Changing the Climate

Naomi Klein’s new collection provides a historical overview of the last decade—one that charts how far the environmental left has come.

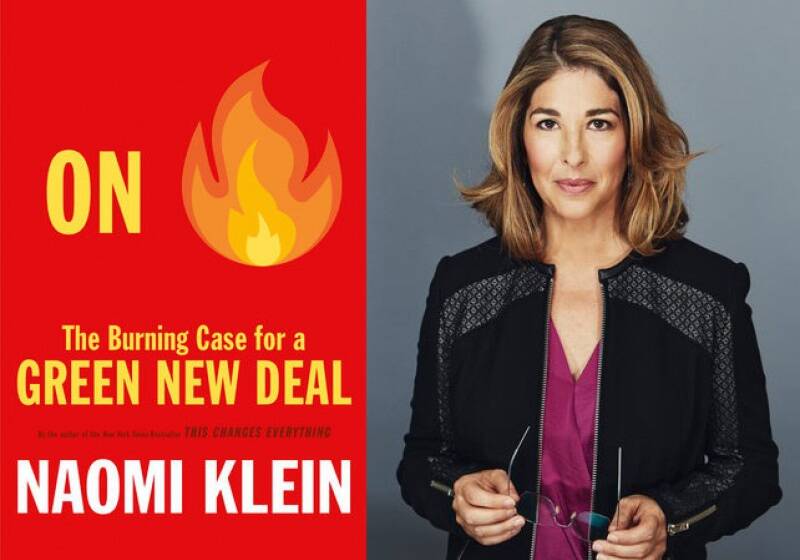

Discussed in this essay: On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal, by Naomi Klein. Simon & Schuster, 2019. 320 pages.

In her 2014 environmental opus, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate, Naomi Klein called for a reframing of the climate movement. Capitalism itself, she argued, was the cause of the crisis, and in order to propose viable, effective responses to global heating, the left would have to see climate change as an opportunity to advance its own causes more broadly. Yet at the time, progressives were dealing with issues—including climate change—piecemeal. Labor wasn’t listening to the greens; the greens weren’t listening to labor. The racial justice movement was largely disconnected from the environmental movement. Indigenous groups were receiving little support from environmental advocates.

Klein had already begun to articulate her position in a 2011 essay, first published in The Nation, in which she wrote that the politically viable way forward would require making a persuasive case that the real solutions to the climate crisis are also our best hope of building a much more enlightened economic system—one that closes deep inequalities, strengthens and transforms the public sphere, generates plentiful, dignified work and radically reins in corporate power.

Klein’s call has been heeded: in the years since she outlined her anti-capitalist climate vision, the environmental left has been born. Movements have coalesced—starting with the Flood Wall Street protests in 2014 and culminating in the Sunrise Movement, the youth-led activist group that’s been instrumental in advocating for climate justice—that recognize capitalism as the prime culprit of the climate crisis. In February, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Ed Markey introduced their Green New Deal resolution. Building on ideas laid out in Klein’s work, it combines economic and green initiatives—calling for the integration of a jobs program; universal, high-quality health care; and public spending on infrastructure upgrades geared toward protecting those poor communities of color that are placed most at risk by climate change—all marshalled as part of a full-scale plan to retool the economy such that fossil fuel–driven growth won’t scorch our planet. In the halls of Congress and on the 2020 Democratic campaign trail, there’s now an awareness that addressing climate change means building a new welfare state, one that can care for the poorest who will be most affected as tides rise and storms become stronger.

With the idea of a Green New Deal now on the table, Klein’s new collection, On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal, compiles her last decade’s worth of essays and speeches on climate and the environment in support of such a plan. But despite its subtitle, the new collection ends up being less a coherent argument for or against any particular slate of green policies, and more of a historical overview of the last decade, one that charts how far the environmental left has come.

And that’s staggeringly far; ideas that once had to be pushed from the fringes of the left have been increasingly accepted as mainstream. In the first essay in the collection—published in June 2010 and concerning the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico—Klein spends a significant amount of time convincing her reader that BP, as an oil company, shouldn’t be trusted. That’s not exactly a hot take in 2019: a June poll from Yale found that the majority of Americans think big oil should pay up for the damage they’ve caused to the climate.

Klein herself deserves credit for helping to bring about this shift. She was visionary, for instance, in her reading of the right’s opposition to taking any action on climate change. In This Changes Everything, she pointed out that conservative opposition to climate science has less to do with contesting the science itself than with opposing its implications, which require solutions that upend the market fundamentalist order they hold dear. The right understood this long before the left, and Klein was among the first to note the opportunity that climate change opens up for a social democratic movement. Decarbonizing can become an occasion to rebuild the public sector and the public square, to push for communitarian values, and to fight for equity.

