How “Pro-Israel” Orthodoxy Keeps US Foreign Policymaking White

Recent attacks on Raphael Warnock are part of a long history of Black politicians being targeted for sympathizing with Palestinians.

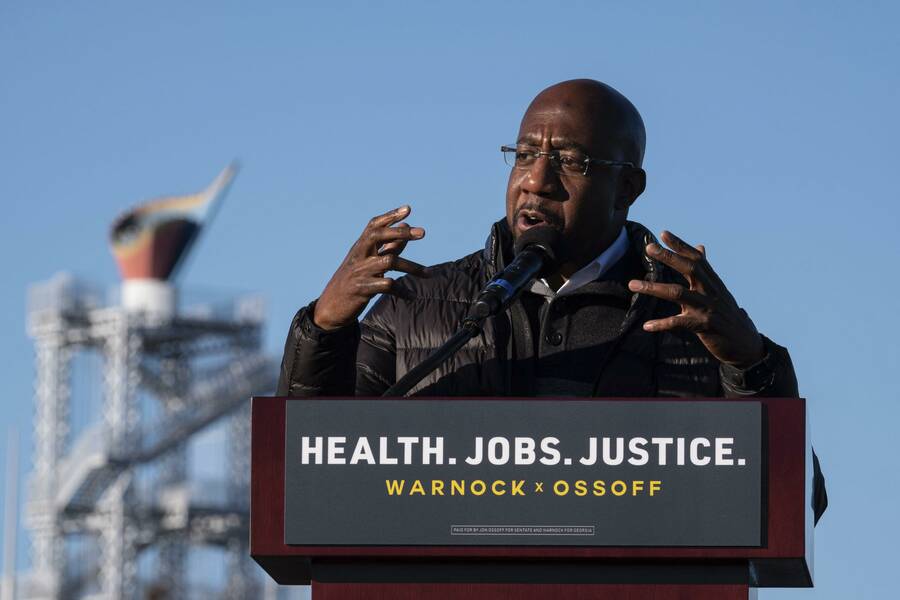

IN OCTOBER, Sen. Kelly Loeffler, who is seeking re-election in Georgia, released an ad called “Birds of Prey” attacking her Democratic opponent, Raphael Warnock. The title refers to a sermon Warnock gave during protests in the Gaza Strip in 2018, in which he accused the Israeli government of shooting “unarmed Palestinian sisters and brothers like birds of prey.” In a statement accompanying the ad, Loeffler called Warnock “the most anti-Israel candidate anywhere in the country.” The next month, she unveiled a new commercial, which again denounced Warnock as “anti-Israel.” When the two candidates debated in December, she accused him of having “called Israel an apartheid state.”

Black politicians often face such accusations. In June, the Republican Jewish Coalition accused Jamaal Bowman, who ousted longtime incumbent Eliot Engel in New York’s 16th Congressional District, of supporting “anti-Israel policies.” In April, the right-wing Jewish newspaper The Algemeiner alleged that California Rep. Barbara Lee had “a clear anti-Israel voting record.” Last year, Republican congressional leaders demanded that Rep. Ilhan Omar be removed from the House Foreign Affairs Committee for her “anti-Israel statements.” In 2018, Florida gubernatorial candidate Ron DeSantis called his Democratic opponent, Andrew Gillum, “anti-Israel.” And in 2017, the American Jewish Congress sent letters to members of the Democratic National Committee warning that if they chose Congressman Keith Ellison as the party’s chair, it “could threaten the relationship between America and our ally Israel.”

Not all Black politicians run afoul of “pro-Israel” orthodoxy. But they do so more frequently than their white counterparts. For nearly half a century, Black politicians who draw on their own experiences to support nationalist and anti-imperialist movements in the developing world have been accused of anti-Americanism. And in a political culture where Israel is seen as embodying the same values as the United States, Black support for the Palestinian cause has often been deemed anti-American too. Year after year, decade after decade, these attacks have forced Black politicians to either mute their sympathy for Palestinians or risk losing a seat at the table. In this way, the Israel debate has helped keep American foreign policymaking disproportionately white.

