Reading Baldwin After Kanye

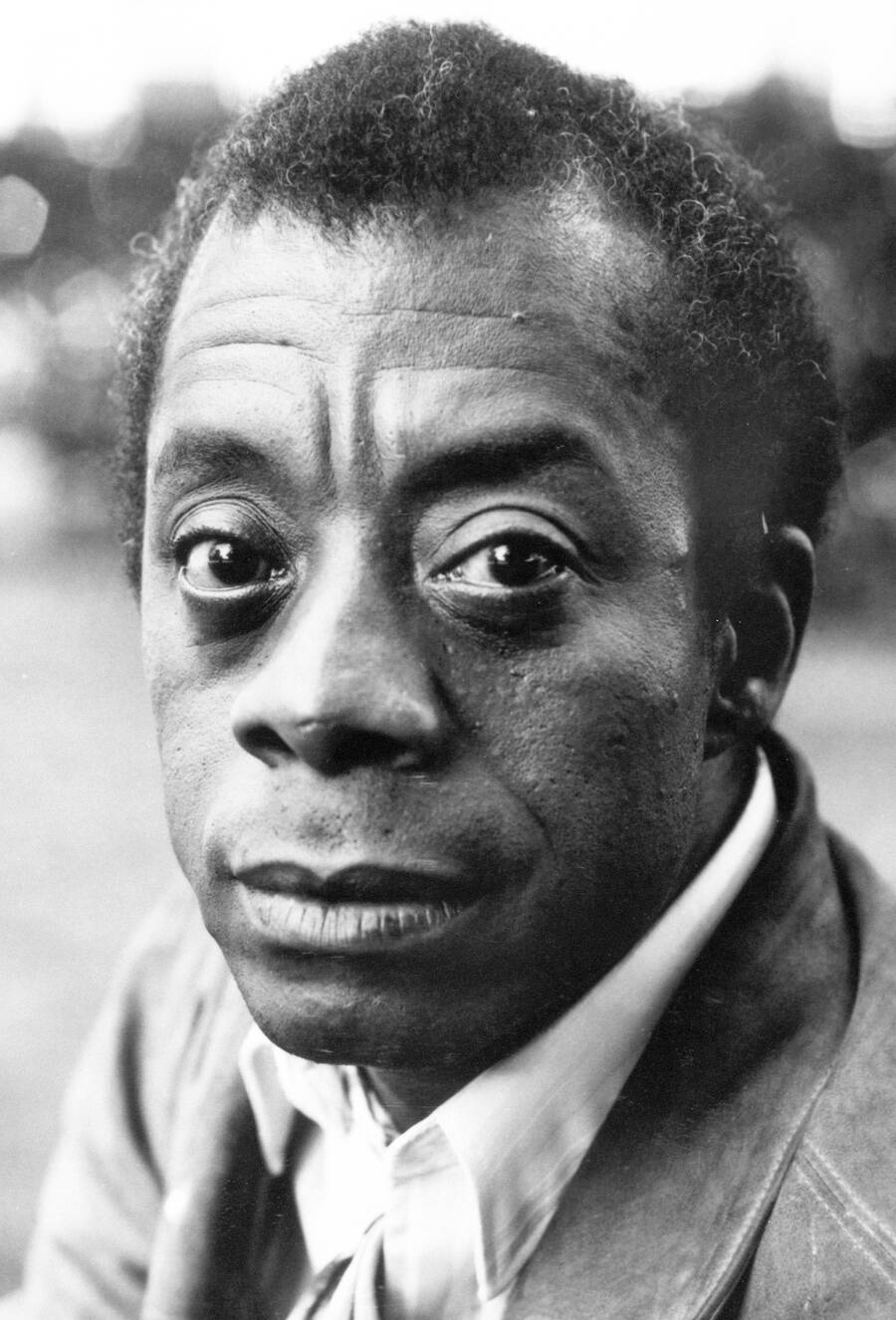

A conversation about James Baldwin’s 1967 essay, “Negroes are Anti-Semitic Because They are Anti-White.”

