The Right to a History Without Lies

With the ruling that two prominent Holocaust scholars must apologize for defaming the “good name” of the Polish nation, the chilling of speech enters a sinister new phase in Poland.

THE VERDICT WAS DELIVERED via video link from the Warsaw District Court on February 9th, but its grave effects were already unfurling well before the reading of the judgement. Quietly, for the past several years, graduate students, academics, and teachers across Poland have been adjusting their dissertation subjects, qualifying their research findings, obscuring their prose. They do not want to be accused of defaming the good name of the Polish nation by suggesting that some Poles, in some places, contributed to the Shoah. To do so would be to make themselves vulnerable to both civil and criminal litigation, to risk lofty fines and imprisonment. They’ve seen what has happened to the two renowned historians on trial, who have been called liars and propagandists by the press and by elected politicians. They do not want to be next.

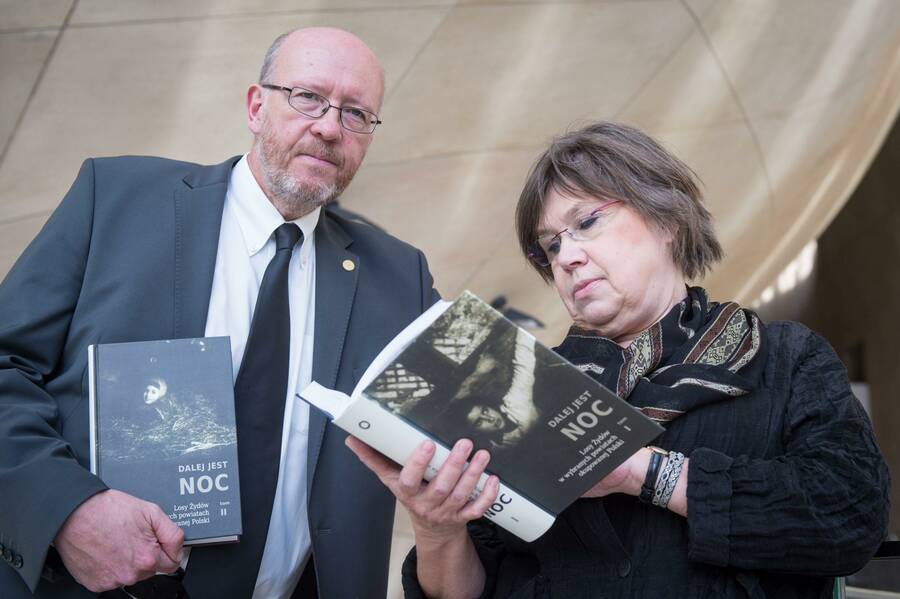

The defendants—Barbara Engelking, founder and director of the Polish Center for Holocaust Research, and her colleague Jan Grabowski, a professor of history at the University of Ottawa—stood accused of violating the personal rights of a dead man and his descendants. Their alleged violation occurred in a four-sentence passage in their monumental 1,640-page historical study on the fate of Jews in occupied Poland, Night Without End. In the passage, Engelking summarizes the testimony of a Holocaust survivor named Estera Drogicka, who relates that Edward Malinowski, the wartime mayor of a village where she took shelter, betrayed over a dozen Jews to the Germans during the war. For recounting this statement, the Polish League Against Defamation (RDI)—a right-wing NGO whose name is modeled on that of the American Anti-Defamation League, though there is no connection between the two organizations—sued the historians, demanding 100,000 zlotys (about $27,000) and a written apology. The prosecuting attorney called it a “simple civil case,” just a run-of-the-mill defamation suit. The defense attorneys saw the case differently: as a textbook example of what is known in legal parlance as a SLAPP suit—a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation, used all over the world to dissuade the exercise of free speech by threat of heavy legal fines and protracted proceedings.

The lawsuit was filed in the name of Malinowski’s niece, an 81-year-old woman named Filomena Leszczynska, though it is RDI that prepared the case, hired a law firm, developed a public relations campaign, and is covering Leszczynska’s legal fees. At a virtual press conference released nine days after the verdict, one of Leszczynska’s lawyers, Monika Brzozowska–Pasieka, emphasized that the defendants had not only “infringed upon” her client’s “good name” and “personal rights,” but also upon her “national identity.” The suggestion that to defame an individual is also to defame a nation, and vice versa, lies at the heart of the case. “A new category of personal rights is now emerging in Poland, encompassing the ‘right to national pride,’ the ‘right to national identity’ and the ‘right to true history’’’—in Polish, the “right to a history without lies”—as Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias, a member of the defense team for Grabowski and Engelking, explained in a recent interview. This is a history in which neither the Polish state nor any of its citizens are implicated in the Holocaust that was perpetrated in their occupied nation. Rather, Poles are innocent victims, as former Prime Minister Beata Szydlo has asserted, or heroes who rescued their Jewish neighbors. “This is not about historical truth,” Gliszczyńska-Grabias said to Jewish Currents. “It’s about winning a competition of victimhood and memory.”

