Survivor’s Guilt

In his Novi Sad trilogy of post-Holocaust fictions, the Serbian novelist Aleksandar Tišma examines the psychologically warping effects of antisemitism.

Discussed in this essay: The Use of Man, by Aleksandar Tišma, translated by Bernard Johnson. NYRB Classics, 2014. 368 pages.

The Book of Blam, by Aleksandar Tišma, translated by Michael Henry Heim. NYRB Classics, 2016. 248 pages.

Kapo, by Aleksandar Tišma, translated by Richard Williams. NYRB Classics, 2021. 312 pages.

In Zagreb, Yugoslavia, a few decades after the close of the Second World War, retired railroad engineer Vilko Lamian is having lunch at a café when he notices a man whom he suspects may be a Jew. It’s not the man’s “broad, prominent nose,” “thick lips,” or “diffident, withdrawn chin,” but something in his bearing: his clumsiness, weakness, and air of itinerancy, “the sign of otherness . . . which [Lamian] had always seen as Jewish.” Despite the tone of this observation, Lamian is not an ordinary unrepentant fascist biding his time in a fragile socialist state. He is, in fact, a Jew himself, from the Croatian city of Bjelovar, and a survivor twice over: first imprisoned at Jasenovac, a concentration camp built by the Croatian ultranationalists of the Ustaše, he was eventually transported to Auschwitz. But unlike most of his fellow prisoners, Lamian was not only on the receiving end of genocidal violence. He also inflicted it.

Lamian, the central character of a 1987 novel by the Serbian writer Aleksandar Tišma, is a former kapo, a member of the class of camp inmates that helped enforce the will of SS guards in return for preferential treatment. This term, which lives on today as an epithet deployed amid intracommunal Jewish conflict, serves as the title for the final entry in Tišma’s Novi Sad trilogy of post-Holocaust fictions, originally published in the 1970s and ’80s and reissued by NYRB Classics over the last seven years. Set in and around the ethnically diverse Serbian city of Novi Sad at various points before and after the war, The Book of Blam, The Use of Man, and Kapo eschew tidy narratives about sanctified victims, devoting themselves instead to grim studies of survivor’s guilt, the psychologically warping effects of antisemitism, and the burden of memory in a society that would rather forget.

These were themes of great personal significance to Tišma, whose mother was a Hungarian Jew and who escaped persecution only by fleeing to Budapest in 1942, at the age of 18, a year after Novi Sad fell to a combination of German and Hungarian troops; Jews in the Hungarian capital were at that point better protected than those living under occupation, and as a student, Tišma enjoyed special privileges. Many of Tišma’s Jewish characters come from mixed religious households like his own, but few are as fortunate as he was: Only The Book of Blam’s protagonist manages to avoid the camps, thanks to his marriage to a Christian woman. The Novi Sad novels can feel at times like acts of imaginative atonement for Tišma’s own good luck.

The Book of Blam, The Use of Man, and Kapo eschew tidy narratives about sanctified victims.

Stylistically, the trilogy is marked by the relatively long period over which it was composed. The Book of Blam (1972) depicts a few days in the postwar life of Miroslav Blam as he is pursued by figures from his past, both real and imagined. Here Tišma takes a collagist approach, mixing chapters of literary realism with hallucinatory passages of dialogue, one-sided correspondence, and snatches of the collaborationist newspaper Naše novine. The trilogy’s centerpiece, The Use of Man (1976), retains these magpie instincts—it features a peripheral character’s diary printed in its entirety—even as it broadens the frame to examine the interconnected lives of a Jewish teenager named Vera Kroner and two of her male classmates. Kapo, the series’ last and most compelling installment, represents a radical formal contraction: The narration closes in on a single, hysterical consciousness as Lamian sets off on a quest to track down Helena Lifka, a woman he abused in Auschwitz and who, he is shocked to realize, is not Hungarian as he long assumed, but a Yugoslav Jew like himself. Even as Tišma experimented with various methods of rendering wartime devastation, his fiction never wavered in its profound pessimism about what it means to be a Jew—or in its certainty that genocidal violence is bound to repeat itself.

