Rediscovering a Pathbreaking Queer Jewish Writer

A conversation with historian Jonathan Ned Katz on the life of Eve Adams.

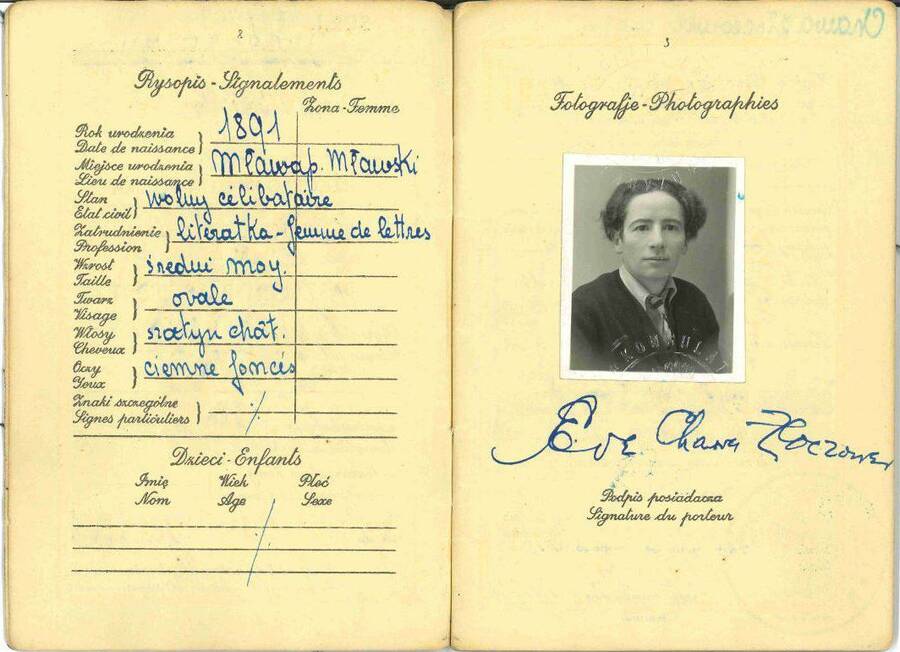

For nearly two years in the mid-1920s, at a site on Greenwich Village’s MacDougal Street that is now a pizza joint favored by NYU students, Eve’s Hangout once stood. There, as Julie Scelfo writes in The Women Who Made New York, patrons “staked out a space for sexual free-thinking.” The eponymous proprietor had arrived in the United States in 1912 at age 20 from her hometown of Mława, Poland, entering the country as Ewa Zloczower. By the time she opened her New York tearoom in 1926, she was Eve Adams, and she had spent her time in the US working in a garment factory, traveling the country selling leftist periodicals, co-running a tearoom in Chicago, and hanging out with anarchists like Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, and Ben Reitman (who wrote about her in his unpublished “Outcast Narratives”). She had also written a pamphlet of stories called Lesbian Love, featuring character sketches of some two dozen women.

The Department of Justice opened a file on Eve as early as 1919, searching her room in Connecticut (where she was selling magazines) and accusing her of being an agitator for the International Workers of the World (IWW). She was finally arrested in a sting operation in 1926 on charges of selling an “obscene” book and of “acting insultingly toward a policewoman” with an “alleged sex attempt.” Convicted of both, she was sentenced to 18 months in prison. While Eve was incarcerated, the state began deportation proceedings against her, and despite her ardent plea to remain in the United States—“I love this country with my whole heart and soul,” she told the judge—she was sent back to Poland after her prison term ended. Working as a nanny, a Hebrew teacher, and a seller of books outlawed in the US to American tourists, she made her way to Paris, then to the south of France as Hitler advanced. But she could not outrun the Nazis; she perished at Auschwitz.

