An Answering Art

What would an English translation of the Hebrew Bible look like if we could take off the Christ-colored glasses?

Discussed in this essay: The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary, by Robert Alter. W. W. Norton & Company, 2018. 3500 pages.

The Art of Bible Translation, by Robert Alter. Princeton University Press, 2019. 152 pages.

A profile of Alter that ran in The New York Times Magazine last December described his project as “A New Hebrew Bible to Rival the King James.” I took this to suggest antagonism and restoration. After all, most English-language Bibles throughout history have been commissioned by and for Christians. The Hebrew is therefore viewed through the distorting lens of that theology, with its tendency toward abstract concepts like “salvation,” its a-Judaic emphasis on the afterlife, and, of course, its need to make the Old and New Testaments ultimately reconcilable, which often means forcing the original text to bend so that the belated one won’t break. (The very terms “old” and “new” are intrinsically Christocentric. “Testament” is troubling, too, with its emphasis on orality and fact-finding over artistry and intent. Alter never uses these terms; I won’t be using them again.) What would an English translation of the Hebrew Bible look like if we could take off the Christ-colored glasses through which we’ve long been obliged to read it?

ALTER NEVER INTENDED to take on this task any more than Sarah set out to become a mother at 90. He says as much in the “Autobiographical Prelude” to The Art of Bible Translation, a slender, passionate, pugnacious monograph that serves as both introduction and paratext to Alter’s Hebrew Bible. This book is Alter’s explanation of what he did, how he did it, and why he bothered. Divided into short, focused chapters on such subjects as syntax, word choice, “sound play and word play,” rhythm, and “the language of dialogue,” it also serves as a handy survey of biblical style: the range of rhetorics, literary devices, poetic forms, and modes of attention that animate the texts.

A scholar of comparative literature and modern Hebrew, Alter first studied ancient Hebrew for pleasure, and later to augment his fluency in the modern version of the tongue. He found himself drawn to the style of biblical poetry—particularly its deployment of repetition, punning, rhyme, and parataxis—and to “the terrific compactness” of biblical narrative. Early on in The Art of Bible Translation, Alter presents something like a thesis: “the literary style of the Bible in both the prose narratives and the poetry is not some sort of aesthetic embellishment of the ‘message’ of Scripture but the vital medium through which the biblical vision of God, human nature, history, politics, society, and moral value is conveyed.”

Alter furnishes his Bible with heaping helpings of historical context and supporting arguments for his choices as a translator. There are chapter-length introductions to each volume of The Hebrew Bible and to each book contained in each volume, and substantive footnotes adorn every page. Alter is candid about the limits of what can be known, or even confidently speculated, about ancient Hebrew and the lives of the people who spoke and wrote and thought and worshipped in it, but he always provides as much information as possible, even when that means second-guessing himself or pointing to a blank spot in the historical or linguistic record. The footnotes compete with the body text for page space, which encourages a split-screen reading style that divides the attention. Moreover, the notes feel forbidding, like so much homework, which undermines the immersive literary quality of the experience. I’m glad they exist, but I wish they had been relegated to endnotes, or even to a separate volume, where I could refer to them only as needed. The vast majority of us, after all, are not Bible scholars, translators, or rabbis. Hell, a lot of us aren’t even sure what it means to be Jewish, much less where a Bible might fit into whatever frameworks we’re working toward (or, quite possibly, resisting). I was bar mitzvah’d in 1995 and have hardly seen the inside of a sanctuary since. Most of the time, my relationship to Judaism—and to Jewishness—is that of the child at the seder who does not know how to ask. The promise of this Bible, then, is not that it will answer my questions, but rather that it might help me pose them.

