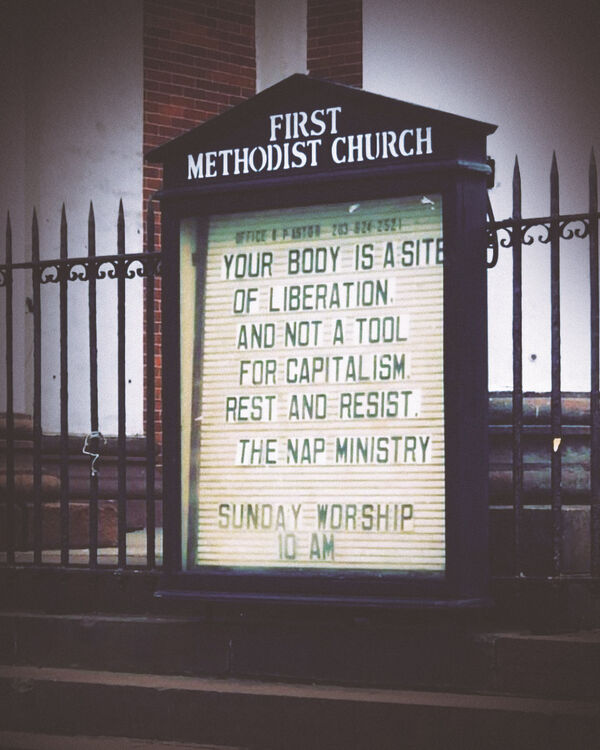

The Nap Ministry’s site-specific installation A Resting Place for Flux Projects at the Ponce City Market in Atlanta, 2019.

Entering the DreamSpace

The new manifesto from the Nap Ministry’s Tricia Hersey argues for a vision of rest as politically generative. But what kind of resistance, really, is rest?

Discussed in this essay: Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto, by Tricia Hersey. Little, Brown, 2022. 224 pages.

Tricia Hersey was a graduate student in theology, putting herself through punishing 15-hour days, when she began reading John W. Blassingame’s Slave Testimony, a 750-page collection of archival history, for a course in cultural trauma. Shaken by the violence of the stories it held, she decided to move through the volume slowly, often falling asleep with it open on her chest. Over the course of six months in 2013, her ancestors and their experiences drew near: Grown men who “cried for hunger” after 20-hour workdays. Lunches of an ear of corn, eaten standing up, without pause. Mothers laboring while in labor, their babies born in the field. A man with a head injury, forced to continue working until he was dead.

Hersey remembered a boss who’d asked her to “just muster up the energy” to come in after a car accident that left her with a pinched nerve. She thought of her father, who’d woken at 4:00 am daily so he could have a couple hours to read and pray before heading out to work two full-time jobs, one as a railroad yardmaster and the other as an assistant pastor in the Black Pentecostal tradition. He was “on the clock twenty-four hours a day,” she writes, and died at 55, when “his body simply gave out.” She thought of her grandmother Ora, a refugee of Jim Crow terrorism who was committed to sitting on the couch with her eyes closed for 30 minutes daily, explaining to a mystified young Hersey, “I am resting my eyes and listening for what God wants to tell me.” With an unrelenting schedule that began at 5:30 am and ended at midnight, Hersey recognized that she “was repeating the violence that capitalism inflicted upon my Ancestors during slavery.” She resolved to experiment with rest herself.

At first, these experiments took the form of 15-minute catnaps and skygazing sessions on benches around campus. Soon, though, Hersey was challenging herself to sleep as much as she could. If capitalism was “from the plantation,” as she often puts it, then Hersey would rest for her ancestors, “for all the centuries they couldn’t.” In an early post on the website for the Nap Ministry—the project for which she’s become known—she explains: “I was desperate to provide a form of reparations for them.”

If capitalism was “from the plantation,” then Hersey resolved to rest for her ancestors, “for all the centuries they couldn’t.”

Before she started seminary and before she became the Nap Bishop, Hersey had been Lady Terror, a “spectacle trickster artist” who hosted yoga classes inside a Harold’s Chicken and shouted poetry through a bullhorn outside 24-hour liquor stores on Chicago’s South Side, where she grew up, on the same sidewalks where her father had once hosted Bible study. In May of 2017, when her graduate program was ending, Hersey performed Transfiguration, a one-night solo show, in Atlanta, where she has lived since 2010. She rested among bolls of cotton before an audience and read aloud from slave narratives, then gathered 40 people to “nap at the rest altar.” On offer were blankets she’d brought from home, soothing music, and an invocation that began, “The doors of the Nap Temple are open.” After two hours, people woke up “crying from the realization of how exhausted” they were.

