Photography by Olivia Walsh

Looking for a Lineage in the Lusk Archive

The records of a New York surveillance committee from the time of the First Red Scare document a radical world—and its demise.

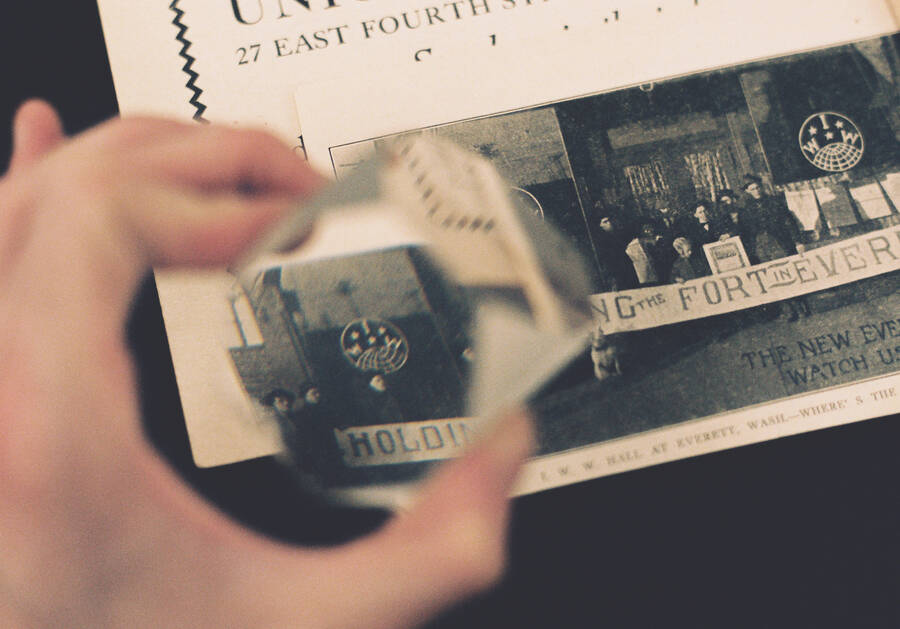

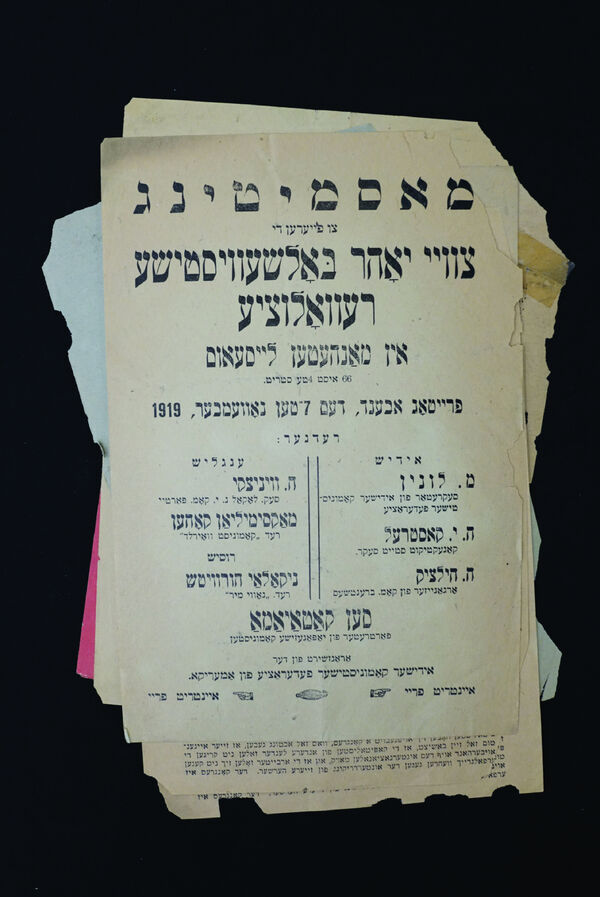

The tan cardstock handbill announces an upcoming event, to be held on November 2nd, 1919: Appearing in Brooklyn for the first time, the Ukrainian Workers Theater will perform a night of drama and music. The event description is printed in Ukrainian, but the vocabulary is simple enough to be deciphered 100 years later by O., a native Russian speaker who grew up with the Odessa-influenced vernacular of southern Brooklyn. The directions—a mix of Ukrainian and English, swinging between the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets—lead to McCaddin Hall in Williamsburg. The building, now a Catholic church and performance space, still stands today, its name written in stone.

A handbill announcing a performance at the Ukrainian Worker’s Theater at McCaddin Hall in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, on November 2nd, 1919.

As teenagers in the early 2000s, we each went to punk shows in the surrounding neighborhoods. We punched our fists in the air and shouted until there was no breath in our lungs. We hurled our bodies into the pit, trusting that the punks would pick us up each time we fell. “United,” B. shouted along with the band Against Me!, “we’ll make them remember our history!” It’s easy to imagine young people filling McCaddin Hall in 1919, feeling their pulses race as they sang along to revolutionary songs.

