Malak Mattar began painting during the 2014 assault on Gaza, when she was just 14 years old. Encouraged by her friends and family, she quickly gained the recognition of activists and artists both in Palestine and abroad. At only 18 years of age, her work has been exhibited worldwide, including in England, France, India, Spain and the US.

In socially conservative Gaza, it is rare for a woman to travel alone. But as an exceptional young artist and student, Mattar had an opportunity to study abroad, one not afforded to the vast majority of those in the Gaza Strip. So she made a pact with her father: if she got the highest score on the Tawjihi, an examination akin to the SAT, he would allow her to attend university abroad. She succeeded, scoring first in the Gaza Strip and second in all of Palestine. She has earned a full scholarship to Istanbul Aydin University, where she will begin her studies in Political Science and International Relations in September of this year.

In partnership with the podcast Unsettled, we present the following interview with Malak Mattar by Unsettled producer Emily C. Bell. This interview has been edited for style and clarity. You can subscribe to Unsettled wherever you get your podcasts, and stay tuned for their episode with Malak, which will be released as part of their upcoming series on Gaza.

Unsettled Podcast: Could you speak a little bit about your experience during Operation Cast Lead in 2014 and the discovery of your artistic practice during this time?

Malak Mattar: In 2014 it wasn’t the first time I witnessed war, it was actually the third time so I felt like, numbed, like I’m just losing my feelings, like I’m no longer . . . I just felt that I could no longer hold this inside me and that I need to discharge this negative energy. I was just laying down in my bed and I said, I can do something, so I fetched my watercolors. It was really bad quality, my first drawing, it was a woman with an embroidered dress and outstretched arms and under those arms destructing [sic] buildings because of what the occupation did to the Gaza Strip. But this painting was really cheerful because the sky was blue and the girl was smiling and so it was a really optimistic thing, it didn’t really show that I’m living under this pressure and stress, that I might lose my life within a second like many civilians in Gaza that had nothing to do with resistance or Israel.

The first time I did my sketches was the first time that I felt what I’m born to do. I still get this feeling every time I start a painting. Now I’m 18 years old, as I grow I feel that I have more responsibility, that I need to be an ambassador. I need to capture the sadness and the depression of the Gazan people in my paintings. This is the thing I could do with what is happening now, people killed in peaceful demonstrations. You know that Razan al- Najjar was a medic, 21 years old, and also Yasser Murtaja, he was a journalist. They were on duty and they also had their uniforms on, the white coat and the press vest [when they were killed]. And every time I call my family and my friends, everyone is in deep depression because of what is going on. It’s really terrible what Gazans are witnessing.

UP: Do you see art as playing a role in the movement for Palestinian freedom?

MM: I think that art is playing an enormous role in the Palestinian issue. I believe that art is an honest and direct way to address people outside Palestine. When I look at people’s messages and comments, they feel that, you just made us aware of Gaza and aware of Palestine. I feel that sometimes a piece of art can be more honest than any piece of writing because any artwork is just a story of Palestinian people.

UP: So do you consider yourself an activist?

MM: Wow, that’s a very . . . well, I don’t . . . this is actually not my goal, I’m not striving to be an activist, I just prefer to be a peaceful representative. I don’t like to be in a position where I’m fighting, where I’m in conflict. I just prefer to be an artist, myself. But also a voice, I need to be a voice.

