A Nation Like All Others: Gershom Scholem and the Paradox of Zionism

How one people’s “independence” became another’s catastrophe.

Discussed in this essay: Stranger in a Strange Land: Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem, by George Prochnik. Other Press, 2017. 522 pages.

ALONGSIDE THE 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, the 70th anniversary of the UN partition plan and the 50th anniversary of the Six-Day War, 2017 marked another important anniversary for Israel: “120 years of Zionism,” according to the World Zionist Organisation. Although the Zionist movement is actually far older, dating back centuries, what was really being celebrated last August was the 120th anniversary of the First World Zionist Congress in Basel, in August of 1897.

Theodor Herzl was the convenor: a serious, big-bearded man now recognized as not only the founder of modern Zionism, but also, in the eyes of many, Israel itself. “Were I to sum up the Basel Congress in a word,” Herzl wrote in his diary a few days after the event, “. . . it would be this: At Basel I founded the Jewish State. If I said this out loud today I would be greeted by universal laughter. In five years perhaps, and certainly in 50 years, everyone will perceive it.” And 51 years later, in 1948, the state of Israel was declared.

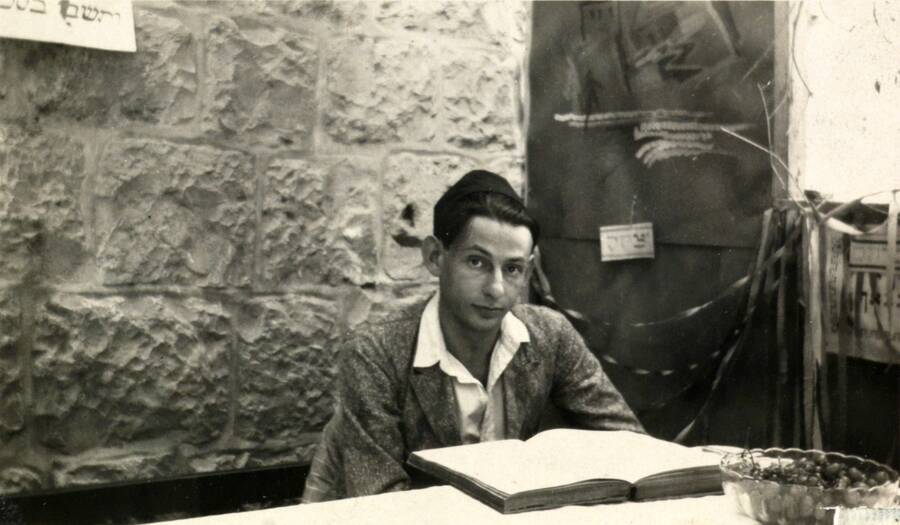

Gerhard Scholem was born in Germany the same year as Herzl’s diary declaration. While he would go on to become one of Israel’s most celebrated scholars and cultural exports, admired by figures as diverse as Hannah Arendt, Allen Ginsberg, and Harold Bloom, his life began as a young Jewish boy in Berlin, with a bourgeois father ready to trade in the family’s Jewish ties for European assimilation. Young Gerhard had other ideas. “Papa,” he announced one day, “I think I want to be a Jew.” “Jews are only good for going to synagogue with,” his father snapped back. And so Gerhard’s childhood became an inverted cliché: a rebellious attempt to enter, rather than escape, his family history, heritage, and tradition.

By the time he was a teenager, a portrait of Herzl hung on his bedroom wall (albeit as a Christmas present from his mother). He learned Hebrew and immersed himself in Jewish and Zionist literature, growing increasingly disdainful of Western consumerism. He began an intense and lasting friendship with Walter Benjamin, debating and disagreeing on the liberating potential of Zionism versus Socialism. But despite Benjamin’s ambivalence towards Zionism and Scholem’s usual deference to his older friend, on this matter, Scholem would not be swayed. He continued his studies in Judaism in Germany, bided his time and then finally, after a two-week, eighteen-hundred-mile trip, Scholem arrived in Palestine: aged 25, alone and at home, in a place he had never been before.