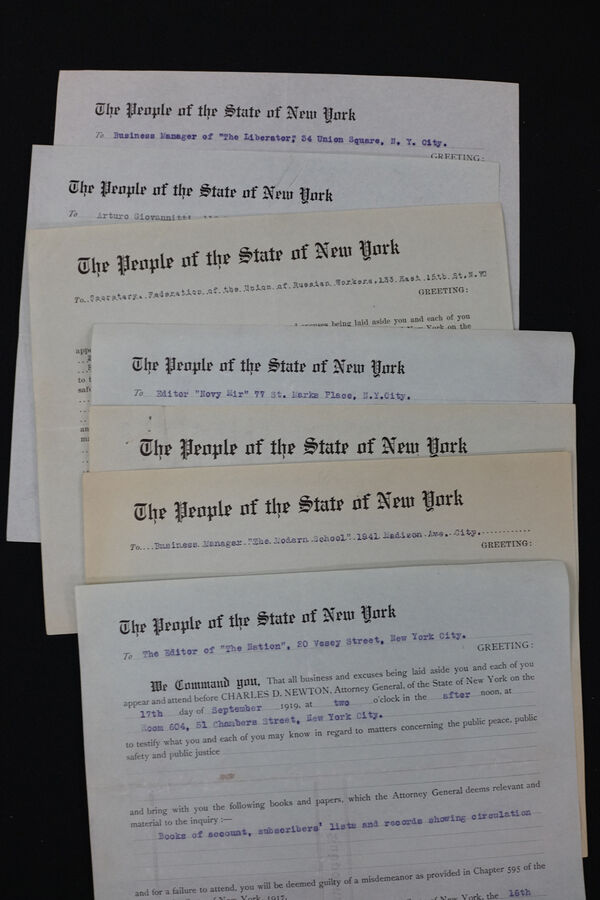

The two of us find the Ukrainian Workers Theater handbill filed away in the New York State Archives in Albany. It is one of tens of thousands of pieces of evidence gathered in an archive called “Records of the Joint Legislative Committee to Investigate Seditious Activities.” It documents the activities of what was commonly known as the Lusk Committee, named for its chairman, State Senator Clayton R. Lusk, which formed in 1919 at the peak of the First Red Scare. The committee, working closely with both local law enforcement departments and federal agencies, was given extraordinary powers to surveil and subpoena people and organizations defined as suspicious under New York State’s criminal anarchy code. A Socialist Party flyer, itself seized and archived by the Lusk Committee, describes the committee as having “an army of troopers, spies, provocators [sic], pettifogging lawyers and press agents, reinforced by a ‘hand picked’ Grand Jury.” It was one node of a nationwide effort to destroy the anarchist, socialist, and radical labor movements of the preceding decades, setting a nativist agenda for years to come. Reacting to organizing by groups like the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in the United States and revolutions in Russia and Germany, state and federal governments unleashed violent suppression campaigns, providing an early blueprint for today’s policing practices, including media monitoring and the use of informants.