This fight for the nation’s “good name” accelerated after the far-right ruling coalition, led by the Law and Justice party, came to power in 2015. It set about weaponizing the judicial system in support of a nationalist narrative, passing multiple laws that litigated the way the past could be retold and supporting NGOs that promoted a story of Polish irreproachability. In 2018, the government passed two amendments to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance, which rendered the mere suggestion that Poland, or any Polish person, was responsible for or complicit in the Holocaust a criminal offense. (An initial version of the amendment came with a penalty of up to three years in prison, which was later removed after international outcry.) These acts buttressed the nationalist agenda by establishing that, from the Polish government’s point of view, Germany bears sole responsibility for the Holocaust. “The government promised Poles a wonderful, better future, and was more and more unable to deliver on that,” said journalist and Jewish intellectual Konstanty Gebert. “So it started paying more attention to delivering a better past.”

The guilty verdict in the historians’ case has marked a sinister new phase in the right-wing government’s protracted effort to deliver this right to a “history without lies”—one that holds the potential to conscript every individual Pole into the effort to litigate what can be said about their country. It is notable that Engelking and Grabowski were tried in civil court, sued by a private citizen instead of directly by the Polish state. There was already some precedent for this use of the civil system: In 2019, Maciej Świrski, the head of RDI, sued a German daily newspaper, the Frankfurter Rundschau, for criticizing the Polish government’s approach to history, claiming that the newspaper’s assertions constituted a personal attack on his “national identity, heritage and good name as a Pole.” The Warsaw District Court ruled in his favor, ordering the newspaper to post an apology on its website for one week. (Though the newspaper is not based in Poland, the European Court of Justice advised that the Polish District Court still had jurisdiction to try a suit of this kind; Frankfurter Rundschau published the apology.) Now, the expanded use of civil proceedings may signal the advent of a legal environment in which, as Engelking writes in an article on the suit, “anyone who feels Polish might sue anyone who expresses a critical opinion about the Polish Nation, and perhaps even the Polish State.”

ESTERA DROGICKA WEARS a purple floral print dress with lace trim, pearl earrings, and a bandage on her right hand. It is July 1996, a half-century after the war, and she is being filmed giving her testimony. She long ago abandoned her old surname, having settled in Sweden and married a man with the surname “Wiltgren.” She leans toward the interviewer, who sits off camera, posing questions about her experiences during the Holocaust, for an account of how she survived. The crest of the University of Southern California, whose Shoah Foundation maintains one of the largest collections of survivor testimony in the world, hovers, immobile, beside Drogicka’s expressive face. It is in this testimony that Drogicka makes the claim at the center of the contemporary court case, stating that Malinowksi betrayed a group of Jewish people hiding in a forest.

The historians’ case turns on the fact that, in 1949, Drogicka delivered contradictory testimony in a Polish court. Malinowski was being tried for collaborating with the Germans and betraying the locations of 18 Jewish people. Many witnesses in the case were beaten and threatened in advance of the proceedings; most of the witnesses for the prosecution did not appear in court. Drogicka appeared as a witness for the defense, and she praised Malinowski for helping her pass as a non-Jewish woman and secure work in Germany. “For a good few weeks I hid in Malinowski’s barn and he fed me, even though I was penniless,” she said then. “At night his barn was full of Jews. Malinowski gave them food . . . I owe Malinowski my life.”

In the Warsaw District Court, it was left to the judge, Ewa Jończyk, to read the two testimonies and determine which version to trust. Her assessment of the historians’ guilt or innocence would turn on her conclusions about the veracity of the statement they had summarized. Given that both Drogicka, the witness, and Malinowski, the perpetrator, were dead, the lawyers found themselves with little more than documents and tapes to cross-examine, and only descendants to question and depose. Drogicka’s two sons, summoned to testify for the defense, flew in from Sweden and Australia to tell the court that their mother’s USC testimony accorded with their private family conversations. The prosecution, for its part, requested that a body language and speech expert be summoned to analyze the tapes of Drogicka’s testimony, which they expected would further discredit her account. (The court refused this request.)

Just as the plaintiff was being used as a vehicle for the government’s nationalist argument, the historians were forced to defend Drogicka’s testimony as a proxy for the reliability of their own work, and of survivors’ stories in general. Gliszczyńska-Grabias argued that the conditions in which the second testimony was taken—decades after the events in question, in an extrajudicial setting—were far better than those of the first in-court testimony from 1949. “[The USC testimony] was given in a safe environment, many years after the war, during a long, long conversation on many aspects of her life,” she said. She pointed to the precarious circumstances of the 1949 testimony. “We need to remember, this was a world in ruins, and so was the court system of that time,” she explained. “For Jewish survivors in Poland after the war, it was desperate. In order to make a living here, as a Jew, you had to behave in a particular way.” Complicating the question of whether the historians had done their due diligence was the fact that their manuscript contained a small error, reporting that Drogicka traded household items with the mayor Edward Malinowksi, when in fact she had traded with a different man by the same name. The historians said the error would be corrected in a subsequent edition, and was irrelevant to the accusations of complicity in murder.