That spring, Hersey “stepped full force” into her role as the leader of what she calls a rest movement. With a youth collective in Chicago, she installed a series of Nap Revivals in city parks, complete with a white tent painted “COME NAP” and hand-lettered signs inviting passersby to “Come And Expect a Supernatural Healing Via Rest.” Another public napping ritual, Reparations LIVE!, used “sleep as resistance . . . to recapture the DREAM SPACE that was stolen centuries ago.” Hersey has since hosted Collective Napping Experiences online and in person for thousands of people, incorporating mats, pillows, music, and her own invocations to “open the portal of rest.” Her Nap Ministry has borne a series of photographs of herself and friends resting in sumptuous outdoor landscapes (exhibited at the Atlanta airport in 2021), an event series called the Resurrect Rest School (assigned reading: bell hooks, Martin Luther King, Jr., Audre Lorde), a hotline featuring rotating recordings of Hersey reading poems and meditations (1-833-LUV-NAPS), an addictive R&B-inspired single (“Rest Life”), a Rest Temple (opened in 2022 in a Presbyterian church), a viral Instagram account (@TheNapMinistry), and, finally, a book, Rest Is Resistance, which debuted as a bestseller this fall.

The message of the Nap Ministry, as related in Rest Is Resistance, is simple, maybe bafflingly so: Rest. Ten or 20 minutes, even just one minute, will do; sitting in your car in the grocery store parking lot is fine. This isn’t the cheap “rest” I might think I’m giving myself when I shut my computer and collapse on my back with Instagram, Duolingo, and a dating app, nor is it the “rest day” of fitness gurus, which is supposed to improve our strength and speed tomorrow. Hersey is not advocating rest so we can do our work better. The rest she preaches is somatic, spiritual, generative; it encourages imagination and honors daydreams and REM dreams both. “There is information in your body that wants to be heard,” she counsels, “but it can only arrive to you in a rested state.” Where the grind culture produced by capitalism and white supremacy asks us to be “hard and machine-like,” Hersey’s rest “keeps us tender.” She often calls it a “meticulous love practice.” Through rest, she argues, our bodies can become “a site of liberation.”

From a distance—on social media, that is—it can seem that rest is resistance the way that art is resistance, the way that prayer is resistance, the way that sex without procreation is resistance. It makes us feel good to call something resistance, the way it feels speciously good to click the ads in the feedlots of our digital lives and order metal straws or recycled rain boots to be shipped to our doorsteps from China. When I started talking with friends about Hersey’s new book, I found that many were reluctant to wholly embrace its proposition, which threatened to moralize what had once been a slothful and indulgent pleasure into a too-tall glass of milk. “Why can’t rest just be rest?” one person complained. Could anything be resistance other than resistance itself? What kind of resistance, really, is rest?

The message of the Nap Ministry, as related in Rest Is Resistance, is simple, maybe bafflingly so: Rest.

Like about 200,000 other people, I first encountered the Nap Ministry online in the early months of the Covid pandemic, when some of us were confronted with endless rest, and others with the terror of having even less time for rest than before. During the uprisings in the wake of Breonna Taylor’s and George Floyd’s murders, Hersey’s efforts to shift consciousness by sharing images of Black bodies “in a safe and rested position . . . in a beautiful, sacred space,” as she put it to Black Lives Matter founder Patrisse Cullors, landed with all the more force. As the pandemic continued, Hersey seemed to capture a wider collective longing: In China, a lying-flat movement gathered momentum, while Portugal passed a “Right to Rest” law, preventing employers from contacting their employees outside of working hours. Meanwhile, Hersey’s practice as the Nap Bishop became a career.

If you approach Hersey’s project through the lens of influencer culture alone, it would be easy to shrink from what can read as a creeping proprietariness in the Nap Ministry’s most visible work. Though she takes pains to portray the quiet subversion she advocates as “an ancient practice,” Hersey also emphasizes in her book and in public appearances that she is “the creator of the Rest Is Resistance and Rest as Reparations frameworks”; the phrases are always capitalized, as are others like “Collective Napping Experience.” Such choices might well be justified by the fact that, as a Black woman, Hersey is part of the community whose collective labor has been more stolen and less credited than anyone else’s in this country. At the same time, they can lend her anticapitalist message an unsettlingly capitalistic aesthetic. Hersey preaches often, for example, of “DreamSpace,” that “sacred place” for healing, imagination, and communication with ancestors that is accessed via rest, where we “can work things out,” daydream, slow down, and reinvent. DreamSpace is a beautiful concept, maybe the most important aspect of the Nap Ministry project, but the word as it’s styled in print can conjure one of those calm-energy drinks a friend in LA is always trying to get me to buy. In other words, it looks like a brand.

