Abortion Without Apology

In her new book, Jenny Brown urges feminists to return to a more radical mode of reproductive rights activism.

Discussed in this essay: Without Apology: The Struggle for Abortion Now, by Jenny Brown. Verso, 2019. 208 pages.

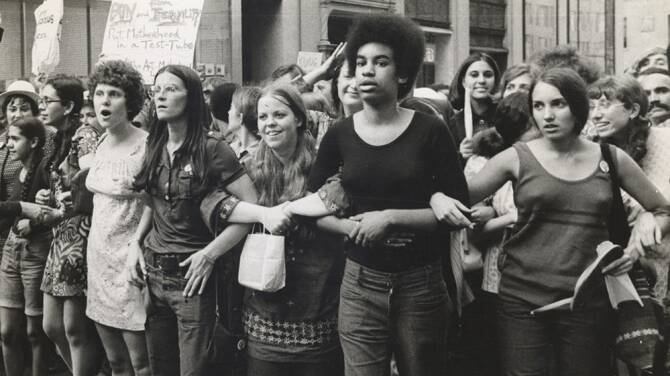

IN 1969, THE NEW YORK CITY HEALTH DEPARTMENT hosted a panel of 15 speakers—14 men and one nun—to discuss the possibility of creating narrow exceptions to New York’s strict anti-abortion laws for women who had been raped or faced other special circumstances. In the midst of the proceedings, an action group from the feminist organization New York Radical Women stood up to dispute the event’s very premise. The protesters shouted that they did not want to bicker over exceptions to sexist laws that controlled women’s lives; they wanted full reproductive freedom. A month later, the action group—now known as Redstockings—held its own hearing. There, 12 women, addressing an audience of several hundred, talked about their abortions. This abortion speak-out, the first of its kind, helped draw conversations about abortion, long shrouded in secrecy and shame, into the public sphere.

Feminist labor organizer and author Jenny Brown opens her book Without Apology: The Struggle for Abortion Now with this history in order to reacquaint us with the boldness of an earlier moment in reproductive rights activism. Brown contends that, unfortunately, the prevailing arguments for abortion rights in circulation today in some ways have more in common with the timid, equivocal discourse of the New York City Health Department hearings than with the straightforward demands of the feminist disruptors. These arguments—often developed by professional political strategists and nonprofit leaders—rely on rhetoric that, in Brown’s view, actually serves to reinforce the stigmatization of abortion. The common talking point that birth control is not abortion, for instance, falsely exceptionalizes the latter; even grounding abortion rights in the right to privacy, as per current American legal frameworks, only reinforces the notion that women should not discuss their abortions in public. For Brown, the prevalence of such weak rationales points to a deeper problem: most feminists have all but given up on the idea that they can change anyone’s mind about abortion.

Brown, on the other hand, does not accept the premise that opinions are fixed. Instead, she posits that through the kind of unflinching messaging, storytelling, and organizing Redstockings performed 50 years ago, feminists can destigmatize abortion and expand abortion rights. Without Apology makes this case as it covers a range of issues related to reproductive rights, including the successful 2018 campaign to legalize abortion in Ireland and Brown’s own work expanding access to the morning-after pill in the United States.

Brown’s first chapter, “The Basics,” describes in clear, nearly clinical prose what happens during a vacuum aspiration procedure, the most common type of abortion. After decades of the culture wars that have freighted abortion with emotion and vitriol, it’s refreshing to see the safe, brief procedure demystified. Brown, a sober and knowledgeable narrator, is skilled at cutting through the drama that usually accompanies the issue of abortion. For years, pro-choice groups have emphasized horrible circumstances—rape, poverty, fetal deformities—to curry sympathy for abortion rights. In reality, Brown writes, many abortions occur for reasons that are not especially dramatic: a condom broke, or a woman already had the children she wanted. These mundane circumstances don’t have to be contorted in order to justify the basic principle that no one should be forced to carry a pregnancy and deliver a baby.

In the ensuing chapters, Brown takes the reader through a succinct, fascinating history of abortion, its criminalization, and the underground network of abortion providers in the pre-Roe v. Wade US. Throughout the 18th and most of the 19th century, abortion was widespread and prohibited only after “quickening,” when a pregnant woman could feel the fetus stir. Abortion was first prohibited nationwide in the 1870s with the passage of the infamous Comstock laws against obscenity. Without Apology’s grim account of the century of illegal abortions that followed will surprise even readers well aware that women died trying to end their pregnancies. Brown divulges, for instance, that doctors who provided clandestine abortions often feared their patients would be interrogated by police and give up the doctors’ names. As a result, abortion seekers would sometimes be met by an intermediary, blindfolded, taken to an undisclosed location, and given an abortion by a practitioner who would not disclose their name, before being deposited—still blindfolded—back on the street.

