The Illustrated Kafka

Peter Kuper’s latest collection mines Kafka’s scenes of anxiety, authoritarianism, and the anomie of modern life.

Discussed in this essay: Kafkaesque: Fourteen Stories, by Peter Kuper. W. W. Norton & Company, 2018. 160 pages.

DON’T BLINK. “He who blinks sees only complications,” says the steward in Franz Kafka’s contorted short play, The Warden of the Tomb. For Kafka, complications are always crippling. They ensnare, divert, and confound; they leave his characters helpless to achieve what they profess to want. Kafka’s interest in such interior struggles makes his material difficult to realize in another medium. This hasn’t stopped comics agitator Peter Kuper, one of the founders of World War 3 Illustrated, a left-wing comics magazine, from bringing his formidable talent to bear on the challenge. His latest collection, Kafkaesque, offers an opportunity to try to see Kafka with fresh eyes, unblinking.

The collection’s title, at least, has the opposite effect. The transformation of an author’s name into an adjective might be history’s greatest compliment, but it contributes little to appreciation of their actual work; readers engage with the received idea rather than what’s before their eyes. Cynthia Ozick called the word “the denigration of an imagination.” Philip Roth derided it as “plastered indiscriminately on almost any baffling or unusually opaque event that is not easily translatable into the going simplifications”—think Brexit, or the American healthcare system, or any other sufficiently obscure bureaucratic proceeding. Kuper isn’t immune to this overly familiar, overly simplistic reading, but he’s also attuned to a more complicated one. He first took on the task of adapting Kafka over a decade ago; a previous collection, Give It Up! And Other Short Stories, consists of nine of the 14 pieces that appear in this new edition. In both collections, Kuper swaps his usual vibrant palette—the electric aerosol aesthetic of The System, his wordless fever dream of life in fin-di-siècle, neoliberal New York—for a rich black and white. In rough-hewn forms intentionally recalling expressionism and woodcut, Kuper gives us the Kafka with which we think we’re familiar. But he never reduces the stories to caricature.

Adaptation from one medium to another is often a process of distillation, of whittling a work down to its most essential elements. Kafka left behind a mass of shorter work—some categorizable as full-fledged short stories or novellas, others more like fragments or parables (some of which resurface in his novels). This material allows Kuper to adapt without significant redaction; more than half of Kafka’s texts are brief enough that Kuper uses almost every word. His interest in Kafka is grounded, in part, in the latter’s appreciation of the authority of brute force—the looming, malevolent figures who overawe the narrators of “The Helmsman” or “Give It Up!”. For Kuper, these stories are a scaffolding for his long-standing condemnation of state power, violent repression, and the anomie of modern life.

For Kafka, this disaffection has older, deeper roots. One of the highlights of the volume is the chance to see Kuper take on “Before the Law,” a piece not included in the earlier collection. Kafka’s parable originally appeared in the midst of the First World War and was later incorporated into his draft of The Trial. “Before the law stands a gatekeeper,” it begins in the translation Kuper uses for his take. The man from the country who asks to be admitted gets no further. Kuper’s supplicant is black; his gatekeeper is white. This decision recasts the story as an allegory of racial justice deferred. As critical as that analysis is to our current moment, Kafka has something else in mind: when the man first inquires if he can enter, the gatekeeper steps aside and tells him “just try to go in despite my objections.” The man blinks, and all his subsequent efforts to convince and plead and negotiate come to nothing after that first failure of nerve. It’s not the gatekeeper who keeps the supplicant from the law: it’s the blink, provoked by the promise of the law handed down from on high. The law prevents its own realization.

In “A Little Fable,” Kafka’s mouse makes its way through a maze of Kuper’s design. The mouse’s original lament, less than a hundred words long, confronts the terrifying freedom of the seemingly infinite space it enjoys at first, and then the false comfort it finds between the walls as it approaches its inevitable end. Kuper plays with blending word and image: the panel borders mark time while doubling as the maze’s walls, with lines of the story occasionally printed directly on them. His compositions are still so easily legible that it’s easy to skim right over the fact that the world the mouse runs across, that was “at first . . . so wide,” is actually its own head.

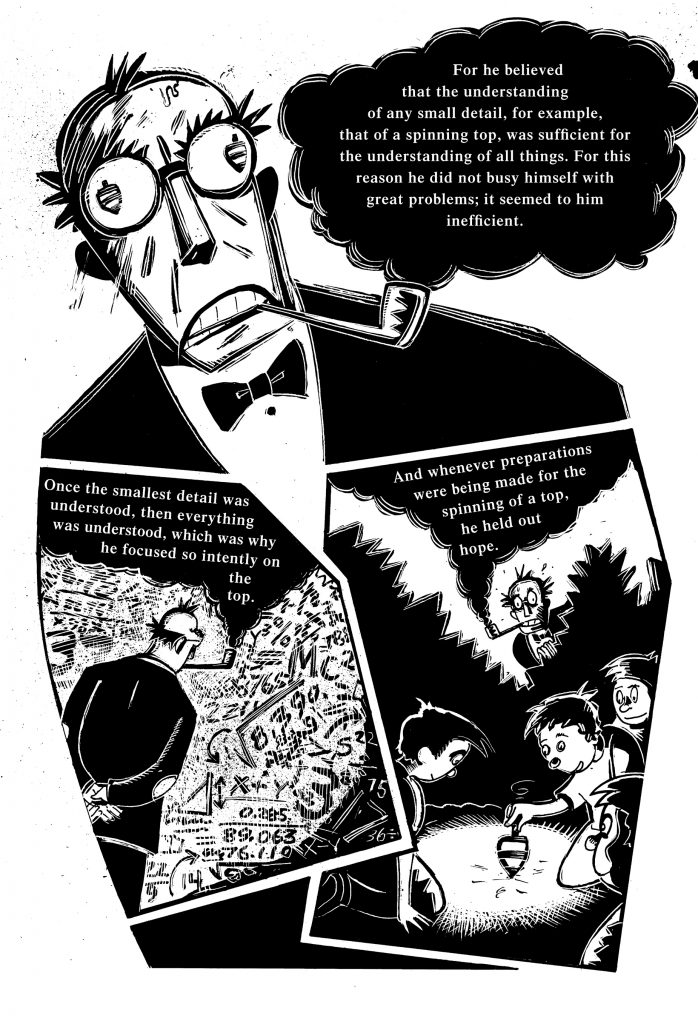

“The Spinning Top” comes soon after, ensnaring the reader in the mind of another character—a professor—propelled by urges beyond their control or even understanding. Kuper focuses on the professor, wild-eyed and feverish, as he waits to seize a top from a group of children, hoping its trajectory will explain the fractured, fractal logic of life itself. The visualization of Kafka’s obsessed professor stalking kids for their top imbues the story with a sense of menace that’s more easily overlooked in the original, if it’s even present at all. The comic’s second page lays out the professor’s obsession: Like the mouse dashing for safety, it’s another unified composition, in which the professor’s body contains the second and third panels. His body is shaped suspiciously like a top, already off-kilter, wildly gyrating before toppling over. The interior world shapes the exterior one.

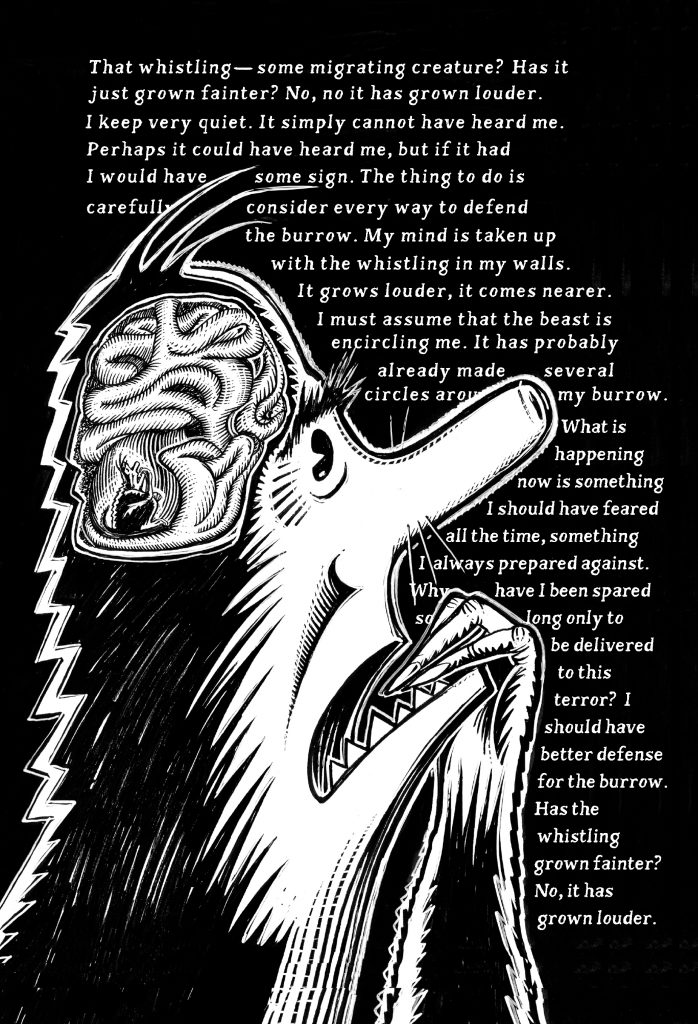

Which brings us to “The Burrow,” in which Kafka’s mole-like narrator drags readers deep into the soil of its own mind. Here Kuper has carved down 35 pages of manic, paranoid digression—at one point Kafka unspools a single paragraph over seven pages—into a comic half that length. He mostly succeeds. The narrator seems to have spent a lifetime digging its burrow, a central chamber “so spacious that food for half a year scarcely fills it”—stores it must defend from “countless” enemies, within and without. Kuper renders this acquisitive character literally: its den is decked out with a flat-screen TV, its stores become shelves of canned food, its hunting trip outside of its tunnels becomes a trip to the supermarket. It’s an easy indictment of consumer capitalism, of how the desire to acquire can never be satiated, how the effort to dig down and defend your patch only reinforces the fear of what’s outside it.

“I lose myself for a moment in my own maze,” Kafka’s narrator says in the original story, seemingly offhand. Kuper’s indelible penultimate image digs into the line, recalling the mouse scampering over its own skull, the philosopher spinning out of control: The narrator, set against a solid wall of text, desperately chews its nails in fear, a cutaway of its skull revealing the folds of its brain, which have become those of the burrow. At the center of this labyrinth quivers the narrator.

Throughout these stories, Kuper draws their tortured protagonists with jagged interior lines, syntagmata connoting their inner distress, the high-voltage tension running through their bodies. The mouse hurrying through the maze, the professor chasing his top, the burrower hunkering ever further down, even the man from the country waiting in vain for the revelation of the law—all exist in states of livewire agony and anticipation all betrayed by the very sources from which they sought solace. In his strongest moments, Kuper works past his own political preoccupations to a more existential dread, to Kafka’s fundamental truth: We are caught in traps of our own devising.

Don’t blink.

Nicholas Jahr is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn and a member of Jewish Currents’ editorial board. In the past he has written for the magazine about comics, film, the diaspora, Israeli elections, and Palestinian nonviolence. His work has appeared in the International New York Times, The Nation, City & State, and the Village Voice (RIP).