THE HISTORIAN CHARLES MAIER has argued that the 20th century produced two overarching storylines. Each features an atrocity and a remedy. The first narrative, which Maier calls “Western or Eurocentric,” takes Nazism—or totalitarianism more generally—as its core moral offense. In this narrative, the West committed a ghastly crime against itself, but then overcame its own evil when the US helped to defeat first Nazi Germany, and then the Soviet Union, thus saving European democracy. Israel’s creation, as Bashir Bashir and Amos Goldberg have noted, fits into this redemptive story. By creating a Jewish state, the West provided a home to the victims of its greatest horror.

This narrative pervades American foreign policy discourse. Antony Blinken, Joe Biden’s nominee for secretary of state, articulated it last month when he told the story of his stepfather, Samuel Pisar, who escaped from a Nazi death march after four years of living in concentration camps. Upon seeing an American tank, Pisar fell to his knees and uttered the only English words he knew: “God bless America.” “That’s who we are,” Blinken declared. “That’s what America represents to the world.”

Blinken didn’t mention Israel, but he didn’t have to. In the Western narrative, America’s rise to global power and Israel’s creation are considered two of the 20th century’s great redemptive acts. In this pairing, attacks on Israel’s virtue become attacks on America’s. Indeed, Loeffler links support for the Jewish state and loyalty to the United States in her critique of Warnock: The section of her website devoted to his “anti-Israel” statements falls under the heading “Anti-American values.”

Yet there is, Maier writes, a second great 20th-century narrative, which emphasizes a different moral atrocity: Western imperialism. In this anti-imperialist narrative, the US doesn’t overcome Europe’s sins; it perpetuates them. It replaces European colonialism with US neo-colonialism. And Israel represents not the antidote to Nazism, but a continuation of the imperialist project. In this narrative, which emphasizes “the domination of the West over the massive societies of what once could be called the Third World,” redemption comes not from American power but from the African, Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latin American nationalist movements that challenge it. Many of those movements challenge Israel, too.

Since the US rose to global power in the mid-20th century, influential Black intellectuals and activists—motivated by their subjugation at home and their identification with people of color around the world—have challenged the Western narrative and embraced the anti-imperialist one, thus contesting the dominant American political discourse. As the historian Gerald Horne has observed, “it may inhere in the nature of being an oppressed nationality to adopt viewpoints that are considered to be beyond the mainstream.” In the 1940s and 1950s, the singer and activist Paul Robeson and the sociologist W.E.B Du Bois, who had helped found the NAACP, sympathized with the Soviet Union because they saw it as a force not for totalitarianism but for anti-imperialism. In the 1960s, according to activist Karen Edmonds, in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), “[e]veryone in their hip pocket carried [Frantz] Fanon,” the Martinique-born theorist of anti-colonial liberation.

Some Black leaders, like Martin Luther King Jr., embraced these anti-colonial struggles without challenging Israel’s legitimacy. In 1957, King declared that “[t]he determination of Negro Americans to win freedom from all forms of oppression springs from the same deep longing that motivates . . . people who have long been the victims of colonialism.” Yet he also defended Zionism. Malcolm X, by contrast, asserted in 1964, “The Israeli Zionists are convinced they have successfully camouflaged their new kind of colonialism.”

By the 1970s, the civil rights movement had made it possible, for the first time since Reconstruction, for Black Americans to enter elected and appointed office in significant numbers. But as they entered the halls of power, Black politicians and government officials learned how intolerant both parties were of the anti-imperialist narrative. And frequently, the point of friction was Israel.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed Andrew Young, a former aide to King and the first Black congressman from Georgia since the 19th century, as the first Black US ambassador to the United Nations. He was soon attacked for his ideological transgressions. In 1978, while discussing Soviet dissidents, Young said that the US itself had “hundreds of people that I would categorize as political prisoners in our prisons.” For drawing a comparison between the Soviet Union and the US, and thus muddying the moral Manichaeism that characterized the Western narrative, Young found himself the subject of an impeachment effort in the House of Representatives. That effort failed. But the following year, Young faced even greater criticism for an act considered even more incendiary: In violation of US policy, which deemed the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) a terrorist organization, Young met one of its representatives in New York. After an outcry from the Israeli government and its supporters in the US, he was fired.