But even as the broader left has caught up to Klein, reaching consensus on the basic outlines of a Green New Deal, the “how” remains fuzzy. As it stands, the Green New Deal resolution itself is only 14 pages long; it’s a statement of principles, not policy. In On Fire, Klein gestures toward the complications of implementing as drastic an overhaul of the economy as these principles demand. She emphasizes that markets will continue to play a role in the transition, but that they won’t be the be-all and end-all. She argues, in the book’s introduction, that we don’t simply need a New Deal painted green, or a Marshall Plan with solar panels. We need changes of a different quality and character . . . We need to devolve power and resources to Indigenous communities, smallholder farmers, ranchers, and sustainable fishing folk so they can lead a process of planting billions of trees, rehabilitating wetlands, and renewing soil—rather than handing over control of conservation to the military and federal agencies, as was overwhelmingly the case in the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps.

The Green New Deal, in other words, should be a bottom-up endeavor. Federal agencies, she writes, should not lead the decarbonization of the economy. The process should be small-d democratic, and power should be handed over to local economies, decentralizing the energy and fossil-fuel infrastructure that’s put us where we are. But Klein, in this collection, still leaves us short on the details of exactly what shape this will take: How can federal agencies empower communities to retool their energy infrastructure? In a drastic overhaul of the economy, what role does the military play? How do we forge international coalitions to ensure decarbonization takes place on a global scale? These are central, burning questions in the formulation of a Green New Deal, to which Klein proposes no robust answer.

Instead, Klein frequently gets bogged down in the culture wars around the climate crisis. Even as she repeatedly acknowledges the deeply material roots of this crisis, her writing is preoccupied by a nearly spiritualistic anti-consumerism, geared toward convincing her reader that a cultural shift will help solve climate change. She wonders, in “Movements Will Make, or Break, the Green New Deal,” from February of this year, whether “we are ready to have a more probing conversation about the limits of lifestyles that treat shopping as the main way to form identity, community, and culture,” as though consumerism is the main obstacle to climate action, rather than the exigencies of an economic order predicated on perpetual growth.

Of course, in order for any movement to be democratic, a cultural shift is necessary. And Klein is right that, in order to address the climate crisis, consumer culture will need to shift: we’ll have to fly less and buy less, which, Klein correctly notes, may well open us up to “new pleasures and new spaces where we can build abundance.” But what the environmental left may need now is less a shift away from an “extractive mind-set” than the hard policy details. It’s a sign of the left’s ascendance that the author of No Logo, the 1999 book about branding and globalization, has become something of a media brand herself. There’s enough demand for her writing that publishers seem to be clamoring for more of it. Perhaps as a result, On Fire reads like a slapdash and uneven collection. That a publisher sees this stuff as worth repackaging is a good sign for Klein’s cause, but there’s really no reason to read her 2015 commencement speech to the College of the Atlantic’s graduating class.

But despite the padding, there’s much here that’s worthwhile. The most compelling essay in On Fire is, aptly enough, the essay about fire, “Season of Smoke,” originally published in September of 2017. Klein takes a vacation with her family to British Columbia, an attempt at a break from her work as a climate activist, only to find herself under a gray sky, hazed over from the smoke of Canada’s 2017 wildfires. The goal was not to think about global heating for a couple weeks, and to spend time with her five-year-old kid—instead Klein finds herself under a pale sun, surrounded by smoke. She has to explain to her son where the animals go when the forest is on fire; she doesn’t speak to him about climate change, but the subject becomes difficult to avoid. Klein is acutely aware that the fires are burning through woods that would otherwise act as a carbon sink, keeping the greenhouse gas in the earth. As that carbon is released into the atmosphere, it contributes to global heating, which means more fires, which means more carbon in the atmosphere, and more heat, and so on—feedback loops of devastation that are nauseating to contemplate. It’s in instances such as these, where the personal and the political intersect, that Klein’s writing is most moving. Her strident calls to action, written in ardent, rousing prose, make her a joy to read.

Taken together, what the pieces collected in On Fire reveal most clearly is that we’re in uncharted territory. As we move into a new era of climate consensus, the implementation of a Green New Deal will, as Klein writes, “necessarily be a work in progress”—one driven by the imagination of movements, unions, and scientists. Ultimately, in On Fire, Klein is more invested in what she describes as the “sense of possibility” that addressing the climate crisis presents than in getting down to brass tacks. Still, while a shift in the political narrative is not an end in itself, it’s hard to imagine any sort of successful movement toward decarbonization that doesn’t begin there.

Alex Lubben is a journalist in New York who reports on climate change and politics.