An Artist’s Revenge

“Scowling, he grumbled to himself: It’s no wonder the rich view artists as their pawns, and art as their plaything . . . No one makes real art anymore!”

The stories of Yiddish writer Wolf Wieviorka epitomized a generation of Polish Jewish immigrants to Paris—their struggles to make a living and find cultural grounding. Born in Żyrardów, Poland in 1896, Wieviorka published his first story in 1920, and immigrated to Paris in 1924, where he opened a restaurant for students in the Latin Quarter. His stories often sympathized with the poor and the working class, reflecting his Bundist politics. As Yitskhok Niborski, vice president of the Paris Yiddish Center–Medem Library, has written, Wieviorka’s “heroes are intellectuals and artists from the Yiddish milieu, parvenus without culture or soul, young people with revolutionary ideas, and gangsters straight from Warsaw.”

After years of scrambling to sustain a career, penning hundreds of articles for Yiddish newspapers around the world and serving as an editor of two Parisian Yiddish papers, Wieviorka received crucial support when a committee formed to support the publication of two volumes of his short stories. Mizrekh un mayrev [East and West] was published in 1936, and Bodnloze mentshn [People Without Land], a year later. Set in Paris or, occasionally, the shtetl, these stories explore nuances of power, class, and identity. His urban stories in particular resonate with contemporary conditions. Wieviorka fled Paris just before the Nazis invaded, eventually settling in Italian-occupied Nice. There, he and a handful of other Yiddish writers formed a literary circle, and worked to support other Jewish refugees. After several unsuccessful efforts to immigrate to the US, Wieviorka died on a death march from Auschwitz in 1945.