Rest Is Resistance is subtitled “A Manifesto,” and is woven through with italicized poetic meditations. It includes bulleted “techniques to create space to dream,” a “not-to-do list,” and a list titled “How to Rest.” Equal parts how-to and memoir, it’s a book informed by scholarship that’s nevertheless unconcerned with conventional scholarly markers: “Rest saved my life,” it begins; “I don’t need anyone else to verify this, nor do I need complicated theories to support what I know to be true.” Many of its readers will be familiar with Lorde, hooks, King, and the other figures it cites as “paper mentors”; the bibliography lists just 11 titles, and is topped with a note encouraging us to consider spending years with just one. Though I was ultimately convinced by the book’s message, when I first started reading, I floundered in the repetitiousness of its pages. Later, I’d see Hersey explain that the book uses repetition as “a deprogramming tool . . . in the spirit of Black Church sermons”; after I heard her read aloud from the pages of Rest Is Resistance, I understood that the book is a printed-out sermon, and Hersey, who speaks with the resonant voice of a reverend, its preacher. While both a book and a social media account are convenient tools for reaching a crowd, neither is the Nap Ministry’s ideal medium. On paper or in pixels, the cry, “We will rest! We will rest!” can seem flimsy; in person, it resounds.

A Nap Ministry event at a New Haven, Connecticut, church.

Rest Is Resistance is a printed-out sermon, and Hersey, who speaks with the resonant voice of a reverend, is its preacher.

As uncomplicated as its message is, the Nap Ministry seems to provoke a notably complicated reaction. For those of us who define ourselves and our value through our labor, the injunction to rest can threaten our very identities. Hersey has received lengthy emails from people explaining why they don’t have time to rest—when, she notes, they could have rested instead of writing to her in panicked anguish. Born of what Hersey calls “internalized capitalism,” this terror may be the most significant, and least obvious, source of hesitation with which a reader might approach her work. Once we are “deep into the cycle of brainwashing,” she argues, “we don’t want to rest, we don’t know how to rest, and we don’t make space for others to rest”: We become agents of grind culture ourselves.

Hersey’s interest in rest as reparations and the Nap Ministry’s grounding in the history of plantation slavery could suggest to an audience unaccustomed to centering Black bodies or Black history that her project is meant only for a Black community. But Hersey is adamant that the Nap Ministry “is for all those suffering from the ways of white supremacy and capitalism”—that is, for “everyone on the planet, including the planet itself.” Her first-ever public presentation of the Nap Ministry was for an audience of Google employees in Chicago who were overwhelmingly white men. She was surprised when, after her five-minute offering, they stood to applaud. In the 2018 conversation where she recalls that experience, she explains that rates of sleep deprivation in the US are higher than anywhere else in the world. This is “a public health issue and a spiritual issue,” she writes—exhaustion causes diabetes and heart disease and erodes our mental health, while sleep is a means of biological and neurological repair. Still, sleep is also “a racial and social justice issue”: It’s well established that, in the US, Black adults and other people of color tend to be more sleep-deprived than whites.

This might be why, while it gets less airtime than her case for rest as resistance, Hersey’s argument for rest as reparations is easier for some people to swallow: Reparations are less abstract than “resistance,” for one thing, and US history makes the case for Black rest in the present painfully clear. One white organizer explained to me that she works as hard and for as many hours as she does in a kind of repentance for her family’s class privilege—an effort that might make Black allies’ rest-as-reparations more possible. Hersey, however, would likely point out that the fact that grind culture grew out of plantation slavery doesn’t mean white Americans aren’t also suffering from its violence. Paraphrasing King, she often reminds her audiences that white supremacy leaves its perpetrators “spiritually deficient,” “blinded by the idea that they are superior to other divine human beings.” When organizers ask Hersey how they’re supposed to rest while the world is burning, she laments the seep of grind culture into activist culture, and quotes Lorde: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Because it encourages us to be machine-like, disconnected from our bodies, and inhumane (including to ourselves), white Americans’ attachment to our own relentless labor might even be another way of quietly endorsing white supremacy.

