The Energetic Executive

Ron DeSantis wants to make his blueprint for Florida—outlined in the rancorous memoir written for his failed presidential campaign—into a model for the rest of the country.

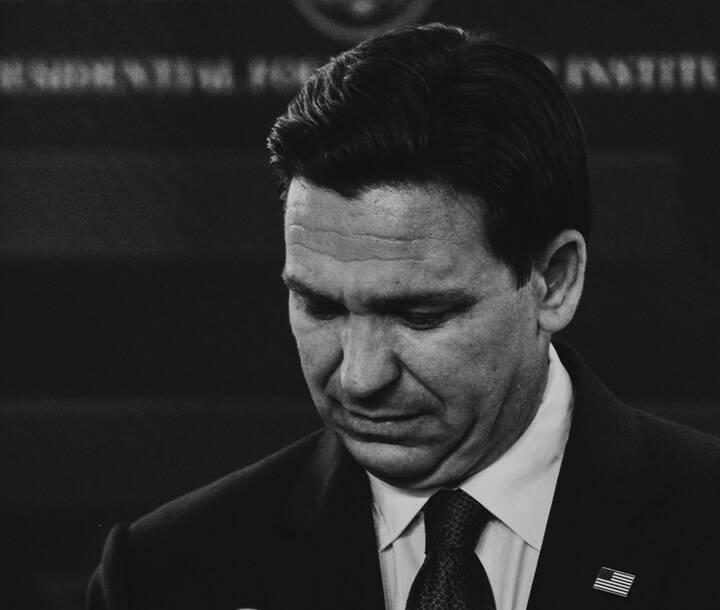

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis

Discussed in this essay: The Courage to Be Free: Florida’s Blueprint for America’s Revival, by Ron DeSantis. Broadside Books, 2023. 288 pages.

In 2011, before his first congressional campaign, Ron DeSantis was just another debut author in search of readers. For months, he traveled across his home state of Florida to Tea Party meetings to hawk Dreams From Our Founding Fathers, his diagnosis of America’s ills and missteps under the leadership of Barack Obama, issued by a local vanity press known mostly for schlocky genre fiction. As the title suggests, the book was meant as a smug rejoinder to Obama’s 1995 memoir; in practice, it was a fairly straightforward recitation of Tea Party talking points, enlivened only by the occasional, feeble potshot at Obama’s personality and background. DeSantis thus revealed himself to be one of those special souls who, after surveying the world and finding it wanting, decides to self-publish a book. Among the many strains of narcissist in existence, this one is among the most deranged—perhaps outmatched only by those egomaniacs who believe that they should be president.

DeSantis, it turns out, qualifies as both. Twelve years and several terms in the House and the Florida governor’s mansion later, he barreled headlong into what veteran GOP strategists have called the “Worst Republican Presidential Campaign Ever.” He ran as “Trump without the baggage,” to the praise of establishment Republicans; some of his volunteers knocked doors and distributed cards that read “DeSantis Solves Problems . . . With No Drama.” But what DeSantis failed to recognize was that enthusiastic Trump voters like the drama and the baggage. To the former president’s supporters, his verbal volatility, unpredictable behavior, and indifference to political norms are not drawbacks, but signs of strength. DeSantis saw the voters he was determined to steal the same way the mega-donors who fed his campaign did: as feeble-minded people who, deep down, wanted to follow a responsible authority figure. He promised them efficiency in manipulating a system that they hoped to see completely destroyed. Trump had found a base that wanted an outlaw; DeSantis offered them an administrator in cowboy boots.

But before DeSantis suspended his presidential bid in January; before his campaign found itself running on fumes, hemorrhaging donors, and polling in the single digits; before he even officially declared his candidacy, he published his second book, this time with a real-deal press. His campaign memoir, The Courage to Be Free: Florida’s Blueprint for America’s Revival (2023), was his pitch deck to the voters who did not ultimately support him and the donor class who did—at least until his stock plummeted. Like all works in its genre, it naturally repels any search for greater insight into its subject’s essential nature. But as the blueprint that it promises to be, it is ruthlessly competent. While DeSantis may have become synonymous with embarrassing hubris, the vision Courage maps out—tediously, yes, and with the same charmlessness and lack of subtlety that cost its author his national reputation—is a coherent and alarming one. The failure of a single vehicle for its expression isn’t enough to kill it off.