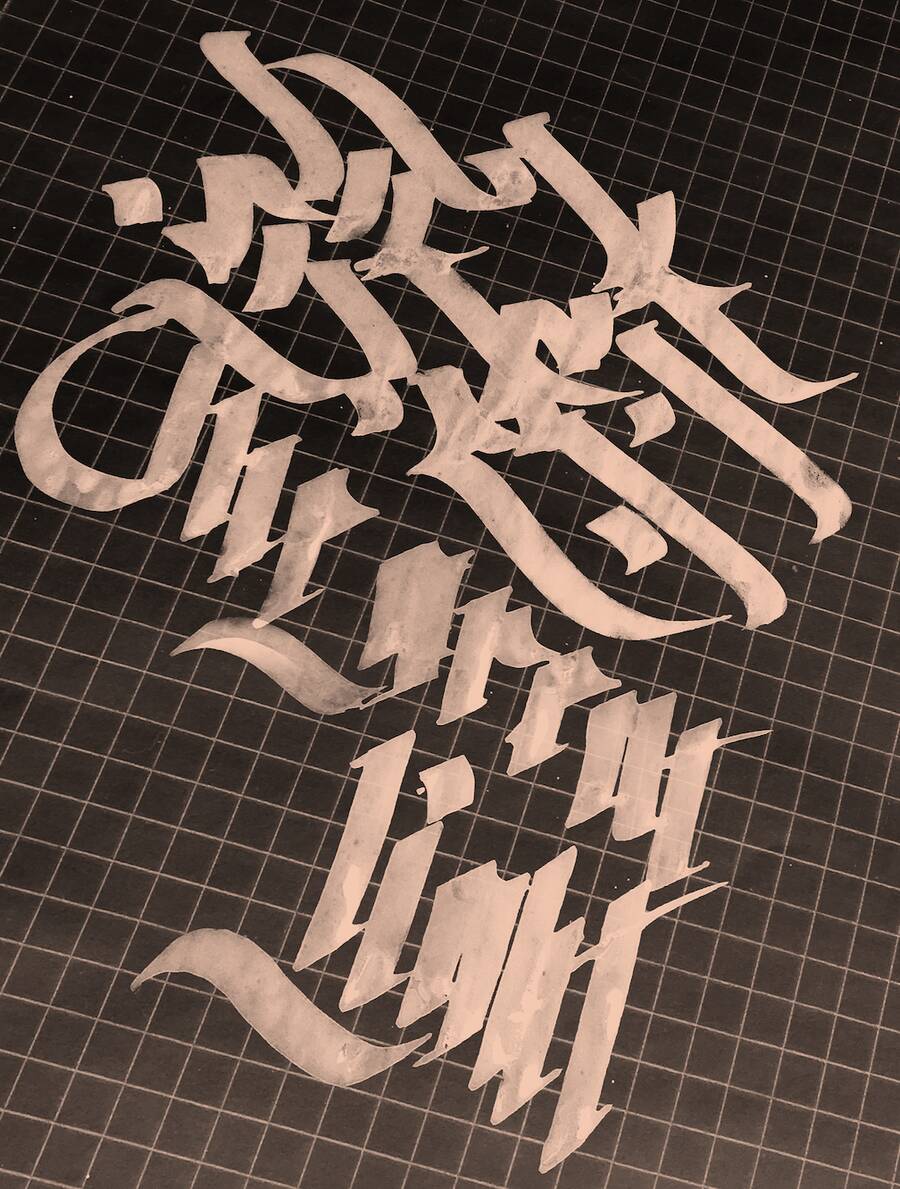

A/Alef by Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson

“THE BIBLE ITSELF does not generally exhibit the clarity to which its modern translators aspire,” Alter writes in The Art of Bible Translation. He admires the King James Version (KJV) because it embraces that difficult truth. Though he admits that its grasp of the Hebrew occasionally falters and that it sometimes gets tied up in theological knots, thanks to the imposition of Christian concepts on a Jewish text that cannot easily accommodate them, Alter’s respect for the KJV is hard to overstate. He regards it as an invaluable cultural artifact and an effectively inexhaustible work of literature. He wrote a whole book—Pen of Iron (2010)—about the translation, its influence on the English language in general and on American literature in particular. He praises its overall accuracy and, most crucially, its attention to style—which is to say, its treatment of biblical literature as literature. There are significant differences between the KJV and Alter’s own translation, but the “rivalry” declared in the Times Magazine profile turns out to not really exist.

The true object of Alter’s enmity—the wrong he wants desperately to correct—is the proliferation of “modern English” translations that, in his view, deliberately evacuate the text of nuance and depth in the interest of presenting something “accessible.”

He elaborates:

The Hebrew writers reveled in the proliferation of meanings, the cultivation of ambiguities, the playing of one sense of a term against another, and this richness is erased in the deceptive antiseptic clarity of the modern versions . . . Not only do the modern translators lack a clear sense of what happens stylistically in the Bible, but also their notion of English style, its decorums and expressive possibilities, tends to be rather shaky. The essential point of all this is that the Hebrew Bible by and large exhibits consummate artistry in the language of its narratives and of its poetry, and there must be an answering art in the translation in order to convey what is remarkable about the original.

