What Went Wrong With Identity Politics?

In a new book, Asad Haider makes the case for coalition-building and a return to universalist radical movements.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1996, young black boys began convening in a Prince George’s County, Maryland suburb to play basketball. They came to Perrywood, Upper Marlboro’s new community, from Washington, DC and the surrounding areas, seeking a court that didn’t exist near their own homes. Perrywood was overwhelmingly black, leaving the boys to assume they’d be welcomed with open arms—or, at least, tolerated without much fuss. However, Perrywood was also reserved for the upper middle class; its homes sold for $180,000 to $300,000, about $292,000 to $486,000 today, accounting for inflation. As the boys began to frequent the court in throngs, Perrywood’s black residents grew nervous enough to assemble a private police force (consisting of off-duty Prince George’s County officers) to discourage them from returning. While they claimed hesitation to resort to policing, the citizens of Perrywood cited a spike in break-in and vandalism reports as the basis for their fears—despite the homeowners association “not directly connect[ing] the outsiders with security problems,” as neighborhood watch chairman Anthony Jaby said at the time.

It was a culture clash that might seem strange to contemporary eyes. At the moment, using the police to enforce unspoken social boundaries seems like a distinctly white trait, but the Perrywood incident complicates a strictly racial analysis. In the case of Perrywood, the police were used to enforce class rules, proving not only that not all skinfolk are kinfolk, but also that power imbalances are still not restricted along the color line.

This is, in part, what Asad Haider illustrates in his new book, Mistaken Identity (Verso), a meditation on how identity politics have become detached from their radical origins. Part scholarship and part memoir, this slim volume catalogs the history of the anti-racist struggle through the black radical tradition, starting with the Combahee River Collective and moving through the Black Panther Party, Malcolm X, the Black Power Movement, and more, with dashes of contemporary movements added to the mix.

Building on his own experience as a third-culture kid—born in Central Pennsylvania to Pakistani parents—Haider expresses a tenuous relationship with his own identity. For a time, it seemed to shift depending on his surroundings. “ Whatever bits and parts may have constituted my selfhood appeared to be scattered all over the globe. Identity . . . appeared to be externally determined—or perhaps more saliently, not determined.” He saw himself as different—from both his peers and even somewhat from his family—but this difference, and its consequences, wouldn’t come into focus until after 9/11. “Until then, I had learned to live with a culture of condescending and exclusionary toleration. But now it revealed an undercurrent of open hostility.” He still felt no real attachment to his identity, but it rendered him vulnerable nonetheless, as his color was enough to make him stand out as a target.

Haider ultimately comes away from his childhood—the most formative period for identity-creation—“convinced of the impossibility of settling on fixed territory.” Like most first-generation Americans, he found that his identity lacked the steady footing his elders found in Pakistan or white counterparts did in post-9/11 jingoism. In this new cultural landscape ruled by fear, Haider only found vulnerability where others found security—in his identity. So he followed a different path, forged by Huey Newton, resisting the temptation to become a model minority through full assimilation into to the American mainstream. Newton’s radicalism, coupled with Noam Chomsky’s rationalism, “confirmed that I did not have to rely on my identity to argue that the solution to the violence and suffering that assaulted us in our daily news was an end to American imperialism,” Haider writes. What he found over time, however, was that political rigor and sober thoughts couldn’t provide most Americans the consolations they needed to feel secure—that what Americans once found in church, they now found in identity.