Not all Black activists defended Young. Bayard Rustin, a veteran civil rights organizer and staunch defender of Israel, argued that given the PLO’s use of violence, Black “identification and even solidarity with the P.L.O. is based on a terrible perversion” of the civil rights movement’s commitment to nonviolence. But many other Black leaders saw Young’s dismissal as a threat to the ability of Black Americans to draw on their own experience and worldview in shaping US policy overseas. “There has long been sympathy for Arabs among the masses of Blacks,” noted former SNCC co-founder Julian Bond. In a clear dig at Israel and its US allies, the NAACP declared, “We summarily reject the implication that anyone other than Blacks themselves can determine their role in helping to shape and mold American foreign policies which directly affect their lives.”

In another act of defiance, Joseph Lowery, King’s successor as head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), announced in 1979 that he would lead a delegation of Black Ministers to Beirut, where they would meet PLO leader Yasser Arafat and try to convince him to recognize Israel and institute a moratorium on violence. Rejecting Rustin’s admonition not to connect the Palestinian struggle to the struggle for civil rights, the ministers locked arms with Arafat and sang “We Shall Overcome.” In his book Black Power and Palestine, historian Michael R. Fischbach notes that Lowery advised Arafat to organize a march of Palestinian refugees from Southern Lebanon to the Israeli border.

As a minister and activist, Lowery could more easily ignore criticism of the trip. But another member of the delegation, Walter Fauntroy, who served as Washington, DC’s delegate to Congress, was more vulnerable politically. After lugging home shrapnel from US-made artillery that Israel had fired into Lebanon, Fauntroy called on Congress to slash military aid to Israel by 10%. With other leaders of the SCLC, he also invited Arafat on a speaking tour of the US.

Like Andrew Young, Fauntroy quickly realized how difficult it was to hold political office and advocate an anti-imperialist politics at the same time. Rabbi Joshua Haberman of the Washington Hebrew Congregation told The Washington Post, “I expect Mr. Fauntroy to act always in the interest of America and not just be a black leader”—as if Black leaders could not draw on their own experience to determine what best served the US. A few weeks later, after the Post reported that “Fauntroy’s contacts with the PLO [had] sparked criticism in the local Jewish community, which includes many persons who had played key roles in raising money for Fauntroy’s political campaigns,” Fauntroy rescinded his invitation to Arafat.

Although less noticed at the time, another Black minister with political ambitions, Jesse Jackson, was organizing his own trip to meet Arafat in Beirut. In 1979, before leaving for the Middle East, Jackson gave a speech to the Palestine Human Rights Campaign in which he cited the persecution of Du Bois and Robeson as evidence that “[t]here is and has been for a long time a concerted effort to . . . challenge the audacity of black involvement in foreign affairs.” When Jackson visited the West Bank’s Qalandiya refugee camp, he explicitly linked the Black and Palestinian experiences. “I know this camp,” Jackson said. “When I smell the stench of open sewers, this is nothing new to me. This is where I grew up.”

Jackson continued to express sympathy for left-wing movements in the developing world even as he prepared for his 1984 presidential run. He visited Cuban leader Fidel Castro and praised the Sandinista government in Nicaragua, which the Reagan administration was trying to overthrow. But he also badly undermined his credibility as a critic of Israel by allowing Louis Farrakhan to introduce him at some early campaign rallies, and, infamously, calling New York City “Hymietown.” Jackson apologized twice, first at a New Hampshire synagogue and later at the Democratic National Convention itself. Yet in a revealing response, Nathan Perlmutter, the Anti-Defamation League’s national director, told The New York Times that Jackson’s greatest offense was not his “anti-Semitic vulgarities,” but what the Times called his “gestures of accommodation toward leftist governments such as those of Cuba and Nicaragua and such Arab leaders as President Hafez al-Assad of Syria and Yasir Arafat.” In Perlmutter’s view, Jackson’s most significant transgression was flirting with anti-imperialist politics.

