Translating Black Lives Matter into Yiddish

Amid an eruption of protests over police brutality, a Black performer of Yiddish music reflects on an attempt to “touch Blackness from inside Yiddish.”

ON THE EVENING OF MAY 31st—a week after George Floyd was murdered by a police officer and amid an eruption of protests nationwide—I was tagged in a query on Twitter asking how to translate the phrase “Black Lives Matter” into Yiddish. Working for the past eight years primarily as a performer and composer of Yiddish kunstlider (art song), I am frequently asked to make spontaneous translations into the language in which I work, in spite of my decidedly intermediate level of fluency.

Being a Black performer of Yiddish has also made me a locus of assertions about the language and its relationship to otherness: Yiddish is for many a symbol of “authentic Jewishness” and/or internationalist values, and as such, my engagement with it as a Black man has occasionally been held up as an example of inherent Jewish exceptionalism and liberality. And yet, Yiddish remains a language largely assumed to be a matter of Black incomprehension—a language that has spoken about Blackness from the outside.

Reading over the suggested translations of “Black Lives Matter” in replies to the initial Twitter query, I realized I was watching a discussion attempting to touch Blackness from inside Yiddish. Right away, well-meaning attempts at translation featuring the word “shvartse” gave me pause. Though it has historical and literary precedent in the Yiddish language for the respectable discussion of Black people, it also has a parallel history of pejorative use as a racial slur in American Yiddish. This complexity was well-known to me. It has been complicated for me to speak about myself and my music in Yiddish. At the beginning of my career, I amateurishly used the word “shvartser” to refer to myself, while more recently, I have described a project of mine, which combines a hundred years of African American and Ashkenazi Jewish music, as “Afroamerikanishe-Yidishe muzik.”

With the full context of the word “shvartse” in mind, I responded in the Twitter thread that the ikker (essence) of an expression of self-determination, especially when it becomes the name of a movement, is best expressed in the sounds and language of its origin—in other words, “Black Lives Matter” in Yiddish should be “Black Lives Matter.” This was not exactly an evasion. I thought of the phrase “¡No pasarán!”—associated with political resistance to the dictator Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War, and which has come to signify resistance to fascism broadly in the decades since—and how the power and importance of the phrase lies in its remaining untranslated and thus rooted in the historical moment in which it came into being.

The next morning, while reading a Facebook post by a Yiddishist (in English) about a peaceful memorial protest in Boston that the police had violently dispersed with clouds of tear gas, my thoughts returned to the relationship between the current moment and the Yiddish language. There was a clarity to my colleague’s recollection; the short, descriptive sentences reminded me of the kind of first-person reportage of historical events that would have been found in Yiddish-language American publications like The Forverts and Morgen Freiheit.

As I idly wondered how the past week of protest would be described in the Yiddish press of yesteryear—or today, for that matter—I received an email with the subject line “#BLM oyf yiddish.” Yiddish translator and anti-racism educator Jonah Boyarin had included me in a group of Yiddishists on a Google Doc where terms were being drafted for the general discussion in Yiddish of the Black Lives Matter movement: a collection of phrases covering the name of the movement itself; the systemic forces and practices it opposes (white supremacy, prejudicial treatment, racial profiling); and its aims (racial and economic justice, intersectional movement building). It also featured vocabulary for describing Jews of color and allies, and terms particular to the experience of protest (police brutality, curfew, “the crowd chanted ‘fuck the police’”) in the wake of the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black people at the hands of the police and a white supremacist system.

That night, I hashed out some of my thoughts about the translations on the phone with Jonah. My previous considerations about the attempts to translate “Black Lives Matter” into Yiddish informed the group’s final decision to directly transliterate the English phrase into yidishe oysyes (Hebrew letters). A direct transliteration of English into normative Yiddish sounds renders “black lives matter” into “blek lives metter,” which is, to our thinking, a close enough approximation:

בלעק לײַװס מעטער

The group also decided that the transliteration of “Black Lives Matter” should be immediately followed by a parenthetical with a direct translation of the phrase into Yiddish using the descriptor “African American” instead of “Black.” A number of interpretations were produced:

אַפֿראָאַמעריקאַנער לעבנס האָבן אַ װערט

Afroamerikaner Lebns Hobn a Vert

אַפֿראָאַמעריקאַנער לעבנס זענען וויכטיק

Afroamerikaner Lebns Zenen Vikhtik

אַפֿראָאַמעריקאַנער בלוט איז נישט קײן װאַסער

Afroamerikaner Blut iz Nisht Keyn Vaser

The first two interpretations, to our thinking, were very close to the original sentiment. The last one—literally “African American Blood is Not Water”—interpreted the essence of the phrase through the adaptation of a pre-existing Yiddish version of the idiom “Blood is thicker than water” (literally: “Blood is not water”).