George Prochnik’s book on Scholem, Stranger in a Strange Land: Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem, is a remarkable retelling of a remarkable life. The book is plural: intimate and sweeping; biography and autobiography; an account of a friendship and the author’s failed relationship; a story of a nation and the Zionist movement itself—a dream made material with devastating effect. “Arriving in Palestine in 1923 in the early years of rising Jewish immigration, continuing to write, teach and lecture through all the subsequent riots and wars almost to the day of his death in 1982,” Prochnik writes, “Scholem’s life unfolded in tandem with the creation and ideological evolution of the State of Israel.” What’s more, through his family and friends who resisted Palestine’s pull, Benjamin among them, Scholem’s story also hints at the fate of some of those who stayed behind.

It’s as if, from the mythical moment of their shared beginning, the year of Herzl’s prophetic diary declaration in 1897, Scholem somehow encapsulated his nascent new homeland’s complexity: the determination and confused direction, the contradictions and desires—like two mazes twinned by hidden tunnels, always connected but never quite the same. Scholem arrived in Palestine in 1923 as an “idealistic, if idiosyncratic Zionist,” Prochnik writes, who “exhibited unrepentant multiplicity.” He was a self-described “religious anarchist,” more interested in the mystical ambiguities of the Kabbalah—Judaism’s obscure spiritual strand—and the nihilism of Nietzsche than any biblical declaration in the Torah.

Although Scholem desired, like all Zionists, the “destruction of the reality of exile” for Jews, he could never partake in their nationalist obsessions. Indeed, long before he landed in Palestine, Scholem had strayed from the man whose portrait once hung from his bedroom wall. Herzl’s dreams of “a Jewish state,” he decided, tackled “the Jewish problem [of exile] merely as a form instead of in its inner essence.” What if the Jews’ exile was more than just a geographical condition, he wondered. What if, after so many centuries, it was an exile that could no longer be cured by aliyah, Zionism’s prescribed “return” to Eretz Yisrael? Whatever the answers to these questions, Scholem was convinced that establishing a Jewish state in Palestine would simply mean “forging new chains out of the old.”

Nevertheless, in September 1923, there he was, in Palestine, a colonized country under British control since 1920. And for all his doubts and idiosyncrasies, Scholem adjusted to his new life swiftly and smoothly. He dropped his German name: Gerhard became Gershom, the Hebrew name Moses gave to his son after escaping from Egypt. “For I have been a ger [stranger] in a strange land,” Moses declared. Scholem felt no compunction drawing such links between Jewish mythology and himself.

His professional career in Palestine took off with the founding of the Hebrew University on Mount Scopus in 1925. Scholem was promptly appointed as a scholar specializing in Kabbalah, one of the first posts of its kind. During his studies in Germany, he had already established himself as an expert in this niche, bewildering field, and he was now determined to make it more mainstream. By the beginning of the 21st century, decades after his death, his mission was either complete or corrupted: the Kabbalah became an unlikely Hollywood trend, an object of the Western consumerism he loathed but more popular than he ever could have envisaged. Scholem had been more hopeful that the Kabbalah’s poetic engagement with exile might encourage a gentler, more humanist politics in Palestine.

He was a committed advocate of binationalism in the region—granting equal rights to Jews and Arabs in a unified democratic system—and a leading member of Brit Shalom, a small pacifist group dedicated to this cause that also included his friend, the first chancellor of Hebrew University, Judah Magnes. But if the notion of binationalism irked many Zionists, who focused their attentions instead on establishing first a Jewish majority and then a separate Jewish state, it irked Arab Palestinians as well. Binationalism may have been a benign idea, even progressive in its context (not to mention now), but it still struck many Palestinians as offensively presumptuous. It also did nothing to stem the flow of arrivals: between 1922 and 1927, Jewish immigration from Europe to Palestine almost doubled, from 83,000 to 150,000.