Indeed, DeSantis’s flop may have limited his sphere of influence to Florida, but Courage goes to great pains to emphasize that his home state—which he calls “a beachhead of sanity”—could be a prototype for the rest of the country. “Florida has stood as an antidote to America’s failed ruling class,” he writes. “Policies in Florida empower individuals to make the most of their own lives, including by limiting the power and influence of large, politically connected institutions that operate in accordance with leftist ideology.” For DeSantis, of course, “empowering individuals” means undercutting the workings of democracy to increase the influence of his supporters and allies, and “limiting the power of institutions” amounts to attacking any people or body that would undermine this goal. And, just as Courage suggests, the ultra-reactionary laws that have accomplished these aims in Florida have often prompted copycat bills across the country. The state has also become a welcome environment for the national chapters of far-right groups like Moms for Liberty and a breeding ground for white nationalists; the anti-democracy Claremont Institute launched its newest office in Tallahassee last February, a month after DeSantis set in motion the right-wing takeover of New College of Florida, a small public liberal arts college once known as a bastion of progressivism and a haven for queer students. All of this remains relevant to the lives of Floridians even after DeSantis was laughed out of the presidential race, and it threatens to become increasingly relevant to the lives of other Americans, too. As DeSantis put it when he suspended his campaign, “The mission continues. Down here in Florida, we will continue to show the country how to lead.” Reading Courage now—on the precipice of a likely second Trump term, which analysts warn promises to be more ideologically organized than the first—one is inclined to take the threat seriously.

Courage casts DeSantis as the kind of down home “regular guy” that is ubiquitous in American politics—a kind of guy that he clearly is not.

As with any marketing ploy, Courage sells a brand, casting DeSantis as the kind of down home “regular guy” that is ubiquitous in American politics—a kind of guy that he clearly is not. Early in the book, we are told that while DeSantis was “geographically raised in Tampa Bay,” his “upbringing reflected the working-class communities in western Pennsylvania and northeast Ohio” where his parents were from. To anyone familiar with Pinellas County, where DeSantis grew up, this is laughable. It’s the same county, as it happens, where my parents—Philadelphia transplants—raised my brother and me, and it’s the kind of manicured and sheltered suburban community that gets parodied in movies like Edward Scissorhands (which was filmed in nearby Lutz). During DeSantis’s childhood, the area was becoming inundated with high-tech manufacturing companies and financial firms. His father worked for Nielsen Media Research, whose local headquarters were in his hometown of Dunedin; his mother was a nurse. Though he wasn’t raised with outsized wealth, he grew up in the kind of insulated and atomizing place that encourages intolerance, even contempt, for anything that doesn’t fit its mold.

From Florida, where he played competitive youth baseball, DeSantis was recruited to play at Yale. It’s at this point, in a memoir relatively light on biographical detail, that the reader receives an uncomfortable glimpse into the governor’s villain origin story. Stepping onto campus, he tells us, triggered in him a disturbing “culture shock.” “Here I was, a blue-collar kid from Tampa Bay,” he writes, “at a university in which a large percentage of students were from families who were millionaires.” But the hostility he describes—the same hostility that animates Courage and, it seems, his political career—reads less like an awakening to injustice than the resentment of the petit bourgeois. “I assumed doing well at a place like Yale would allow me to move up in what Lincoln called the ‘race of life,’ to advance in America’s meritocracy,” he writes. Instead, he claims to have been stunned by his peers’ “unbridled leftism” and their “wholesale rejection of the basic principles that constituted the foundation of the American experiment: the Judeo-Christian tradition, the existence of Creator-endowed rights, the notion of American exceptionalism.” In other words, rather than feeling welcomed into the fold, swept inevitably into the tide of prestige and opportunity that such an institution had always offered men like him, DeSantis felt rejected.

DeSantis’s many attempts to paint himself as blue-collar—and his tendency to equate having parents from the Rust Belt with having a working-class upbringing—are representative of a discrepancy at the core of the memoir. While DeSantis claims to address the disaffected working class, the pose he strikes in Courage does not seem directed at these voters at all. Instead, it’s perfectly calibrated to validate the assumptions of the wealthy conservatives who he hoped would smooth his path to power: the ones invested in seeing class as a set of values, beliefs, and superficial signifiers rather than a life-shaping relationship to capital. In fact, DeSantis states explicitly that he considers a person to be a member of the elite not by virtue of power or wealth, but rather by “shar[ing] the ideology and outlook of the ruling class,” offering Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas as an absurd example of someone who is not an elite “because he rejects the group’s ideology, tastes, and attitudes.” Under this worldview, an adjunct professor is not working-class, but a self-employed electrical contractor with a six-figure salary is. It is the same worldview in which there’s no contradiction between bragging, “In Florida, we beat the elites” and erasing local living-wage requirements, or loosening regulations on child labor laws and heat-exposure protections that keep workers safe.