While some basic facts—and many fictions—about this radical queer Jewish writer have floated around the internet for years, Jonathan Ned Katz’s new biography, The Daring Life and Dangerous Times of Eve Adams, is the first book-length attempt to fill out the details of her story and place it in its political and cultural context—and to make available the full text of Lesbian Love. An independent scholar and one of the creators or LGTBQ Studies, Katz is the author of Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A.(1976), Gay/Lesbian Almanac: A New Documentary (1983), and The Invention of Heterosexuality (1995), among other groundbreaking books. Recently, we sat down to discuss this latest project, which recovers Adams’s life amid a burgeoning queer culture and a repressive, anti-immigrant, antisemitic, and homophobic state. Our conversation below has been edited and condensed. It originally appeared in yesterday’s email newsletter, to which you can subscribe here.

Alisa Solomon: Jonathan, you’ve been a pioneering LGBTQ historian—“foraging for our lost history,” as you put it in a lovely phrase—for more than 50 years. Yet you hadn’t come across Eve Adams until recently. Why do you think she was lost to us? And how did you find her?

Jonathan Ned Katz: Her book is very, very rare. Yale was the only institution that had a copy, and it was stolen in 1998. It was when I read a reference to her in Scelfo’s The Women Who Made New York in 2016 that I got very interested. This book led me to Barbara Kahn, a playwright who wrote a couple of plays based on research about Eve. I give her credit for beginning to create interest in Eve.

AS: How did you get your hands on a copy of Lesbian Love?

JNK: Because Barbara had put on plays based on Eve’s life, she was contacted by a woman who had found a copy by chance. I contacted her and tried to gain her confidence over many months, and it worked out. It was amazing to get ahold of this rare book that no scholar had looked at, except maybe the person who stole the book from Yale.

The plays also led to people writing to Barbara. She had the help of a gay man who was an archivist. He found the deportation hearing testimony—one of the main documents in which we hear Eve’s voice, which is so important.

AS: How would you characterize her voice?

JNK: Her English isn’t perfect, which I love. It makes her real to me. I start the book with her deportation hearing because I wanted to have her voice come in right at the start and let her be heard again. In the hearing, she wouldn’t say who helped her when asked—she wouldn’t inform on others.

AS: Why was she tried at all? Why did the US government want to get rid of her, even to the point of setting her up with police entrapment, and how did her queerness figure into this?

JNK: They had gotten rid of the Wobblies [the IWW] a little earlier. J. Edgar Hoover, that monster, also played a role in that. Eve was one of many—they had already deported Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. They were killing people or putting them in jail or deporting them and otherwise defanging the left. They used her queerness to get rid of her, but they were on to her because she hung out with Emma Goldman and was going around the country selling radical periodicals. That was the extent of her radical activities, and in retrospect it looks like a huge violation of her right to free speech, the free press, due process—all kinds of civil liberties. They got her on the “obscene” book and her coming on to a policewoman—“disorderly conduct.”

AS: As you discuss in the book, they were also cracking down on all kinds of allegedly “obscene” publications and performances, like the plays The Captive, Mae West’s Sex, and the Yiddish play God of Vengeance (once it was translated and performed in English). But this time was also, as you write, “sex o’clock” in America. What was the context for sexual exploration and expression during that era?

JNK: The Bohemian set was pioneering free love: not necessarily married and not necessarily monogamous. By experimenting with sexuality apart from procreation, as one of the pleasures of life, they were going against very fundamental moral values of the time, making a huge break with the dominant norm of middle-class propriety. Eve was moving in this set. If sex is non-procreative, what’s the difference between heterosexual and homosexual?

AS: What surprised you when you first read Lesbian Love?

JNK: I was delighted that it has a section called “How I Found Myself”—I think it’s the best-written section and the most emotionally evocative. It’s Eve writing about her first sexual experience with a woman and how beautiful and meaningful and even troubling it was while it was happening. That was thrilling. As I reread the collection, I realized a lot of the other characters sound like Eve, too. She was a member of the Ladies’ Waist Makers’ Union and there’s a character, Jimmie, who is also a member of that union, and goes to a hotel in the Pennsylvania countryside—that was probably Unity House in Bushkill, which was owned by two locals of the union and was made up of radical Jewish women garment workers. Eve was a working-class person, and that’s important, because it’s really hard to recover working-class history, especially lesbian working-class history.