In the early years of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, international travel was strictly regulated, and it took Tišma many years of trying before he was able to obtain a passport. When he was eventually granted one in 1955, he began writing the travelogues that, alongside novels, story collections, poetry, plays, and literary reviews, would come to form his oeuvre. In 1963, he published Meridians of Central Europe, in which he describes a trip to Poland he took two years earlier as part of an exchange between publishing houses. The visit turned out to be decisive for the course his fiction would eventually take. Tišma writes that he was struck most of all by

the absence of an element which for me always plays the role of a proxy indicator, of a gauge for the measure of human manifestations. By that element, I mean Jewishness, which in my consciousness is linked indissolubly to Poland through the idea of Galicia, and which no longer exists in Poland. Not in Lublin, which I didn’t succeed in visiting and where once—as I know from literature—everything swarmed with black caftans and hats and curling side-locks and guttural voices and lively gesticulation. Not in Warsaw, where each apartment house in the Ghetto offered shelter to an entire tribe—now in place of the Ghetto there stands an enormous empty field with a stereotyped monument in the middle and new apartment blocks in the background. Not at all, for in Poland, out of every hundred Jews only one survived—40 thousand out of 4 million—and that one doesn’t seek to revive the old community on the basis of those who are left, but flees from it, for it reminds him of the gas chambers.

The conspicuous absence of Jewish communities and the material traces of them that remain in the built environment—as well as the reluctance of Jewish survivors to seek each other out—are subjects Tišma returns to again and again in the Novi Sad novels, often repeating some of the very same language. By following this fixation, we can trace his development as a novelist, from The Book of Blam’s elegiac visions to the acidic bitterness of Kapo.

The Book of Blam is bookended by scenes of its protagonist interacting with sites that were once synonymous with the city’s Jewish population. In an early chapter, Miroslav Blam wanders through the former Jew Street, located just off of Novi Sad’s Main Square. Once a bustling if untidy commercial district, its shops have since been remodeled, and every one of Jew Street’s former inhabitants is now dead. Perversely, Blam claims to find the community’s wholesale erasure “soothing,” as “it relieves him of the conflict he used to feel when confronted with the dark, tense faces, the rolling eyes, the guttural voices fulsomely praising their wares and humiliating him with reminders of his background.” But Tišma’s narration quickly undermines Blam’s attempt at disavowal, revealing that “he could not help missing the more enterprising tribe to which, even if reluctantly, he had belonged.” In the novel’s similarly ambivalent conclusion, Blam attends a performance by the Novi Sad Chamber Orchestra at the city’s former synagogue, which, lacking a congregation, has been converted into a concert venue. At first, he is transported by the playing, feeling “completely at ease, surrendering to the tones that enter and pervade his being like a second bloodstream”—until the intermission, when a chance meeting with the Jewish realtor who sold his father’s house underlines the significance of this space. After Blam returns to his seat, the remodeled building suddenly “looks inane to him, or rather, unreal, ghostlike.” He can no longer lose himself in the music; encountering another Jew has shattered the renovation’s illusion of futurity.

In The Use of Man, this ghostlike feeling is summoned by the sight of an abandoned childhood home. Vera Kroner is the only member of her family to come back to Novi Sad after the war. Her brother, a Partisan, has been executed, as has her father, who refused to join the transport to Auschwitz, and her grandmother, who was ushered to the gas chamber as soon as they arrived. Her mother, who is not Jewish, has emigrated to Germany with a new husband. When, upon her return, Vera approaches the former Kroner house alone, she finds that while it “looked the same as always . . . she had the feeling that she was entering yet another cemetery.” At the same time, she shuns the flesh-and-blood Jews whose presence in the city, however diminished, might help to dispel her morbid feelings, avoiding them even more strenuously than she had before the camps, when she was “afraid of peculiarities of any kind” and “disgusted by the mystical curses that spewed out of the semidarkness of Grandmother Kroner’s room.” To Vera, Judaism is not a religion, a set of rituals, or an orientation toward God; it is reducible to an essential difference that condemns and relentlessly pursues her.

