The Men With the Pink Triangle

An excerpt of one of the first complete testimonies from a Holocaust survivor sent to a concentration camp for homosexuality.

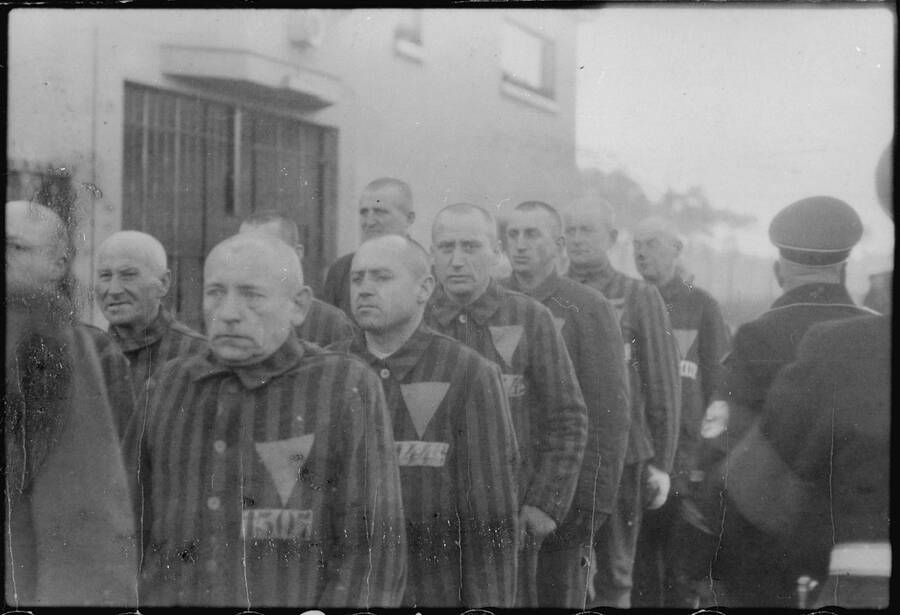

Prisoners in the concentration camp at Sachsenhausen, Germany, on December 12th, 1938.

When The Men With the Pink Triangle was originally published in 1972, it was among the first full testimonies from a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps imprisoned for being gay. Historians estimate that up to 15,000 men accused of homosexuality were sent to the camps during the Reich. But as writer and activist Sarah Schulman explains in her preface to a new edition of the book, West Germany lagged in legally acknowledging them as victims of the Nazi regime. When this account of Josef Kohout’s arrest, deportation, and survival was released, sections of Paragraph 175—the anti-sodomy law the Nazis used to prosecute people accused of “engaging in homosexual activity”—were still part of the country’s penal code; in fact, some who had survived the camps were retried and convicted under the same morality law in the 1950s and ’60s. The mass-market publication of Kohout’s anonymous testimony—as told to the writer Heinz Heger (the pen name of Hans Neumann)—marked a watershed moment in postwar Holocaust memory, as “homosexual victims” of the Nazi regime first entered public view and the struggle for gay liberation in Germany began to take flight.

The Men With the Pink Triangle first appeared in English in 1980, translated by David Fernbach, and was reissued by Haymarket Books this year. The following excerpt is the complete first chapter of this painful account.

Vienna, March 1939. I was twenty-two years old, a university student preparing for an academic career, a choice that met my parents’ wishes as much as my own. Being little interested in politics, I was not a member of the Nazi student association or any of the party’s other organizations.

It wasn’t as if I had anything special against the new Germany. German was and still is my mother tongue, after all. Yet my upbringing had always been more Austrian in character. I had learned a certain tolerance from my parents, and at home we made no distinction between people for speaking a different language from ours, practicing a different religion, or having a different color of skin. We also respected other people’s opinions, no matter how strange they might seem.

I found it far too arrogant, then, when so much started to be said at university about the German master race, our nation chosen by destiny to lead and rule all Europe. For this reason alone, I was already not particularly keen on the new Nazi masters of Austria and their ideas.

My family was well-to-do and strictly Catholic. My father was a senior civil servant, pedantic and correct in all his actions, and always a respected model for me and my three younger sisters. He would admonish us calmly and sensibly if we made too much of a row, and he always spoke of my mother as the lady of the house. He had a deep respect for her, and as far as I can recall, he never let her birthday or saint’s day pass without bringing her flowers.

My mother, who is still alive today, has always been the very embodiment of kindness and care for us children, ever ready to help when one of us was in trouble. She could certainly scold if need be, but she was never angry with us for long, and never resentful. She was not only mother to us, but always a good friend as well, whom we could trust with all our secrets and who always had an answer even in the most desperate situation.

Ever since I was sixteen I knew that I was more attracted to my own sex than I was to girls. At first I didn’t think this was anything special, but when my school friends began to get romantically involved with girls, while I was still stuck on another boy, I had to give some thought to what this meant.