AS: Jimmie, like a lot of Eve’s characters, seems to align more with what we might nowadays call trans or nonbinary or gender nonconforming identity than with a lesbian sexual orientation. Is that just because of how our ideas have changed over time, or Eve’s lack of exposure to notions of sexuality, or . . . ?

JNK: The dominant idea of same-sex sex at that time was sexual “inversion”—that you’ve inverted the norm of male/female, either by having same-sex sex or by performing in some way as the “opposite” sex with clothes or a walk or cutting your hair. At one point in her book, Eve refers to a butch character as a lesbian, but doesn’t refer to her fem partner that way.

AS: When she was back in Europe, Eve did not become part of the famous circle of lesbians in France—Gertrude Stein, Natalie Barney. You suggest that it has to do with her being an out Jew, her saying “lesbian” out loud, and, maybe most of all, her being working-class.

JNK: Yeah. She had to really struggle to make a living in Paris by selling modernist books along with silly porn. I thought she might have been friends with Margaret Anderson [the co-editor of The Little Review, which published an excerpt of James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1920, leading to a conviction for obscenity]. Anderson also knew Emma Goldman and went to Paris around the same time as Eve. But I didn’t find any evidence—just a hint: When the FBI looked at Eve’s papers, they found the name Margaret Anderson on one of the subscription lists for radical periodicals. Some lesbian researchers in Paris are looking for other evidence there. There are a lot of mysteries and missing pieces to this story. Part of what I’m hoping the book will do is get people to do more research and find things that I wasn’t able to find. I put a list of questions that researchers could take up on outhistory.org, the website that I founded.

AS: It seems like you developed an almost personal relationship with Eve. You note how intimate the image of her fingerprints feels to you. In the epilogue, you write about how working on her story made the Holocaust concrete to you for the first time, because now you really knew someone who was murdered by the Nazis. What created such a strong sense of connection with someone you never met?

JNK: She just became a friend over the years I worked on the book. Her 1941 passport photo, which she had taken when she was yearning to come back to the US, looks just like you and me and everybody else: She is dressed casually, and the clothes aren’t any different from what people are wearing now. She seems very contemporary. And I was alive in 1943 when she was killed. I grew up in Greenwich Village, so I walked by the place where she had her café many times.

Also, I had a very important relationship with a therapist who was a Holocaust survivor, who told stories about escaping from Nazi Germany as a 13-year-old. He’d have been very proud of my doing this. He wanted me to be more Jewish, but I couldn’t accommodate that. My father was a Communist. My mother told me, “Your father and I are atheists.”

AS: How was doing research on this project different from when you started working on queer history more than 50 years ago?

JNK: Completely, utterly different. I used to have maybe 5,000 three-by-five file cards. Each one had a notation about a source for queer history. I had photocopied each existing bibliography on homosexuality—medical ones, a newspaper one, and so on. I cut them up and pasted the entries on cards and put them in chronological order. This time I barely left my seat in my room. I emailed libraries and got things that way. I sat at my computer and spoke to Eran Zahavy in Israel, whose grandfather was Eve’s brother and whose grandfather tasked him as a young boy with finding out what happened to Eve in World War II. He took it upon himself to try to find the family of Eve’s companion, Hella Olstein. He found them in Switzerland, and they said, “Oh yeah, we have a file of letters from Hella that includes notes from Eve and some letters from Eve. Oh, and Eve left her old passport with Hella’s brother.” Those are the letters that express their growing fear of the tightening noose of the Nazis in occupied France, where they were living. So that’s a good example of the wonderful collective character of this research process.

The other wonderful thing is that these families, instead of burning the letters of their queer relatives when they found out somebody was going to make an inquiry, were very cooperative. That’s a whole new situation. That’s not what families did in the old days.

Alisa Solomon is the author of Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof, and of Re-Dressing the Canon: Essays on Theater and Gender and a professor at the Columbia School of Journalism.