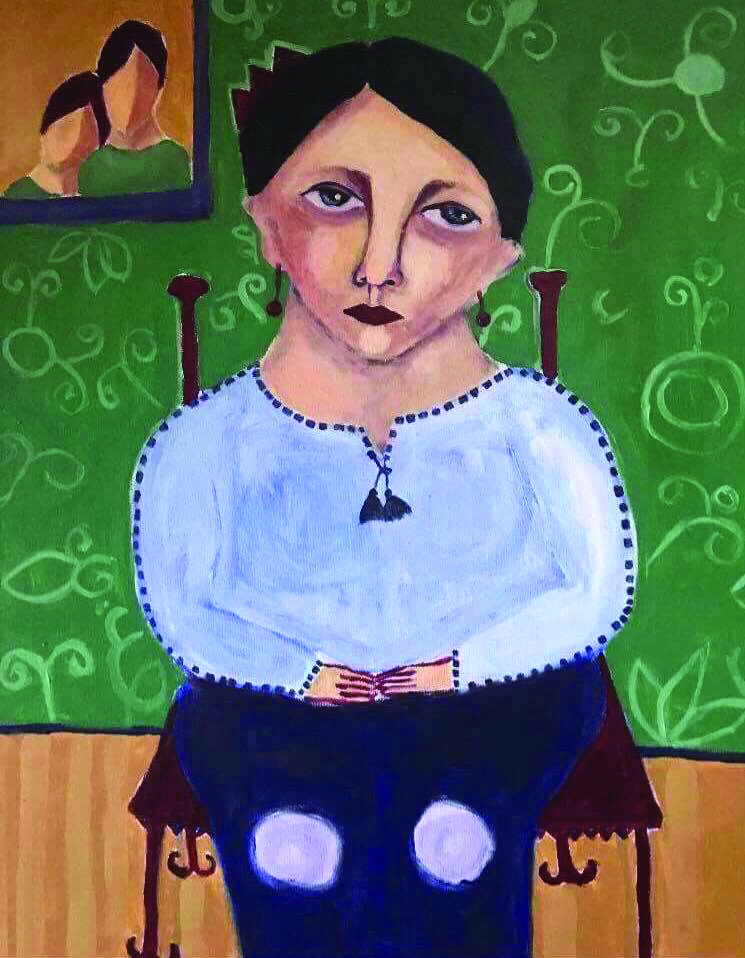

UP: There’s a painting of a woman holding a white bird [Ed. note: The Dove, pictured above]. I was wondering if you could tell me about that one.

MM: I actually painted this in my first months in Istanbul. It was really difficult for me as I had to move and I just felt really homesick, with every meaning of homesick. I was actually inspired by a song in Arabic. It says, “for a bird who’s traveling, please go to my country and say salaam.” It turned me really emotional, so I decided that I needed to draw something about it. It’s mainly a self-portrait. Many people think that if I travel from Palestine I will just forget about it, I will just get busy, but it turned out that I have my country inside me whenever I go. In Gaza, like, architecture and the streets, is really simple compared to Istanbul, and still I really feel honored that I’m from there because it played a great role in how I am now.

UP: Why do you focus on women and specifically portraits?

MM: I feel strongly compelled to defend the rights of women. Women play a huge role in society, taking care of the children, and children are everything in [Gazan] society. Palestinian women are really special women, really strong. In many paintings, I’m inspired by my mom and my grandmom, by the way they think, the way they feel, the way they cope with the situation.

My mom is an English teacher and played a great role in me becoming an artist because she really believed in me, letting me travel, while no one could easily in Gaza. It also isn’t easy for any girl to travel on her own without a man with her. It’s from religious and social perspectives, so although she got many criticisms from relatives, from her colleagues, she believes that I will be something great. The first person that I’m keen to hear her opinion is my mom. Her comments are always honest. Also my grandmom. Actually we used to live in one building, so she took a great interest in my life . . . um, sorry . . . (crying). She passed away six months ago.

UP: I’m so sorry for your loss.

MM: It’s okay . . .

UP: Your art has traveled around the world and has been displayed in many different locations but it was also displayed much closer to Gaza, in Jerusalem. Can you speak a little bit about the experience of having your art displayed there?

MM: Yeah, I actually had two group exhibitions in Jerusalem, supported by the American consulate. For any Gazan, going to Jerusalem is like a dream, and praying at Al-Aqsa Mosque, it’s not something easily done. So I went and for the first time, I saw Jerusalem. I felt that the air is kind of different from the air in Gaza, you know. It was heart-wrenching to see Al-Aqsa Mosque, and how holy it felt to pray there, and even walking in the narrow streets . . . it’s really something. It took quite a while for me to understand that Jerusalem is also my country; being trapped in a specific place makes it difficult to accept.