James Baldwin

Last fall, a series of incidents stoked the flames of a perennial conversation about the relationship between Jews and non-Jewish Black people in the US. In October 2022, Ye (the rapper and fashion designer formerly known as Kanye West) tweeted that he was going to go “death con 3 ON JEWISH PEOPLE” to his 30 million followers. He followed his tweet—which riffed on DEFCON, the acronym that refers to a military state of alert—with a series of antisemitic tirades. Later that month, NBA superstar Kyrie Irving tweeted a link to a documentary that claimed to show that Black Americans are the only true descendants of the biblical Israelites.

These events provoked a knotty set of questions: What were we to make of high-profile celebrities embracing such noxious views? Why were there immediate material repercussions for Ye’s antisemitism—Adidas cut ties with the rapper at a projected cost of over a billion dollars—when his many anti-Black statements (wearing a White Lives Matter t-shirt, calling slavery a “choice”) received little pushback from his corporate partners? And what does it mean that both of these celebrities are Black?

The discourse around these events soon fell into familiar territory, with many quick to call the whole affair the latest flare-up of “Black antisemitism”—a phrase that emerged in the 1960s amid debates over the role of Jews in the civil rights movement and the growth of Black power. In responding to this argument, progressives generally question the existence of “Black antisemitism” as a unique phenomenon, citing James Baldwin’s 1967 essay “Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White.” The essay is often reduced to its title, which suggests that antisemitism in Black communities is best understood as an expression of hatred of white supremacy, thereby dismissing claims of difference between Jews and other white people in a Black/white binary. But as is characteristic of his writing, Baldwin’s argument is subtler and more ambiguous than any shorthand can capture.

Baldwin penned the essay following his resignation from the advisory board of the Black nationalist magazine The Liberator in response to a series of articles, “Semitism in the Black Ghetto,” which argued that Jews were especially responsible for the terrible conditions in Harlem. Explaining his resignation in the Black cultural journal Freedomways, Baldwin wrote that “it is distinctly unhelpful, and immoral, to blame Harlem on the Jew.” In the wake of his resignation, The New York Times invited Baldwin to “discuss the phenomenon of anti-Semitism among Negroes.”

In his essay for The Times, Baldwin moved from local reflections on the material conditions of Harlem to a consideration of the global dynamics of Christian imperialism, arguing that any discussion of “Black antisemitism” must begin from a consideration of the nature of whiteness. In tension with a good deal of contemporary debate, Baldwin suggests that both Jewish and Black Americans can fall prey to the pathologies of whiteness: Jewish people can throw off their memory of oppression and become the exploiters, while Black Americans can adopt the antisemitic attitudes of a colonizing white Christianity. This analysis pushes against the simplicity of the essay’s title, pointing at a certain degree of specificity regarding both Black expressions of antisemitism and how Jews inhabit whiteness.

Since last fall, the controversies with Ye and Irving have been followed by others. Most recently, the rapper Noname, who has built a reputation for social consciousness, came under fire for a verse on her album by Jay Electronica, whose lyrics often reference the antisemitic teachings of Louis Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam. In response to the controversy, Noname wrote on Instagram, “no, i’m not antisemitic . . . i’m against white supremacy which is a global system that privileges people who identify as white.” To help us reflect on these recurrent incidents, we thought it would be helpful to look closely at Baldwin’s touchstone piece. To do so, we brought together four writers and thinkers who have thought deeply on these matters. Marc Lamont Hill is an author and a professor at CUNY Graduate Center, who was himself a figure in one such “Black–Jewish” flashpoint, when he was fired from his position at CNN after accusations that a UN speech in which he referred to a “free Palestine from the river to the sea” was antisemitic. nyle fort teaches African American studies at Columbia University and is a faith-based organizer with the racial justice group Dream Defenders. Chanda Prescod-Weinstein is an author and a professor of physics and women’s and gender studies at the University of New Hampshire, and the chair of Reconstructing Judaism’s Jews of Color and Allies Advisory Group. Ben Ratskoff is a professor at Hebrew Union College; his current research explores how Black American intellectuals understood the persecution of Jews in Europe. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

—Daniel May

Daniel May: Throughout this essay, Baldwin argues that for very material reasons Jews have come to be the face of white supremacy for large numbers of Black Americans. I’m curious what you make of the link Baldwin draws between Jewishness and whiteness—and how you see that link as relevant to the controversies of last fall?

