Residents of all the neighborhoods: Unite!

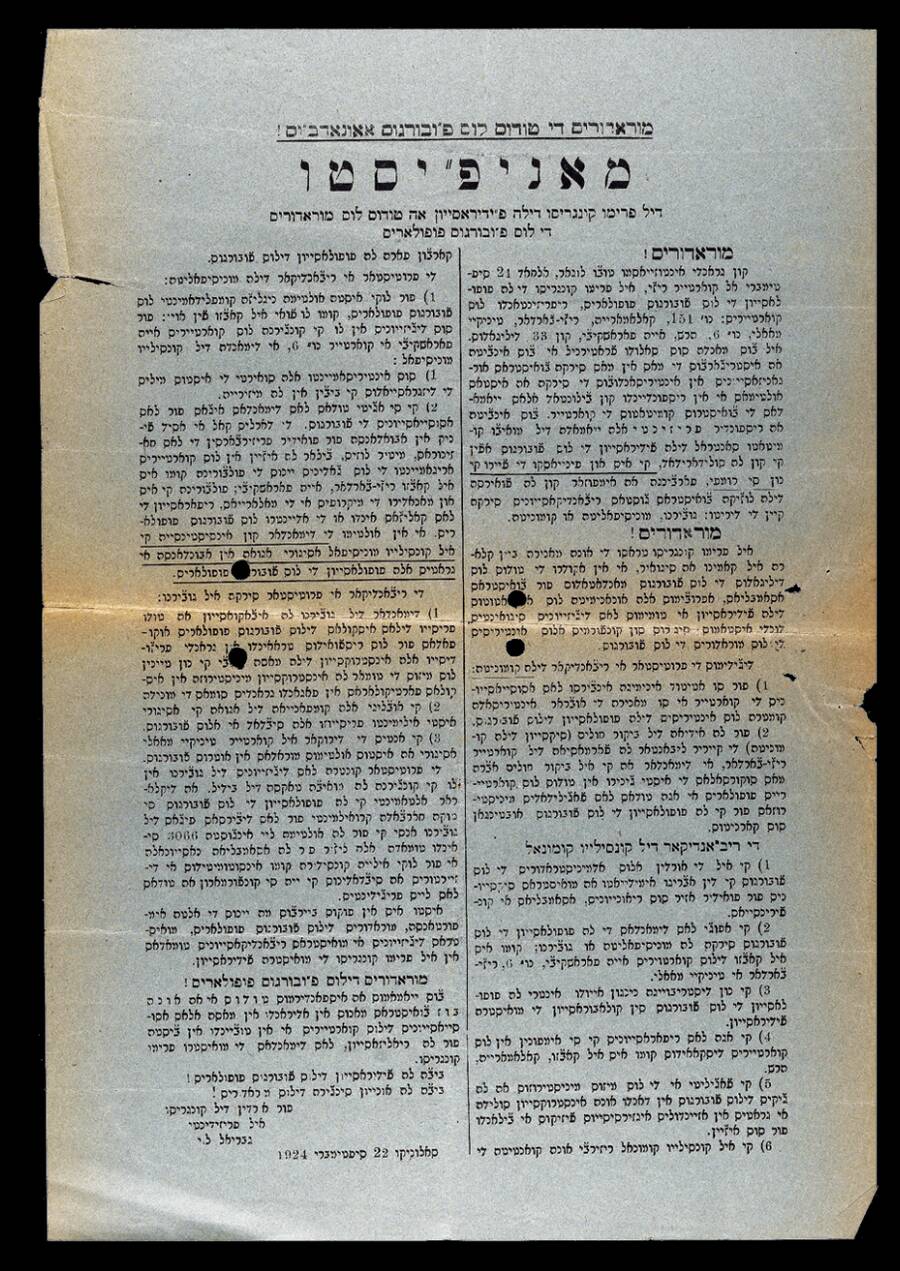

A new translation of the “Manifesto of the First Congress of the Federation of Residents of All the Popular Neighborhoods of Salonica” from 1924.

This article appears in our Fall 2020 Housing Issue. Subscribe now to get Jewish Currents in your mailbox.

The rise of industrial enterprise in the late 19th century turned Salonica into a major commercial entrepôt in the eastern Mediterranean for flour, tobacco, bricks, and other goods. A cadre of wealthy Jewish families owned many of the factories, while a vast, mainly Jewish working class—women as well as men—toiled in poor conditions. With the introduction of a new Ottoman constitution in 1908, Jewish workers united with their Greek, Bulgarian, and Turkish counterparts to form the Socialist Workers Federation of Salonica, which initiated strikes and demonstrations and won major concessions in the name of workers’ rights. During his 1911 sojourn in the city, David Ben-Gurion characterized Salonica as “a Jewish labor town, the only one in the world.”

The transfer of Salonica from the Ottoman Empire to the Greek nation-state during the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) transformed the city. In 1917, a fire destroyed two-thirds of downtown, leaving over 70,000 people homeless, including 52,000 mostly poor Jews. The new Greek authorities used the fire as a pretext to remake Ottoman, Jewish, “oriental” Selânik into Greek, European, “modern” Thessaloniki: They did not permit poor Jews to return to the city center, instead relegating them to shanty towns, military barracks, and housing projects. According to the manifesto, the Jewish communal institutions that administered most of the housing projects did not adequately address the residents’ own needs. Jews in the popular neighborhoods charged communal leaders with displaying a “hostile attitude toward the associations of the quarters,” and called on them to embrace the principles of mutual aid rather than charity.

The housing crisis was compounded by the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919, and then by the arrival of 100,000 Orthodox Christian refugees from Turkey in 1923. Refugees from Turkey settled in districts adjacent to those inhabited by the Jewish victims of the fire. Tensions mounted over access to scarce resources, and rising nationalism provoked violent confrontations. With no other recourse, some refugees began to occupy Jewish schools, impeding their operation—hence the manifesto’s demand that the squatters be removed “at all costs.” This demand reveals the limits of the Congress’s commitment to “solidarity,” as nationalist antagonism trumped class solidarity between these two vulnerable populations.

Jews in the popular neighborhoods organized for their rights until the bitter end. Their efforts help to explain why 39% of Salonica’s Jews voted for the Communist Party in the Greek parliamentary elections in 1926, in a dramatic repudiation of the liberal middle and upper classes in charge of both the Jewish community and the Greek government. The manifesto’s demand that new housing be allocated to Jews in the shantytown of Teneke Maale prior to its planned demolition also bore fruit: In the 1930s, the Jewish community and state authorities transferred many of the families to other districts, including one with new, modern apartment buildings.

The German occupation of the city (1941–1944) resulted in the deportation of a quarter of the city’s residents—nearly 50,000 Jews, the plurality of whom were rounded up from the neglected Jewish districts. Fewer than 2,000 survived. Those who returned discovered that the Greek state had transferred “abandoned” Jewish properties to Orthodox Christians—especially Nazi collaborators. Eventually, some of the Jewish survivors managed to reclaim their properties. While they waited, these Jews—the poor and formerly wealthy alike—slept on the benches of the only two synagogues that survived.

To read the full translation of the manifesto, click here.

Devin E. Naar is an associate professor of Jewish studies, Sephardic studies, history, and international studies at the University of Washington in Seattle and the author of Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece.