UC Berkeley’s “Bears for Israel” students stage a counter-protest against the school’s Students for Justice in Palestine’s 2015 Day of Action.

The Fight for the Future of Israel Studies

Donors view Israel studies as a vehicle for countering Palestine activism on campus. But many of the scholars they fund don’t toe the line.

Last May, after Israel carried out a deadly assault on Gaza, a group of professors in Israel and Jewish studies circulated a statement of condemnation. Liora Halperin, a historian of Israel/Palestine and chair of the Israel studies program at the University of Washington, was one of more than 200 professors who signed the letter—which critiqued the influence of “settler-colonial paradigms” on Zionism. “I felt like it needed to be said,” Halperin, whose own work focuses on Jewish–Arab encounters during the British Mandate period, told me. “I felt I had a lot of people who were looking to me as a leader, as a guide. I decided I couldn’t be silent.” Halperin knew that her signature might upset some of those people, including Becky Benaroya, the prominent local philanthropist who had endowed her chair. But Halperin assumed that she and the donor could discuss their disagreements, as they had in the past; she wasn’t worried about endangering her job or program: “I thought, ‘It’s a permanent endowment. The money isn’t going anywhere.’”

Benaroya had given the $5 million endowment in 2016, in a moment when Seattle’s Jewish community was up in arms about what they perceived as the university’s pro-Palestine bent, epitomized for them in a 2015 campus talk by Omar Barghouti, co-founder of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement. “We had a sense that sure, academic freedom, people have a right to speak, but you can’t present one side of the story. Things were in a state of unbalance,” Sonny Gorasht, who was involved in a community advisory board for UW’s Jewish studies program, would later tell the local Jewish newsletter The Cholent. As his daughter and fellow advisory board member Jamie Merriman-Cohen later wrote in a letter to UW President Ana Mari Cauce, the chair “was advocated for and funded with the intention of offering a safe and open space for intellectual curiosity about Israel that would strengthen, not undermine, its very existence.”

From the beginning of her tenure, Halperin, a rising star in the field of Israel studies who was selected by a faculty committee in 2017, attracted the ire of some community members. Gorasht told The Cholent that he called the head of Jewish studies to complain after seeing that her course listings referred to Israel/Palestine rather than Israel. Benaroya, though, seemed content: In March 2021, she emailed Halperin praising the Israel studies program and professing Halperin to be “definitely worthy of the position,” according to public records released by the university. But after she signed the May letter, Halperin heard through a UW regent that she had displeased Benaroya; at the donor’s request, she attended two meetings with Benaroya and Cauce, the university president, that summer and fall. Also in attendance were several people the 99-year-old Benaroya had brought as advisers, including Randy Kessler, executive director of the Northwest chapter of the Israel-advocacy group StandWithUs.

Halperin says Cauce told her before the second meeting that the university was considering returning Benaroya’s money if they couldn’t allay the donor’s concerns, but if necessary would find another way to fund the chair position and program. When the group sat down again, one of Benaroya’s advisors, Michael Schuffler, an emeritus medical school faculty member and a small donor to the Jewish studies center, laid out her demands: Benaroya wanted Halperin to refrain from making political statements “derogatory of Israel,” according to notes that Schuffler later emailed to then-Jewish studies chair Noam Pianko. She also wanted Halperin to teach courses about Israel, not Israel/Palestine. Asked for examples of courses that would fit the bill, Schuffler suggested “the history of U.S.-Israel relations, the history of relations between Israel and Arab countries, the history of how Israel went from a 3rd world country in 1948 to a 1st world country today, and courses dealing with Israeli high tech.” Benaroya “wanted [courses and public programs] about positive things that Israel was doing,” Halperin said. She asked, according to Halperin, why Halperin was directing “all this attention to political stuff.”

Cauce told Benaroya that the university could not restrict faculty speech; instead, throughout the fall, Halperin worked with UW administrators to try to find other ways to repair the breach. In October, Halperin and Benaroya went out to lunch one-on-one. Benaroya emailed Halperin afterwards to say she had “enjoyed . . . getting to know each other better.” Halperin and Pianko drew up a charter for a new advisory committee that would give feedback on an annual public lecture that Halperin organized. But when Halperin returned from winter break, she received word in an email that Benaroya had asked the university to return her money, and UW had agreed. A few weeks later, she was told that, contrary to what Cauce had assured her in the fall, the funding for her endowed chair would not be made whole: Though her salary would remain the same, most of the program’s money for research, public events, and graduate student support was gone. Alarmed, Halperin began alerting her colleagues. By the end of February, hundreds of Jewish and Israel studies scholars around the world had signed a letter accusing UW of violating the “bedrock principle” of free expression. The Association for Jewish Studies, the Middle East Studies Association, and the UW chapter of the American Association of University Professors wrote letters to Cauce warning that the university was endangering academic freedom. In early March, UW announced that it would restore all funding to Halperin’s now nameless chair in Jewish studies. (“Professor Halperin’s academic freedom as a professor and scholar was never in question, and the UW made clear that the University will not allow outside influences to impede on our scholars’ research,” UW spokesperson Victor Balta said in a statement to Jewish Currents.) Meanwhile, The Cholent reported that Benaroya was planning to give the $5 million that UW had returned to her to StandWithUs.

