You Can Give This to Your Gentile Friends

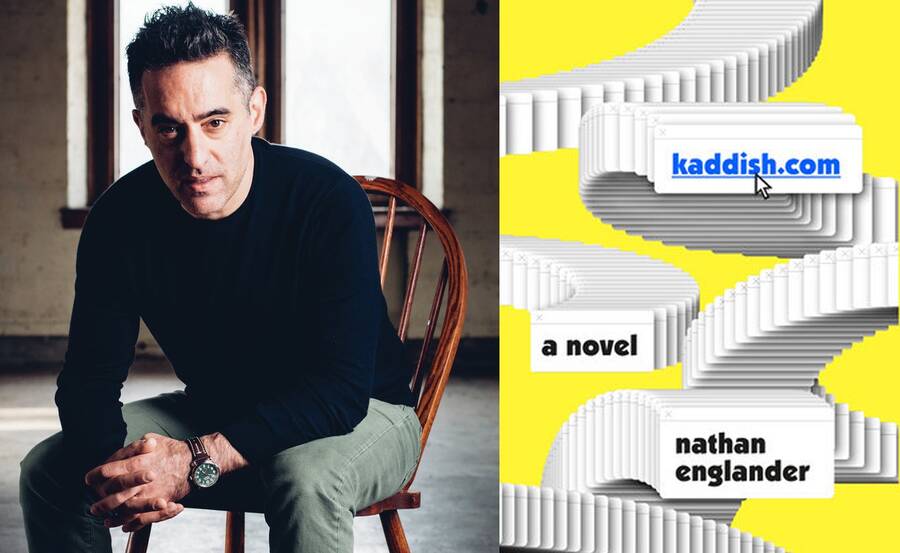

Nathan Englander talks about God and the internet in his new novel kaddish.com.

Nathan Englander is the author of the story collections For the Relief of Unbearable Urges, winner of the PEN/Malamud Award, and What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank, as well as the novels The Ministry of Special Cases and Dinner at the Center of the Earth. His third novel, kaddish.com, excerpted in Jewish Currents, is about a lapsed Orthodox Jew named Larry who pays an internet service to perform the required year-long Kaddish prayers upon his father’s death.

Nathan and I discussed his new novel over knishes at the Russ and Daughters Café at the Jewish Museum.

Lauren Goldenberg: Why this particular novel now?

Nathan Englander: Well, it’s 20 years since the publication of my first book, For the Relief of Unbearable Urges. I’d been writing Dinner at the Center of the Earth, trying to find a way to explore the Israel/Palestine conflict and my heartbreak over the end of the peace process. I’m writing this book that is this literary, political thriller, and also a magical realist history of Israel, and also a love story that has like seven timelines in five different countries, and I’m thinking, how did I get here from there? I thought: If I can do this now, I want to bring who I am now as a writer back to where I began, to the sacred and profane, to that gray space which still runs through all my work.

It’s been about ten years since my father passed away. I’m a dad now and my daughter is just at that age where I’m like, “Oh, I guess we’re Jews . . .” Like, what am I gonna tell her? She’s gonna ask me all the questions that I tortured everybody else with . . .

LG: Now you’re getting your comeuppance.

NE: I’m so secular, but everybody teases me for having such a religious soul. They’re like, “You’re such a deeply religious person. Stop pretending,” but I’m like, “I’m not, you can’t make me be!” I think my wife is honestly afraid of coming in and finding me just tripling up on mezuzahs and koshering the kitchen . . .

LG: I want to ask about women and power in the novel.

NE: The moment I understood who Miri [Shuli’s wife] was, and about their household, was when I understood that it’s important to them that someone learn Torah full-time; she’s the smarter of the two and they agree that it should be her. The whole book changed for me understanding how they are as husband and wife. So much of his internal wrestling became conversations between them. He can’t live without her.

LG: Thinking about the Kaddish, as I was reading this novel: it’s a burden, it’s an absurd obligation, but it’s also an honor and an opportunity. What was the role of Kaddish in the book for you?

NE: My family and I, we are so different in our religiosity and our belief systems, but we really bridged that, and it made me think about the Kaddish. I try and be an ethical person, but the weight of Kaddish—it’s so gigantical. Someone has died and their soul in the world to come is literally gonna feel the hell fires, and you are their advocate on earth. The book’s scenario has to have had happened endlessly across time and space, where there is only this one male heir that can do it and he’s just not religious anymore. The family asks him to pray three times a day, for 11 months—it’s just too big for someone who’s like, “I’m not religious.” It’s not something you can do because you want to be nice. My father was a religious man and I thought about it—that there were things that needed to be done, and that he wanted to be done; the weight of that continuity across time and space is gigantic to me and seemed fitting for exploration.

LG: I feel that cities are often themselves characters in your work and that Jerusalem changes from book to book. The Jerusalem here is very different from the Jerusalem in your last novel. Are you sort of always writing about Jerusalem in some way?

NE: I love cities. I’m crazy about New York, and I’m crazy about Berlin, and I’m crazy about Jerusalem. Jerusalem holds such a giant place in my head. And yes, the last novel is the political Jerusalem, it’s the Jerusalem of conflict. It’s the Jerusalem of geo-politics. But the Jerusalem of this novel, it feels like a Jerusalem of the imagination. This one is outside of time. I thought a lot about the dreams in the book because I’m very sensitive about dreams in literature—you’re already making a dream into reality. But when you have a dream, especially in Jerusalem, that is a reality. Like seven years of famine—those dreams are for real. That could be a future reality.