Ben Ratskoff: In Baldwin’s writing—especially his early writing—we see a struggle to triangulate three categories of Jew that exist in his imagination and his experience. There are the Jews from the Bible that he heard about in his father’s church, those almost mythical characters of suffering and exile with whom Black churchgoers often identify. Then there are the leftist Jewish intellectuals and artists he met in high school, who were his lifelong companions and collaborators. And finally, there are the white Jews engaged in exploitative behavior in Harlem.

The real Jews of his experience would include his high school friends. It would also include, we can assume, Black Jews in Harlem. But he’s not interested in talking about those Jews in this essay. He’s interested in the figure of “the Jew”—a figure who is understood as white, and who embodies the contradictions of white Jewishness.

Marc Lamont Hill: I can’t imagine that Baldwin wasn’t aware of the complexities of Black Jewish identity. There were Black Caribbean Jews and Commandment Keepers[1] in Harlem his entire life. But Black Jews aren’t the people who are leaving at night, they aren’t the landlords. So, central to his critique is “the Jew” as it’s constructed in the public imagination, which is correlated with the capacity to assimilate into whiteness.

Chris Rock had a bit years ago: “Black people don’t hate Jews, Black people hate white people.” To me that would have been a better title for Baldwin’s essay, because I think that’s what he’s actually saying here. If it wasn’t Jews but Koreans who were the landlords in Harlem, would we have felt any differently about them? Probably not.

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein: We know the answer to that question. We’ve seen it play out in Los Angeles.[2]

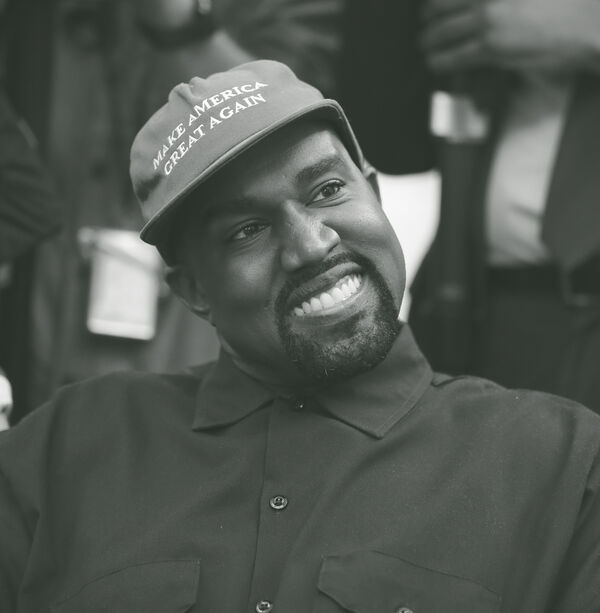

Ye in a “Make America Great Again”

hat during a meeting with Donald Trump, October 11th, 2018.

MLH: Exactly! That’s why I’m not convinced that Baldwin is actually talking about antisemitism—the hatred of Jewish people for being Jewish—within the Black community. Rather, he’s critiquing a set of problematic and exploitative relationships that happen to include, in this particular case, Blacks and Jews.

Consider the Kanye West moment, for example. When Kanye was describing exploitative relationships in the music industry, I was like, “That’s not Jews! That’s just music execs!” When [the rapper and music executive] Diddy gave people record deals, he offered the same shitty deals that everybody else did. This is an unavoidable consequence of capitalism. Unfortunately, antisemitic tropes tell us that “all the execs are Jews” and that “all Jews are inclined toward economic exploitation.” Unfortunately, Kanye seems to have bought into those ugly antisemitic myths. By descending into antisemitism, Kanye cheapened his analysis and squandered an opportunity to critically interrogate the ugly underside of the music business. But Baldwin describes a far more nuanced dynamic than what we see with Kanye. He is able to hold space for Black critique and Black rage, without painting Black people as collectively antisemitic, which is what so often happens in the discourse.