“Donors think of buying an academic like you buy a used car: someone who will do your bidding and protect Israel from any criticism.”

Students for Justice in Palestine activists at UC Berkeley set up a mock Israeli checkpoint demonstration during the group’s 2016 “Palestine Awareness Week.”

The UW controversy is the most visible example to date of the struggle roiling the academic field of Israel studies, in which scholars, donors, and advocacy groups jockey over what it means to conduct rigorous study of the State of Israel on college campuses, primary battlegrounds in the political fight over Israel/Palestine. Most of the Israel studies chairs and centers in the Anglophone world were established in the early 21st century by donors who wanted to counter what they perceived as an “anti-Israel” intellectual climate fueled by radical Middle East studies professors. Much of the enthusiasm for Israel studies was stoked by one organization, the American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE), whose crusading director Mitchell Bard saw it as his mission to improve Israel’s image on campus. Bard’s own funding came from major players in Jewish philanthropy such as the Schusterman Family Foundation, which also supports Israel-advocacy projects like the Israel on Campus Coalition, and which has been instrumental in funding professorships. “Donors think of buying an academic like you buy a used car: someone who will do your bidding and basically protect Israel from any criticism,” said Gershon Shafir, a professor of sociology at UC San Diego and a prominent theorist of Israeli settler colonialism. The work of advocates and donors has contributed to the creation of new faultlines in the field and its primary membership organization, the Association for Israel Studies (AIS), which has been rocked by debates about how Israel studies scholars should relate to the politics of the Zionist project.

Today, well-funded groups like the Israel Institute—another project of the Schusterman Foundation—continue to exert influence over the field. While the institute says it funds scholars of all political persuasions to teach Israel studies on US campuses and does not interfere with the content of their courses, it sometimes attempts to influence the hiring processes for positions it supports. In 2017, for example, when the Israel Institute provided funding for a new tenure-track position at the University of Florida, its agreement with the university included a provision requiring someone external to UF to join the search committee in a consulting role, as Israel Institute President Ariel Roth confirmed in an email to me. The institute nominated Kenneth Stein, the director of Emory University’s longstanding Israel studies program, who was then a member of the institute’s advisory board. Jack Kugelmass, then the head of UF’s Jewish studies department, said that he pushed back against the inclusion of an external professor, and Roth confirmed that the Israel Institute agreed to drop that provision the following year. Tamir Sorek, an Israel studies scholar who was employed at University of Florida at the time and is now a history professor at Penn State, believes that donor intervention into hiring processes is common: “In many cases, donors have been able to influence faculty selection, and where they failed, they learned for the future how to better influence the process.” As a result, he said, “most of the positions in Israel studies established over the past decade do not take a very critical stance.”

But while some Israel studies professors may be outspoken in their support for the state—and their criticism of campus Palestine advocacy—much of the scholarship winning acclaim in the field questions the bedrock narratives of the Zionist movement. “A significant number of people with Israel studies positions are not doing Israel advocacy—what they do actually upsets people who want them to do advocacy,” said Yair Wallach, a lecturer in Israel studies at SOAS University of London who signed the same letter as Halperin in May 2021. “At some point it was clear that things were going to come to a head between donors and the academics.” Indeed, some Israel-advocacy groups today view Israel studies as a lost cause. “Jewish and Israel studies promote a negative view of both Jewish civilization and Israel . . . they have become almost indistinguishable in their politics from the highly politicized Arab nationalist Middle Eastern studies department,” Scott A. Shay, a New York banker who has served as a board member for Jewish organizations like the UJA-Federation, wrote in a recent, representative op-ed in eJewishPhilanthropy. This presents a possible dilemma for critical Israel studies scholars, many of whom applied for postdocs and endowed chairs in the field—rather than in, for example, history or political science—because it was flush with resources in an otherwise anemic academic job market. As progressive scholars carve out space for themselves within Israel studies, they risk losing the donor support that made their positions attractive in the first place—a catch-22 that speaks to the state of the contemporary university, where a decline in public funding has heightened reliance on donors’ largesse.