Those acts of craven deregulation were foreshadowed by DeSantis’s early career in the military. After graduating from Yale and Harvard Law School, he joined the Navy as a prosecutor, prompted, he writes, by his sense that he had an “obligation to serve” his country after 9/11. After a stint as a legal adviser at the infamous Guantánamo Bay detention camp, where he counseled officers that they could force-feed prisoners on hunger strike, he was deployed to Iraq in 2007 as an adviser to the commander of the Special Operations Task Force-West in Fallujah. In this position, he provided legal justifications for reducing the red tape that he felt was forcing every American soldier to operate “with one hand tied behind his back.” (DeSantis writes of the “very low” likelihood that “Navy SEALs—who are perhaps the best-trained war fighters in the world—would intentionally flout the laws of war,” an almost comically obtuse thing to say about a unit that whistleblowers have called “lawless” and described as operating as if they were “untouchable,” and that shielded people like Eddie Gallagher, who was accused of fatally stabbing a detainee in 2017.) “My job is to help you accomplish your mission,” he explained to his commander. “Not to impede it.”

Back home in Florida, DeSantis ran for Congress in 2012—a race he recounts, of course, as an underdog story: “I . . . had virtually no name recognition . . . and I did not have any money or rich friends to support me.” In reality, DeSantis, equipped with his Ivy League connections, raised more than all of his opponents combined; he used the money on massive ad buys attacking the other Republican primary candidates with false claims and distortions. He won by a landslide. Notably, during his time in Congress, DeSantis was not yet trying to cultivate the image of the brutally effective change agent that he would later make his imprimatur. Colleagues described him as “a backbencher” who was “not a very effective member of Congress,” and who, per Politico, “was probably best known . . . for being a standout on Republicans’ congressional baseball squad.” He was a founding member of the hard-right House Freedom Caucus but “had a way of ‘dipping out and disappearing’ from meetings if a leadership fight or funding battle was not playing well,” as another senior member told The New York Times. In Courage, the only successful piece of legislation he takes ownership of, after six years in the House, is something called the Puppies Assisting Wounded Servicemembers for Veterans Therapy Act, or PAWS, which paired veterans with service dogs, and which only passed after he left office. DeSantis blames his disappointing tenure on the dysfunction of Congress itself, which he disparages as beholden to a bureaucratic “expert” class that he calls “a federal apparatus that exists outside the confines of constitutional accountability and draws almost entirely from the coastal, college-educated, self-appointed elite.” He saw himself as fit to exercise greater power than he could garner as just one in a sea of representatives. “I felt that I had the capacity to provide good service,” he writes in Courage, “but only if the position afforded me the opportunity to exercise leadership.”

DeSantis’s disdain for Congress—though arguably warranted by the body’s gridlocked absurdity—hints at his more thoroughgoing skepticism of democracy itself. This suspicion shows up early in Courage, during his time in Iraq, where he became convinced that US intervention had gone against the principles of the Founding Fathers. “The Founders would not have thought of forcibly removing a dictator and then having a society governed by the mere whims of the majority as ‘liberty,’” he writes. “They knew that liberty could be squelched by a runaway majority just as easily as it could be by a single tyrant.” Indeed, upon narrowly winning his race for governor in 2018, DeSantis quickly proved to be untroubled by tyranny as long as the tyrant in question was him. At last, he writes, he “was not just one of many elected to a legislative body, but was the one man elected to lead a state of more than twenty million people”—a line revealing a taste for executive dominance that he acted on almost immediately.

In the grand Republican tradition of shrouding policy goals in deceptively inoffensive language, DeSantis calls his autocratic approach being an “active governor.”

Ron DeSantis during a news conference in Miami Beach, March 2024.

In his first days as governor, DeSantis asked his transition team to compile “an exhaustive list of all the constitutional, statutory, and customary powers of the governor,” which he pored over, seeking “every lever available to advance our priorities.” What all of these priorities had in common was that they allowed DeSantis to parlay panic and fear, both real and manufactured, into greater executive power. He claimed that undocumented immigrants were bringing violent crime and drug trafficking, and that he needed to reestablish and expand the Florida State Guard—a World War II-era civilian volunteer force that reports directly to the governor—to “protect [Florida’s] people and borders from illegal aliens and civil unrest”; The Miami Herald referred to the guard as “DeSantis’ own militia.” Playing off fears that children in Florida were being “indoctrinated,” DeSantis proposed, then signed into law, the Stop WOKE Act, which prohibits public schools from teaching critical race theory—effectively permitting him to shape statewide curricula. Despite his vow to “bring the administrative state to heel,” he leveraged widespread fear of voter fraud and election manipulation to create a first-of-its-kind state agency, the Office of Election Crimes and Security, which reports to the governor-appointed secretary of state and has the power to prosecute alleged voter fraud. (The office has already ordered the arrests of 20 people, at least half of whom thought they were eligible to vote after the statewide approval of Amendment 4, which restored voting rights to Floridians with felony convictions.) In 2020, DeSantis also used the ubiquitous panic caused by the Covid-19 pandemic to enact an even more unequivocal vision of executive authority, arrogating to himself the power to direct the spending of the billions the state received in federal aid without seeking legislative approval. In the grand Republican tradition of shrouding policy goals in deceptively inoffensive language, he calls this autocratic approach being an “active governor.”

