Ruins of the Gulag at Chukotka in Siberia, Russia, 2008.

Ragnar Th Sigurdsson/AlamyRefusing to Bury the Living

Emigrating from the USSR to the US meant fleeing one system of mass incarceration for another.

My elderly mother needed to go to the pharmacy, so I drove across Philadelphia to take her there. It was the first pandemic summer. Things were tense between us, and not only because she was skeptical of Covid and wouldn’t wear a mask. The police had murdered George Floyd a few weeks earlier, and my mother was spending a lot of time watching Russian news with her friends in the large Section 8 buildings that reminded me of the Soviet housing blocks I lived in as a child. They drank tea and ate zakuski and discussed Black Lives Matter’s attempt to break down the Western family structure, or whatever talking points had featured on TV-Novosti that day. She often called me afterward with stern advice on how to protect myself from the Antifa and BLM hooliganki. I’d tell her it was the police that terrified me. The National Guard had been occupying my neighborhood for two weeks, and the city police circled the area in low-flying helicopters day and night, launching gas canisters down residential streets, beating up and arresting friends and neighbors taking part in the uprising. “Eginachka,” she’d respond coldly, “to stay out of trouble, stay inside and mind your own business.”

It took about 45 minutes to get from my house in West Philly to my mother’s neighborhood on the northeast side of the city. We drove down Bustleton Avenue past Russian grocery stores and banquet halls and Blue Lives Matter flags. I waited for her to lecture me about the rioters she’d been watching on television, but this time she wanted to talk about Derek Chauvin instead. The video of the officer kneeling on George Floyd’s neck was playing repeatedly on Russian news channels and she couldn’t get the image out of her head. “The sadist,” she hissed in Russian through clenched teeth. “The whole time, you can see the pleasure in his eyes. He was displaying his force to the world.” Her body emanated waves of charged energy; the skin between past and present worlds had become suddenly porous. The police terrify her too. Our fear is where we come together; our response to that fear is where we often come bitterly apart.

My mother knows viscerally what it means to be on the receiving end of state violence. She was born in the Karaganda Gulag, a Soviet prison camp that encompassed a territory roughly the size and shape of France. Named for the steppe region in the newly formed Soviet republic of Kazakhstan where it was located, Karaganda was one of the largest camps in the USSR’s vast Gulag archipelago. During its years of operation from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s, cattle cars brought prisoners from as far away as Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Siberia to the camp, where they extracted mineral resources, felled trees, and did other kinds of mining and agricultural work. Nearly one million prisoners passed through Karaganda, a massive nesting doll of internment: ethnic and religious minorities, “enemies of the state,” inmates arrested for more traditional crimes like murder and theft. It’s unclear how many perished there; the dead were not carefully accounted for.

My grandmother Rahil Soloveichyik, a Polish Jew from a famous rabbinic dynasty, was among the many Jews imprisoned by the Soviet Union in 1938. She escaped the Nazi advance by seeking asylum in the USSR only to be swept up in the purges of Stalin’s Great Terror. In the early days of her internment at Karaganda, my grandmother was tasked with digging mass graves for those who did not survive the arduous journey. Among a pile of dead, the family legend goes, she noticed a body that was still fighting for life. The man she saved, an Estonian peasant who had resisted the collectivization of his family farm and was branded a kulak, would become my grandfather. I know little about his family besides the fact that they were Christian farmers, and likely as antisemitic as their neighbors. But life inside the Gulag made for unorthodox alliances. My mother was born in the camp and lived there with her parents until 1947, when they were released. She was nine years old.

In the early days of her internment at Karaganda, my grandmother was tasked with digging mass graves for those who did not survive the arduous journey. Among a pile of dead, the family legend goes, she noticed a body that was still fighting for life. The man she saved would become my grandfather.