These circumstances can produce situations like Halperin’s. Though her own position is safe, and funding for the Israel studies program has been restored, she laments the fact that the public funding now being directed toward her salary “could’ve been used to hire a new faculty member, or to support graduate students” elsewhere in the university. She continues to worry about the episode’s broad implications. “It’s a really chilling precedent,” she said. “I didn’t express the political views the donors wanted, and then a bunch of money went away.”

Liora Halperin, professor at the University of Washington.

“It’s a really chilling precedent,” Halperin said. “I didn’t express the political views the donors wanted, and then a bunch of money went away.”

In 2005, when Halperin was in the first year of a PhD in Jewish and Middle East history at UCLA, she learned that a new initiative of AICE was offering $15,000 grants to graduate students working in the field of Israel studies. Halperin wasn’t even sure if her work qualified, since she was researching the Mandate period in Palestine, which predated the founding of the State of Israel. Tempted by funds nearly equaling her grad student stipend, she applied anyway and received the grant. As part of the program, she was expected to attend the yearly AICE conference, where she heard Bard, the director, speak for the first time. Bard, bald and bespectacled, with a genial manner and a penchant for professorial blazers and turtlenecks, welcomed the students into his fold. “He gave speeches about the importance of Israel studies scholarship in combating anti-Israel activity on campus, and about the ‘non-scholarship’ going on in Middle East studies and ‘good scholarship’ coming out of Israel studies,” Halperin recalled. “I remember sitting there being like ‘Wait, what? Where am I? How did I end up in this room?’”

Halperin met Bard during a phase of explosive growth for Israel studies, marked by enthusiastic donor involvement. During and shortly after Israel’s founding, most work in the field was undertaken to serve the needs of the state and the Zionist movement; sociologists in particular “played an important role in designing and envisioning the Israeli state,” according to Shafir. But there were few spaces for independent or critical study of Israel. As Middle East studies grew after the World War II with the support of major foundations and a federal government interested in bolstering the knowledge of American foreign policy workers, Israel was “peripheral,” according to Zachary Lockman, a historian of the Middle East at New York University. In the ’60s and ’70s, as more radical scholars—many of whom supported the Palestinian liberation struggle—transformed Middle East studies, Israel remained an unpopular subject. Meanwhile, scholarship in the field of Jewish studies, which originated in 19th-century Germany, focused largely on the diaspora.

By the 1980s, however, scholars had begun to take a more critical approach to the study of the state. In Israel, a new generation of academics challenged established narratives about Zionism; scholars like Benny Morris, who analyzed newly declassified Israeli government documents to reveal the military’s role in the 1948 expulsion of Palestinians, became known as “new historians,” while an emergent group of “critical sociologists” like Shafir and Sammy Smooha began to study Zionism as a form of colonialism. In the US, where the only institutions focused on Israel tended to be advocacy groups, a group of scholars came together in 1985 to create an independent scholarly association, the Association for Israel Studies (AIS). “Most of the people in the association were Zionist but we did not want it to be a Zionist organization,” said the political scientist Ian Lustick, whose most recent book, Paradigm Lost, argues for one democratic state in Israel/Palestine. Shafir, who later served as the association’s president from 2001–2003, agreed: “The purpose was to study Israel as one would study any other country or topic, with academic detachment and a critical perspective.” Despite its commitment to independence, the cash-strapped AIS did sometimes take money from the Israeli consulate, Lustick told me, mostly to provide travel funds for Israeli scholars. The association also accepted some money from large Jewish philanthropic foundations like the Littauer Foundation and the Schusterman Family Foundation, a move that Lustick described as controversial among members.

At the dawn of the 21st century, the collapse of the Oslo Process and the eruption of the Second Intifada made Israel an increasingly contentious topic on campus. The emergence of the BDS movement in 2005 provided a rallying point for student activists around the world, who began holding protests and organizing divestment campaigns. In response, Israel-advocacy groups sought to increase their influence on campus, funding travel to Israel for Jewish students and intervening in student government divestment debates. Many in the “pro-Israel” community attributed Israel’s declining reputation among students to an influx of Middle East studies professors, partially the result of funding from Arab countries like Saudi Arabia and Qatar that sought to counter Islamophobia in the US after 9/11. Bard launched AICE’s Israel studies programming in those years with the intention of changing the composition of university faculty. “They’re the most important people on a college campus. They have the most influence,” he told me.

Mitchell Bard, founder of AICE’s Israel Studies Programming

Bard launched AICE’s Israel studies programming in the early 2000s with the intention of changing the composition of university faculty. “They’re the most important people on a college campus. They have the most influence,” he said.

Bard made no attempt to deny that the purpose of AICE’s work was to increase students’ affinity for Israel: In a 2004 op-ed for the Chicago Jewish Star, he laid out his vision for combating “anti-Israel” faculty and educating students “so they can become independent thinkers who love and understand Israel, warts and all.” With the support of Jewish philanthropic foundations, Schusterman chief among them, AICE brought visiting Israeli faculty and postdoctoral fellows to American universities and supported grad students like Halperin. Bard told me that a key component of AICE’s strategy was to increase the number of classes about Israel that didn’t focus on the state’s political status or its relationship to Palestine, in order to “change the perception of Israel as simply a place of conflict.” Sorek sees this as an advocacy tactic in itself: “It’s all about what you’re studying,” he said. “Donors who give money to Israel studies, they want to talk about Israel without Palestinians, to talk about things other than the occupation.” Other Jewish philanthropists also funded visiting scholars: In Illinois, for example, the Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago sponsored programs for visiting Israeli scholars at Northwestern University and the University of Illinois beginning in 2005. The year before its launch, the project’s director, Michael Kotzin, wrote in The Forward that the Federation hoped to ensure that “academically credible offerings that are not unsympathetic to Israel will be made a more standard and universal part of regional university curricula.”

Bard was adamant that his scholars were not lobbying students in favor of Israel: “Even if we had wanted professors to adopt an agenda, they wouldn’t have done it,” he told me. AICE emphasized its willingness to recruit academics with varying political opinions, though Bard said that all visiting scholars were required to “believe that the State of Israel had the right to exist.” In a 2013 study, a group of researchers led by Annette Koren at Brandeis University found that students largely perceived AICE-funded Israeli scholars on eight separate campuses as “balanced” and “neutral,” often saying that professors were careful to give weight to “both sides.” In at least one instance where an AICE-funded professor was perceived as biased, students rebelled. In 2007, Hanna Diskin, an AICE visiting postdoc at George Washington University, quit teaching her “Arab–Israeli Conflict” class in the middle of the semester after students complained to the political science department that she excessively favored Israel, the Washington Jewish Week reported at the time. Diskin, whose expertise was in the history of Christianity in Poland and not Israel/Palestine, had assigned her students an AIPAC publication called Myths & Facts as a textbook; Bard had written its most recent edition.

By bringing Israel studies scholars to campus, AICE hoped to encourage interest in the subject among students, and thus to push administrators and local donors to establish permanent programs. When Koren and her team visited eight campuses with AICE fellows in the 2010–2011 academic year, they found evidence that the strategy worked. “At a prestigious private university, the department chair explained that the presence of the [AICE visiting professor] showcased the need within the department to bring on a full-time faculty member,” the researchers wrote. Bard said he credits AICE with leading at least 14 universities to establish Israel studies chairs or centers. Today, there are 27 centers for Israel studies at public and private universities around the world, and 23 Israel studies chairs in the US, as well as a handful spread across the UK, Canada, Australia, and Germany, according to a list that AICE maintains on its website.

No single funder has done more to further this cause than the Schusterman Family Foundation. In addition to supporting AICE, Schusterman has funded several Israel studies centers directly, including at Brandeis University, the University of Texas, Austin, and the University of Oklahoma. In 2012, Schusterman launched a counterpart to AICE called the Israel Institute, and in 2015, it withdrew funding from AICE to focus on its new effort, which boasts a sleeker, more professional online presence and a larger staff than Bard’s organization. (In a statement, the Schusterman Family Foundation said it “invest[s] in Israel Studies as a multi-disciplinary academic field in which modern Israel is taught and studied with thoughtfulness and intellectual rigor” and creates opportunities for students “to learn about Israel from expert faculty,” but would not answer more specific questions about its work or agree to an in-depth interview.) Like AICE, the Israel Institute—whose founding president, Itamar Rabinovich, is a former Israeli ambassador to the US—funds postdocs and fellowships in Israel studies, provides grants to scholars, and arranges for Israeli academics to visit US universities. In contrast to Bard’s habit of publicizing his goals, the institute’s leaders have stressed in promotional materials that they are not engaged in advocacy or activism. Still, Rabinovich has echoed some of AICE’s rhetoric, stressing the need to avoid teaching about Israel as solely a “nexus of conflict” and arguing that students should be introduced to a “complex, modern Israeli experience, including its dynamic society and economy, its entrepreneurial culture, and its vibrant arts scene.”

No single funder has done more to further Israel studies than the Schusterman Family Foundation.

Lisa Eisen (center), co-president of the Schusterman Family Foundation, and foundation founder Lynn Schusterman (right) at the Israel Institute’s 2016 leadership summit, held in Israel.