I was always happy enough in the company of girls, and enjoyed being around them. But I came to realize early on that I valued them more as fellow students, with the same problems and concerns at school, rather than lusting after them like the other boys. The fact that I was homosexual never led me to feel the slightest repulsion for women or girls—quite the opposite. It was simply that I couldn’t get involved in a love affair with them; that was foreign to my very nature, even though I tried it a few times.

For three years I managed to keep my homoerotic feelings secret even from my mother, though I found it hard not to be able to speak about this to anyone. In the end, however, I confided in her and told her everything that was necessary to get it off my chest—not so much to ask her advice, however, as simply to end this burden of secrecy.

“My dear child,” she replied, “it’s your life, and you must live it. No one can slip out of one skin and into another; you have to make the best of what you are. If you think you can find happiness only with another man, that doesn’t make you in any way inferior. Just be careful to avoid bad company, and guard against blackmail, as this is a possible danger. Try to find a lasting friendship, as this will protect you from many perils. I’ve suspected it for a long time, anyway. You have no need at all to despair. Follow my advice, and remember, whatever happens, you are my son and can always come to me with your problems.”

I was very much heartened by my mother’s reasonable words. Not that I really expected anything else, as she always remained her children’s best friend.

At university I got to know several students with views, or, rather, feelings, similar to my own. We formed an informal group, small at first, though after the German invasion and the “Anschluss” this was soon enlarged by students from the Reich. Naturally enough, we didn’t just help one another with our work. Couples soon formed too, and at the end of 1938 I met the great love of my life.

Fred was the son of a high Nazi official from the Reich, two years older than I, and set on completing his study of medicine at the world-famous Vienna medical school. He was forceful, but at the same time sensitive, and his masculine appearance, success in sport, and great knowledge made such an impression on me that I fell for him straightaway. I must have pleased him too, I suppose, with my Viennese charm and temperament. I also had an athletic figure, which he liked. We were very happy together, and made all kinds of plans for the future, believing we would nevermore be separated.

It was on a Friday, about 1 p.m., almost a year to the day since Austria had become simply the “Ostmark,” that I heard two rings at the door. Short, but somehow commanding. When I opened I was surprised to see a man with a slouch hat and leather coat. With the curt word “Gestapo,” he handed me a card with the printed summons to appear for questioning at 2 p.m. at the Gestapo headquarters in the Hotel Metropol.

My mother and I were very upset, but I could only think it had to do with something at the university, possibly a political investigation into a student who had fallen foul of the Nazi student association.

“It can’t be anything serious,” I told my mother, “otherwise the Gestapo would have taken me off right away.”

My mother was still not satisfied, and showed great concern. I, too, had a nervous feeling in my stomach, but then doesn’t anyone in a time of dictatorship if they are called in by the secret police?

I had a nervous feeling in my stomach, but then doesn’t anyone in a time of dictatorship if they are called in by the secret police?

I happened to glance out of the window and saw the Gestapo man a few doors farther along, standing in front of a shop. It seemed he still had his eye on our door, rather than on the items on display.

Presumably his job was to prevent any attempt by me to escape. He was undoubtedly going to follow me to the hotel. This was extremely unpleasant to contemplate, and I could already feel the threatening danger.

My mother must have felt the same, for when I said goodbye to her she embraced me very warmly and repeated: “Be careful, child, be careful!”

Neither of us thought, however, that we would not meet again for six years, myself a human wreck, she a broken woman, tormented as to the fate of her son, and having had to face the contempt of neighbors and fellow citizens ever since it was known her son was homosexual and had been sent to a concentration camp.

I never saw my father again. It was only after my liberation in 1945 that I learned from my mother how he had tried time and again to secure my release, applying to the interior ministry, the Vienna Gauleitung, and the Central Security Department in Berlin. Despite his many connections as a high civil servant, he was continually refused.

Because of these requests, but above all because his son was imprisoned for homosexuality, and this was incompatible with his official position under the Nazi regime, he was forced to retire on reduced pension in December 1940. He could no longer put up with the abuse he received, and in 1942 took his own life—filled with bitterness and grief for an age he could not fit into, filled with disappointment over all those friends who either couldn’t or wouldn’t help him. He wrote a farewell letter to my mother, asking her forgiveness for having to leave her alone. My mother still has the letter today, and the last lines read: “and so I can no longer tolerate the scorn of my acquaintances and colleagues, and of our neighbors. It’s just too much for me! Please forgive me again. God protect our son!”

At five to two I reached the Gestapo HQ. It was a hive of activity, SS men coming and going, men in Nazi uniforms or with the gold party badge hurrying through the corridors and up the stairs. Some men in civilian clothes passed me just as I came through the front door. You could see from their faces that they were very glad to have gotten out of the building.

