork has been laid, with or without formal annexation: The next major Israeli land grab will not operate hilltop by hilltop, as the settlers do, but law by law. And it is likely to leave even more Arabs who live in the land of Israel stuck somewhere between the ground and the sky.

Elisheva Goldberg is the media and policy director for the New Israel Fund and a contributing writer for Jewish Currents. She was an aide to former Israeli Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni and has written for The Daily Beast, The Forward, The New Republic, and The Atlantic.