The family lived in the grip of the Gulag long after their release, hiding their history of imprisonment as well as their Jewishness. My mother would go on to marry a Soviet police officer, my father, hoping to secure her standing in the USSR; he divorced her when he learned of her family’s internment because it compromised his professional ambitions. My grandmother never willingly welcomed a man in uniform into her home and never forgave my mother for bringing one in. Our emigration to America in 1990 was supposed to release us from this stigma. We were told that once we were granted asylum, the hearth of freedom and capital would be our home—that is, as long as we stayed out of trouble.

This cautionary note, the fine print of our welcome, has structured our lives here over the course of an endless march through immigration bureaucracies that has led, for some family members, to deportation facilities or juvenile detention centers. It must be particularly terrifying for my mother, who knows how easy it is to be roped into trouble by fact of birth or circumstance. Her terror has led her to radically different responses at different times: sometimes, pitying compassion for those victimized by the state, who appear to her like “cattle to the slaughter”; other times, contempt for people in our extended family or strangers on the news who “should have known better.” But regardless of the day, for her and the Russian émigrés in her milieu, there is no romance around policing. They know the police exist to protect a formal power structure—select people and their property—and that prisons exist to contain those who have been excluded from this social contract. The goal is to stay on the protected side at all costs. For the conservative writers in the Anglo-American world who have produced a voluminous body of literature about Stalin’s camps, the Soviet police state emblematizes the unique tyranny of the Eastern Bloc, offering evidence for Communism’s inherent evil and a trump card against criticism of capitalism’s blood-soaked wreckage. Robert Conquest, the British historian considered by many to be the preeminent English-language scholar of the Soviet Union, wrote in Reflections of a Ravaged Century that “at a more basic level, the blemishes on the Western body societal, however bad, in a broader comparison could be seen as unpleasant and visible afflictions of the skin, and not, as with Soviet society, cancers of the vital organs.” My mother and I have been presented with this tale of communist rot and capitalism’s sturdy foundations ever since we arrived in Philadelphia in 1990 as refugees. It always goes unmentioned that, in the period since World War II, the US has constructed the largest police force and prison system in the world since Stalin’s Soviet Union.

Long before I knew this history—before I understood that, for all their ideological divergence, the USSR and the US alike determined in the 20th century that sprawling prison systems could be used to solve their social and economic problems—I felt the truth of this continuity in my own family story: For almost a century, every generation of my family has seen someone caged, whether in the USSR, the US, or post-Soviet Russia. Despite the power of the myth of American freedom we’ve been sold, it’s clear to me that carceral punishment is at the heart of both the system we fled, and the system that caught us on the other side.

Critics of the American penal system have long drawn comparisons between America’s prisons and the Gulags of the USSR, two leading prototypes in the continuously expanding global systems of policing that have dominated the 20th and 21st centuries. Just looking at the numbers side by side is illuminating. “By 1953, under Joseph Stalin, 2.6 million people were locked up in the Gulag and over 3 million more were forcibly resettled—a total of around 3 percent of the population kept under state control,” the sociologist Stuart Schrader writes in his essay “The Making of the American Gulag.” “Today 2.3 million people are locked up in the United States, and an additional 4.5 million are on parole or probation, for a total of around 2 percent of the population under state control.” Even accounting for debate among historians over exactly how many people served time in the Gulags—some place the numbers higher—Schrader’s comparison puts the ever-growing US carceral system in gruesome company. But the connections between these two systems go much deeper. The genealogies of each stretch back centuries and are rooted in the shared imperial structures for the containment and genocide of populations deemed threatening or useless to the state. Each developed in response to the central political and economic question that defines all nation-state projects: What is to be done with the people and the land? Who belongs and who does not?

Emma Goldman was disturbed by the extent of the early Soviet carceral system. Recounting a conversation with Lenin about what she had witnessed, Goldman wrote, “Those who served his plans were right, the others could not be tolerated.”