Dov Waxman, a political scientist who directs the Israel studies center at UCLA and serves on the Israel Institute’s advisory board, said the organization doesn’t determine the material taught by visiting Israeli scholars in his department: “They just want to make sure these courses are popular, but they don’t seem to have any involvement with the actual content.” Waxman typically chooses which scholars to invite to his program before having them apply to the institute for approval. Roth, the institute’s executive director, said the organization does not ask about scholars’ political perspectives in the application process. But the hiring process at UF suggests that in some cases, the Israel Institute attempts to have some influence over which scholars are selected to receive its funds.

For an example of what donors can accomplish in Israel studies, advocates often point to the program at the University of California, Berkeley—a symbolically important campus given its history of left-wing student activism—which Bard calls one of his “proudest achievements.” In 2003, the Helen Diller Family Foundation—a California Jewish foundation known to have funded the controversial Canary Mission blacklist of Palestine activists—established a visiting Israeli professorship in the Middle East studies department at the university; Diller said in interviews that the position was created in response to “the protesting and this and that.” Right-wing Zionist commentators were outraged when a faculty committee selected the geographer Oren Yiftachel, an incisive critic of Israel, as the first Diller Visiting Professor, but Israel advocates didn’t give up on placing sympathetic scholars on campus. In 2008, AICE brought Hanan Alexander, an educational philosophy professor who had grown up in Berkeley and later moved to Israel, to the university as a visiting fellow. Alexander told me that upon his arrival, he found the campus dominated by the voices of Israel critics and in need of more “balance.” During his fellowship, he helped organize an academic conference—the theme was “Israel as a Jewish and Democratic State: Challenges and Perspectives”—and involved himself in campus politics, speaking out against a BDS resolution and personally lobbying students to vote against it.

Alexander’s work helped inspire a law school professor named Kenneth Bamberger, an expert in technology and corporate compliance, to push for a permanent Israel studies program. According to Alexander, the law school turned out to be an ideal home for this project: The school had a “supportive dean,” and Israel-related efforts were usually less controversial there than in the humanities and social sciences. In 2011, thanks to Bamberger’s advocacy and fundraising, the Berkeley Institute for Jewish Law and Israel Studies launched with a grant from the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Foundation, a major funder of Jewish and “pro-Israel” projects. (In 2021, the institute was renamed for Diller after her foundation provided an $11 million endowment.) The institute hosts visiting Israeli scholars and awards fellowships to undergraduate students to create their own courses or host events; a glowing 2016 profile in the Jewish News of Northern California featured a student who had taught a class on “Israeli high-tech innovation.”

In 2019, when Diller donated $5 million to endow another chair in Israel studies at Berkeley—this time in the Israel studies institute and not the Middle East studies department—the university made an internal hire, selecting the institute’s co-director, Ron Hassner. An outspoken critic of Palestine solidarity activism on campus, Hassner frequently lambasts BDS in letters and op-eds in the press, including in the student newspaper. Students involved in Israel advocacy on campus see the institute as a resource. “We relied on [the institute] as a source of credibility,” said Lily Greenberg Call, a 2019 Berkeley graduate who served as the president of the campus AIPAC affiliate, Bears for Israel, and has since written in Teen Vogue about rejecting AIPAC’s influence on American politics. “A lot of the argument we would use to counter BDS was that you shouldn’t boycott academics and cultural things. Having an event with a professor was more credible—we tried to do a lot of events with them.”

“We relied on the Israel Institute as a source of credibility. Having an event with a professor was more credible—we tried to do a lot of events with them.”

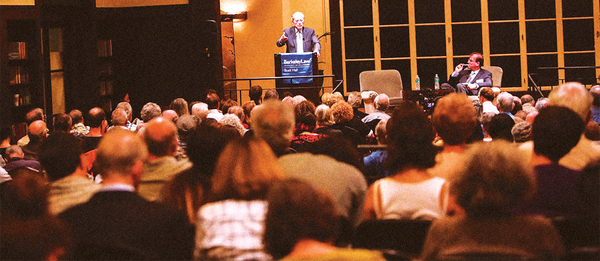

Itamar Rabinovich, a former Israeli ambassador to the US and the founding president of the Israel Institute, addresses a crowd at UC Berkeley during a 2015 event with the school’s Institute for Jewish Law and Israel Studies.