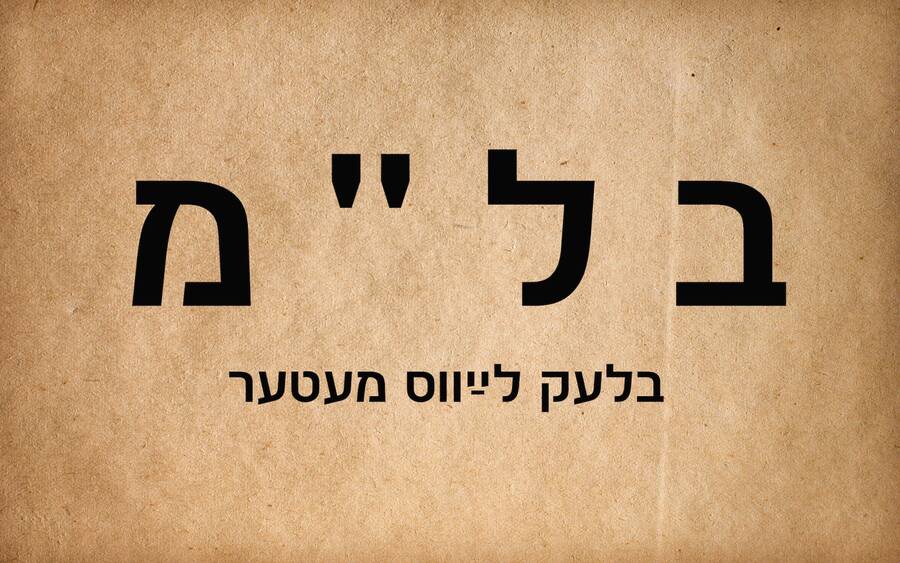

For the purposes of expediency in a journalistic or literary context, the full phrase and its parenthetical would be used only for its initial mention, and the acronym בל״מ would be used thereafter. The last mem, which stands for “matter,” is not a final mem, according to Yiddish practice for acronyms.

The choices behind the construction of a phrase like “Black Lives Matter” in Yiddish are deliberate and imperfect. To some degree, the imperfection is the point; developing a new vocabulary is a constantly unfolding process. I fully anticipate criticism of the phrase as unwieldy, needlessly “politically correct” and “inauthentic.” I have already seen one heritage speaker of Yiddish critique the decision to “Yiddishize” the words “Black” and “African American,” writing that Yiddish already has an established word for black: “shvartse.” They say that the word is not pejorative, any more than using the word to describe an object that is black is pejorative. Others have said that the issues with the word are in fact issues with American racism, and not with Yiddish itself (as though the two can be cleanly separated, or racism has only existed among American speakers of the language); they insist that these American circumstances should not inform how they speak their Yiddish.

As a Black Yiddish speaker, this strikes me as disingenuous at best and heartless at worst: Why value the expediency of a word over the possibility of denigrating another human being? And yet I can acknowledge the fact that for certain full-time Yiddish speakers (as opposed to a performer like myself), the utility of a phrase like “Black Lives Matter” in Yiddish is negligible. Though it uses words in their language, it addresses concerns decidedly outside their experience, exterior to their lives, their communities, their Yiddish. This phrase in Yiddish, like me, comes from the outside, as much as the word “shvartse” has come from the inside.

Over the past couple of days I’ve had to consider who a phrase like “Afroamerikaner Lebns Zenen Vikhtik” is for. Perhaps it’s for people who want to express their solidarity with the sanctity of Black life in a language they have reclaimed, or perhaps have always spoken. Perhaps it is for Ashkenazi Jews who have begun to do the work of eroding the effects of American racism—or for those who have persisted in doing the work—and would like to see it as continuous with the work of previous, Yiddish-speaking generations.

Curiously, as I write this, I realize that among all of these worthy people, this phrase is for me, for someone who has previously avoided making any bold self-assertions in his adopted language of parnose (livelihood) and artistic self-expression. I’ve done so much living through the Yiddish language, and now I have words to declare that this living—this life—matters.

Anthony Russell is a performer of music in Yiddish with contributions in The Forward, Tablet, JTA, PROTOCOLS and, recently, Jewish Currents and In Geveb.