The best example of what DeSantis calls his use of “executive energy” is his aggressive takeover of the Florida legal system. In his first weeks in office, he appointed three Federalist Society-vetted conservative justices to the state Supreme Court, long known as a liberal-leaning body. His selections have paid off—consistently ruling in his favor, including on abortion and capital punishment. When the state was being redistricted in 2022, DeSantis made the unprecedented move of throwing out state lawmakers’ proposed congressional map and putting forward one of his own devising, which drastically decreased Black Floridians’ voting power; the governor forced the plan through the legislature, and the First District Court of Appeals later let it stand. (A circuit judge recently ruled that the map is unconstitutional.) That same year, DeSantis suspended and then removed elected State Attorney Andrew Warren from office for signing a statement committing to refrain from prosecuting abortion cases after the overturning of Roe v. Wade. A federal judge ruled that the removal violated the state constitution, but the state Supreme Court upheld DeSantis’s decision.

By the time Courage came out in February 2023, DeSantis had Florida well in hand. That November, he had won his second term in an unprecedented landslide, and in the months leading up to the election and directly afterward, he had secured a series of legislative victories: the six-week abortion ban, the Stop WOKE Act, the concealed carry law, the sweeping immigration law. Many of his big-ticket acts not only passed through the state legislature that he has brought more and more under his own control—not least through the district map that his office drew, which effectively gives Republicans a 20–8 edge—but were also upheld by the state Supreme Court that he has decisively remade in his favor. For the cherry on top, in January 2023, DeSantis appointed a conservative majority to New College’s Board of Trustees. The new board fired the president; dismantled the diversity, equity, and inclusion office; and, taking a page from Hungary’s authoritarian prime minister Viktor Orbán, abolished the college’s gender studies major. DeSantis’s Florida is becoming a self-perpetuating machine—one where there are fewer and fewer dissenting voices to get in the way of implementing his blueprint. All this has even changed the state’s population. Professors across the state are leaving even tenured positions; young people and others who cannot afford the skyrocketing rent and untenable insurance prices are joining the exodus. Conservatives, meanwhile, are traveling the opposite route. “There are folks who largely feel unrepresented by GOP leaders in DC and have gravitated to Florida largely because we have led with an agenda that represents the values of people like them,” DeSantis writes. People are fleeing to Florida, he boasts, because it is “a citadel of freedom in a world gone mad.”

Failure has not humbled Ron DeSantis. Since face-planting on the national stage, he has only doubled down on his role as an energetic executive, ready to whip up panic and paranoia anew. In March, he signed a measure that increased jail and prison sentences for undocumented immigrants convicted of driving without a license. In April, he signed another that will add lessons on “the truth about the evils of Communism” to public school curricula as early as kindergarten. Also this spring, he sent 250 state and National Guard members to the southern coast to “combat illegal vessels coming to Florida from countries such as Haiti,” saying in a statement that “when a state faces the possibility of invasion, it has the right and duty to defend its territory and people.” With more than two years left to govern until his term expires in 2027, he has plenty of time to wreak further havoc while he plots his next moves. And it seems nearly certain that he will run for president again. If there is anything else to be gleaned from The Courage to Be Free, it is that its author views himself less as the bully he is often described as than someone who was bullied himself, and that he is desperate to prove his doubters wrong.

As DeSantis continues to refine his formula for a Caesarist Florida, a state where a leader can act unchecked while still superficially working within a democracy, the national GOP can track the outcome of his increasingly authoritarian policies—and put its weight behind whatever it judges will stick outside the testing ground of the Sunshine State. Indeed, if you remove DeSantis’s unappealing person from his despotic blueprint, you get something that looks a lot like Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s outline for a second Trump presidency. It proposes, among other things, to make thousands of civil servants fireable at-will, initiate legal action against progressive prosecutors in order to flush out a “rogue” movement, strip certain federal benefits from noncitizens, abolish federal DEI policies—and various other precise, wonky interventions that exacerbate inequality and allocate more and more power to the executive while immobilizing any institutional roadblocks to unilateral power, including the other branches of government. DeSantis may have tried and failed to run as Trump, but he infused the Trump campaign—or, at least, its broad orbit of wonks and advisers—with some DeSantis-like qualities in the process. The former president’s appropriation of elements of the Florida governor’s platform suggests that the powerful people DeSantis courted in Courage heard his pitch and liked it. They just went with a more qualified candidate.

Samantha Schuyler is a writer from Florida living in New York City.