Universities have long been a favorite avenue for giving among wealthy donors: According to a 2019 report by the research firm the TIAA institute, in 2017, nearly half of all donations from the 50 wealthiest US philanthropists went to institutions of higher education. As public funding for education has decreased and income concentration among the one percent has intensified, big donations have become a larger share of university budgets. Gifts from private foundations now make up roughly one-third of all giving to universities, up from one-fifth in the early 1990s. University administrators are under pressure to keep up with their competitors’ ballooning endowments: “It’s an arms race mentality, and that doesn’t lend itself to a deliberate and circumspect process about which offerings of funding should be accepted or rejected,” said Ben Soskis, a senior research associate in the Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy at the Urban Institute. In this environment, philanthropists have seen new opportunities to exert influence: The Koch brothers, for example, became notorious for giving tens of millions of dollars annually to hundreds of American universities with the intent of bolstering the study of free-market economics.

Area studies programs—the interdisciplinary fields that focus on particular geographic areas—have a distinctive history of reliance on politically motivated funding. They emerged in the context of the Cold War, nurtured by government and foundation funders who hoped to increase US influence around the world. In recent decades, foreign governments—from the Saudi government to the Turkish one—have poured billions into US universities, ostensibly to improve their countries’ images. “The Turkish government put money into chairs at Princeton and other universities, and the people in those chairs didn’t say much about the Armenian Genocide,” said Lockman.

As giving has skyrocketed, however, donors and their beneficiaries have come under new scrutiny from students, faculty, and the public—including in the field of Israel studies. This year, the University of Chicago chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) called for a boycott of classes taught by Israel Institute fellows, arguing that regardless of any visiting professor’s personal politics, the institute itself should be censured due to the Schusterman Foundation’s history of funding Israel advocacy, and some staff members’ ties to the Israeli security state via organizations like the Tel Aviv Institute for National Security Studies. At Berkeley, the law school’s SJP chapter unsuccessfully lobbied the university last year to reject the donation from the Diller Foundation for the Israel studies institute.

Where it was once accepted that major donors would have some influence over how their gifts were spent, student and faculty advocates have not only demanded an end to personalized gift agreements, but have argued that universities should be required to make all such agreements public. “Universities typically cite the confidentiality of the donor as a reason not to share details of what has been agreed,” said Charles Keidan, executive editor of Alliance Magazine, which publishes reporting and commentary on philanthropy. “But universities are public institutions with charitable status. I think there’s a legitimate public interest in having more transparency around these agreements, even if that means certain money is not received.” When donors do overreach, faculty often cling fiercely to their independence. In area studies departments funded by foreign states, a gift has proved to be no guarantee that an academic will adopt the party line. “Most of the people in American Middle East studies are critical of reactionary regimes in the region,” Lockman said. “They’re not going to start saying nice things about the Saudi Arabian king just because he gave money for a chair.” Israel studies is no exception, as Bard readily admits: “It’s kind of a crapshoot for funders of Israel studies, because there are so many Israel studies professors out there who are hypercritical of Israel and in some cases, even anti-Israel,” he said.

Many scholars are not so much drawn to Israel studies as turned away from other departments in the humanities and social sciences due to the lack of tenure-track openings.

Many such scholars were not so much drawn to Israel studies as turned away from other departments in the humanities and social sciences due to the lack of tenure-track openings. “Scholars are finishing PhDs from the best universities in the world, and there are no jobs,” said Arie Dubnov, a historian who holds an Israel studies chair at George Washington University. Israel studies, by comparison, is flush with resources. Halperin, for example, received the $15,000 AICE Israel studies grant four years in a row as a graduate student, which she described as “incredibly helpful” in supporting her dissertation research—though she remained “continually uncomfortable” with the presumption expressed at AICE conferences that she would play a role in Israel advocacy. When she entered the post-recession academic job market during the 2010–2011 school year, she applied to three open Israel studies positions and was a finalist for each.

Despite her alienating experience with AICE, Halperin quickly realized that she wasn’t an outsider among her colleagues in Israel studies. “I wasn’t alone in feeling uncomfortable with the presumption that everyone there was disgusted with Middle East studies,” she said. Rashid Khalidi, a historian of Palestine and the modern Middle East at Columbia University, observed, “Most of the best scholarship on Israel nowadays is out of tune with the mainstream, mendacious hasbara narrative.” (Hasbara, meaning “explanation,” is a term for Israeli propaganda.) “It’s a real problem for donors who want somebody to spout the Israeli government line to find respectable scholars who will do that.”

In March, the Middle East Studies Association (MESA), with which AIS has been affiliated since its founding, voted 786–168 to endorse the BDS movement. AIS members were the only scholars to speak out against the proposal at the MESA board meeting where it came up for debate, according to Lustick, who supported the resolution. In a statement, AIS president Arieh Saposnik argued that the vote “casts a net of collective and inescapable guilt over any citizen of Israel” and amounts to “collective punishment” of Israeli scholars. The actual wording of the resolution specifies that MESA’s intent is to target institutions, not individuals, meaning that Israeli scholars’ personal memberships will not be in jeopardy; MESA has also clarified that neither individual members nor affiliate organizations like AIS are required to practice BDS. Still, at the association’s annual conference in June, the AIS membership voted 36–11 to approve the board’s motion to officially disaffiliate from MESA; only a small number of the association’s 590 members actually voted.

