A one-act play from 1908. Translated from the Yiddish and introduced by Eddy Portnoy.

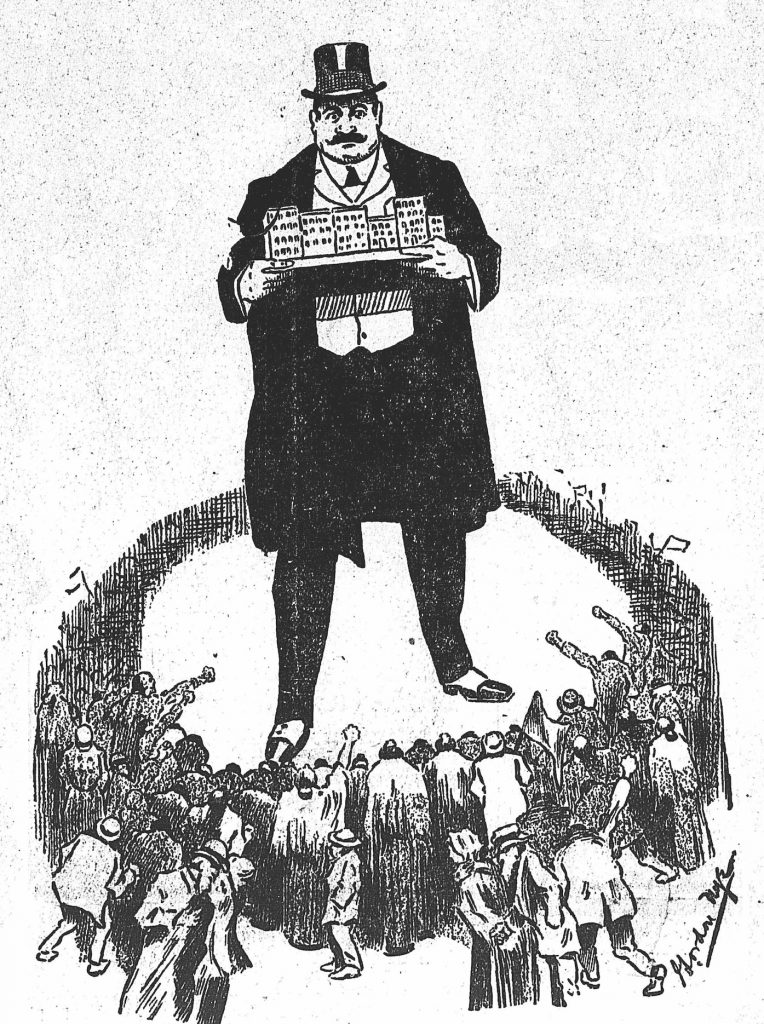

WHEN JEWISH IMMIGRANTS packed the tenement houses of the Lower East Side, Brooklyn, and Harlem during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they faced momentous struggles. In addition to living typically six per family in cramped 300-square-foot apartments, they worked physically exhausting and spiritually demoralizing jobs, from street peddling to 12-hour shifts in stifling factories. The police hassled them mercilessly. Brutally exploited by both their bosses and their landlords—typically also Jews who had arrived in America earlier—immigrant Jewish labor agitators came to understand that their numbers meant power. They organized strikes not only for better wages and shorter hours in the workplace, but also for manageable rents and improved living conditions.

During the years 1907–1909, there were dozens of rent strikes in New York’s immigrant neighborhoods. Picket lines were set up in front of buildings with exploitative rents, many of which led to altercations with landlords, their hired goons, the police, and police marshals. Women were often at the forefront of these protests, as vividly depicted in newspaper accounts from that time. An article in The New York Evening World about a Lower East Side rent strike in January 1908 reported: “There was a riot at No. 113 Monroe Street, where nine families were evicted by Marshal Harris. Mrs. Levinsky, one of the rebellious tenants, living on the top floor, assaulted Mr. Altman, the agent of the property, with a pitcher and drove him into the street. There he was set upon by a band of women and badly beaten.”

These protests were front page news in the Yiddish dailies. The Lower East Side’s best-known poet, Morris Rosenfeld, grasped the importance of the 1907–8 rent strikes, fictionalizing them in a short one-act play called Rent Strike, appearing below in a new translation. The play was published on January 12th, 1908 in the Forverts, the largest socialist newspaper in New York and one of the many Yiddish outlets committed to covering the strikes. In the span of the short play, Rosenfeld maneuvers from melodrama to comedy to pathos, all within a dramatic framework of intracommunal and intrafamilial strife. The reveal—that Yankel Schwartz, the odious landlord, is the brother of Mrs. Lempel, a leader of the rent strike against him—underlines the wrenching intimacy of these disputes.

Rosenfeld was better known as a poet who wrote about labor issues; Rent Strike may not be his best literary work. But it does reveal how rent strikes animated immigrant Jewish communities in early 20th-century New York City. Such strikes were often successful. Although Rent Strike likely had nothing to do with it, the day after it appeared in print, dozens of Lower East Side landlords whose tenants were on strike relented, and lowered rent for nearly 500 families.