To “deprogram,” as Hersey often puts it, we need imagination: first, the imagination to find or create space for our own rest—the kind that reconnects rather than disconnects—and then the imagination to dream up other worlds. Hersey describes naps as “a portal” to a wished-for future that is present, a “new memory” inspired by time-bending works of Afrofuturism. In a conversation at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center, she argued that the more we rest, the more inventive our ideas for revolution will become; that sleep must be not a casualty of movement-building but a tool for liberation; that had her ancestors not been systematically deprived of rest they would have been even more ingenious and inventive, and might even have ended their own enslavement sooner. Such is the power of the DreamSpaces we might reclaim. “The world will be led by rested people,” she said.

“The world will be led by rested people.”

I read Rest Is Resistance on what Hersey would call a digital Sabbath, in a cabin in the New Hampshire woods without phone service, internet, electricity, or running water, which a person I’ve never met has been letting me stay in as an occasional artist residency for the past couple of years. I was there to continue writing a book that might have begun as part of a so-called career, but which in the 15 years I’ve worked on it has become more of a spiritual project. I was reading Hersey’s book for work, sort of—I’m still not sure how to categorize a mildly compensated pleasure like this review—but also because I sensed it might have something to offer me, there in that cabin where for six days I was escaping the responsibilities that pay my bills in favor of a responsibility to my ancestors and myself. A few weeks earlier, I’d found myself sobbing to the person who serves as my de facto therapist that I was tired of trying to stop trying. Earlier that year, I’d admitted to her that I didn’t really know how to rest: What was I supposed to do? To put a finer point on it, I don’t have a bed. In the apartment I can currently afford, I’d rather have creative workspace, which is what I have instead.

Hersey’s particular politics of refusal left me wondering about my own inherited practices of rest, the ones from which whiteness has alienated me. Her offering is in conversation with those of other justice-based Black healer-activists like Bayo Akomolafe, adrienne maree brown, and Resmaa Menakem, whose work I’ve turned toward in an attempt to unlearn white supremacy and build a politics of care that also includes care for myself. In that sense, it felt effective. I opened the book when I was tired, or when mice and chipmunks startled me awake in the middle of the night, and it exerted a spell. I’ve probably taken as many naps in the two months since reading it as I have in the past ten years—prior to reading Rest Is Resistance, I was a never-napper. Now, each time I feel a midday wave of exhaustion and decide to lie down, the act has something of an exalted, holy feeling.

If a weekday nap feels the tiniest bit subversive, though, it has yet to feel to me like “resistance,” at least not in the sense that might correspond to direct action. While I was in New Hampshire, I missed my part-time faculty union’s first major rally for fair pay; parts of this review were since written “in” online bargaining sessions with the volume turned down so that I could just barely hear my union reps putting in consecutive unpaid 12-hour days to advocate for our working conditions. Revising this in the thick of a strike, I’m torn between hope at the possibilities of a more direct confrontation with late-capitalist greed, and dismay at the confrontation’s physical and material costs. The gulf between the system of higher education I might envision in my DreamSpace and the pittances we’re fighting for feels sickeningly large.

At the same time, to fault Hersey’s project for failing to advocate for more practical collective action would be to buy into grind culture’s assumption that if you can’t see what’s happening, then nothing is happening at all. Hersey was at a meeting of Black organizers in 2014 when she first encountered the story of those African-descended people in the Americas who, beginning in the 17th century, refused enslavement through marronage: jumping ship, fleeing plantations to settle in the wilderness, and secreting themselves away, sometimes right under a former abuser’s nose. Despite her own upbringing in a church she describes as “a beacon of Black resistance,” she’d never known there were maroons in the US. The discovery led her to the one book she calls “required reading” for the Nap Ministry project, Sylviane Diouf’s Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons. The maroons weren’t runaways to the so-called freedom of urban life or a free state, and they weren’t activists for the abolition of slavery, either. Instead, they “created a whole world within an oppressive one to test out their freedom and regain autonomy,” in Hersey’s words, and lived “in a Third Space, a temporary place of joy and freedom.”

Rest, too, can be a Third Space, and a threat to the dominant culture, as Ross Gay puts it in “Loitering,” an essay that observes “how threatening to the order our bodies are in nonproductive, nonconsumptive delight”—particularly “if your body is supposed to be one of the consumables, if it has been, if it is, one of the consumables around which so many ideas of production and consumption have been structured in this country.” When “the deepest part of oppression lies in the theft of our imagination,” as Hersey and others have argued, then the kind of rest Hersey proposes may well be a radical act.

Helen Betya Rubinstein is a contributing writer for Jewish Currents. Her book Feels Like Trouble: Transgressive Takes on Writing, Teaching, and Publishing is forthcoming. She teaches at The New School and works one-on-one with other writers as a coach.