Israel studies scholars attend the General Assembly at the Association for Israel Studies’s June 2022 annual conference, where they voted on whether the association should disaffiliate from the Middle East Studies Association in response to its vote to adhere to the BDS movement.

The controversy over the BDS vote is illustrative of conflicting visions for the future of Israel studies: Does the study of Israel require fidelity to the politics of the Jewish state, or can the field encompass scholarship—and scholarly activism—that challenges those ideological commitments? This simmering conflict is only intensified by changes to the composition of AIS’s own membership, driven in part by donors and advocates who see the field as a vehicle for “pro-Israel” politics. Sorek notes that the professors who hold donor-funded chairs often have outsized influence in the association: “Those positions come with the power to organize conferences, to invite people,” he said. Though some of these chairs are held by more critical scholars like Halperin and Dubnov—and in recent years Dubnov, Halperin, and Sorek have won AIS’s biggest prizes—a substantial group hold views more in line with their donors’. “When we started AIS, we thought of it as a political resource for scholars who needed a place where they could work on Israel without being constrained by Israeli government policies or Saudi money,” said Lustick. “It’s not surprising that when the organization became successful—and Israel started to feel the pressure of international criticism throughout academia—AIS [became] a vehicle for something it wasn’t created to be.” The organization has developed close relationships with advocacy groups and politicians: As recently as 2016, its annual conference, held that year in Jerusalem, was put on with support from Keren Kayemet LeYisrael (KKL-JNF), Israel’s Jewish National Fund, which has historically been responsible for controlling much of the state’s land and settlement. In 2019, the conference featured a keynote speech by Hanan Melcer, deputy president of Israel’s Supreme Court. At multiple conferences, roundtables about topics like Israel on campus and definitions of antisemitism have included panelists from Israel-advocacy organizations like Americans for Peace and Tolerance and the Foundation to Combat Antisemitism.

Several scholars told me that the split within AIS is often generational, pitting an “old guard” more comfortable with Israel advocacy against younger scholars, who, in Wallach’s words, “have no problem with the framework of settler colonialism or critical approaches to Zionism. Even if they don’t necessarily agree, they’re not horrified.” These fissures deepened in 2019 when AIS’s affiliated journal, Israel Studies, published a special issue with the theme “Word Crimes,” which contained a collection of essays arguing that various terms—including “apartheid,” “colonialism,” and “occupation”—were misapplied in the context of Israel/Palestine. In response, nearly 200 professors and grad students signed a letter lambasting the journal, arguing that the issue’s contributors lacked academic expertise and “made minimal and inadequate reference to relevant scholarship.” “The problem with the issue was that it declared categories like settler colonialism to be beyond the boundaries of legitimate academic discourse,” said Wallach, who spearheaded the letter. Dubnov, who had been selected to receive that year’s AIS “Young Scholar Award” (which was jointly conferred by the Israel Institute), declined the prize in protest and officially ended his AIS membership, as did Shafir and Sorek; 11 members of the Israel Studies editorial board resigned, saying they had been unaware of the issue before its publication. Ultimately, co-editor Ilan Troen and Natan Aridan publicly apologized, though then-AIS president Donna Robinson Divine, who served as a guest editor for the issue, told me she stands by their work.

Leena Dallasheh, a professor at Cal Poly Humboldt

The split within AIS is often generational, pitting an “old guard” more comfortable with Israel advocacy against younger scholars.

Halperin’s fallout with Benaroya became another flashpoint for disagreement in the field. Several scholars described being frustrated with AIS president Saposnik’s statement on the matter, which called the incident “unfortunate” but avoided wholeheartedly backing Halperin, describing the return of the endowment as “subject to various interpretations.” In an interview with me, Saposnik said that while academic freedom is a priority for AIS, the UW case also involved tensions over “the integrity of Israel Studies as a field,” since Halperin had been describing her courses as Israel/Palestine studies. “We do believe that donors who donate to a particular program have a right to have that program,” he said. “That doesn’t mean they can expect that the position will turn into an advocacy position by any means. But somebody who donated to a French studies program wouldn’t expect it to become an American studies program instead.”

