What to Do When a Nazi Runs for President

A recent documentary revisits the 1986 election of a former Nazi to the Austrian presidency and the activists who sought to shut him down.

IF YOU’RE LOOKING for a visual shorthand for the disparities in how Germany and Austria have grappled with their roles in the Second World War, take a look at the architecture of their respective capital cities. Germany, whose cities were bombed heavily by the Allied forces, had to rebuild itself out of the literal and metaphorical ashes, to atone publicly for its crimes in order to repair its relationships with other nations. A hodgepodge of pre-war, modern, and contemporary buildings sit side-by-side on Berlin’s sprawling streets, jockeying for attention—the past literally carved into the city itself. There is no better symbol of this than the Reichstag building, constructed in the late 19th century, burned, bombed, left to ruin, and then subsequently restored, now crowned with an anachronistically modern but symbolically vital glass dome, to represent the transparency and openness of the new Germany.

Austria, however, is a different case altogether. Walk around the first district of Vienna, and you can pretend the war never happened. Genteel, centuries-old buildings dazzle with art nouveau flourishes, nestled between narrow cobblestone streets, while the sound of horse-drawn carriages echoes in your ears. Vienna’s historic districts present the ideal fin-de-siecle city, almost too perfectly picturesque, like a town in a snowglobe.

Ruth Beckermann’s The Waldheim Waltz, released in October in Austria and slowly arriving at select American theaters, tells the infuriating, disheartening, and ultimately far-too-prescient story of Kurt Waldheim’s ascension to the presidency of Austria in 1986, only forty-odd years after the end of the war—the inevitable result of Austria’s whitewashing of its own complicity in Nazi atrocities and what Beckermann calls “Austrian elasticity.” Waldheim, who was ultimately President of Austria from 1986-1992, was a well-regarded statesman and internationally-known figure: he had previously served as Austria’s foreign minister and was elected twice as Secretary-General of the United Nations. Yet as he began his run for president, his past as a decorated member of the Nazi occupying force in the Balkans—a past he had spent decades obfuscating and misrepresenting—began to emerge from the shadows of history.

Like a Viennese waltz, the pace of the The Waldheim Waltz is brisk and engaging. At its core is the incredible black and white footage Beckermann herself shot at the “Waldheim Nein” demonstrations, as the protests against Waldheim’s candidacy were called—an invaluable primary document. Beckermann, an acclaimed Austrian documentary filmmaker whose works often address questions of history, identity, and memory, urgently counts down the months leading up to the Austrian election. Beckermann supplements her protest videos with a variety of contemporaneous footage, giving a sense of the wide range of coverage the Waldheim Affair received as it was brewing. Dry, matter-of-fact news reports in English, French, and German are presented alongside interviews where Waldheim alternates between infuriating smugness and sneering faux-outrage. Passionate speeches denouncing Waldheim by members of the World Jewish Congress (the UN-affiliated group that most strongly protested Waldheim’s legitimacy as a world leader) are keenly juxtaposed with frothy news segments on the interior design of Waldheim’s New York apartment. Throughout, Beckermann’s serene, almost gentle voice-over narration invites the viewer to ponder the circumstances that allowed Waldheim to win the election, and whether a catastrophe of this nature can be averted in the future.

Bearing himself like a kindly grandfather, a family man, and a lover of his homeland, Waldheim perpetuated the fiction of his younger self as an innocent soldier who was injured on the front lines and who subsequently buried his head in law school texts. He was only doing his duty, he wasn’t in charge, both sides suffered. When he began to campaign for the presidency, Waldheim married his virtuous personal fiction to the comforting national fiction Austria wanted to hear: Austria as a downtrodden, victimized land that was mended and strengthened after the war through national unity and traditional values. It wasn’t until two months before the election in 1986 that the publication Profil published his military record card, proving that Waldheim had been a part of the Brownshirts and the Nazi Students League, and had taken part in the mass deportation of Greek Jews, that both fictions began to collapse.

The question in 1986 was: did Kurt Waldheim get this far because no one knew about his past, or because those who did know simply didn’t care? Indeed, watching the truth be revealed and then instantly disregarded by people who had already made up their minds provokes an unsettling sense of recognition in Trump’s America. The demonization of those fighting for justice—in the case of the “Waldheim Nein” movement, Jews, leftists, “elite” media, and “inciters” from inside Austria—is hardly unfamiliar. Also eerily familiar is the way that goalposts of decency seem to shift before one’s eyes: My enemies are lying, and even if I did do this thing, it’s not a big deal, everybody did it.