In the case of the USSR, the Gulag—an acronym for Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerie, or Central Camp Administration—first took its modern form under Lenin, who reshaped the Russian imperial prison system to suit the Soviet Union’s needs almost immediately after seizing power in 1917. The Bolsheviks incarcerated class enemies, including the aristocrats from whom they had seized power, as well as a spectrum of political allies who began to question their methods of rule. Emma Goldman, touring the country after decades in the US, was disturbed by the extent of the early Soviet carceral system and described it in her 1923 book My Disillusionment in Russia; recounting a conversation with Lenin about what she had witnessed, Goldman wrote, “Those who served his plans were right, the others could not be tolerated.” Stalin greatly expanded the Gulag system, creating a vast archipelago of jails, prisons, and labor camps that ranged from the Baltics to the Caucasus and to the border with China. The Bolshevik party often encountered resistance across the vast multiethnic and multireligious Russian empire as it attempted to reshape the ethnic and political boundaries of its new socialist states. Under Stalin, the Gulags served the dual purpose of quelling defiance and clearing land by warehousing masses of people. These methods not only suppressed unrest but created a labor pool of displaced people who could be forced to extract resources from mineral-rich regions and produce the goods necessary for Soviet industrialization and the war economy. The system hit its apex during World War II, when the Soviet Union solidified its grip on its far-flung territories and its power on the world stage, and declined following Stalin’s death in 1953.

The contemporary US prison system developed around the time the Gulag system was breaking down. Policing in the US has roots as old as the first American settler colonies, but what contemporary abolitionists call the prison industrial complex, or PIC, is a 20th-century phenomenon shaped by America’s rise to global superpower status after World War II. As in the Soviet Union, mass incarceration developed as a state response to a political and economic crisis; not for nothing did the geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore call her monumental study of the California prison system Golden Gulag. Gilmore treats California as a paradigmatic illustration of the postwar prison boom in the US—which accelerated in the 1980s—in much the same way that Siberia or Karaganda became paradigmatic illustrations of Stalin’s prison boom. In her classic account, the crisis began when industrial jobs created by World War II disappeared during peacetime. These jobs had bolstered the New Deal welfare state, and when they ceased to exist, vast numbers of workers and huge swaths of land became “surplus,” unusable from the perspective of business interests and the state. Prisons, then, served the dual purpose of warehousing the newly jobless poor, particularly Black and brown workers who existed on the margins of the New Deal order to begin with, and creating a function for land and facilities sitting idle across California. The PIC’s remarkable growth in this period created profit for parties ranging from universities to small-town landlords to bond market power brokers to police unions. As Gilmore shows, investing in prisons was a gold rush. The process was copied in various forms across the country, cementing the PIC’s status as a new pillar of the American economy.

When my mother and I arrived in the US, we were slotted into a social matrix in which infrastructures of scarcity, punishment, and policing were organized by racial histories we did not know and attached to class norms we did not recognize. In the Soviet Union we were first and foremost classified as Jews, which meant second-class citizenship with structural limitations to belonging and assimilation. In the US, on the other hand, we were declared white—but in exchange for the privileges that went with this status, we were asked to serve as minor characters in a grand story about the incommensurable differences between Soviet tyranny and American freedom. The US, we were told, was a fair society built on equality and maintained by law and order. Our poverty was a temporary embarrassment, and the poverty of others was their own moral failing. We received lectures on how, unlike in the USSR, industrial facilities of punishment did not exist in the US. Of course there were jails and police, the proselytizers would explain; after all, there was no blotting out the evil inherent in human nature. The state’s role was to provide us with an opportunity to move up the ladder. Our role was to keep quiet and keep ascending—to stay out of trouble, stay inside, and mind our own business.

The US, we were told, was a fair society built on equality and maintained by law and order. Our poverty was a temporary embarrassment, and the poverty of others was their own moral failing.