Blam’s vacillation and Vera’s shame curdle into Lamian’s full-fledged contempt; indeed, Kapo’s protagonist is drawn as an archetype of Jewish self-hatred par excellence. It was as a child in Bjelovar, we are told, that Lamian first concluded that Jews were “repugnant” and “offensive” and that “their offensiveness led one to the idea that they should be got rid of.” Like much of Lamian’s raving throughout the novel, this recollection is not entirely trustworthy, since it’s part of an ex post facto attempt to rationalize why he became a kapo, the kind of man who “had broken people’s heads with a club, forced them into the water to drown, and bought the compliance of starving women prisoners for a slice of bread and a swallow of warm milk.” He settles on a soothing narrative of predestination: History merely created the conditions for the evil that was always within him to emerge; “he had been born a Kapo and was therefore free of all responsibility . . . Relieved of the burden of his sins.” This exculpatory conclusion also relieves him of the burden of acknowledging his own trauma, the psychic disfigurement that is not in fact essential to his character but the product of ostracization, violence, deprivation, and hate. Lamian is right that his actions were shaped by history—just not in the way he’d like to think.

Understanding the roots of his pain does not make Lamian’s tortured internal monologue any easier to stomach. Where other characters in the Novi Sad novels focus their shame ever further inward, Lamian sprays his outward in indiscriminate bursts of invective, in thoughts that frequently conform to the commonest tropes of Nazi propaganda. He disdains Jews for their “rootlessness, their lack of allegiance to country or language, or an allegiance they changed according to need, contemptuous of all affiliations and borders”; he dismisses them as “Marxists, Freudians, Esperantists, feminists, nudists, supporters of every revolution, receptive to every novelty,” people who “scampered here and there like mice.”

It isn’t only Nazi rhetoric that Lamian’s language calls to mind: These are accusations that have long been wielded by Jews against each other. In particular, many Zionists have assailed diaspora Jews in precisely these terms since the earliest days of the movement. As the Israeli philosopher Eliezer Schweid has written, “the rejection of Jewish life in the Diaspora . . . is a central assumption in all currents of Zionist ideology,” and a particularly extreme form of this rejection is evident in the thinking of prominent Zionists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. To the Russian Labor Zionist Yosef Haim Brenner, the diaspora Jew was, in Schweid’s paraphrase, “a deformed human being, a tissue of life without honor or beauty, and warped intellectually.” Brenner’s fellow Russian Labor Zionist Aaron David Gordon accused Jews of being “a parasitic people,” writing, “We have no roots in the soil; there is no ground beneath our feet . . . Every alien movement sweeps us along, every wind in the world carries us. We in ourselves are almost nonexistent, so of course we are nothing in the eyes of other peoples either.” In an 1898 speech, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, founder of the right-wing Betar youth movement, announced, “I am a Zionist, without a doubt, since the Jews are a very terrible people, [whose] neighbors justly hate them.”

Despite sharing at least superficially in Zionist beliefs about the brokenness of diaspora Jews, Lamian disapproves of the project of state-building in Israel in no uncertain terms. At one point in Kapo, perusing a newspaper, he reflects:

Jews, his kinsmen, the sons and grandsons of his contemporaries, former inmates of the camps, stood in tank turrets and drove, flags waving, through undefended settlements, through human flesh, ripping it apart with machine-gun bullets, rounding up the survivors in camps fenced off with barbed wire. This revolted him.

Later, Lamian returns to this image of murder and imprisonment. He makes its resemblance to the atrocities of the Holocaust explicit with an apparent reference to the Sabra and Shatila massacre of 1982, in which the Christian Phalange militia—abetted by the Israeli Defense Forces—murdered thousands of Palestinians in two Beirut refugee camps following the Israeli invasion of Lebanon: “The strong ones were all in Israel, with the sons they had fathered there, and those sons now fenced off others with wire, opening the wire only to let in the mercenaries who slaughtered in their stead, just as the Ustaši used the starving Gypsies in Gradina.” Lamian thus reveals his Judeopessimism to be even more profound than the most radical Zionist’s. To him, a militarized ethnostate is not the guarantor of Jewish survival, but only Jewish extermination’s grotesque inverse.