Indeed, the conflict over the direction of Israel studies is partially a debate about where to draw the boundaries of the field. Should Israel studies encompass the years preceding the foundation of the modern State of Israel—or should pre-1948 study be considered Palestine studies? Since Israel currently maintains control of the West Bank and de facto control of Gaza, should Israel studies include scholarship on the Palestinian territories? Since the mid-1990s, some scholars have called for a “relational approach” that understands Israeli and Palestinian history as so deeply shaped by each other as to be inextricable for the purposes of study. In recent years, that view has gained traction in the field. “If you look at the reality today, we cannot separate Palestine and Israel,” Sorek said. “There is one system of control. That’s the reality, and scholarship is about facing reality.”

Scholars with a range of political persuasions continue to see a benefit in studying Israel and Palestine separately. “It would be difficult to study the history of France without studying the history of Germany. But that doesn’t mean that every French studies program has to become a French German studies program,” Saposnik said. Some Palestinian scholars, meanwhile, worry about the implications of allowing their field to be subsumed by Israel studies, given its location in Jewish studies departments and its entangled relationship with Israel advocacy. “Israel studies tends to be mainly focused on Jewish citizens of Israel,” said Khalidi. “I’m not sure there’s much place for the study of Palestine.” Khalidi and other scholars have developed the field of Palestine studies, but currently make do with paltry resources compared to those available for Israel studies: In the US, apart from Khalidi’s small academic center for Palestine at Columbia University, there is just one endowed chair in Palestine studies, held by Beshara Doumani at Brown University. Meanwhile, Israel studies positions are almost always filled by Jews. “There are almost no Palestinians in any of these Israel studies programs as far as I can tell, which gives you a sense of something structurally that’s not working,” said Leena Dallasheh, a Palestinian citizen of Israel and history professor at Cal Poly Humboldt who has unsuccessfully applied for Israel studies jobs in the past. “It was built as an exclusionary space—a space that wasn’t supposed to have people like me.”

A pro-Israel student group at New York University invites passersby to participate in an installation for Israel Pride Week in 2017.

Even as some scholars work to make room in the field for critical perspectives on Israel, Israel-advocacy groups have grown more adept at defending donors’ ability to get what they paid for.

Still, Dallasheh, who has also struggled to find a home for her work in Middle East studies, said she thinks that Palestinian scholars would be open to joining programs in Israel/Palestine studies if the field first disentangled itself from Zionist advocacy. “[Once] a critical generation of scholars grows and becomes the more prominent part of AIS, that’s what’s going to happen,” she predicted. In recent years, faculty positions in Israel/Palestine studies have been established at the University of Colorado and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Lustick has advocated for eventually replacing AIS with an Israel/Palestine studies association. But the vote to disaffiliate from MESA indicates that the association is moving away from that vision. “Disaffiliating [from MESA] would be to cut off our nose to spite our face,” Lustick wrote in a letter to fellow AIS members before the final vote. “The scouring attention devoted to Palestinian issues in MESA is as relevant for AIS members as is understanding Zionism, Israeli Jews, and Israeli institutions, for the majority of MESA members.”

Even as some scholars work to make room in the field for more critical perspectives on Israel, Israel-advocacy groups have grown more adept at defending donors’ ability to get what they paid for. StandWithUs, the “pro-Israel” campus group that supported Benaroya in her complaint against UW, works with donors to negotiate gift agreements to include specific conditions, as its legal director Yael Lerman explained in a November 2021 article written with legal consultant Jonathan Rotter for the right-wing Jewish news site The Algemeiner. Among other things, they suggest adding clauses that prohibit professors from promoting BDS and require them to adhere to the controversial IHRA definition of antisemitism, which has been criticized for limiting legitimate political speech by defining certain censure of Israel as antisemitism. StandWithUs also suggests that donors should structure endowments to pay out gradually over time, making it easier to cut off an offending beneficiary.

These efforts by donors to exert control have far-reaching implications for the field of Israel studies. In a March essay for the Chronicle of Higher Education about the UW controversy, Lila Corwin Berman, a historian at Temple University who studies the history of American Jewish philanthropy, described efforts to restrict the uses of gifts as “a bid for hard power to punish scholars and restrict knowledge,” and ultimately to “discipline and control free inquiry at universities.” Donor advocates say the alternative to accepting donors’ terms may be to do without their funds, which have made Israel studies attractive to some of its most respected scholars in the first place. Bard, for his part, continues to encourage donors to give, with strings attached. “Unless the universities don’t want any money, I’m not sure how you get around the fact that donors have expectations,” he said. “You don’t get to simply say, ‘Give me money so that I can do whatever I want.’

Support for this article was provided by a grant from The Puffin Foundation.

A previous version of this article said that Middle East studies departments were originally funded by the federal government. In fact, some Middle East studies centers receive federal funding, but academic departments do not.

Mari Cohen is associate editor at Jewish Currents.