“Baldwin is able to hold space for Black critique and Black rage, without painting Black people as collectively antisemitic.”

DM: What you’re laying out, it seems to me, is one of the ways that this essay has been deployed in conversations about so-called Black antisemitism, particularly on the left—which is to say that “Black antisemitism” is not actually antisemitism, it’s anti-racism. But as you note, Marc, it’s not as though Kanye stopped at the capitalist critique. And the essay isn’t called “Negroes are not antisemitic. They’re anti-white.” On the contrary, it seems to me that Baldwin is suggesting that Jews are a target of Black animosity for specific historical and structural reasons.

CPW: One thing I find powerful is how clearly Baldwin is able to articulate that the problem at the end of the day remains white supremacy. There are certainly non-Jewish Black people who are antisemitic, but Baldwin differentiates this from the structural levers of violent antisemitism, which remains within European Christian antisemitism. To the extent that non-Jewish Black people have antisemitic views—for example, buying into stereotypes about Jews handling money or being uniquely power-seeking—that’s where they’ve learned them: from white, Christian perceptions of Jews.

nyle fort: I also find the structural argument valuable. In a context where naming the power of Jewish elites can sound indistinguishable from a conspiracy theory, Baldwin says it like it is: These are the conditions that Black people in Harlem—including himself—experienced, which means that antisemitism is not something that just menaces the minds of individuals; it’s rooted in material realities.

CPW: One thing Baldwin doesn’t talk about is Jews and class. The Jews he engages with are professionalized people—store owners, businesspeople, teachers. That is not at all the Jewish community where my grandmother Selma grew up in 1930s Brooklyn, just one generation before Baldwin wrote this piece. We’re talking about people who worked in factories, who lived in tenements. And of course, working-class Jews existed in Baldwin’s time, too—but they aren’t part of the analysis.

MLH: Part of his analysis rests on the idea that Jews have had the same extractive relationships in our community that other white people have had. But if he’d considered your grandmother’s neighborhood, he might have seen the way that American Jews in that moment remained ghettoized, marginalized, and marked as distinct. So does Baldwin overstate the extent to which Jews became white?

CPW: This is a question I ask myself a lot. It’s complicated, because there was never a single American Jewish community. My understanding is that there was a point in time when some Sephardim—like the ones who came in the 18th and 19th centuries, some of whom participated in the slave trade—were white, while Eastern European Jews were not necessarily white. The essay doesn’t grapple with the ways these ethnic and geographic specificities are significant for thinking about uneven racialization in Jewish communities.

And Baldwin is also writing at a kind of inflection point. My grandfather was born in Brooklyn in 1917. Yiddish was his first language. He was clearly racialized as Other. At that time, Jews—particularly the children of Russian and Eastern Bloc immigrants—were not considered white. But when he died, in 1988, he died as a white man. If we look at Baldwin’s essay as a historical document, we can see it as recording a moment where that transition is happening.

BR: I would argue that Baldwin doesn’t overstate it. I think it’s important to complicate the consensus that Jews “became” white in the postwar era. As you suggested, Chanda, with respect to Sephardic settlers, the US considered some—if not most—Jews as “free white persons” as early as the 1790 Naturalization Act.[3] Even in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Jews faced increased racial discrimination, the state often considered “the Hebrew race” as a subcategory of “the Caucasian race.” A lot of our thinking about Jewish whiteness is constrained by a binary that doesn’t allow for hierarchical differentiation within whiteness, such that there can be lesser whites, white and Other at once.

When we talk about whiteness—and this question of Jewish whiteness—we also have to ask: White from whose perspective? The state’s? Black communities’? Jewish communities’? The answers will differ. Let’s take the case of Jewish factory superintendent Leo Frank: In 1913 Atlanta, he’s falsely accused of murdering a white Christian girl. His defense and supporters mobilize all sorts of discourses about Black bestiality and stupidity to discredit the prosecution’s star witness: a Black man. Ultimately, though, Frank is lynched. While one might conclude from this incident that Jews—vulnerable to both state discrimination and extrajudicial violence—were not fully white, the Black press clearly represented Frank as white. In his essay—even in the rather polemical headline—Baldwin helps us to think about whiteness in this shifting, relational way. He reminds us that it is in fact not a contradiction that Black people in Harlem could perceive non-Black Jews as white, and that non-Black Jews could experience discrimination and violence. State discrimination, extrajudicial violence, and the social experience of racial perception do not always cohere.