I showed my summons, and an SS man took me to department IIs. We stopped outside a room with a large sign indicating the official within, until a secretary sitting in the antechamber, also in SS uniform, showed us in. “Your appointment, Herr Doktor!” The SS man handed in my card, clicked his heels, and vanished.

The “doctor,” in civilian clothes, but with the short, angular haircut and smooth-shaven face that immediately gave him away as a senior officer, sat behind an imposing desk piled up with files, all neatly arranged. He neither greeted me nor even looked at me, but just carried on writing.

I stood and waited. Still nothing happened, for several minutes. The room was quite silent and I scarcely dared breathe, while he steadily wrote on. The only sound was the scratch of his pen. I became more and more nervous, though I recognized the “softening-up” tactic. Quite suddenly he laid down his pen and stared at me with cold gray eyes: “You are a queer, a homosexual, do you admit it?”

“No, no, it’s not true,” I stammered, almost stunned by his accusation, which was the last thing I expected. I had only thought of some political affair, perhaps to do with the university; now I suddenly found my well-kept secret was out.

“Don’t you lie, you dirty queer!” he shouted angrily. “I have clear proof, look at this.”

He took a postcard-sized photo from his drawer. “Do you know him?”

His long hairy finger pointed at the picture. Of course I knew the photo. It was a snap someone had taken showing Fred and me with our arms in friendly fashion around each other’s shoulders.

“Yes, that’s my student friend Fred X.”

“Indeed,” he said calmly, yet unexpectedly quick: “You’ve done filthy things together, don’t you admit?” His voice was contemptuous, cold, and cutting.

I just shook my head. I couldn’t get a word out; it was as if a cord were tied round my neck. A whole world came tumbling down inside me, the world of friendship and love for Fred. Our plans for the future, to stay faithful together, and never to reveal our friendship to outsiders, all this seemed betrayed. I was trembling with agitation, not only because of the “doctor’s” examination, but also because our friendship was now revealed. The “doctor” took the picture and turned it over. On it read: “To my friend Fred in eternal love and deepest affection!” I knew as soon as he showed me the photo that it had my vow of love on the other side. I had given it to Fred for Christmas 1938. It must have got into the wrong hands, I immediately thought. Perhaps his father had found it, though that seemed quite improbable, as he didn’t bother much about his son, or at least that was how it seemed. But now the photo was here on the table, before me and the Gestapo man.

“Is that your writing and your signature?” I nodded, tears rising to my eyes.

“That’s all, then,” he said jovially, content. “Sign here.”

He handed me a sheet half written on, which I signed with trembling hand. The letters swam in front of my eyes, my tears now flowing openly. The SS man who had brought me here was now back in the room again.

“Take him away,” said the “doctor,” giving the SS man a slip of paper and bending over his files again, not deeming me worthy of further attention.

I was taken the same day to the police prison on Rossauerlände street, which we Viennese know as the “Liesl,” as the street used to be called the Elisabethpromenade.

My pressing request to telephone my mother to tell her where I’d been taken was met with the words: “She’ll soon know you’re not coming home again.”

I was then examined bodily, which was very distressing, as I had to undress completely so that the policeman could make sure I was not hiding any forbidden object, even having to bend over. Then I could get dressed again, though my belt and shoelaces were taken away. I was locked in a cell designed for one person, though it already had two other occupants. My fellow prisoners were criminals, one under investigation for housebreaking, the other for swindling widows on the lookout for a new husband. They immediately wanted to know what I was in for, which I refused to tell them. I simply said that I didn’t know myself. From what they told me, they were both married, and between thirty and thirty-five years old.

When they found out that I was “queer,” as one of the policemen gleefully told them, they immediately made open advances to me, which I angrily rejected. First, I was in no mood for amorous adventures, and in any case, as I told them in no uncertain terms, I wasn’t the kind of person who gave himself to anyone.

They then started to insult me and “the whole brood of queers,” who ought to be exterminated. It was an unheard-of insult that the authorities should have put a subhuman such as this in the same cell as two relatively decent people. Even if they had come into conflict with the law, they were at least normal men and not moral degenerates. They were on a quite different level from homos, who should be classed as animals. They went on with such insults for quite a while, stressing all the time how they were decent men in comparison with the filthy queers. You’d have thought from their language that it was me who had propositioned them, not the other way round.

As it happened, I found out the very first night that they had sex together, not even caring whether I saw or heard. But in their view—the view of “normal” people—this was only an emergency outlet, with nothing queer about it.

As if you could divide homosexuality into normal and abnormal. I later had the misfortune to discover that it wasn’t only these two gangsters who had that opinion, but almost all “normal” men. I still wonder today how this division between normal and abnormal is made. Is there a normal hunger and an abnormal one? A normal thirst and an abnormal one? Isn’t hunger always hunger, and thirst thirst? What a hypocritical and illogical way of thinking!