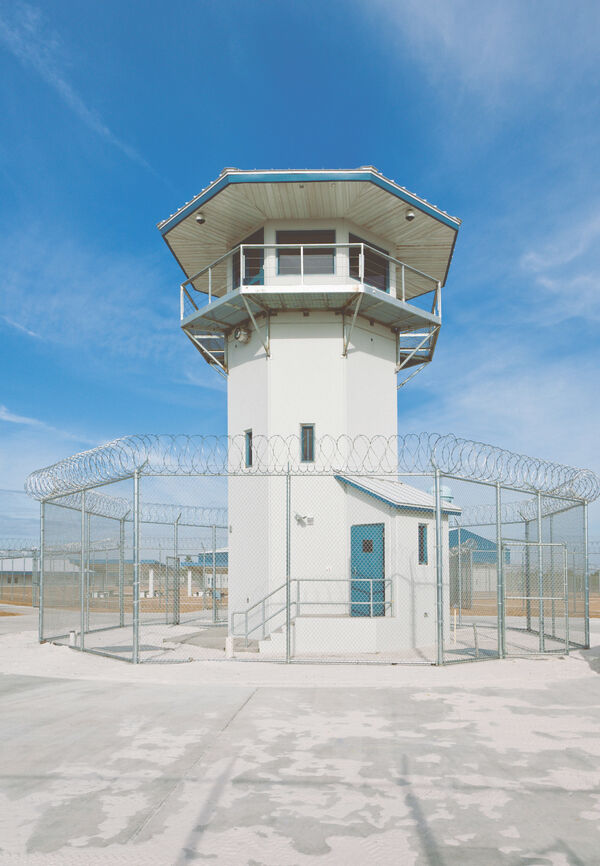

Guard tower at a correctional institution in Central Florida, 2009.

The Gulag Museum at Perm, Russia.

We were also, crucially, asked to enrich this national myth with stories about our own suffering in the Soviet Union. People with all kinds of ideological investments, from my teachers to our rabbis to our lawyers to Russian-speaking Jews further along in the assimilation process, used these stories to reify a Cold War narrative of a colorblind, classless America. On one memorable occasion when I was a child, the liberal American Jewish doctor who employed my mother as a live-in housekeeper peppered her over the dinner table with questions about what she had survived. When she finished he leaned toward me with an air of paternalistic warmth and confidently declared, “Only in America will you be safe and prosper.”

The American immigration system itself used us to make a similar point. Our asylum process stretched on for almost a decade after we arrived in the US until finally, in 1999, our stay of deportation was granted in Texas, where we had moved a few years earlier. It was not a good time and place to be an immigrant. Border detention facilities were beginning their monstrous expansion, the Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) were soon to splinter into a new web of agencies (including, most notoriously, ICE), and anti-immigrant rhetoric was pervasive. The judge who presided over our hearing was notorious for denying asylum status to the refugees whose cases he oversaw, mostly migrants from Latin America fleeing the violence occasioned by decades of US anti-communist counterinsurgency. To our benefit, however, we were not fleeing US-trained death squads in Central America but state communism’s own internal failures. At our hearing, my mother—small, fair-skinned, and charismatic—recounted through a legal interpreter the story of her childhood in the Gulag, my grandmother’s tortures and losses under both Stalin and Hitler, their hardships after internment. Before she could finish her remarks, the judge interrupted her to grant us asylum.

Yet for all these assurances of our welcome in America, the process of obtaining political asylum and citizenship continually entangled us with policing institutions from the INS to the FBI. Throughout our immigration proceedings, these institutions controlled our access to everything we needed to survive: health care, education, employment. The material conditions of receiving asylum were long, costly, and often humiliating. We had background checks and biometrics done every two years. Each legal step had a price—lawyers’ fees, government fees, processing fees—adding up to more than my mother, who could barely speak English and was supporting us on minimum wage jobs, could save or borrow. Once, as a teenager, I forgot to renew my employment authorization card and lost my job as a museum security guard; it took months to save enough money to pay the $95 to get my card back. Over the years, various relatives slipped from the rungs of the ladder and into jails, prisons, and deportation holding centers; I dropped out of high school and came close to joining them. Poverty kept us tethered to the American nightmare even as whiteness enabled our foothold in the American dream.