In New York State, Lusk’s “army” infiltrated thousands of radical meetings, spying on casual attendees, rank-and-file activists, and high-profile organizers like Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph, feminist union organizer Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, communist journalist John Reed, and pacifist and radical economist Scott Nearing. Their raids led to the criminal convictions of individual activists, the shuttering of entire organizations, and the expulsion of the five members of the Socialist Party in the New York State Legislature. The committee’s work culminated in new state laws used to persecute any suspected radical educator in the New York City public school system and to deport suspected anarchists and communists.

In New York State, Lusk’s “army” infiltrated thousands of radical meetings, spying on casual attendees, rank-and-file activists, and high-profile organizers.

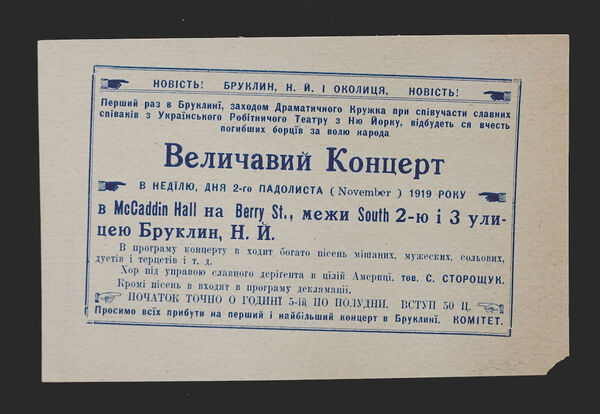

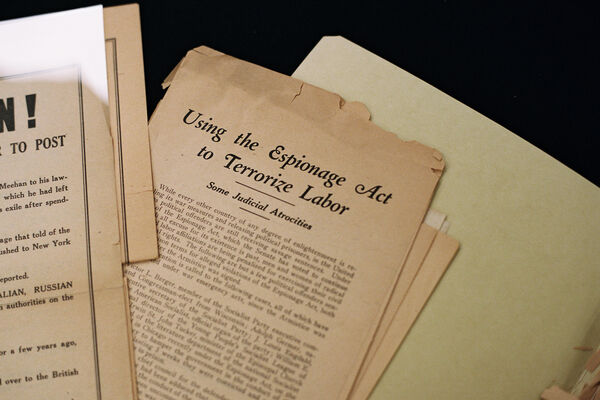

A flyer railing against the persecution of socialists under the federal Espionage Act.

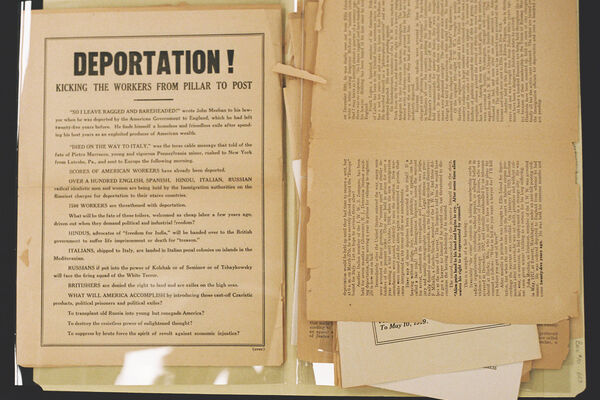

A flyer condemning the US government’s deportations of suspected radicals during the First Red Scare.

What interests us, though, is not just what the Lusk Committee damaged and destroyed, but what it saved: Over the course of its investigations, the committee collected tens of thousands of documents on a critical period in American radical history, preserved by the State of New York in both originals and microfilm to this day. Within the archive, we find polemics by various leftist factions, practical organizing plans, and utopian materials promoting visions of a new world that never came to be. We find flyers for rallies, concerts, and dance parties. We find handwritten personal messages. We find firsthand agent and informer accounts capturing the way people moved, spoke, and lived in communal spaces.