Political developments within Yugoslavia around the time of Kapo’s publication would have made Tišma sensitive to the destructive uses to which the legacy of the Holocaust could be applied, of which Israel’s dispossession of Palestinians is just one example. In the aftermath of World War II, President Josip Broz Tito had downplayed the specificity of Jewish suffering in order to bind together the two dozen ethnic groups comprising the new Yugoslavian state as having an equal stake in the triumph over fascism. But after Tito’s death, as the Republic lurched toward dissolution, the plight of Yugoslav Jews became a useful analogy for nationalist movements looking to assert their own victimhood amid escalating ethnic conflict. The anthropologist Marko Zivkovic has argued that such rhetoric aided the rise of Serbian nationalist Slobodan Milošević as tensions flared between Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo in the mid-1980s. Milošević would eventually face several counts of genocide and crimes against humanity at the Hague for his role in the persecution and extermination of non-Serbs in Bosnia, Croatia, and Kosovo, including the 1995 massacre of 7,000 Bosnian Muslim boys and men in Srebrenica. But he wasn’t alone in riding the wave of this historical appropriation: Jewish suffering, Zivkovic notes, “was misused by Serbs and Slovenes, Albanians and Bosnian Muslims,” both because it connoted moral authority and because “the link that came to be established between the Holocaust and the state of Israel helped promote the perception that to be a victim of a genocide is to be entitled to a state.” Tišma, who in Kapo writes that nations are “directed by dark forces, by the need to dominate, to dominate in order to perpetuate themselves,” wanted no part in the bloody contest that was beginning to erupt around him.

Indeed, just a few years after the release of Kapo, Tišma emigrated to France, where he remained for much of the ensuing Yugoslav Wars. “I had had enough of the nationalist euphoria” is how he sarcastically put it to The New York Times when the paper profiled him in 1997, by which point he had returned to Novi Sad. The piece is revealing of Tišma’s brittleness, the extent to which the anger and despair evident in Kapo had ossified in the intervening decade. He insists at one point that “there are no ordinary people; every man, especially male, is a criminal.” The totalizing nature of this statement may have been new for a writer who once claimed that fighting evil with “black and white declarations” was tantamount to covering it up, but his belief in the male predisposition to violence—especially sexual violence—wasn’t. In the Novi Sad novels, any amount of power, no matter how abject its circumstances, is inevitably accompanied by rape and exploitation.

The Use of Man’s depiction of Auschwitz centers on the camp brothel, where Vera Kroner is trafficked shortly after her arrival. In the novel’s lone first-person chapter, her experience there is rendered in unbearable detail, from her forced sterilization (“I saw a long drill-like needle that ended in a corkscrew, then felt a burning between my legs”) to the psychopathic brutality of the SS sergeant who oversees the “house of pleasure” and regularly beats the women in it to death with a club, replenishing their ranks from the cattle cars that continue to deposit human cargo at the camp. Even liberation does not really end Vera’s ordeal. When she returns to Novi Sad, her body is the object of intense attention at the post office where she finds work: Men’s “roving hungry” eyes “[assault] her,” trying to “slip under her dress, down her breasts, between her thighs.” When the post office’s secretary—a former Partisan officer—comes to her home unannounced in the night, Vera allows him to sleep with her. Soon a whole string of men from the office arrive on her doorstep, offering gifts of wine, rationed materials, or cash in exchange for sex. These encounters fill Vera with “remorse, disgust, but she was accustomed to that, and decided it was an inseparable part of sexual coupling.” In Tišma’s world, it is.

In the Novi Sad novels, any amount of power, no matter how abject its circumstances, is inevitably accompanied by rape and exploitation.