LG: You really interrogate the idea of what home means in this novel. There is one line in the book where Shuli refers to Royal Hills, Brooklyn as “home-home” and it’s the only time he uses that phrasing. But given that he ends up—not to give too much away—in Jerusalem, it made me wonder, where are Jews at home?

NE: I think it’s hard to explain to people who don’t come from certain kinds of communities. Like if you asked me how much of the world is Jewish, I’d say, I don’t know, 98%? I was in Moscow for a book tour and it’s like, within three hours of crossing through customs, I’m eating glatt kosher Georgian food and drinking whiskey with a bunch of Hasidim—the same picture of the rebbe, like, everything familiar. If you’re an Orthodox Jew of a certain stripe, it doesn’t matter where I drop you in the world—there will be little, regional changes, but it’s gonna be basically the same.

Larry’s family is like, “Come home,” and I’m like, what does that mean? If your parents sell their house and they’re like, “Come home,” you’re like, “To where?” So I really was thinking about ideas of a Jewish home and what that means spiritually.

I teach in France for NYU, and when there is an attack or something horrible, Bibi will say, “Jerusalem is your home.” But the answer isn’t, “France is not your home,” the answer is, “Stop killing Jews.” You know what I mean? Who gets to decide their identity? What is the idea of real home? Is it [essentially] Jewish? That’s what Larry’s sister is claiming. She’s a Brooklyn woman living in Memphis and she’s saying, “This is your Jewish home,” and he’s like, “No. Subways. A place with subways is our home.” I guess it’s about the priorities you choose in life.

LG: This novel is really marked by the use of the internet, and I know you think a lot about God and the internet.

NE: I was theologically rebellious, which I believe on the rebellion chart, is the saddest, most pitiful kind. I wish I was just ripping monster bong hits from my compression bong, I would’ve had a much better time, but instead I was asking questions about God. One of the questions was about how we’re supposed to believe in a God that knows everything you’ve done, and where you are now, and what you’re gonna do next. Thirteen-year-old me found it hard to entertain the idea that God can hold what everyone is doing at once. But—wait a second—we’ve invented the internet, and now pretty much everyone who’s plugged in, you really can tell everything they’ve done, where they are now. Now my wife says “tortellini” and on my Instagram there’s an ad. Basically, we’ve built Beta God and that fascinates me. Like this thing that I thought was such an ask—so possible . . . I feel like the internet is much more Old Testament God because it’s really wrathful and unforgiving.

LG: The simulation of sex is a key part in this story.

NE: Part of the thing that obsesses me about the internet is that there are people behind it. Let’s say we walked outside and I fall on my face in a puddle and that goes viral. I know I’m a delicate flower or whatever, but it’s so horrifying to me that someone’s accidental, embarrassing something can be bigger than everything they could ever possibly do in their life. I look for pressurized form, so Larry’s simulated sex with a woman on the internet, and his being haunted by that, to me that’s better than the puddle—that’s a sharper, more vulnerable, more discussable form. Thinking of the woman behind a simulated sex act, that she is [real], that there is a person there, is a giant idea for me [as it relates to] the internet.

LG: As I was reading this, there seemed, whether intentional or not, winks to For the Relief of Unbearable Urges. The unbearable urges are in here too—the balance between strictures and being human. On one hand, Larry’s supposed to say Kaddish—like, this is in stone, you have to do it. But on the other hand, we’re only human, there has to be a work-around . . .

NE: You start to see your themes and for me, it’s always about this gray space in justice. The urges run through all the books, this idea of being human, physical beings. I’m tortured by that. But also this idea that there is some order, or some rule, or some idea of shame. I have left religiosity, but I still really believe in the rules. If there is a red light in the desert, even if I could see for 100 miles both ways and I knew it was broken, I would still die at the wheel. I’m writing a piece now thinking about how that religiosity feeds fiction, where religious devotion and creative devotion cross.

LG: How do you feel about the way your work is received in and outside of Jewish spaces?

NE: It’s taken me so long to start to organize my head on that. After my first book, I was really surprised when everyone was like: “The Jewish American” writer. I was like, what? Which is really dumb—of course, everything is Jewish in all of [my books]. It’s sort of flipped lately since we have open white supremacy as policy. Now I’m like, “Oh yeah, I’m a Jewish writer, double Jewish.”

But my defense of saying I’m not a Jewish writer, you know, if a story is functioning, it’s universal, that’s it. I get asked this question a lot: Can I give this to my gentile friend? I’m not Jewish, can I read this book? Nobody is asking, can I watch Game of Thrones, I don’t have a dragon. Even if you don’t have a dragon, you can probably follow along at home.

I love the community support

that I get, that means the world to me. Like, if you write a book about sailing

and it blows the sailors away . . . There’s something special when your world

works for a person who’s connected to that world, whatever it is. Still—and it

shouldn’t sound defensive because it’s not—it’s just supremely, intellectually

clear that stories function across time and space if they’re working. I’m happy

to be put in a box, but I don’t have to live in a box.

Lauren Goldenberg is deputy director at the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. She is a member of the Jewish Currents Board of Directors and of the Jewish Currents Council, and her book reviews and author interviews have appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books and Music & Literature.