Activestills and the Making of a Decolonial Archive

Members of the Israel/Palestine-based photo collective explain their approach to their work.

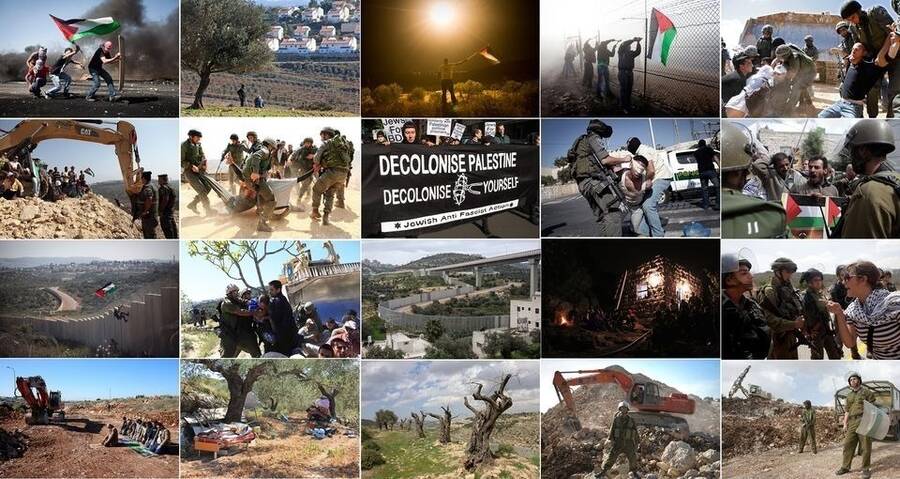

Since 2005, the Activestills photo collective has published nearly 50,000 images documenting culture, protest and repression in Israel/Palestine, capturing everything from Tel Aviv protests against the deportations of asylum seekers to Israel’s destruction of Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem to holiday celebrations in Gaza.

As part of our weekly Tuesday News Bulletin, Jewish Currents is publishing a photograph taken by members of Activestills every week, providing a lens into the ongoing dispossession of Palestinians as well as the resistance from the river to the sea. The photos will also be featured on this website’s homepage, and an archive will also be viewable here.

To introduce readers to Activestills, Jewish Currents interviewed two members of the collective: Palestinian photographer and journalist Ahmad Al-Bazz and US-based Israeli photographer Shachaf Polakow. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Alex Kane: What are the politics behind Activestills’s work, and how does that differentiate Activestills from other photographers working in Israel/Palestine?

Ahmad Al-Bazz: The main difference between us and other photographers is in the political framework. We are a group of activist photographers who use photography to serve the struggle for liberation and decolonization in Palestine/Israel. These days, even in the most progressive conversations, people think the problem in Palestine/Israel starts in 1967, not in 1948. They see Israel as a normal country making some mistakes outside its territory.

We see Palestine/Israel as a classic colonial situation, and we highlight its problematic aspects as they appear everywhere between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. There are colonial problems in Jaffa, known today as Tel Aviv, and others in Nablus. Saying that one part is occupied and one is not is arbitrary. Take the issue of refugees, for example: Each town within the 1948 territory in present-day Israel is a settlement built on the lands of a population that now lives in refugee camps in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and other places. This is how we approach the whole country: showing continuities between colonization within the 1948 borders, colonization in the West Bank, and the blockade of Gaza. It’s never a “conflict” between two equal parties. The approach is as important as the photo itself. Without it, photos could be misinterpreted.

Shachaf Polakow: As photographers, we have the power to show evidence of settler-colonialism, not just to discuss it theoretically. We work with the understanding that each photographer in our collective holds vastly different privileges, especially the Israelis, who can travel much more easily than other photographers, and especially Palestinians. We have a photographer in Gaza who can’t come see us in person, for instance. Together we are creating an archive that by itself serves as a political tool, one that is used by activists and communities.

AK: What does it mean that Activestills is a “collective”? How do you make decisions?

AAB: We’re not a traditional NGO. We’re simply a group of people who share the same political view on Palestine/Israel, and use the same tool. We established a collective because working collectively is more powerful than working individually.

It’s a horizontally structured collective. There is no boss, no one assigning tasks. Each one of us decides to go wherever he or she wants to go, motivated by a belief in the importance of covering that issue.

SP: We work together without foregrounding individual photographers. This collective approach helps to strengthen both our aesthetic editorial choices and to constantly expand our political framework.

AAB: I’m really happy about the model that we’ve managed to create and sustain. It’s been running since 2005. We don’t have too many financial responsibilities. We don’t have an office. We all have work here and there, so we can support ourselves. At the same time, members dedicate tons of hours of free time to the collective every month.

AK: Are people paid for their work on the collective?

SP: No. We base the workload on our availability. We do try to find funding for big projects. And any money we do get, we might do something like buy spare parts for our photographer in Gaza.

AK: As you’ve said, Activestills was established in 2005. What’s the most important thing you’ve accomplished since then?

AAB: This is a critical question. Likely every member of the collective has asked themselves this question after finishing a day of shooting: What is the result? What have I done? The difficult thing about media is that sometimes you don’t see the result. The work is mainly about exposing people to injustice, raising awareness, but it’s impossible to know what is happening inside the mind of someone who has seen our pictures. Sometimes it’s a bit discouraging.

Of course, we don’t expect to upload a photo one day, and for circumstances to change the next. There needs to be patience. It’s a long-term effort, like the struggle against colonization in this country as a whole. Everybody has been trying to do something differently for at least the last 74 years. Nothing has changed yet. But it’s a collective effort, everyone working against the system with what they’ve got.

SP: I think one way to define success is the fact that we’re still working together after 15 years. Personally, I believe that the archive has the power to create an anti-colonial narrative, which was part of the impetus for the collective in the first place—to counter mainstream narratives about Palestine and Israel in the media and in political discourse. The nearly 50,000 photos in our archive documents that struggle.

We challenge each other. This week we had a heated conversation about the caption for one photo. But the fact that we can actually have that conversation—Palestinians and Israelis and internationals—without falling apart is, in many ways, a success in itself. We understand that we are passionate about these issues because we believe in the same thing.

There’s so much despair about what the future holds. But the fact that we can continue to create art and photography that hopefully contributes, one day, to the liberation of Palestinian people, and equality for everybody between the river and the sea, is something we shouldn’t take for granted. Activestills is one of the few spaces that is generating a conversation about the kind of future we want. That’s quite a victory.