Strange Tales

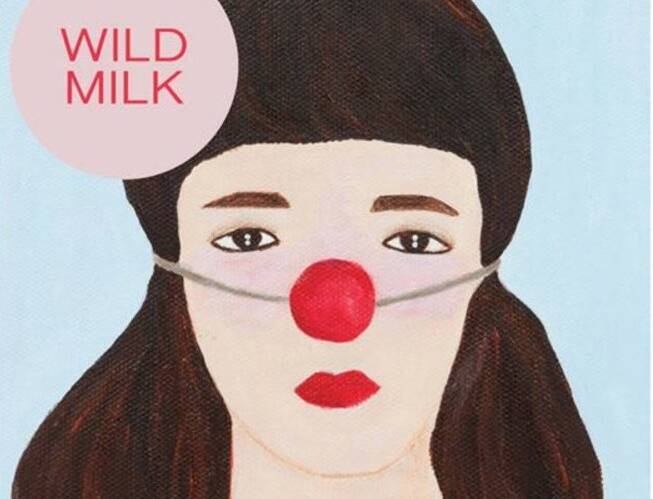

Sabrina Orah Mark’s Wild Milk reconfigures shattered fairy tales into surreal new fables.

Discussed in this essay: Wild Milk, by Sabrina Orah Mark. Dorothy, 2018. 168 pages.

ANY FOLK STORY, when pressed, fractures into a thousand versions, each with its own internal details and strangeness. There are a hundred girls in an enchanted sleep; a hundred boys transformed into animals; a hundred siblings rescuing each other, over and over again, from a false friend, a wicked king, a murderous mother.

In Wild Milk, Sabrina Orah Mark has taken the shattered fragments of fairy tales, nursery rhymes, and characters from the Torah and pieced them back together into two dozen strange mosaics. In these reimagined fairy tales, there are ties of experience that bind closer than blood; there is guilt and anxiety, willful ignorance and absurdity—not to mention cannibalism, parasites, and one extremely dreadful home movie. There is a presentless presence to these stories: a sense that something is haunting them which might be yet living. Can one be haunted by something that is not yet dead?

Chief among the specters that haunt Wild Milk is the subject of motherhood, and it is largely through the stories’ fairy tale elements that the strange permutations of motherhood come into play. This is no surprise; after all, in many fairy tales, a person longs so strongly for a child that a hitherto everyday object—a toy, a vegetable, a bag of gold—turns into flesh and blood. Yet, for Mark’s characters, children are the focus not of longing so much as a kind of befuddled intensity. Children are the source of a spiraling confusion that is at once threatening and absurd. In “Spells,” the narrator’s nine sons transform into daughters; these daughters are enormous, demanding, and infested with lice. The narrator and her husband move through their house slowly, lethargically, though it has become a site of soft torment. “Peace is what pain looks like in public,” the narrator notes after she and her husband play the part of a happy couple for their nine terrible daughters.

Stepmothers abound. One story is, in fact, titled “Stepmother”: here, the eponymous character is told by her children that she is hateful because she smells like Florida. In “I Did Not Eat The Child,” the narrator’s stepdaughter is constantly forgotten by all except the stepmother, who focuses more on her stepdaughter than on any of her other children. The stepdaughter of “I Did Not Eat The Child” is a ghost, although it is not clear whether she is dead or not. What is clear is that she is, like all of the girl children of Mark’s stories, “gigantic.”

It is not all fairy tales in Mark’s stories. Louis C.K. makes an appearance as the narrator’s husband in the dreamlike “Let’s Do This Once More, But This Time With Feeling,” which is more about the claustrophobic relationship between the characters than about the actual person. The story “Tweet” plays on today’s double meaning of “follow,” with the narrator and her friends “following” a rabbi across town and through swimming pools. In the title story, a mother drops her son off at daycare only to be informed by the teacher that he will not drink from the bottle his mother left for him. “The milk you left was wild,” says the teacher. “Please bring better milk.”

Every story in Wild Milk is sharply surreal, yet some cut more deeply than others. For instance, “My Brother Gary Made A Movie & This Is What Happened” is a slightly altered version of a story that first appeared in the anthology of reimagined fairy tales My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me (ed. Kate Bernheimer). True to its fairy tale form, the story is a retelling of Giovanni Batiste Basile’s story “The Young Slave.” Gary, the narrator’s brother, is making a movie (a “moobie”) called “My Family”; fittingly, the actors consist of every member of Gary’s family, with the exception of the narrator. The movie, Gary tells the narrator, is about the Holocaust, though it seems to consist mainly of the entire family—parents, grandparents, some cousins, an aunt, and the narrator’s other 11 brothers—piling in a heap behind the couch. At one point, Gary climbs a ladder and reads aloud the Ten Commandments.

“There are these scrambled eggs in Barcelona,” Gary tells the narrator, a non sequitur that, as is clear from Gary’s habitual deployment of malapropisms, is about neither scrambled eggs nor Barcelona. In the slippage of word and meaning the narrator locates a source of tenderness—for her brother, her family, her displacement from the center of the story. In this slippage we also find a confusion inherent in a particular kind of experimental fiction: when a story tells you what it is about, can you believe it? Gary claims that his film is about the Holocaust; the structure and language of the story dispute this by scribbling an outline of an argument for the impossibility of representing or capturing the Holocaust at all. It is a strange fact of criticism that one might read a story which claims not to be about something and immediately suspect that it is; yet what to do with a story that tells you what it is about with a straight face and no apparent dissembling beyond its own surrealism?

The surrealism of Mark’s stories originates as much in the language as in the strange structures and fantastical, folkloric source material. Throughout Wild Milk, language is flexible, wriggling, and alive. Poetry is a palpable presence; concepts become objects, and those objects grow limbs and begin moving about on their own. Perhaps I am leaning too hard into the body horror of Mark’s stories: they are not, precisely, horrific. One might even call them whimsical, but whimsy implies something one doesn’t need to think too hard about. Whimsy suggests innocence, and these stories are too knowing, too winking for innocence. Mark’s stories want to fool you into thinking they are cute, into feeling that mixture of tenderness and disgust that veers toward condescension—all so they can sweep the rug out from under you at the last second.

Eleanor Gold is a marketer, recovering academic, and reviews editor at Full Stop who still writes about experimental fiction and the Anthropocene.