Whether or not these agents and informants fully understood the world they cataloged, their job was to document the dissident culture—understood to be foreign, Jewish, Black, or some combination of the three—threatening the nation. “Not being familiar with the Yiddish tongue,” writes one agent who attended a May Day meeting at the building on East Broadway that housed the Yiddish-language socialist newspaper Forverts (which later became The Forward), “it was not possible to interpret the speeches, but it was not difficult to understand the speakers engaged in a bitter arraignment of the present form of government in America and advocacy of Bolshevism was plainly uppermost in the minds of a majority of the audience.” Eerily, the contents of the archive, collected by nativist politicians, law enforcement agents, informers, and infiltrators, allows the two of us—O., a USSR-born Jewish immigrant, and B., a fifth-generation New York Jew born three miles from the State Library—a chance to access the lives of our spiritual and political ancestors. We are here in search of radical life, which is both suppressed and revealed through state surveillance. By conducting our own survey of the Lusk Committee Archive, we hope to meet our ancestors.

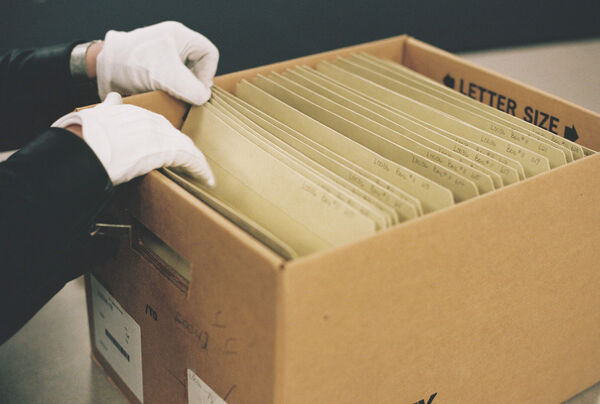

The Lusk Committee’s records are held in the New York State Archives, part of the New York State Library, located on the 11th floor of a Brutalist white marble building called the Cultural Education Center. The center, in turn, is part of Empire State Plaza, a sprawling complex of interconnected government buildings housing New York’s administrative state. We enter the complex through one of the state office buildings and wander the tunnels beneath the plaza until we find our way into the lower level of the Cultural Education Center, which houses the New York State Museum.

About 50 cubic feet of this complex are devoted to housing the Lusk Committee records. Entering the state archives requires an appointment, a signature, and a government-issued ID; leaving requires a search. The process reminds B. of his job teaching at a New York state prison. The difference is that one part of the state wants to keep subversive literature locked in, and the other wants to keep it locked out. Everything in its place.

Inside the New York State Archives, which house the Lusk records.

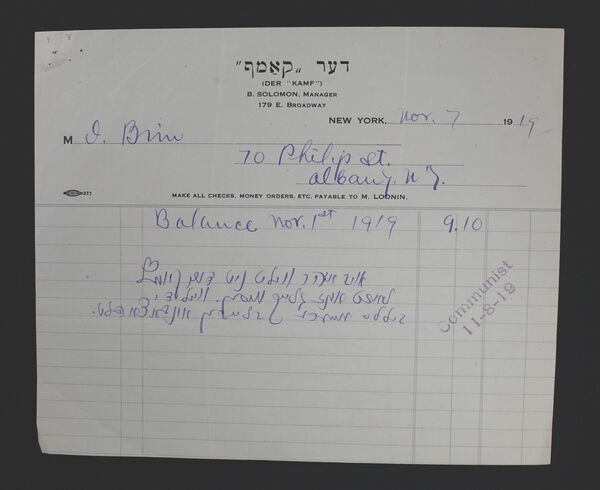

Empire State Plaza was constructed as part of a 1960s urban renewal project that paved over 98 acres of Albany’s old South End, home to some of the same working-class Black, Jewish, and Italian communities the Lusk Committee surveilled a generation or two earlier. A Yiddish-language newspaper overdue payment notice in a seized file lists a Philip Street address about a quarter mile from the State Library. We can each make out a little of the Yiddish—O.’s is a kludge of Berlin German and southern Brooklyn Russian; B.’s, a mix of childhood visits with his grandparents and sporadic academic interest. We both read the language very slowly, sounding out each word.

