The Jewish Case for Open Borders

How center-left immigration proposals lead to far-right policy.

IMMIGRATION HAS BECOME so central to US politics today that it’s hard to remember how rarely it flickered into the national spotlight before 2016. Prior to Donald Trump’s election, both parties agreed on the need for border enforcement, with the GOP routinely accusing Democrats of being soft on “illegals” and the Democrats responding with vigorous deportation campaigns. But the explicit racism of the Trump era, with its Muslim travel ban and the daily outrages of family separation and detention, has galvanized a large-scale protest movement. Jews have been especially active in this mobilization, driven by their social liberalism, their sense of religious duty, or both. Synagogue networks sprang up to offer aid to refugees, while groups like Jews United for Justice and Jewish Voice for Peace have been a visible presence at protest rallies. The role of Trump advisers Stephen Miller and Jared Kushner has at times made the fight seem unusually personal—even familial. Miller’s uncle, a neuroscientist, has been welcomed onto the public stage for his denunciations of his nephew’s immigration policies, which the elder Miller has characterized as hypocritical: the Millers’ not-so-distant Jewish ancestors were, of course, immigrants themselves.

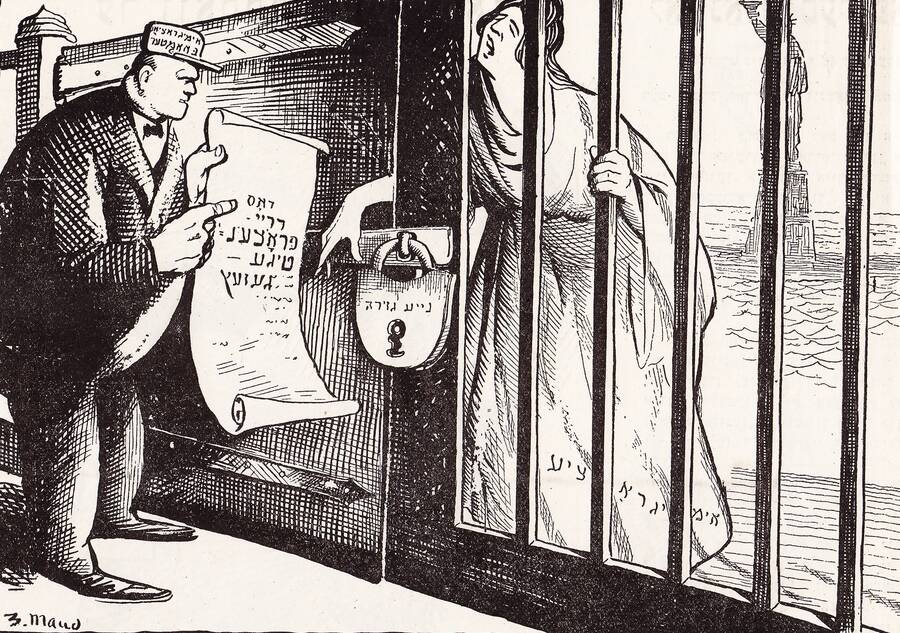

The fact that American Jews are mobilized on behalf of migrants like never before is an important step in the right direction. And, as the charge of hypocrisy against Stephen Miller would suggest, it is not hard to dismantle right-wing immigration arguments by appealing to a Jewish conscience rooted in communal memory. The policies that Trump supports draw on the same logic as the closed-borders isolationism that led the United States to reject Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust. After World War II, this profound moral crime was addressed with the creation of the refugee asylum system—the very system that Central American migrants invoke as they seek refuge in the United States.

Yet there are still limits on the way the mainstream Jewish community approaches this topic. Liberal Jewish discussions of immigration reflect on the religious duty to help refugees, but avoid thinking through just how far this duty might extend—as if obligations petered out after a quota of a few tens of thousands. These discussions bemoan Trump’s concentration camps, but rarely take Bill Clinton and Barack Obama to task for creating and expanding the modern apparatus of detention and deportation. The community questions border-wall rhetoric at home, but rarely the even more militarized separation barrier that defines the politics of Israel. In short, these conversations have danced around the central question: is there such a thing as a border that is both strong and just? The historical record and present-day realities suggest that there is not, and that what we need is not immigration reform, but open borders.

THE CONCEPT OF a Jewish case for open borders may sound like a contradiction in terms even to those progressive Jews who are sympathetic to migrants. In an era of mass refugee flows, terrorism, and economic globalization, open borders suggest something dangerously extreme—a right-wing caricature of the left. And surely of all groups, Jews might well be among the most wary of the political consequences of adopting such a radical point of view. Haven’t we been called “rootless cosmopolitans” and slandered as perennially disloyal for not being sufficiently devoted to the defense of home and country? The gunman who massacred Pittsburgh synagogue congregants last year acted on the white nationalist conspiracy theory that Jewish puppet-masters are implementing liberal immigration policies in order to bring about “white genocide.” Shouldn’t we be chastened by the fact that anti-immigrant ideologues already have Jews in their crosshairs?