Meanwhile, the World Zionist Organization was purchasing more and more land from Arab Palestinians “whose miserable economic plight,” Prochnik writes, “–partly caused by [British] Mandate taxes–gave them no choice but to accept the best price offered.” In August 1929, the unaddressed anxieties of Palestinians escalated into widespread violence. Riots swept across the country: 13 Jewish communities had to be evacuated and 133 Jews were killed, while 110 Palestinians died at the hands of British police.

Britain’s subsequent efforts to ease Arab concerns floundered with their failure to acknowledge Arab nationalist aspirations. Arab solidarity increased, but so too did the determination of Zionists. David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s future first prime minister, penned a memorandum titled “Fortification.” It called for “expanded migration, particularly of young people, increased mobilization of financial resources, land settlement, . . . and upgrading the settlements’ defensive capability.”

Under these darkening skies, Scholem was genuinely pained. His journey from Berlin was part of the problem, he realized, that pushed Palestinians out of their own land. But it was a problem to which he saw was no easy answer. His Zionist dream twisted into violence, but as is the way with dreams, he felt powerless to control its course. “After all,” he wrote to his friend Martin Buber in 1930, “we have to realize that our interpretation of Zionism does no good if someday (and there is no mistaking the fact that the decisive hour has come) the face of Zionism, even that which is only turned inward, should prove to be that of Medusa.” He completed a poem soon after, bleak and broken, titled “Encounter with Zion and the World.” It ends with the lines:

What was within is now without,

The dream twists into violence,

And once again we stand outside

And Zion is without form or sense.

And yet, as Prochnik notes, “one aspect of the decision to be in Palestine appeared more enlightened with time: the decision not to be in Germany.” By 1933, 10 years after Scholem left, Hitler was in power and Mein Kampf had sold over a million copies. These developments not only reinforced the Zionist case for a Jewish state, they also inadvertently strengthened the means to achieve it.

As European Jews fled their own darkening skies, arrivals in Palestine soared. By 1935, reports estimated that 5,000 refugees were arriving every month, among them highly qualified scholars and professionals who would likely never have come otherwise. Imports and exports both grew by approximately 300% between 1931 and 1935, and the price of land went up even higher, further alienating poorer Palestinians.

One person who didn’t arrive, despite Scholem’s best efforts, was Walter Benjamin. Scholem repeatedly pressed his friend to make the journey, partly because of the situation in Europe and partly because Judaism was, in Scholem’s view, “the crucial literary experience of which [Benjamin] stood in need to come really into his own.” Yet Benjamin dodged and diverted, delayed and delayed. “Wait for me with your heart,” he urged Scholem, but Scholem saw how “at all times other projects prevented him from entering the world of Judaism.” In 1933, Benjamin came close to killing himself, going so far as to write farewell letters to friends and draw up a will leaving Scholem all his manuscripts. He persevered, but the event was only postponed. In 1940, Benjamin took his own life in Catalonia, after fleeing from Nazi Germany. “I’ll never recover from this terrible blow,” Scholem told a friend.

In some ways, nothing embodies the contradictions of the Zionist movement more than these few years. In an attempt to escape a history of sub-citizen status, racist stereotyping, persecution, and extermination, Jewish emigrants sought to secure for themselves all the protections of a Jewish nation-state, meanwhile expelling Arab Palestinians from the same land and dispossessing them of the the very protections Jews sought. One people’s “independence” became another’s catastrophe. Perhaps this is what Scholem meant when he spoke of the “gaping paradox in the life of a committed Zionist.”