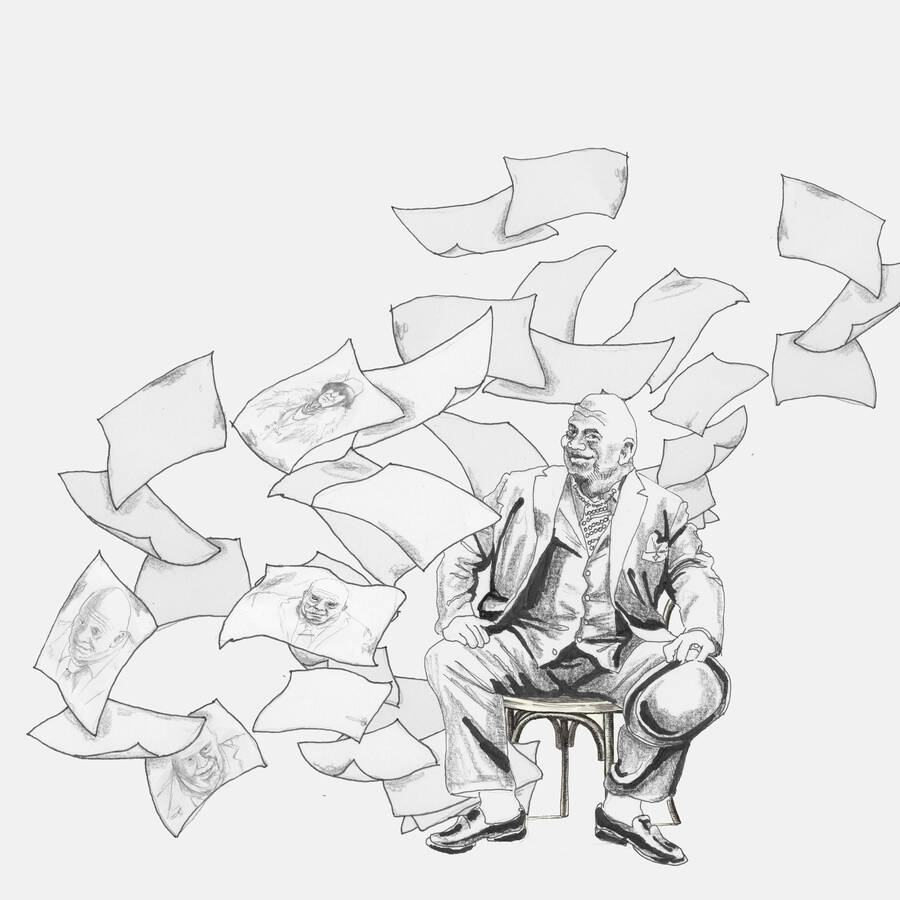

Rippling with homoerotic tension, the psychological thriller “An Artist’s Revenge,” originally published in Mizrekh un Mayrev in 1936, satirizes both the idealistic Montparnasse artist and the rich American tourist—pejoratively deemed “alrightniks” in Yiddish slang). Beneath the quick dialogue and mounting drama lies a sharp critique of each character’s ideals of masculinity and of art. Wieviorka’s stories bring to life the era that was the height of Yiddish culture in Paris—a city which, against all odds, remains an important center of Yiddishism today.

Perski walked by the coffeehouses on the Boulevard Montparnasse, his eyes searching and his brow furrowed in anger. He held a case of paints in one hand and an oversized sketchbook in the other. Dark thoughts consumed him.

The world might as well be a wasteland, he thought. No one understands art, let alone appreciates it. Today’s painters are sell-outs, and all they do is make portraits of the greatest sell-outs of all: the American Jewish nouveau riche, the “alrightniks.” These so-called artists sip their little cups of coffee and sell the portraits for a few dollars, using La Coupole cafe as their marketplace.

Perski dreamed of taking revenge on these artists—theoretically, of course. Scowling, he grumbled to himself: It’s no wonder the rich view artists as their pawns, and art as their plaything . . . No one makes real art anymore!

Finally, Perski sat down at a cafe and ordered a coffee, forgetting that he had no money to pay for it. He could only think about the bitter destiny of art and the moral decline of the artist. As he cursed this atrocity, Perski’s anger bubbled up: There’s no possible excuse, not one crumb of justification for today’s treasonous painters.

Of course, if Perski found himself desperately in need of cash, he probably wouldn’t refuse a few dollars from an alrightnik in exchange for a portrait—but he would never admit it. Instead, he raged at other artists and their shameless betrayal of art itself.

His eyes inflamed in fury, Perski noticed a strange businessman at the table across from him. The man had a stout body with a red, shiny, bald head perched on top like a bowling ball. His beady eyes were barely visible from their sunken position in his fleshy face.

Perski looked closer and saw how these small eyes, nestled in folds of skin, sparkled nevertheless. Suddenly, the businessman met Perski’s gaze with a condescending glance. This glance made Perski’s frustration boil over, and his own eyes blazed with venomous hatred. I am sick and tired of greedy businessmen and capitalists, and I must exact revenge on this man. I am an artist, and my weapon is paint—and a brush!

While Perski was lost in thought, the businessman looked at him again. Perski observed the man’s turkey neck, which almost concealed his flashy necktie pin. As Perski studied his plump lips and the nape of his meaty neck, an idea came to him like a flash of lightning: He would sketch him and call it “The Art Patron.” Perski opened his case of paints, found a blank page in his sketchbook, and started to draw.

The businessman noticed. His small eyes began sparkling anew, and then he squinted. He’s making all kinds of assumptions, Perski said to himself: he thinks I’m a starving artist looking to earn a few bucks off his portrait.

Indeed, the businessman was intimately familiar with these kinds of exchanges. He had already collected no fewer than ten portraits from Montparnasse artists. Everyone knows the choreography: First the artist sketches a tourist and then approaches with an offer. The parties negotiate, but always settle on two dollars, the universal fair price.

A select few artists, however, play by different rules—they never approach the customer. They remain seated and act as if they’re drawing only for their own benefit. They wait patiently for the tourist to approach and ask to buy the sketch, hemming and hawing until the tourist begs. This kind of artist only accepts ten dollars, or more, for a picture.

The businessman preferred the artists who didn’t play games and only charged two dollars. To him, their pictures were more beautiful—they flattered their subjects and smoothed over imperfections. However, he had learned that the art he found unremarkable was often considered important by the experts. And this art was more likely to surge in value, since the artist could become world-famous.

The businessman smiled to himself and assumed an uncomfortable but dignified pose so the portrait would show off his importance. Out of the corner of his eye, he watched Perski. Perski studied his paper so intently that his eyes seemed closed, save for furious glances at the businessman. The businessman, in turn, stole glimpses at Perski from his own contorted position.