To understand why open borders are necessary, we have to understand why center-left immigration arguments—which on the surface appear compatible with the pro-migrant politics of progressive Jews—rest on the same foundation as those made by the right. For center-leftists, wealthy countries like the US have a moral obligation to let in refugees, but that obligation is not unlimited. To determine who is most worthy of being admitted, these countries have to decide whether migrants are running for their lives—say as victims of religious or political repression—or simply seeking better jobs. Within the latter category, too, there is a scale of value, in which wealthier, more educated immigrants are deemed more desirable.

Rank-and-file progressives don’t usually think of the immigration policies they support—expanding refugee quotas, easing restrictions on some classes of immigrants, and ending family separation—as an endorsement of detention, deportation, and racialized terror. Yet these proposals are organized around their own set of structural inclusions and exclusions, and necessitate their own rigorous policing. This is why the border enforcement apparatus grew rather than shrank under the last two Democratic administrations. (The first year the US deported more than 100,000 people was under Clinton in 1997; that number reached its peak of 438,421 under Obama in 2013.)

The ideal immigration policy for a center-left politician (including all the current leading Democratic primary candidates) would ensure that favored economic migrants and some refugees receive preferential treatment. But in order to avoid letting in “too many” people, it would also crack down harshly on poor people without pre-existing support networks or professional credentials, necessitating tactics which range from forcing employers to electronically verify documentation status to detaining and deporting those immigrants deemed expendable. After all, immigrants must be held somewhere while their worth is determined, and must be sent back if they don’t make the cut. Ideologically, there is little daylight between seeing nonwhite people as a threat to white supremacy and poor people as a threat to a privileged national community, especially as the two groups of migrants often overlap. It is no surprise, then, that Obama and Clinton permitted most of the same abuses as Trump, if not with the same overtly racist glee.

Just as center-left border policy in the US perpetuates right-wing policy by another name, the two-state solution in Israel/Palestine—the center-left’s answer to the region’s enduring border crisis—is no longer conceivable outside the far-right status quo. A de facto one-state solution is now effectively inevitable, because the Jewish state, led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his allies in the settler movement, has come to include the entire territory of Israel/Palestine in its imagined birthright. Attempts to rebut this notion electorally have failed, and its promoters rightly regard outside attempts to broker a solution as toothless. A version of Zionism from the 1940s might perhaps have coexisted with an equal Palestinian state, but its mature version, fed by military victories and unwavering American support, no longer can. Even the remaining supporters of a two-state solution can offer only a shrunken, nostalgic version of Zionist nationalism. And what nationalist, offered the chance for a Greater Israel that stretches from the river to the sea, would instead choose a defensive, cowering alternative?

Yet the dream of a two-state solution continues to serve a purpose: the territorial institutions that were once supposed to deliver Palestinian independence—specifically the Palestinian Authority—have been perverted into instruments of subjection, administering and entrenching the occupation as they wait for a state that will never arrive. Meanwhile, “dangerous neighborhood” rhetoric about the external threats to Israel serves to legitimize the permanent state of emergency and the intensified militarization of Israeli society. The borders between Israel and Palestine exist definitively for the have-nots, not the haves; Israelis have freedom of movement and settlement while Palestinians must waste years of their lives on identity checks, migration controls, and deliberately exclusionary bureaucratic procedures. Likewise, Israel’s 2005 withdrawal from Gaza was portrayed as a unilateral good-faith effort to meet the two-state solution halfway, but under the cover of this rhetoric, it has simply replaced direct occupation with a permanent and devastating state of siege. The ghost of the two-state solution feeds the reality of Israeli repression.

This de facto “one-state reality” has led many commentators to conclude that the only alternative is to organize for a single state that is both democratic and secular. The details of this process will be messy, but the South African example—disproving warnings of “white genocide” that circulated on the right in the 1980s—suggests that there is little reason to fear the end of Jewish life in a binational state. Explicit constitutional guarantees of collective representation for major ethnic and religious communities, as in post–civil war Lebanon, will be necessary to protect binationalism, though the precise nature of these will not become clear until long into the future. While no historical precedent can fully guarantee a future in which Israeli Jews are safe, the alternative is to embrace the politics of fear, justify a tyrannical status quo, and capitulate to the suffocating ethnonationalist drift of Israeli politics. This is a moral failure as grave as Miller’s support for Trump.