WHEN BARACK OBAMA ran for president more than two decades later, many conservatives assumed that he too harbored dangerous sympathies for anti-imperialist movements in the developing world. The key to understanding Obama, Newt Gingrich suggested, was “Kenyan, anti-colonial behavior.” Rudy Giuliani described Obama’s worldview as “socialism or possibly anti-colonialism.” Ben Shapiro posited that “Obama Despises Israel Because He Despises the West.” In fact, Obama’s foreign policy, including toward Israel, did not deviate substantially from that of his white predecessors. Still, as his aide Ben Rhodes noted, “Just the presumption that because Obama was Black he would be sympathetic to Palestinians was enough to cause political problems with certain donors and elements in the media who assumed that would mean that he was anti-Israel.”

Meanwhile, in Congress, Black politicians continued to risk their careers by visiting the West Bank and expressing identification with the Palestinian cause. After Maryland Representative Donna Edwards visited Hebron on a J Street-sponsored trip in 2012, she remarked that “it looked like the stories that my mother and my grandmother told me about living in the [segregated] South.” After being stopped by Israeli soldiers on their way to meet nonviolent Palestinian activist Issa Amro, Edwards and the five other Black congresswomen on the trip joined arms and began singing “We Shall Overcome,” just as the SCLC ministers had with Arafat more than three decades earlier. When Edwards sought a senate seat in 2016, The Baltimore Sun warned that she had “repeatedly opposed broadly bipartisan resolutions supporting Israel.” Pro-Israel donor Haim Saban donated $100,000 to her Democratic opponent in the waning days of her Senate primary campaign, and Edwards lost. That same year, Georgia Congressman Hank Johnson made his own visit to the West Bank. After returning, when he compared Israeli settlements to “termites” eating away at Palestinian land, the Georgia Republican Party demanded that he resign, and Johnson apologized.

The attacks on Warnock fit squarely within this half-century-long tradition of Black politicians being excoriated for challenging establishment discourse on foreign policy. Republicans are not only condemning Warnock’s views on Israel. They cite his statements on Israel as evidence of his transgression against the Western narrative, which sees both the US and the Jewish state as beyond reproach. Echoing the critics who called Andrew Young anti-American for claiming the US held political prisoners, the Loeffler ad that calls Warnock “anti-Israel” also describes him as “a proud defender of anti-American, anti-Semitic pastor Jeremiah Wright.” It then quotes Wright, in a sermon on racism and inequality, declaring, “Not God bless America, God damn America.” In an echo of the criticism of Jesse Jackson after he visited Cuba, another ad charges that Warnock “hosted a rally for communist dictator Fidel Castro.”

When it comes to Israel, Warnock is under attack for the same basic transgression committed by Jackson, Lowery, and Donna Edwards: Seeing parallels between the Black and Palestinian experiences. In 2016, Warnock analogized Benjamin Netanyahu to Alabama’s segregationist Governor George Wallace. Netanyahu, Warnock declared, was “saying occupation today, occupation tomorrow, occupation forever.” In 2018, Warnock compared Palestinian protests in Gaza to Black protests in the US. “We know what it’s like,” he said, “to stand up and have a peaceful demonstration and have the media focus on a few violent uprisings.” Warnock went on to insist that “it’s no more anti-Semitic” to criticize Israel “than it is anti-white for me to say than that Black Lives Matter.” In 2019, he traveled to Israel/Palestine with a delegation of Black American and South African ministers, who collectively declared, “Based on our own histories and struggles as South Africans and African Americans, we are keenly aware of the need to preserve the option of utilizing economic pressure as a means of bringing recalcitrant dominant forces to the negotiating table.”

In response to Republican criticism, Warnock has revised his positions on Israel, which are now virtually indistinguishable from mainstream orthodoxy. He says he opposes placing conditions on US military aid and claims that the movement to boycott Israel has “anti-Semitic underpinnings.” He has altered his views about the protests in Gaza because of his “increasing recognition of Hamas and the danger that they pose to the Israeli people.” His outlook is now so conventional that he’s won the endorsement of the Democratic Majority for Israel, a group established to ensure that Democrats disavow the very “economic pressure” on Israel that Warnock once endorsed.

If Warnock wins, he will become the first Southern Black Democratic Senator in US history. His views on foreign policy in general, and Israel in particular, will be carefully scrutinized for any evidence that he retains a residual attachment to the Black anti-imperialist tradition. His election would be a sign both of how much American politics has changed in the last half-century—and how little.

Peter Beinart is the editor-at-large of Jewish Currents.