—Eddy Portnoy

CAST OF CHARACTERS:

Yankel Schwartz: A rich landlord, about 50 years old with a rotund body and a common face

Mrs. Lempel: His sister, a poor widow

Bobe Gitele: Their mother; an old, sick, and poor woman

Leybe Gaytz: A tall, thin Jew; a real estate agent

Mrs. Tchotchke[1]: A wealthy landlady

Mrs. Knup: Mrs. Tchotchke’s housekeeper

Boodle[2]: A judge

Others: Landlords, strikers, people, police, etc.

The play takes place in a Jewish neighborhood during our time.

SCENE ONE

A meeting in an office over a saloon in which landlords and landladies in big hats with long feathers, wearing diamonds and pearls, have gathered. Waiters are running about with glasses of beer and cigars on trays for the men, and with seltzer water, herring sandwiches, and sour pickles for the ladies. Yankel Schwartz enters with a cigar in his mouth and wearing a silk top hat. He rolls in and takes his place as the chairman of the meeting.

Schwartz: (Bangs the marble table with a hammer) Ladies and gentlementshn, I hereby open thisth busin-esth meeting. We mutht now get down to businesth[3].

Gaytz: Seconded! I’d like the floor.

Schwartz: (Angrily banging the hammer on the table) Sit down! Leybe Gaytz always has to be first. You’re just a real estate agent. Let the landlords speak first.

All: Mr. Schwartz is right. Sit down!

Gaytz: (Sitting down) Seconded!

Schwartz: Sisters and brothers, you know how much anger the goddamned sensationalist papers have cooked up with our tenants, and that they’re all on strike for cheaper rents. There are already thousands of them, and more are expected to strike. What should we do?

First Landlord: Brother Chairman, ladies and gentlemen, my brothers, my advice is to make a deal with them. We should promise them a month’s free rent if they will sign two-year leases.

Gaytz: Seconded!

Schwartz: (Hitting the table with the hammer) Sit down! (Gaytz sits as if it wasn’t him being talked about)

Second Landlord: Brother Chairman, ladies and gentlemen, and my brothers. I say we give ‘em nuttin’ an’ t’row ‘em out inna street.[4]

Third Landlord: Brother Chairman, ladies and gentlemen, and my brothers. The man who refuses to give them anything probably has empty apartments. He wants us to throw out our tenants so he can scoop them up. I protest!

Gaytz: Seconded! The agents agree.

Schwartz: The agents again. Sit down! (Gaytz sits) I also say we shouldn’t give in so easily. And almost all of you already know that I don’t have any empty apartments in the Bronx. Fine— no one will have to move.

Gaytz: Seconded!

The sound of an orchestra is heard playing “The Marseillaise.”[5]; soon thereafter, shouts are heard: “Down with the bloodsuckers.” Those in the meeting look around, confused.

Third Landlord: Brother Chairman, ladies and gentlemen, and my brothers. Do you hear what’s going on outside? They won’t give up.

Mrs. Tchotchke: Brother Chairman, ladies and gentlemen, and my brothers and sisters. I’m alright. Let my housekeeper tell you . . .

Mrs. Knup: Make it so I shouldn’t hear or remember to help.[6]

Gaytz: Seconded!

Schwartz: Sit down!

Mrs. Tchotchke: My husband, may he rest in peace, left me with a whole block of tenements. I got rooms front and back and always have neighbors. By me, thank God, it’s always full up. They’re protesting? Let them protest! I won’t lower my prices, not one cent. My apartments are beautiful—ask my housekeeper.

Mrs. Knup: We should all have such beautiful apartments like my Missus has. Oy, such apartments!

Schwartz: My advice is to go see Judges Poodle and Boodle. They’ll fix everything. They’re ours, they are! The police have clubs and New York has prisons. In my buildings the main leader is a woman. She instigated the whole thing and got everyone involved—that’s what my building manager tells me. I can’t get involved with my tenants. I don’t even know their names. But tomorrow morning I have to be in court to deal with them. I’ll have to grease the judge’s palm, but good . . .

Gaytz: Seconded! The agents will contribute.

Schwartz: Sit down! Again with the agents! Let the landlords talk.

First Landlord: I’ve got trouble with my second mortgage.

Second Landlord: And I’ve got trouble with my third.

Third Landlord: I’ve got trouble with my fourth.

Fourth Landlord: And me with my fifth.

A Landlord: Brother Chairman, ladies and gentle-men, and my brothers. In the meantime, let’s make a deal with these losers, these radicals. Later on, when the market gets busy, we can make them pay through the nose.

Gaytz: Seconded! The agents like that.

Schwartz: Alright—let’s vote on it.

Third Landlord: I gotta suggestion: those who have empty buildings in the Bronx shouldn’t get to vote.

Loud protests break out. Beer glasses and sandwiches go flying through the air, one of which knocks off Mrs. Tchotchke’s hat. “The Marseillaise” is heard from outside.