“A lot of our thinking about Jewish whiteness is constrained by a binary that doesn’t allow for hierarchical differentiation within whiteness.”

MLH: That’s true, but part of Baldwin’s moral critique of American Jews is that they do have choices, and that they’re making the wrong ones. When he writes that the Jew in America “is singled out by Negroes not because he acts differently from other white men, but because he doesn’t,” his charge is not particularly subtle. He seems to be suggesting that they’ve opted into whiteness. I’m proposing that he might be overstating the level of agency that American Jews had at the time to make those choices.

BR: I agree—regardless of whether Jews are perceived socially as white, Other, or both, it doesn’t negate their agency. Though I also think Baldwin contradicts himself a bit, because he suggests that Jews are willfully playing a role and also that they were assigned this role by Christians. So how do we think about exploitative Jewish roles in the context of a larger Christian power structure? Obviously, personal disavowals of whiteness are not helpful. But individual and collective acts that betray, refuse, subvert, and abolish these roles seem both possible and necessary.

nf: That’s why the question of what we do with Baldwin’s analysis is so crucial. Baldwin once said, “I can’t be a pessimist . . . To be a pessimist means that you have agreed that human life is an academic matter.” I take that to mean, in part, that we ought to read him in the context of political education. Which is not to say this essay is a guidebook or a blueprint, but when Baldwin writes that the Jew says, “We suffered, too . . . but we came through, and so will you. In time,” I couldn’t help but think about Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”[4] Underneath all of Baldwin’s writings are questions of solidarity—not simply an assessment of what has been done, but an interrogation of how else we might act.

DM: Marc, earlier you asked if this essay would read differently if another group of people was doing the exploitation. It seems to me that Baldwin makes two moves in describing why animosity toward Jews in particular in certain Black communities would be understandable. The first is, as we’ve discussed, the material argument that Jews are the face of whiteness in these neighborhoods: They own the buildings, the department stores on 125th Street that are overcharging Black folks and not hiring them. But then, toward the end of the essay, he shifts to a psychological argument—that there’s a particular anger provoked by the ease with which Jews have assimilated into whiteness, their denial that they benefit from the privileges that come with that, and their embrace of a myth of America that is predicated on anti-Blackness. He writes: “The Jew does not realize that the credential he offers, the fact that he has been despised and slaughtered, does not increase the Negro’s understanding. It increases the Negro’s rage.” So it’s not just that they are white, it’s not just that they are in a position of power, it’s because they’re in that position as Jews.

CPW: I want to add that, on the question of agency, Baldwin goes on to say, “No one can deny that the Jew was a party to this, but it is senseless to assert that this was because of his Jewishness . . . If one blames the Jew for not having been ennobled by oppression, one is not indicting the single figure of the Jew but the entire human race . . . I know that my own oppression did not ennoble me.” It’s a bit of a read: “Y’all have all of these issues, but if we were in the same position of power, would we be any different?” Unless we shift the power structure itself, these relations will exist regardless of how we’re embodied.

“Unless we shift the power structure itself, these relations will exist regardless of how we’re embodied.”

BR: The context of the piece is important here too, as this essay came on the heels of Baldwin’s resignation from The Liberator after its publication of a series of antisemitic articles. He didn’t write the essay merely to explain alleged Black antisemitism to white readers, he wrote it in the context of a debate with Black militants, editors, and writers—offering an alternative to the analysis put forth in The Liberator and using the opportunity to question the assumption that the suffering of Jews would “ennoble” them. This is also a position that we find in some literature by Holocaust survivors—that oppression is not a school from which one graduates as a more enlightened being.

nf: He says you would have to be a romantic to be surprised by the fact that Jews are now in a position to be exploitative. As his critiques of Christianity and his critiques of the Nation of Islam in The Fire Next Time make clear: Anybody in a position of power is susceptible to becoming exploitative. I think he’s making a consistent argument—not just in this essay, but throughout his work: Your identity doesn’t determine what you think, what you might do, what you value.