The most immediate result of a democratic solution for Palestine would be a fundamental redefinition of Israeli/Palestinian statehood and an equally monumental shift away from the logic of border enforcement. This solution would create a state, of course, and this state would probably retain some border controls, but the internal borders and Palestinian migration restrictions that now shape life in Israel/Palestine would disappear. Like many other states, Israel allows a person to claim citizenship without being a child of citizens or born in its territory; unfortunately, this right is limited by a highly exclusive ethnic criterion—it only applies to Jews—and is subject in practice to additional racialized logics, since nonwhite Jews who wish to immigrate face disproportionate scrutiny. An Israel/Palestine for all its people would add the right of return for Palestinian refugees to this Jewish right of return, significantly expanding the boundaries of its national community. It would deracialize Israeli/Palestinian identity and recognize instead the existing diversity of people living between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea—from Arab Christians to Palestinian Jews to Druze to other groups with ancestral connections all over Europe and Asia. Such possibilities show us that an open-borders perspective is not just a tactical intervention in a debate about immigration, it is a new vision of a more just society.

LUCKILY, Jews in search of an answer to Trump, Netanyahu, and their far-right supporters around the world need not be constrained by center-left, Democratic, and liberal Zionist visions of what it means to be both progressive and Jewish. Instead, we should look to the radical alternatives that large numbers of Jews once supported in Europe and in immigrant communities across the world.

To start with, we can unlearn the ways that the Jewish immigrant past has been misremembered. Most popular American portrayals of Jewish immigrants have depicted them as religious migrants, following a long line of faith communities seeking the freedom to worship in peace. But historians long ago concluded that this story is misleading. The vast majority of Jewish emigrants from Eastern Europe were driven by the same mix of economic desperation and social exclusion that drives migrants today. “Pauperized” Russian Jewish immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were pathologized by state institutions and Jewish philanthropists alike as being prone to settling in ghettos and becoming a burden on the state. Only later were their experiences rewritten in a language of religious freedom that concealed the similarities between today’s and yesterday’s migrant populations.

We can also resuscitate the long history of Jewish anti-nationalism. In the 19th century, Jewish communities in Central and Eastern Europe faced a rising tide of nationalist mobilization, both from mass political parties and rulers in search of legitimacy. In response, Jewish activists in the anarchist and internationalist socialist tradition argued that the answer was not to build a Jewish state, but to seek Jewish emancipation as part of a broader anti-capitalist movement. The vast majority of Jews had more in common with Latvian, German, or Russian workers than they did with the few wealthy and powerful members of their own community, and Jews joined revolutionary socialist parties in the Russian Empire in disproportionate numbers. Even in a specifically Jewish socialist party like the Jewish Labor Bund, nationalism was anathema. “Cosmopolitans from head to toe, they refused to even touch upon national questions,” one skeptical Bund member recalled of the comrades who gathered at a party congress in 1899. “For them, anything that smelled of nationalism, with any relation to national problems, was treyf.” Even the less hard-line Russian Bundists of later years advocated cultural autonomy, never a territorial state.