Look at the show he’s putting on for me, thought the businessman, all to trick me out of a few dollars, as if I were a fool. I know all his next steps. When he’s done with the sketch, he’ll look it over and nod approvingly. Then he’ll set it down and walk away casually, trying to make me run after him asking to buy it. Oh, I know how they play the game, these artists who act like beggars. Ha! If only he knew that I’m in control. I’ve been tricked before, but not this time. This time is different. I’ll even smile for the picture—won’t that look nice?

As he grinned, the businessman plotted: If I want to buy the sketch, I won’t beg for it. I will wait patiently until he starts pleading, no matter how long it takes. I’ll be calm, cool, and casual. As the businessman fantasized, his smile made his face even rounder and redder. If, and only if, he asks me to buy it, I will not pay a cent over five dollars!

At the same time, across the room, Perski smiled back at the businessman. The businessman’s grin was a miracle, a gift from God. He sketched frantically to capture it. With this final touch, the sketch was becoming exactly what Perski had hoped for: a glowing, cackling Satan. The businessman had unknowingly handed Perski the perfect image of the figure he cursed incessantly: “The Art Patron.”

Perski worked feverishly—for him nothing else existed but the body of the businessman, this worthless person with a wide smile and fleshy plumpness. I must capture every aspect of this alrightnik’s atrociousness, hatefulness, emptiness. The drawing must convey it all!

The businessman observed Perski’s obsessive sketching and basked in the attention. But as he considered him, he stopped smiling. Though he loathed to admit it, he had begun to respect this artist and even felt curious about him. When Perski closed his notebook and packed up his paints, the businessman forgot his vow to feign disinterest. He forced a smile, different from the one before, and bolted toward Perski.

“May I take a look, please?” the businessman cooed.

Without a word, revenge burning in his eyes, Perksi shoved the notebook under the businessman’s nose.

The businessman gasped in horror. Terror seized his body. Is this what I look like? he thought, recognizing his big forehead and bald head, his small eyes and the surrounding fat, his chin—even his smile. It looks like me, but it is also . . . It cannot even be a person. It is a monster, a freak. What is this bizarre artist trying to do with this sketch? What kind of art is this?

As the businessman seethed in disgust, Perski slid the notebook away and flicked it shut. “I look like this?!” the businessman said.

“To me, yes.”

“And why would I need this? Why have you painted a portrait of such a horrific person?!”

Perski didn’t answer and began packing up his belongings.

“Wait—I need to buy it! How much?”

At that moment, Perksi remembered that he had not paid for his coffee—and he could not pay for it. The anger he had channeled into this sketch came roaring back, and he replied definitively:

“One hundred dollars.”

“One hundred dollars?! I could ask a better artist than you to make beautiful portraits for ten dollars!”

“Well, I did not make this sketch for you, but for me. It’s not even for sale,” Perski replied.

They both simmered in anger. The businessman shook his fist, but he knew Perski could walk away at any moment. His worst fear would be for someone else to own this horrible portrait—he could imagine no greater shame. He snatched a one-hundred-dollar bill from his pocket with his shaking, sausage-like fingers and threw it at Perski.

“For you,” he barked.

Perski slowly ripped the drawing out of his sketchbook and flung it at the businessman. “For you.”

The businessman grabbed the picture and tore it down the middle, then again, and again, until there were one hundred pieces, which he arranged into a neat pile.

“For you.”

Perski took the one-hundred-dollar bill, held it in his hands, and did the exact same thing. As he ripped each shred, he repeated: “For you, for you, for you.”

And then, as if nothing had ever happened, Perski stood up and walked away, off to find another alrightnik to pay for his coffee.

Wolf Wieviorka (1896-1945) was a Polish-born Yiddish writer, an active member of the Parisian Yiddish literary scene, and the author of two collections of short stories and countless newspaper articles.

Sarah Biskowitz is a Jewish cultural activist and feminist educator. She works at the Yiddish Book Center as the 2021–2022 Richard Herman fellow in bibliography and exhibitions.