Over and over in The Art of Bible Translation, Alter calls out flaws or outright flubs in popular 20th- and 21st-century translations such as the New English Bible, the Revised English Bible, the New Jerusalem Bible, and the Jewish Publication Society (JPS) Bible. The index entry for “modern translators’ problems” gives a good taste, and makes for a lovely found poem in its own right:

avoidance of anthropomorphism

condescension

diction lapses

etymology overreliance

explanatory impulse

failure to consider context

failure to represent Hebrew literary structures

literary and cultural limitations

mistranslations and howlers

obtrusively modern language

parataxis avoidance

philological overreliance

rhythm avoidance

sex and body functions avoidance

The JPS is regularly scolded in a way that I can only describe as familial: the kind of beleaguered bitterness you reserve for a hopeless cousin—the one who skipped coming home for the High Holidays again this year and is always breaking poor Aunt Ruthie’s heart. Alter describes the JPS rendering of Genesis 1:16, in which God makes the sun and the moon on the fourth day of creation, as “painfully inept” for its translation of the Hebrew “memshelet” as “dominate”: “the greater light to dominate the day and the lesser light to dominate the night, and the stars.” Alter’s objections are both aesthetic (“‘dominate’ entirely wrecks the beautiful cadence of the Hebrew”) and semantic. He’s troubled by the translators’ “manifestly tin ear to the connotations” of “a term appropriate for political contexts—as, for example, in a sentence such as ‘The Soviet Union dominated the smaller states of Eastern Europe’—or for sexual perversion with whip and boots as accoutrements.”

The KJV translates Genesis 1:16 this way: “And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also.” Despite getting a bit choppy at the end, this has a nice cadence to it, particularly in the rhythm-and-sound driven middle clause, “the lesser light to rule the night.” Alter allows that “to rule” is a common and legitimate rendering of “memshelet,” more plausible than either the JPS’s “to dominate,” or other modern translators’ “to govern,” which, as Alter points out, “suggests administration through vested power,” a political concept that would have been largely unfamiliar to the people of ancient Israel.

In the end, Alter selects “dominion.” Initially, I found this surprising, given its closeness to the JPS choice. But the more I thought about it, the more I saw the way that his word resonates in an entirely different register, despite the sonic similarity and common root. Here’s Alter’s full rendering: “And God made the two great lights, the great light for dominion of day and the small light for dominion of night, and the stars.” The shift from greater/lesser to great/small has removed the whiff of competition from what is meant to be merely descriptive. At the same time, the rhythmic consistency of his “small light for dominion of night” is commensurate with the KJV’s “lesser light to rule the night.” The shift from “greater” to “great” sharpens the affinity between the long “a” in “great” and the same sound in “day,” a gesture which is repeated in the long “i” of “light” and “night,” providing sonic balance to the line and using tonal repetition to reinforce the repetition of “dominion,” and thus further underscore that the stars are established outside of the sun/moon binary. Even the most minute textual decision has enormous ramifications, and so deserves to be considered seriously and with discernment.

Alter, while emphatic about his choices, emphasizes that this is what they are: choices. They are, therefore, subjective, contingent, and fallible. “[T]ranslation,” Alter writes, “often involves painful compromise—you gain something through the loss of something else.” Each reader will inevitably develop her own sense of the cost of these myriad trade-offs, and use her own judgment to determine whether they were worth it. A bit of accuracy might be worth what it costs in poetry, but what about the usage-history of an oft-quoted phrase? To sever that connection is to lose something substantial yet difficult to quantify. Still, there’s something liberating about reading a Bible largely free of the future history of its own incalculable influence.

Take Ecclesiastes 7:4 (for Alter, Qohelet 7:2—he eschews the Greek word in favor of leaving the Hebrew untranslated, as its meaning has been lost to time). In the KJV: “The heart of the wise is in the house of mourning; but the heart of fools is in the house of mirth.” In Alter: “Better to go to the house of mourning than the house of carousing.” I do miss the hearts of the wise and of fools, but I’m glad to have lost the anachronistic association with the Edith Wharton novel, which is always what pops into my mind when I read the words “the house of mirth.” It’s also nice to be able to read Psalm 137 (“By Babylon’s streams, / there we sat, oh we wept” etc.) without hearing it sung in Bob Marley’s voice, or Bradley Nowell’s. Changes like these, small as they are, speak to what I find most valuable about Alter’s project: the making new (in the Modernist sense) of a text that, in its incarnation as the KJV, is so totally enmeshed within our culture and language that it is nearly impossible to encounter it directly, without the mediation of a thousand thousand previous, derivative encounters.