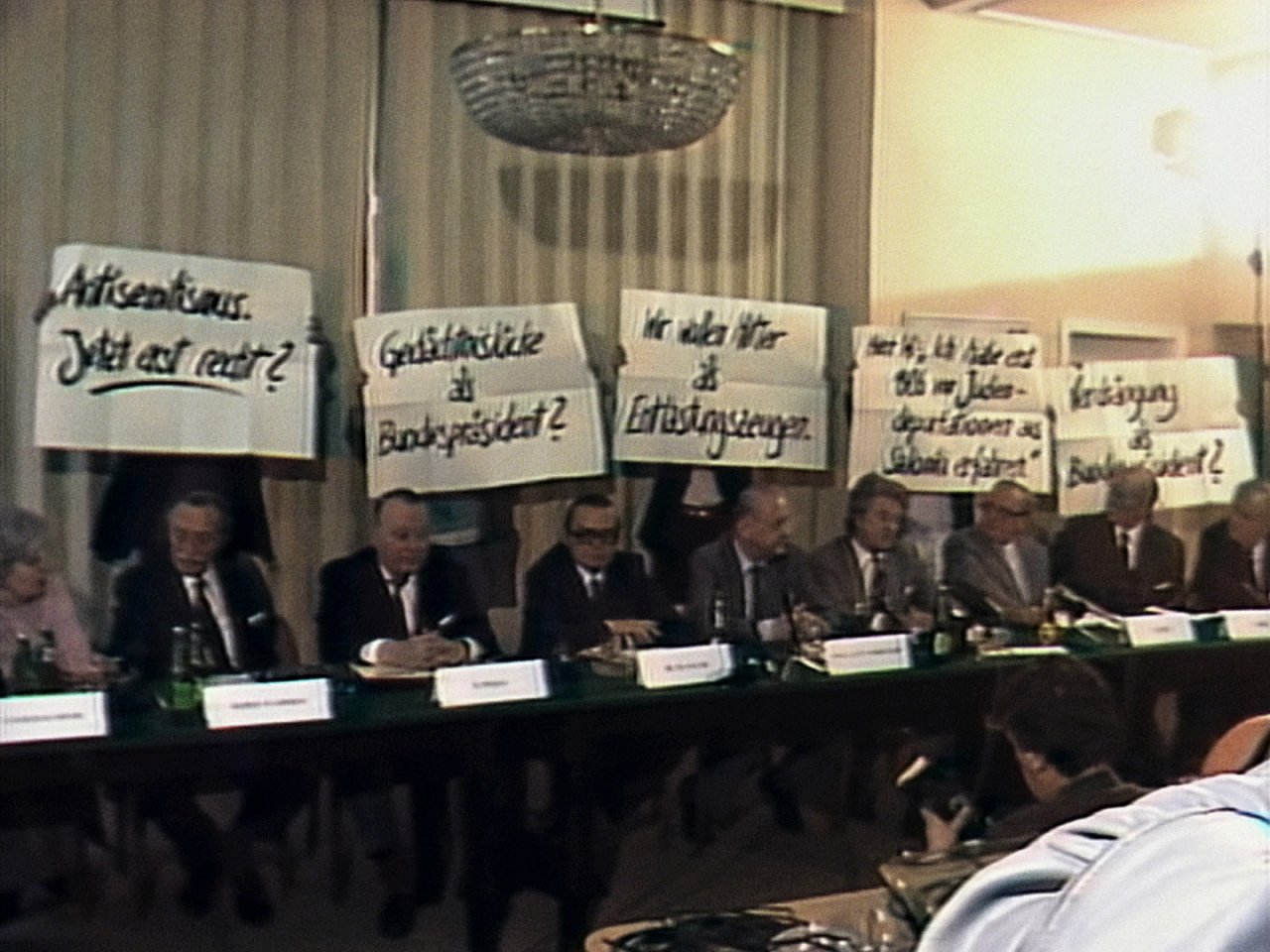

On a meta level, The Waldheim Waltz functions as a debate over the utility of direct action versus other forms of activism. Early in the film, Beckermann refers to herself as both a protester and a documentarian, but curiously, she withholds evidence of her own direct involvement in the “Waldheim Nein” movement until about a third of the way through the film, when the young activists meeting in Vienna’s Cafe Landtmann become “we.” She admits that she was one of seven protestors who disrupted a televised press conference in support of Waldheim in April 1986, silently holding up signs in front of their heads and shoulders, calling upon Hitler as a witness for the defense.

And yet Beckermann is decidedly ambivalent about her work as both activist and documentarian. “Either you document or you protest, you have to choose,” she declares in voice-over while the press conference protest footage rolls, ironically undercutting her own argument. Does one have to choose between being the participant or the observer, between being message or messenger? In the age of live-streaming as a tool for activism, when Netflix boasts pages and pages of documentaries with a justice agenda, it seems as though this distinction is not as fraught; to modern-day eyes, Beckermann herself seems to have accomplished both. The Waldheim Waltz functions as both an invaluable look at a protest movement fighting against a right-wing political insurgency, and also a call to action, creating a sense of righteous fury and a desire to prevent another Waldheim from ever taking power again.

With the benefit of hindsight, the entire “Waldheim Affair” is a slow-motion trainwreck. As the June 20, 1986 New Yorker “Letter From Europe” notes, there were seemingly infinite possibilities for Waldheim to have been properly vetted two decades before his presidential run.

And as Beckermann clearly lays out, there were red flags as to the true character of Kurt Waldheim, if only people had bothered to pay attention, such as his reluctance to discuss his life during the war years and his deliberate obfuscation and elision when confronted, or his pointed refusal to cover his head during the recitation of the Mourner’s Kaddish in Jerusalem while representing the UN.

The excuses for people like Waldheim are myriad: they were victims—the first victims, in fact; they were drafted into the SS without a choice; they didn’t know what was happening to the Jews, to the Roma, to the disabled and others deemed unworthy of life. As Beckermann points out, both left-wing and right-wing government officials in Austria fought for the release of SS war criminal Walter Reder from prison in Italy, showing across-the-board complicity in this purposeful forgetting. There was no public period of reckoning in Austria, no lingering sense of responsibility for their role in the Holocaust. And so the Austrian collaborators escaped into their beautiful, pristine cities and countrysides, slipped into the shadows, into respectability, into politics, back into power. The Waldheim Waltz shows in precise, devastating detail just what can—and will—happen if countries cannot confront and acknowledge painful historical truths, providing a grim lesson for every nation that’s fallen prey to fascism and bigotry.

Deborah Krieger is an arts writer and curatorial assistant based in Philadelphia. She has written for BUST, PopMatters, the Forward, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and the Mary Sue.