Brown also presents readers with a tradition of unapologetic feminist organizing that, she argues, today’s activists should replicate. Starting in the late 1960s, the more radical wing of the women’s liberation movement pushed to fully repeal, not just incrementally reform, abortion bans. Organizers combined this goal with other ambitious demands—they pushed for 24-hour company- and state-supported childcare, lifelong healthcare supported by taxes, and an end to the oppression of women of color—and bold tactics for achieving them.

Brown contrasts radical feminist aims, rhetoric, and tactics with those of the professional feminist movement steered by more cautious outfits like NARAL—originally the “National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws,” though the meaning of the acronym has shifted over the decades—and Ms. Magazine. Brown cites the late feminist liberation leader and writer Ellen Willis, who accused such mainstream groups of promoting a “mushy, sentimental idea of sisterhood” wherein “disparities of power, economic privilege and political allegiance are glossed over”; ultimately, Brown argues, these brand-name entities diluted the feminist movement’s potential for building legal, political, and cultural strength. That abortion and even contraception access are at risk in states across the country provides plenty of evidence to support Brown’s thesis that mainstream women’s organizations did not choose a winning strategy.

Brown’s critique of mainstream pro-choice messaging, in tandem with her alternate vision for feminist organizing, powerfully synthesizes many concerns of reproductive justice advocates working on the ground nationwide. But when Brown turns her attention to recent examples, her analysis sometimes becomes thin. One instance she presents as a failure of messaging concerns a campaign against a 2014 anti-abortion Tennessee ballot initiative. Anti-abortion activists ran ads emphasizing the need to restore the voice of Tennesseans and reclaim the right of the people to restrict abortion. Abortion rights campaigners countered with ads emphasizing worst-case scenarios—rape, diagnoses of fetal deformities, life endangerment—and the right to privacy. Building on her book’s central thesis, Brown points out that these arguments do nothing to bolster the public’s sense that women need abortion rights to be free. “Abortion is still legal on demand in Tennessee, and yet somehow we’re transported back to 1969,” she writes of the pro-choice messaging focused on privacy.

What Without Apology is missing is everything contained within that somehow. Tennessee is a solidly Republican state where polls consistently show that the majority of voters believe abortion should be illegal in most or all cases; it’s therefore not difficult to guess why strategists trying to keep abortion legal in the short term would center arguments for privacy and against government intrusion in their messaging, even if those arguments are corrosive for feminism in the long term. Likewise, Brown examines a series of Planned Parenthood advertisements that ran in 2015 and emphasized the flu shots and cancer screenings the organization offers, while omitting any mention of abortion. She uses these ads, too, as examples of how mainstream pro-choice organizations are surrendering opportunities to change our culture by boldly proclaiming support of abortion rights. Brown mentions as an afterthought that the ads ran shortly after a propaganda campaign that smeared Planned Parenthood. But she does not describe how, around that same time—and as a result of that propaganda campaign—12 states and Congress opened investigations into Planned Parenthood, threatening and in some cases ending its funding for providing preventative care, while states across the nation introduced hundreds more anti-abortion bills, many of which prohibited abortion providers from “selling dead baby body parts.” Within that fuller context, which Brown skips over, it’s easier to understand why Planned Parenthood would run ads positioning itself as a provider of flu shots and cancer screenings.

Without Apology derives strength and clarity from its omission of gruesome details about the relentlessness of the anti-abortion movement, which often dominate public conversations about abortion even within the left. It’s invigorating to read a book about abortion politics that makes feminists the protagonists. In this sense, Brown’s book performs the proactive, rather than reactive, stance it advocates. Yet Brown also weakens her own case by glossing over the factors behind many feminists’ choice to take a defensive strategy instead. There is no getting around the tension between the short-term goals of defeating an anti-abortion ballot initiative or keeping a clinic open, and the long-term goal of shifting our culture; indeed, this tension only underscores the need for feminist activism that intentionally takes aim at the broader cultural conversation. Precisely because abortion providers and pro-choice political groups are perpetually locked in short-term battles, feminist organizers must commit to pushing for long-term cultural change.

Planned Parenthood and feminist activists have different incentives and goals, even if their values and aims sometimes overlap. Planned Parenthood is going to make decisions that allow it to keep operating, as are the ACLU, NARAL, and other brand-name interest groups. But acknowledging those groups’ need to survive in the short term only supports Brown’s argument that feminist activists must become more assertive, better organized, and emphatically unapologetic. In coming years, abortion providers and pro-choice political groups will face increasing short-term dilemmas. Meanwhile, feminist activists can and must make decisions and take risks that change the cultural and political conversation about abortion. With a conservative majority in the Supreme Court, the federal courts packed with Republican appointees, and many state assemblies controlled by anti-abortion lawmakers, Without Apology delivers a critical message. In the prescient words of Redstockings leader Lucinda Cisler, “To abandon the political field is to leave it to the fervent, well-funded anti-abortion forces.”

Meaghan Winter is the author of All Politics is Local: Why Progressives Must Fight for the States.