I love the new Genesis 1:1, which gains astonishing velocity from shedding that old throat-clearer, “In the beginning,” and restoring its parataxis: “When God began to create heaven and earth, and the earth then was welter and waste and darkness over the deep and God’s breath hovering on the waters, God said, ‘Let there be light.’” The passage pulses with the energy of the Creation that it describes, building like music toward the moment of crescendo, when God breaks the silence of eternity and breathes the world into being. Notably, this inaugural act is already an act of translation. God chooses language as the medium through which to realize His vision, to render chaos readable as the text we call reality. The first gift of creation is the gift of language no less than it is the gift of light.

It is strange—and exciting—to read a Bible that does not contain the word “soul.” Alter prefers “life-breath,” “breath,” or even “neck” (used metonymically), any of which can be contextually appropriate renderings of the Hebrew word “nefesh.” I believe Alter when he says that the ancient Hebrews had no concept of the “soul” as we now tend to understand it, i.e., as an eternal persistent consciousness discrete from our bodily selves. Alter considers this to be an explicitly Christian notion. But doesn’t “life-breath” have many of the same connotations—right down to the airiness of spirit, the vitalizing ghost—while sounding clunkier than “soul” does? On the other hand, there’s something strikingly Jewish about the earthiness of “life-breath” and the way it restores attention to the body, suggesting that you can’t have one without the other. When the breathing stops, the ghost goes, but it doesn’t go to Ghostville—it’s just gone.

If the loss of “soul” is another of these “painful compromises,” there are moments when that pain becomes acute. Consider the opening of Job 10.

Alter: “My whole being loathes my life. / Let me give vent to my lament. / Let me speak when my being is bitter.”

KJV: “My soul is weary of my life; I will leave my complaint upon myself; I will speak in the bitterness of my soul.”

Alter’s version may well surpass the KJV in capturing the rhythm and sonic play of the original, but “let me give vent to my lament” sounds like open mic night. And accuracy is, in any case, a poor substitute for the transcendent heartbreak and poetic splendor of “My soul is weary of my life.” A friend of mine quotes this verse in an essay he wrote about the death of his son. When I heard him read that essay before an audience, his voice broke when he spoke the words. He began to sob, and the whole room wept with him. I have never experienced anything quite like that before, and I believe it was the power of the line itself as much as the context in which it was quoted that allowed him—and us—to be shattered by it, and to share, if only for a moment, his sorrow with him. What is a Bible for if not to help us help each other bear what is unbearable? “My whole being loathes my life” would have buckled beneath the weight.

IT IS ALTER’S CONVICTION and also mine, that the truest measure of the value of a work of literature is its ability to sustain, withstand, and repay attention. I spend a good portion of my days, which are “like grass” (Psalm 103) and surely shall “flee like a shadow” (Job 14), trying to explain this to creative writing students. This work often leaves me crying out, along with Psalm 22, “My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?” (Notably, this is the verse that Jesus quotes while being crucified.)

I’ve begun to fantasize about assigning The Art of Bible Translation instead of whatever benighted craft book is in vogue this season. Of course, I don’t expect my students to write Bibles. I don’t expect myself to write one either. But I think our time would be better spent with a model of profound reverence for language—which is capable of so much more than we tend to allow for or even imagine possible—than with the literary equivalent of directions for assembling Ikea furniture.

Prayer is a form of attention. That’s not news, or it shouldn’t be. What gets said less often is the inverse: Attention is a form of prayer. What do we pray for when we pay attention? I pray, among other things, for “rescue,” which is the word Alter uses for “yesh’ua” in lieu of the KJV’s “salvation,” which really does seem to me like a Christian concept: abstract, static, heavenly. The ancient Jews—much like the present-day Jews—are concerned with something rather more urgent and concrete. Our suffering is in this world, and it is in this world that we would like to see it alleviated.

So when I blow “the horn of my rescue” (Psalm 18), what exactly is it that I’m hoping to be rescued from? From the debasement of language and destruction of nuance that infects common discourse and even private thought, as though the culture’s ultimate goal were the eradication of interiority itself. (I’d also like to be rescued from climate change and AIPAC, but I don’t think we’re going to be able to pray our way out of those.) I pray for rescue from this feeling of being cut off from history, from the fullness of my intellectual, spiritual, and literary birthright, however fraught it may prove to be. The loss of this amounts to a loss of life-breath—a loss, if you’ll permit the infelicity, of soul—and to have it restored is a gift. In setting before us this vast reservoir of agon and wisdom and pleasure and ambiguity, Robert Alter has given us something worthy of our best attention. May we find it in ourselves to pay it. He has answered a question I did not know how to ask.

Justin Taylor is the author of three books of fiction and a memoir, Riding with the Ghost, forthcoming from Random House in 2020. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, and The Sewanee Review. He lives in Portland, Oregon.