Kapo represents Tišma’s fullest and most distressing exploration of the link between power and sexual violence. If Jewish men like the stranger Lamian glimpses at the café in Zagreb arouse his ire, that’s nothing compared to the resentment he harbors for Jewish women, whose bodies are sites of both fascination and revulsion. The novel continuously emphasizes the suspect abundance of their flesh; to Lamian, they are “grotesque primeval deit[ies], the totem[s] of a tribe to which he had never wanted to belong but which had now subjugated him to its avenging faith.” In other words, he cannot forgive Jewish women for making him a Jew, and so he rejects the attraction he feels for them with the most violent means at his disposal. As a student, he publicly rebuffs the romantic overtures of a Jewish woman named Branka while possessing her body in private; as a kapo, his proclivities find a far more brutal outlet.

Rather than being eliminated by the camp’s “desolation and stink of the dead,” Lamian’s libido continues to defiantly assert itself in captivity. When his Kommandoführer notices him ogling female prisoners, he communicates that Lamian should feel free to act on his urges. His subsequent conversion of a toolshed into his own personal house of pleasure—detailed in two shockingly matter-of-fact paragraphs that unspool over the space of three pages—is stunning in the extent of its premeditation, the bartering, subterfuge, and patience it requires. He soon perfects a routine, raping women who are selected for him by the leader of an adjoining female barrack and offering them a few morsels of food in return. Helena Lifka is not the first nor the last of his victims, but she is the only Jew he lures into his shed, and it is her face that continues to return to him years after he leaves Auschwitz, with its “big lips,” “[b]lue saucer eyes, from which the tears flowed like water from a spring,” and “protruding white teeth that made her resemble a clown.” When, decades later, a chance discovery makes Lamian think that Helena may be alive and well in Yugoslavia, the terror of recognition gives way to something more tantalizing. For too long, he has lived in fear of his kapo past being uncovered even as unabsolved guilt drives him to psychosomatic illness and the brink of suicide. Perhaps there is one last thing he can extract from Helena Lifka: if not forgiveness, then relief from the secrecy that has deformed his life.

As Lamian begins to look for traces of her, he is thrust back into memories of Auschwitz powerful enough to disrupt his present reality, which transform the whole world into “a camp of his own, a camp for him alone.” Only in this final prison does Lamian realize what he believes has been obvious to Helena from the start: that in tormenting her in that toolshed, he was only playacting the degradation to which she—and he—had already been subjected, humiliating himself with compensatory gestures that reproduced the hierarchy of violence without relieving his bottomless terror. “The clown wasn’t she, as it had seemed to him then, but he,” Lamian concludes, raising his wrinkled hands to his face “to rip off that clown’s mask.

Is it any surprise that in the end there is no one to whom Lamian can show his true face? When he goes to the address at which Helena Lifka is registered, he finds only her cousin Julia Milčec, who has heard neither of Lamian’s crimes nor much else about Helena’s experience of Auschwitz, which she was always reluctant to discuss. Helena has recently died of cancer, and Julia has nothing to offer him but this information and some old photographs.

His quest having come to an unsatisfying end, Lamian is nonetheless reluctant to leave the woman’s home, which seems to him “a part of paradise.” It is the mirror image of Vera Kroner’s cemetery-like house in The Use of Man, marked not by extermination but by stubborn life, however circumscribed. “Outside there was horror, desolation, an icy whirlwind that pierced him to the marrow of his bones,” but inside, Lamian is safe—“just as he had been safe in the toolshed at Auschwitz . . . as he listened to the camp’s waterfall babble of death rattles and prayers and danced to frighten a prisoner named Helena Lifka.” While the analogy initially seems horrific, a final insult to Helena as she lies cold in her grave, a closer look reveals something epiphanic in this line. Throughout his life, Lamian has rejected the possibility of Jewish fellowship: with Branka and his parents before the war, with other prisoners in the camps, with a kindly judge and his beautiful sister-in-law after. Now an old, solitary man, there is no time left for him to make another choice. But in this squalid house that smells “of old things and the old bodies that had lived among them, lived with their painful memories of terror and violence,” Lamian can see at last that instead of being destroyed by his Jewishness, he might have made a home in it, among people who quietly understood him.