CPW: But again, I think there is a question Baldwin is raising here about how Black people perceive Jewish perspectives on Black suffering that is specifically about their Jewishness. nyle, I love that you brought up “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”; Baldwin is castigating Jews who “arrived here out of the same effort the American Negro is making: they wanted to live, and not tomorrow, but today,” but who are now asking “the Negro to wait.” On the one hand, as you said, nyle, he’s universalizing. And on the other, he’s referring to the specific parallels in experience with oppression. We’re having this conversation right after Passover, when Jews sit around a table and say, “We were slaves in Egypt.” It’s important to note that Baldwin is responding to the fact that Jews are a people who articulate ourselves as having been enslaved.

nf: I’m thinking too about how some of the racialized stereotypes of Jewish people are “positive.” Baldwin writes, “And if one blames the Jew for having become a white American, one may perfectly well, if one is black, be speaking out of nothing more than envy.” I grew up listening to hip-hop, and every other line is like, “I got a Jewish lawyer” or “I’m in Hollywood and my agent is Jewish”; Jewishness is equated with success. There’s a long history of Black people who have admired—however problematically—Jewishness in America. We need to interrogate that.

CPW: I want to name that what you’re talking about is the model minority myth,[5] which can seem like it serves you, but there are sharp edges to it.

BR: I think nyle is suggesting that there might be a particular investment among non-Jewish Black people in a Jewish model minority myth, perhaps partly because of how the Exodus narrative plays such a key role in this dialogue in the way that you’ve described, Chanda: a unique identification with Jewish people in the US due to the shared narrative of enslavement.

Kyrie Irving responding to accusations of antisemitism during a press conference, November 3rd, 2022.

In a twisted way, this seems relevant to contemporary controversies as well—for example Kyrie Irving’s endorsement of the Hebrews to Negroes film. The whole claim that Black people are the true descendants of ancient Israelites, while perhaps symptomatic of a more general Christian supersessionist logic, also relies on the narratives of exile and enslavement that are central to Jewish tradition. The claim wouldn’t make sense without those narratives and the realities they map onto in the US context, realities from which Jews were overwhelmingly spared or in which they were complicit. So I wonder if it is not precisely white Jewish identification with this tradition that then motivates the claim that white Jewish identity is fraudulent. And, once you’re there, it’s easy to activate antisemitic, conspiratorial discourses on Jewish duplicitousness and control.

DM: Absolutely. I want to return to the way that this supersessionist logic is central to centuries of Christian anti-Jewish thought. According to classic supersessionist thought, Christianity fulfills the promise of the Hebrew Bible and renders Jews something between misguided and malicious. I think this is part of why, toward the end of the essay, Baldwin suggests that the central issue is not whiteness but Christianity. In Harlem, as he puts it, the Jews are just doing the “dirty work” to which they have been assigned by “Christians.” He writes, “The most ironical thing about Negro anti-Semitism is that the Negro is really condemning the Jew for having become an American white man—for having become, in effect, a Christian.” And “Christendom” is what has “so successfully victimized both Negroes and Jews.” He is clearly indicting Jews for having become “Christians,” but is he also suggesting that antisemitism, where it exists among Black folks, is a product of them having become “Christian” as well? How are we to understand Baldwin’s turn, in the essay’s final sections, to Christianity?

“Baldwin is clearly indicting Jews for having become ‘Christians,’ but is he also suggesting that antisemitism, where it exists among Black folks, is a product of them having become ‘Christian’ as well?”

MLH: He’s certainly not talking about religious practice; Christianity—unlike Jewishness, which can be seen as a national identity, a religious identity, a cultural identity—is a proxy. It really just means American—and American means white. American means not-the-Negro.