Isn’t hunger always hunger, and thirst thirst?

Two weeks later, my trial was already up, justice showing an unusual haste in my case. Under Paragraph 175 of the German criminal code, I was condemned by an Austrian court for homosexual behavior, and sentenced to six months’ penal servitude with the added provision of one fast day a month.

Proceedings against the second accused, my friend Fred, were dropped on the grounds of “mental confusion.” No exact explanation was given as to what this involved, and it was clear enough from the judge’s face that he was less than happy with this formula. Never mind, in Hitler’s Third Reich even the judges, supposedly so independent, had to adapt to Nazi reasons of state.

Some “higher power” had put in a finger and influenced the court proceedings. Presumably Fred’s father had used his weight as a Nazi high-up, and managed to get his son out of trouble.

For my part, however, I was later to find that the same “power” continued its persecution after my sentence was up. I was not to be released again, so that no one would know that the son of a high Nazi party and state leader was homosexual and mixed up in a criminal trial. It then became clear to me why the Gestapo had involved itself in a harmless “queer case.“[1]

I never found out whether Fred had been interrogated by the Gestapo, nor did I see him in court. He was referred to throughout simply as the second accused, and never mentioned by name. He vanished from my sight, and remains so today. After 1945, I tried to find out what had become of him and whether he was still alive, but in vain. His father is said to have shot himself at the end of the war.

I was transferred to the Vienna district prison to serve my sentence. Once again the same bodily examination as in the police station, then I was put in a single cell. Only two days later, however, I was assigned for domestic work on my floor, as a “faci” in the prison slang. Three times a day I had to serve meals, going from cell to cell, accompanied of course by a warder, and once a week I had to collect all the prisoners’ shirts and give out clean ones. Every day I had to wash the corridors morning and afternoon, and do whatever other services might be needed by the warders (happily though not sexual services!).

This work made my time in prison very much easier. And on top of this, we facis were only locked in at 6 p.m. and our cells opened again at 5 a.m., even if we were only permitted to leave them when we had work to do.

In this way I came into contact with many prisoners, and often helped smuggle messages from one cell to another. Several times I had to serve someone condemned to death their last meal, generally a wiener schnitzel and potato salad, knowing that at 4 a.m. the next morning they would be hanged or beheaded. Some of them were political prisoners, resistance fighters against the Nazi regime. I later learned in concentration camp that the Nazis had subsequently abolished even this little humanitarian gesture.

Through these contacts with political detainees, Jews, criminals, and others like myself I discovered a great deal about the misery and suffering inflicted by the Nazis. Up till then I had known very little of the martyrdom of these victims, and this made me stronger and more mature, helping me to bear my long years in concentration camps.

In the Vienna prison, however, we were treated with perfect correctness. Even though the warders were strict in enforcing regulations, they often had a friendly word for us prisoners. Not once during my six months there did I hear of a prisoner being beaten.

On the day that my six months were up, and I should have been released, I was informed that the Central Security Department had demanded that I remain in custody. I was again transferred to the “Liesl,” for transit to a concentration camp.

This news was like a blow on the head, for I knew from other prisoners who had been sent back from concentration camp for trial that we “queers,” just like the Jews, were tortured to death in the camps, and only rarely came out alive. At that time, however, I couldn’t, or wouldn’t, believe this. I thought it was exaggeration, designed to upset me. Unfortunately, it was only too true!

And what had I done to be sent off in this way? What infamous crime or damage to the community? I had loved a friend of mine, a grown man of twenty-four, not a child. I could find nothing dreadful or wrong in that.

What does it say about the world we live in, if an adult man is told how and whom he should love? Isn’t it always those lawmakers who are sexually inhibited and have inferiority complexes who raise the loudest hue and cry about the alleged “healthy feelings” of their fellow citizens?

This piece is excerpted from The Men With the Pink Triangle: The True, Life-and-Death Story of Homosexuals in the Nazi Death Camps, available from Haymarket Books.

A previous version of the introduction misstated the estimated number of people imprisoned in concentration camps for homosexuality.

This is of course true, but dispatch to concentration camp, or Schutzhaft (protective custody) in the Nazi euphemism, was by this time automatic after a prison sentence for homosexuality.

Heinz Heger was the pen name of Hans Neumann, a writer who recorded the experiences of Josef Kohout, an Austrian survivor of the Holocaust who died in 1994.

David Fernbach is a freelance writer, editor, and translator. His publications include the three-volume edition of Karl Marx’s Political Writings and The Spiral Path: A Gay Contribution to Human Survival. His translations include Marx’s Capital, volumes two and three, and works by Georg Lukacs, Rudolf Bahro, Boris Groys, Nicos Poulantzas, Pierre Bourdieu, Alain Badiou, and Jacques Rancière.