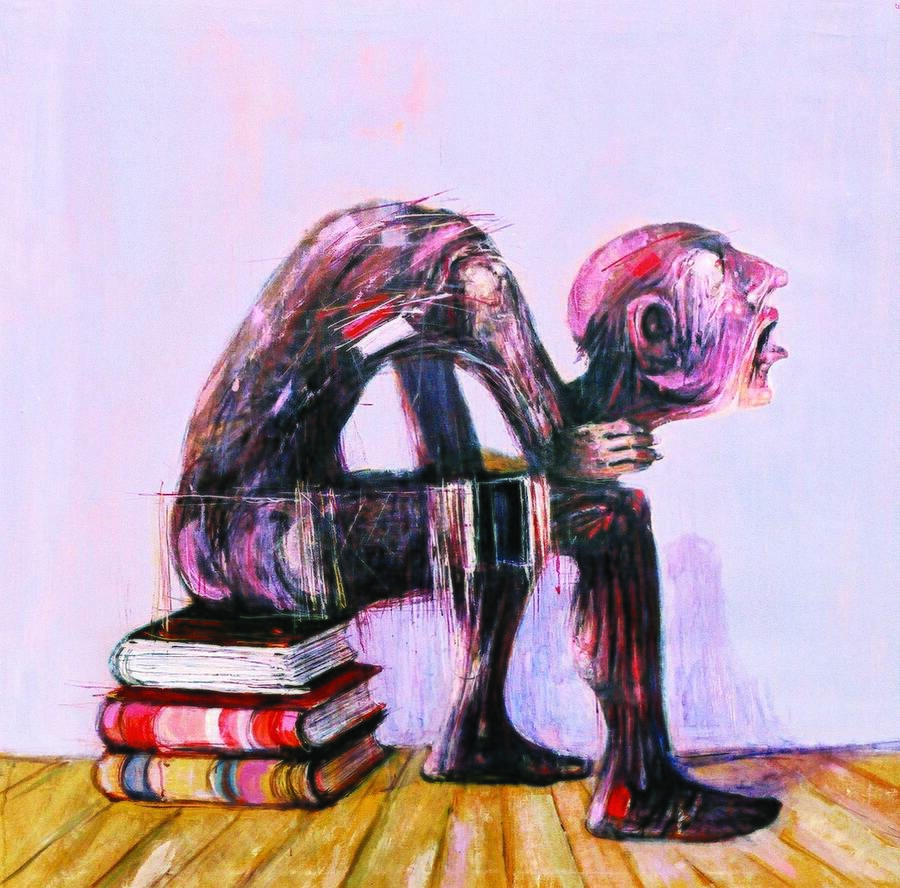

The futility of this belated realization is an appropriate capstone to Tišma’s trilogy. By this point in his career, he was far from sanguine about the ability of the written word to prevent atrocity or even to accurately represent it. In a testament to their essential inadequacy, the Novi Sad novels are full of discarded books, from the ransacked library of Vera Kroner’s erudite father in The Use of Man—a stand-in for the tragic consequences of the liberal faith in reason—to the illustrated volumes of Holocaust history that Lamian can’t tolerate for more than a handful of pages in Kapo, deriding them as “ashes from the ashheap . . . bones from the boneyard. Specimens, exhibits.” Tišma hadn’t always been so skeptical. In 1956, he publicly supported a novelist who’d been attacked by a critic for the crime of writing from the perspective of an Ustaše soldier. Against this condemnation, Tišma offered a political defense of literature, arguing that “the evil which has accumulated in our times can only be cleaned out with long-term catharses, for which art is the appropriate medium and the artist, who brings to life and motivates evil within him, the most appropriate mediator.” As the years wore on, his faith in art’s ability to carry out this cleaning evidently waned. Yet he remained committed to the project of inhabiting human depravity in his own work. A lifetime of proximity to violence may have destroyed his hope, but not his conscience.

Jess Bergman is an editor at The Baffler and a contributing writer for Jewish Currents.