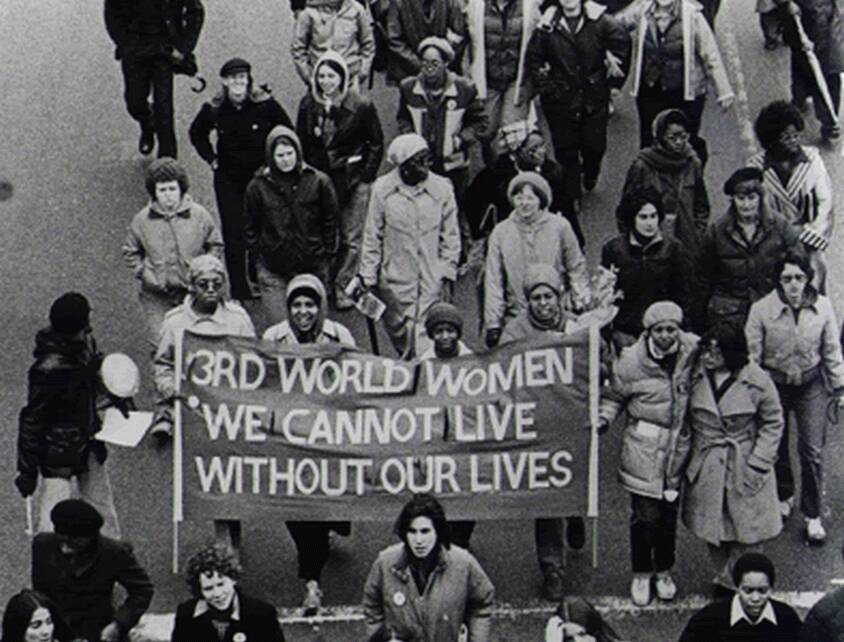

There are valid reasons why Haider chooses to focus on black radical history in making his point. First and foremost, identity politics were introduced and defined by that name by the Combahee River Collective Statement in 1977. The Collective, a black lesbian organization based in Massachusetts, addressed the ignorance of interlocking oppressions in the throes of second-wave feminism: “We believe that sexual politics under patriarchy is as pervasive in Black women’s lives as are the politics of class and race.” While mainstream feminism at the time was focused on helping white women gain equality in the workplace and propagating the sexual revolution, the Collective found their needs as black, queer, working-class women ignored. The Collective’s proposal was to recognize how all of these factors worked in concert with one another, and to then build coalitions with other peoples and organizations to counteract the corresponding oppression; that is, identity politics served as a means for togetherness.

Today, however, identity politics serves to further divide marginalized people within both liberalism and the left. Championing racial and sexual diversity has become a convenient PR strategy for corporations in need of a boost in revenue, while liberals and leftists have too often leaned on lived experience to give their political and cultural critiques potency. As Kimberly N. Foster, founder of the blog for black women For Harriet, recently noted in The Guardian, “When identities can be invoked to assert an unquestionable authority, marginalized people can get by making dubious or completely false claims because of their ‘lived experience.’”

The distortion of identity politics has mainly given rise to small separatist armies, people assembling based strictly on one aspect of their identity—most often the color line. Many black people—not all, but enough—see blackness as the only inhibiting force in their lives, and blackness alone begins to dominate the discourse about black people. As a result, it is assumed that all blacks desire the same thing (inclusion) due to the same experiences (exclusion). But this assumption is at odds with our reality: An Ivy-educated law student trying to get a position at a New York firm has likely not experienced the same oppressions as a working-class mother struggling to keep the lights on in Ferguson. The former may yearn for a seat at the table, still harboring faith in the meritocracy; the latter may seek a break from her situation altogether. What’s similar is not the same.

Haider, Foster, and a cavalcade of other public intellectuals—Kimberlé Crenshaw and Mark Lilla, for example, to very different degrees of success—are attempting to exhume the Combahee River Collective’s original vision. Identity politics have not only been co-opted by those in power, but diluted in the public consciousness over time. The aims of black radicals have been softened so that schools teach that Dr. King sought only racial equality, rather than economic justice for working-class Americans across the rainbow; the Black Panther Party only aimed to feed hungry children, rather than to spur the social, financial, spiritual and literal emancipation of black America. Mistaken Identity serves as a comprehensive overview of how far liberals and the left have strayed from the true aims of identity politics, and what it’ll take to bring them back: abandoning ethnic absolutism and reorienting leftist politics from the particular to the universal through coalition-building.

Kaila Philo is a writer and bookseller living in Baltimore, Maryland.