Gaytz: Seconded!

The curtain goes down. It briefly goes dark and after a while, it becomes light.

SCENE TWO

A courtroom on the Lower East Side. Milling about are cheap-suited lawyers, politicians, lobbyists, detectives, thieves, pimps, prostitutes, swindlers, paid-off witnesses, toughs, robbers, burglars, landlords, real estate agents, building superintendents, beaten and bloodied rent strikers, rent collectors, police officers, and the just plain curious. Judge Boodle holds court.

Boodle: (To a beaten-up striker, bloody from head to toe, barely able to stand up. A policeman is holding him.) So, you’re a rent striker, eh? An insurgent trying to violently overthrow the government. You’re looking for sympathy, revolutionary?

Striker: (Pointing to the policeman holding him) This policeman almost killed me—and for nothing. I committed no crime.

Boodle: What do you mean? You won’t admit it, rioter? You want to turn America socialist. Free rent for everyone, fly the red flag. You attacked the police.

Policeman: Your Honor, he tore a button off my uniform.

Striker: He beat me bloody with his club.

Boodle: What are you on strike for? If the rent is too high, just move out!

Striker: Sure, when food is expensive, we should fast. If gas is too expensive, we should sit in the dark. If coal costs too much, we should freeze. If the work loans are cheap, we shouldn’t work. If the rent is too high, we should sleep in the street. Where are the laws of justice that should protect the citizens who live in this country? Why did America declare independence from England?

Boodle: You’re an anarchist. Take him away! Forty-eight hours in prison. (He is removed.)

Boodle: Schwartz versus Lempel.

Mrs. Lempel and Bobe Gitele enter. The old woman is raggedly dressed, weak and sick, barely able to stand. Schwartz enters and stands opposite. When he sees his poor sister and old, abandoned mother, he goes pale and begins to shake, but acts as though he doesn’t see them.

Schwartz: Your . . . Honor . . .

Bobe Gitele: (Seeing her son) Murderer! (She faints but is revived. Opening her eyes, she wants to run to him, but instead shakes from age, anger, and sadness.) Yankel, my child . . . let me go to him . . .

Boodle: (to Schwartz) Who is this old woman?

Schwartz: She . . . she . . . is . . . I don’t . . . know . . .

Mrs. Lempel: A lie, Your Honor. This old woman, sick and abandoned, is his mother. Our mother, who he left on the verge of death and who he refuses to support—not even one cent. She’s with me, a poor, weak widow—his dear sister. I have to go to work to support my children and my mother.

Boodle: (To Schwartz) Is this true?

Schwartz: She . . . says so . . .

Boodle: And you?

Schwartz: I . . . I don’t . . .

Boodle: (To Schwartz) What’s your complaint?

Schwartz: This woman, Your Honor, (he points to his sister) is my tenant. She instigated all of my tenants to participate in a strike and engage in violence and was caught beating up the building housekeeper.

Bobe Gitele: Vey iz mir. What’s she saying?

Mrs. Lempel: It’s a lie, Mama. He’s exaggerating.

Bobe Gitele: Vey iz mir . . .

Boodle: So, violent threats and attempted murder . . .

Schwartz: I thank you . . . but . . . she is a poor woman . . . I’ll lower her rent a dollar a month, but the other strikers will have to move.

Mrs. Lempel: (Furious) He should throw me out as well, Your Honor, me with our old sick mother, this murderer. He’s already thrown me out a few times when I asked for help for our sick mother. This former tin peddler, who now pals around with millionaires, abandoned his own mother. Damn him and his friends, with their rotten prisons they call apartments. Plague-ridden traps that spread death and disease among the poor. Damn him and his buildings. I didn’t know who my landlord was, but now that I do, he shouldn’t make any more money off my pathetic toil, this scumbag. Arrest me, Judge, if you want. Arrest me and my mother, because she depends on me for everything. Arrest us!

There is great disquiet in the courtroom: Women are crying, even policemen and murderers are moved. The judge sits deep in thought.

Curtain falls.

“Tchotchke” is Yiddish slang for a woman, and also means “trinket.” It is used here derogatorily.

“Boodle” was Yiddish slang for “corrupt” or “counterfeit.” It is a borrowing from English slang, in which the meaning is the same.

Rosenfeld rendered all of Schwartz’s speech with a lisp. For the sake of readability, only Schwartz’s first line of dialogue has been translated this way.

The syntax and accent of this landlord’s speech reveals his working class origins.

The French National Anthem and a popular anthem of international radical protest.

This is likely intended as nervous babble, an indication that she doesn’t want to get involved.

Morris Rosenfeld (1862–1923) was a Yiddish poet, dramatist, editor, and publisher. He was born in Poland and immigrated to New York in 1886. His collected poems were published under the title Gezamelte Lieder in 1904.

Eddy Portnoy is the academic advisor and exhibitions curator at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. He is the author of Bad Rabbi and Other Strange but True Stories from the Yiddish Press (Stanford University Press, 2017).