The supposedly divergent roads to citizenship and to incarceration began to run together in my mind. It was hard to tell the difference between the fees for my employment authorization card and the legal fees and daily costs of living that one family member accrued while in a Texas deportation facility. I began to wonder where all the money was going. Who benefited from the costs we had to pay at seemingly every step and misstep? I thought of the stories told in the émigré community about the ubiquitous corruption of the Soviet police state. I thought about my father, who as a police officer had access to goods only available on the black market; he often came home with cash or a new car or an object that cost much more than his official monthly earnings. It seemed that the incommensurable gap between the Soviet police state and the benevolence of American law and order was an illusion, that objects had been rearranged and images distorted, but the overarching carceral structures remained the same.

We could say none of this aloud without appearing ungracious to our benevolent hosts: Because our downward trajectory did not figure into an immigrant bootstrap narrative, throughout my childhood and well into my twenties we were regarded as cautionary tales, an afterschool special of Soviet Jewish immigrants gone wrong. Would we have been safer or more secure if we had stayed in the USSR, which collapsed a year after we left? It doesn’t seem likely. The massive carceral systems pioneered by the Soviet Union and the United States are global now, with the US taking the helm in innovating police practices around the world. In Uzbekistan, where my father and his new family remained for a few years after the former Soviet state became an independent country, new police forces were hired to administer and update a prison system inherited directly from the old regime. Some former officers were simply rehired under a new flag. My father, however, was not. No longer a policeman, he was granted no special favors in this new social order marked by brutal austerity and severe inflation, and like many men of his generation, he drank himself to death. As his trajectory suggests, enforcers of the carceral system are not immune to becoming surplus themselves once they are no longer useful. And as usual, the bitter irony has not been lost on my family. I remember an exchange I had a few years ago with my half-brother shortly before he finished a seven-year prison sentence outside of Moscow. “Well Eginachka,” he wrote, “our father was a cop and I am a prisoner. Life is a funny thing.”

I see my grandmother’s choice to fight for the life of a stranger in the depths of a mass burial pit—her refusal to bury the living—as a compass for abolition.

In the last few years, I’ve noticed that it isn’t just the right that finds the story of the Gulag useful. Within the contemporary US left, apologists often start with a joke about what will happen to the perpetrators of capitalist atrocities “when we’re in charge of the Gulag.” But then—at least when I’m around, as an awkward reminder of the history of state socialism in the USSR—the conversation turns serious. How would counterrevolutionary forces be managed, if not through mass incarceration? How could state power be maintained, if not through a system of policing? Don’t we need to consider the jobs of prison guards alongside the lives of prisoners?

The people who make these arguments say abolitionists are naive for imagining that any society can function without prisons. And I think they are naive—and terrifying—in their naked desire to power a system of punishment they do not seem to understand. Revolutionary thinkers from Goldman to Gilmore have been guided by a different premise—that our struggle is not simply finding means to control the existing systems of power but in the daily struggle of caring for one another in the midst of seemingly endless cruelty. It is not about contending with a fixed idea of human relations, but about imagining another way entirely. The truth is, I myself struggle to believe and behave as if things could be different. But then I think of my grandmother, who was no optimist. I see her choice to fight for the life of a stranger in the depths of a mass burial pit—her refusal to bury the living—as a compass for abolition. As the child of that fateful choice, my mother offers a reminder that we make and remake such decisions daily and often in contradictory ways. The day she recognized Derek Chauvin as a figure of the state’s white supremacist bloodlust was a day she refused complicity. This recognition is not absolution, but it is an opening.

Egina Manachova is a Philadelphia-based freelance writer. She was born in Tashkent, raised in Texas, and has called the Mid-Atlantic home for over a decade. She loves seltzer and a sharp wit.