CPW: I actually do think that the religious element is important—religious not necessarily in the faith sense, but in the institutional sense. He’s talking about the colonial architecture that undergirds whiteness in the United States. By naming the role that the white church has played, he’s pointing to a history of antisemitism and anti-Blackness that is deeply tied to the history of European Christianity.

nf: Baldwin is deeply disappointed in the church. He became a preacher at 14 years old, and then, he says, he saw the hypocrisy—and not just of the white Christian world. It’s true that Black people in Harlem can’t be the shopkeeper or the landlord, but they can still do harm—to queer people, to women, to the hustlers on the street.

I also see “the Christian” here as sort of imaginary in a similar way to “the Jew.” I agree with Marc that it’s a stand-in for a particular kind of person that, yes, has everything to do with being “American,” but is perhaps more specifically about being a capitalist, about being an exploiter. But what does it mean to blame the Christian? I’m thinking of a conversation Baldwin had with Audre Lorde, where he makes a memorable distinction between fault and responsibility:

I walked the streets of Harlem . . . Now you know it is not the Black cat’s fault who sees me and tries to mug me. I got to know that. It’s his responsibility but it’s not his fault. That’s a nuance . . . I’m trying to say one’s got to see what drove both of us into those streets.

Here Baldwin reminds me of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel who said: “Some are guilty, but all are responsible.” The point is, we may not have caused the fire but we’d be, in Baldwin’s words, “moral monsters” to just sit there and watch it burn.

BR: Still, it’s interesting to me that the final paragraph of the essay is definitive about assigning responsibility in a

way that the rest of the piece isn’t. He ends with: “The crisis taking place in the world, and in the minds and hearts of black men everywhere, is not produced by the star of David, but by the old, rugged Roman cross on which Christendom’s most celebrated Jew was murdered.”

DM and nf: “And not by Jews”!

DM: A key final sentence.

BR: I think that that gets to this whole mess! You have this Jew, who is murdered on the cross of imperial Rome, yet who is eventually identified with this cross and comes to herald the modern world—slavery, colonialism, etcetera. Baldwin is bringing this all into the picture in a very long historical frame. Perhaps he meanders through the piece, but he is clear on this final point about the source of the crisis.

nf: Baldwin was heavily influenced by the King James Version of the Bible. The “old, rugged Roman cross”—that’s sermonic. He’s using the symbology and language and cadence of the church to critique Christianity. As we say, he left the church, but the church never left him.

Baldwin’s not writing as an academic or a formal historian. He’s writing as a witness, who’s trying not to just lay out a set of facts, but to tell a broader truth about the world—not just to have a conversation about antisemitism, but also a conversation about collective liberation. He’s asking—as he’s always asking—“Where do we go from here?” And who will we become as we journey together?

A movement of Black Hebrews who believe that Ethiopians descend from one of the lost tribes of Israel.

A reference to tensions that played

out around Korean shop owners in

Black neighborhoods in

Los Angeles, particularly during

the Rodney King riots in 1992.

The first law to establish standards and procedures by which immigrants could become US citizens.

Written in response to a “Call for Unity” by white clergymen who argued that the battle against segregation should be fought gradually through the courts and not through civil disobedience, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” expressed frustration with white moderates who effectively asked Black people to “wait” for equality.

The idea that typically non-Black and non-Indigenous minoritized ethnic and racial groups enjoy disproportionate socioeconomic success because of distinct cultural proclivities.

nyle fort is a minister, activist, and scholar of race, religion, and contemporary social movements. He is currently an assistant professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University and a faith-based organizer with the Dream Defenders.

Marc Lamont Hill is the Presidential Professor of Urban Education at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. His scholarly research interests include Israel/Palestine, transnational political solidarity, and anti-racism. He is the author of several books and the host of TheGrio With Marc Lamont Hill and UpFront on Al Jazeera English.

Daniel May is the publisher of Jewish Currents.

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein is an associate professor of physics and core faculty member in women’s and gender studies at the University of New Hampshire. Her scientific work lives at the intersection of particle physics, cosmology, and astrophysics. She is also a theorist of Black feminist science studies, and the author of The Disordered Cosmos.

Ben Ratskoff is assistant professor of Modern Jewish History and Culture at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion’s Skirball Campus in Los Angeles and the University of Southern California.