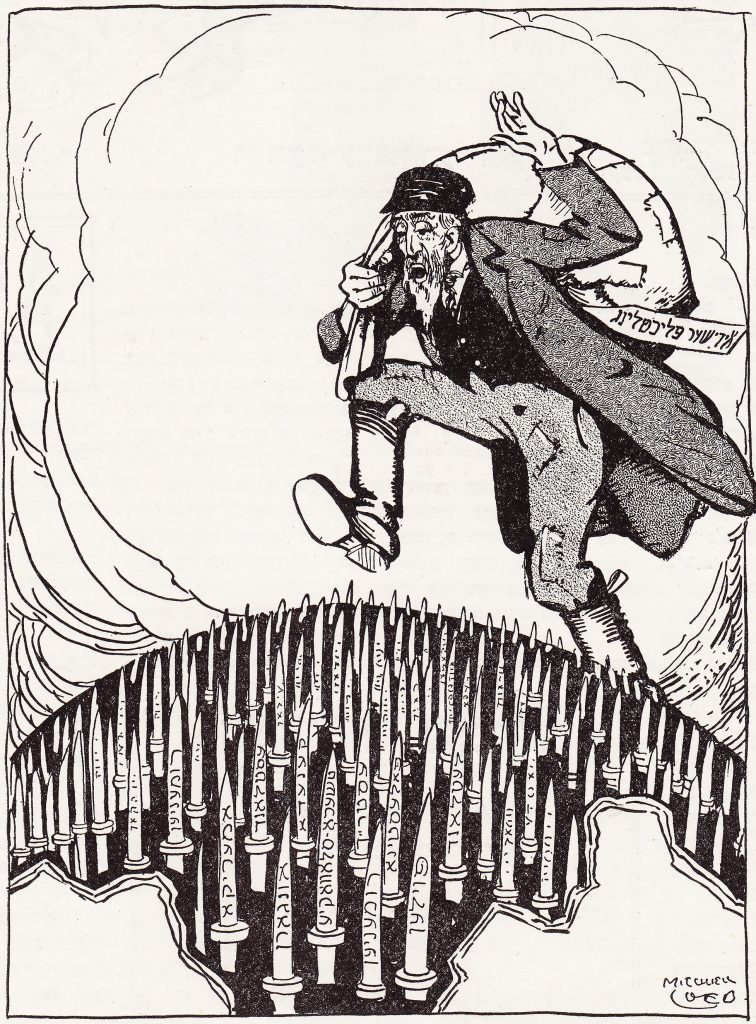

Many of these Jewish radicals, whether anarchists, communists, or socialists, retained their loyalty to the international working class when they immigrated to the United States. Their internationalism only grew stronger as they built connections in US cities and organized their workplaces and neighborhoods. Often, they maintained links with their communities in the Pale of Settlement and elsewhere; some even went back and forth, not yet restricted by the anti-Jewish immigration quotas that would be instituted after World War I. Jewish immigrants came together with other foreign-born groups in organizations like the Industrial Workers of the World, helping to create one of the cornerstones of the American left. These left-wing Jews were among the earliest targets of the first Red Scare that followed the Russian Revolution. Woodrow Wilson’s Palmer Raids swept across the country, deporting immigrants who refused to abandon solidarity and internationalism in their new country.

Even Zionism itself once had anti-statist components. Most Zionists hoped for a state of their own, but early in the 20th century, writers like Hillel Solotaroff and Chaim Zhitlowsky, both Yiddish-speaking immigrant intellectuals in New York, imagined another alternative: a federation of self-governing anarchist communes in Palestine that would defend Jewish life without relying on state power. Like many commune-builders in the US, such anarcho-Zionists were often guided by unexamined settler colonial assumptions that posited Palestine as empty or Palestinians as inconsequential; some adopted a left-wing version of the colonial “civilizing mission,” envisioning the local population as ripe for uplift by “radical” invaders. Yet the influence of anarchism even in this milieu suggests how deeply rooted skepticism about states and borders had become in the Jewish community at the beginning of the 20th century.

By midcentury, after the catastrophe of World War II, the nationalist side of the debate on the future of Jewishness seemed to have won. Members of the anti-nationalist Bund were massacred in the Holocaust, marginalized by Soviet antisemitism, or co-opted into capitalist societies. Organized Jewish communities on the western side of the Iron Curtain pledged allegiance to the United States and Israel. A similar consensus formed in the Soviet Union. Despite its internationalist rhetoric, the postwar era in the USSR was one of nationalist consolidation, even to the point of rehabilitating the imperial legacy of Russia’s monarchs. (In 1958, May 28th was proclaimed “Border Guards Day,” celebrating the KGB troops who watched over Soviet borders.) Across the board, Jews who dissented from the nationalist consensus were disciplined through the deployment of an old trope: the notion of Jews as cosmopolitans without roots in any national community. The power of this accusation came from a long-established perception that Jews lacked loyalty, that they behaved as guests in the nations that hosted them; the Protocols of the Elders of Zion explicitly contrasted the “international force” of the Jews with the “national rights” they allegedly sought to destroy. Jewish communities in the Soviet Union, the United States, and Israel all internalized these narratives as a foundational trauma, and invested in territorial nationalism as the only way to prevent a repeat of the Holocaust. The utopian internationalism of the early 20th century was abandoned. Both within the Jewish community and outside it, the impulse to impose national bounds on Jewish political thought seemed inescapable.

What once seemed like a solution to Jewish vulnerability has now become a form of complicity with newly virulent ethnonational projects. The specific forms of national loyalty that Jews developed in the 20th century are losing their usefulness: the lines between far-right and center-left ideology are beginning to blur around the critical juncture of borders. The way out of the nationalist trap in which Jews have been caught since World War II goes through Jewish cosmopolitanism, but not in the form that antisemites have imagined. The idea that Jews are more loyal to Jews in other countries than to their fellow citizens should be replaced by a recognition of our duties to all human beings, not just those on the inside of the fortresses we increasingly inhabit. Only an authentic internationalism that understands what we have in common with the Polish migrant laborer, the Central American refugee, and the Syrian asylum seeker can counterpose a politics of solidarity to the politics of chauvinism. The gap between this awareness and the reality of the current border structure seems unbridgeable, and only years of organized collective action can help us overcome it. But the first step is to recognize that there is no center-left solution to the problem that borders pose. It was center-leftists who made the concrete, and the fascists have only to pour it.

Greg Afinogenov is assistant professor of imperial Russian history at Georgetown. His first book, Spies and Scholars: Chinese Secrets and the Pursuit of Power in Imperial Russia, is forthcoming next spring from Harvard University Press.