IF IT IS OFTEN said that every biography is a disguised autobiography, Prochnik’s account does not pretend otherwise. His book on Scholem is unashamedly about himself as well, interweaving both the personal significance he finds in Scholem and his own turbulent decade living in Israel with his then-wife Anne. Prochnik is a skilled storyteller, and here he adeptly draws the two disparate narratives into one affecting tale. After a while, the links between the two stories go mostly unmentioned or teased out; they are felt but never forced. And in their coming together, as Georges Perec wrote in his own fictionalized memoir of the Second World War, W (double-vé), they “make apparent what is never quite said in one, never quite said in the other, but said only in their fragile overlapping.”

Prochnik is a Jewish convert whose move to Israel in the 1980s from New York—soon after Scholem’s death—is motivated by Scholem-esque impulses: an assimilating Jewish father, a loathing for the West’s world-conquering market individualism, and a desire to escape into its alleged antithesis: Judaic history and community, threatened and empowering. But for all Prochnik’s enthusiastic expectations, as time passes and events swirl and he and his wife struggle to find fulfilling employment, far from feeling more settled in this new and ancient homeland, Prochnik is left feeling only “more and more estranged.”

The situation in Palestine is one reason, but he feels many more immediate ones besides. With every passing week, his neighborhood in Jerusalem grows more religious and conservative as Israeli society as a whole becomes more capitalist and consumerist—two contradictory forces that appear to alienate him equally.

Meanwhile any rare moment of political hope feels destined to be followed by deepened despair. So when, for example, Prochnik cheers as the historic Oslo accords are signed in September 1993, signaling a possible end to 26 years of Israeli occupation of Palestine, the new height is only a set up for a new low. A few months later, during Ramadan in early 1994, a Brooklyn-born Orthodox Jew steps into Hebron’s Ibrahimi Mosque and opens fire, killing 29 Muslim worshippers and injuring 125, before being beaten to death by some of the survivors. The Hebron Massacre sparks the first string of Palestinian suicide attacks.

A year later, as Prochnik and his wife celebrate again when parliament votes to approve the second phase of the Oslo Accords despite rising hostility, a young Orthodox Jew shoots and kills Rabin. A snap election is called to elect a new leader and Benjamin Netanyahu defies the odds to become Israel’s youngest prime minister. He was the populist strongman Zionists like Jabotinsky had always wanted, and that Zionists like Scholem had always opposed. “A man should not give up his country and his home with that kind of ease and joy,” Netanyahu had thundered weeks before the assassination, as crowds at his rallies chanted for Rabin’s death. “Only one who feels like an invader and a thief behaves in such a fashion.” After Netanyahu’s electoral victory, many proclaimed that Rabin had been assassinated twice.

By this point, Prochnik is alienated on all sides—by the free-marketeers and the religious orthodox, the right-wing violence, the political situation in general, and his own personal troubles with work. While studying at the Hebrew University, he sees his attempts to set up a new course on Jewish thinkers in Europe thwarted by conservative-minded superiors. Even his relationship to Anne is unraveling and his academic thesis on Poe, once a refuge, starts to feel cold and distant; it leaves him feeling, he says, “increasingly exiled from myself.” Exile, in other words, is everywhere. A move made to cure the condition only served to exacerbate it.

And so the couple undertake yerida, a reverse aliyah, a heretical departure from the Promised Land to the diaspora. Out of one history, into another—a diasporic history thousands of years old, which Herzl’s Zionism so readily dismissed—and leaving all of Israel’s contradictions in place. Scholem always wondered whether Jewish history “would be able to endure this entry into the concrete realm,” because, in a sense, the resurrection of the Jewish people onto the international stage—and the concomitant negation of their history of exile—was the most assimilatory act of all: joining the world of powerful nation-states, with all its dark demands. One wonders whether, to this end, Zionism exiles Jews anew by exiling them from their history of exile. Perhaps this is what Scholem meant when he warned, with his dim hyperbole, that “even if we wish to be a nation like all the nations, we will not succeed. And if we succeed–that will be the end of us.”

Samuel Earle is a freelance writer who lives in London.