To some observers, the verdict, when it came, exemplified the diminishing options available to a judiciary engaged in a Sisyphean battle to protect what remains of its integrity. The judge did not hand the government a complete victory, denying the plaintiff’s request for a heavy fine, which she argued would have an unacceptable chilling effect on scholarly research. But, by requiring that the historians issue an apology, neither did she deny the government a ruling in its favor. In this regard, the verdict seems to be a grave indicator of the extent and relative ease with which the nation’s entire body of laws—not just criminal code, but also the civil one—has been co-opted to serve revisionist ends. Engelking and Grabowski’s lawyers will soon begin preparing their appeal, but the appeal will be heard in a court whose judges serve at the behest of the minister of justice, Zbigniew Ziobro, who has already endorsed the first verdict. Both the defense and prosecution expect the case to end up in Strasbourg, at the European Court of Human Rights.

The ruling ignited an international scandal, with swift statements of condemnation from Yad Vashem, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the American Historical Association, the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure, and from Holocaust researchers around the world. These statements called the ruling a threat to academic freedom, an attempt to discourage scholarly inquiry. They cautioned that the question of the dead man’s culpability was something for historians, not lawyers, to answer. “We call upon the government of Poland to protect researchers against politically motivated interference in the pursuit of independent scholarship rooted in archival evidence,” the New York-based Center of Jewish History said in a statement.

But the condemnations from abroad were countered by notable statements of support in Poland itself. A recent poll commissioned by a Polish news outlet found that 39% of respondents agreed that “historians who jeopardized Poland’s reputation” should be “brought to justice.” Meanwhile, the Polish minister of justice took to social media to celebrate the ruling, cheering the fact that a “brave woman” had “stood up to deceptive propaganda slandering Poles!” One of his deputies applauded the plaintiff, who he wrote had successfully “defended the good name of her uncle who saved Jews from German criminals.” According to Gebert, the verdict, and its support in the justice ministry, sends a clear message about “what you’re not supposed to write about if you know what’s good for you”—a warning intended especially for the local reporter and other ordinary couriers of public opinion who, unlike the historians, lack the influence to inspire a wave of international support.

Meanwhile, right-wing NGOs are on the lookout for other cases. Ordo Iuris, an ultra-Catholic NGO, recently announced that it will sue the public radio station France Culture for defaming the Polish nation in a segment on the Holocaust. Another case may be taking shape against the journalist and scholar Katarzyna Markusz. In October, she wrote an article in which she asked whether she would “live to see the day” when Polish authorities, like their German counterparts, would “admit that the dislike of Jews was widespread among Poles, and that Polish complicity in the Holocaust is a fact of history.” While she does not know who alerted the authorities to her article, she suspects it was yet another right-wing NGO. In early February, Markusz spent an hour in police questioning. “They asked, ‘Did I mean to offend the Polish nation? I said, ‘No, of course not.’ This is something that can be read in historical books, testimonies, articles,” she said. “You cannot be offended by the truth.” (Markusz found out weeks later, from another journalist, that the case against her had been dropped. But she worries that there are more to come.)

Outside the court system, a broader chilling effect is already well underway. “I know people who have changed their master’s theses in order not to get in trouble,” Gebert said. Irena Grudzinska Gross, a research scholar of Eastern European history and culture at Princeton whose former husband, the historian Jan T. Gross, was questioned by Polish authorities over his work on the Holocaust in 2015, is currently editing a scholarly collection on Jewish–Polish relations during and after the war. One of her authors, she said, submitted changes to the manuscript after a descendant of a research subject threatened the author with a lawsuit. “It’s a way of silencing people,” said Grudzinska Gross. “This is why it is so dangerous: If you cannot name the people who participated, name the places, or look at concrete events because you are afraid the third generation of family descendants will sue you, then you cannot do your work.” To avoid the threat of lawsuits completely, historians would have to depict the Shoah as an abstract event perpetrated by nameless individuals in diffuse locations, not as a specific catastrophe visited upon specific bodies in specific places. “The government already won, even if it ultimately loses the case,” said Elzbieta Janicka, a cultural scientist specializing in Polish antisemitism at the Polish Academy of Sciences.

With every calamity, there is a moment when law gives way to history, when prosecutorial questions become scholarly ones, and the pursuit of legal redress is replaced by the mandate for lasting moral judgement. The Polish government, like other revanchist governments past and present, has discovered that this is a reversible transfer of power. “The law becomes a weapon in the hands of the authoritarian state as opposed to a shield of the people from the state,” said Jonathan Brent, executive director of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. In Warsaw and elsewhere in Eastern Europe, courts have taken hold of history once more. Nationalist regimes like Poland’s “use liberal methods, and especially law, for illiberal purposes,” Grudzinska Gross said. “Nothing has been established in a way that cannot be erased.”

Linda Kinstler is a PhD candidate in rhetoric at UC Berkeley and a Jewish Currents contributing writer. Her writing has appeared in The Guardian Long Read, The New York Times Magazine, 1843 Magazine, and more. She is the author of Come to this Court and Cry.