An overdue subscription payment notice for the IWW Yiddish newspaper Der Kamf addressed to a reader on Philip Street in Albany, New York.

It is harder for us to reckon with the publications translated from Russian and Yiddish, likely by an in-community informant. We wish we could interrogate the informants: Were they threatened with deportation or imprisonment if they didn’t collaborate? Were they offered money or employment? Did they still see themselves as revolutionaries, despite the choices they made? Or did they see themselves as patriots, and this work an attempt to prove their loyalty to their new country? These questions are important: Although we prefer to situate ourselves as heirs to the leftists, the collaborators are our ancestors, too. The communal artifacts of the archive represent a collection of individual lives. We wonder about the people we encounter. What happened, for instance, to the Jewish radical who lived on Philip Street? Did her grandkids flee the neighborhood as Empire State Plaza was being built? Did the community informant who reported on the Union of Russian Workers (URW) meetings feel proud or ashamed after the mass deportation of its members in 1919?

We are both versed in systematic research methods—O. is a policy analyst and B. is a literary scholar—but none of these methods are of particular use as we drift through the Lusk Committee archive. Our time in this space feels like sorting through the apartment of a dead relative, trying to discern heirloom from refuse. Mostly, we sift aimlessly, the grief of failed potential mounting as we pore over flyers about mass meetings, accounts of fiery speeches, and membership rolls of long-forgotten affinity groups.

If there is a manual for the type of research we are attempting, it might be Investigative Poetry by the poet Ed Sanders, who is a link in the chain of radical New York history falling somewhere between us and the generation of 1919. Sanders edited Fuck You, a mimeographed literary magazine that published Beat-era writers like Allen Ginsberg and Diane di Prima, and co-founded the band the Fugs, an important presence in the ’60s anti-war counterculture and an early influence on the punk movement. In his manifesto, he calls on poet-researchers to “surround an item of time / with thick vector-clusters of Gnosis,” using an ancient Greek term for spiritual knowledge to make it clear that he is not simply referring to a mechanical process of data retrieval, but to an almost mystical process of attaining insight into hidden truths. With this goal in mind, we circle and surround this “item of time,” the yearlong campaign of 1919–20.

In a letter written in October 1919, the Bronx-based Marxian Club asked if the Corona Typewriter Company would sell them two of their “good Corona typewriters” on a monthly installment plan. The letter is written on flimsy paper, yellowed and tattered, that shows signs of having been folded into sixths. The type is barely visible. The club, made up of high school and university students, needed the machines so they could start publishing their magazine, The Marxian Journal. We found no further records to attest to whether or not the students got their hands on the typewriters.

The Lusk Committee archive contains many such internal documents—membership rolls, memos, letters—showing the day-to-day work of organizing. Then there are pieces of widely distributed ephemera like newspapers and pamphlets, or flyers for general strikes and “monster protests” held at places like the Harlem Casino and even Madison Square Garden. There is a baffling mix of early Soviet documents that somehow made their way to New York, including not only volumes of Marx and Lenin but also artifacts like an accounting of agricultural yields in central Russia and Soviet interpretations of peasant folk songs. And of course, there are the secret documents, the agent and informant reports.

The Lusk Committee’s primary objective was the suppression of anarchist groups like the Union of Russian Workers, a group of anarcho-syndicalists—that is, revolutionary industrial unionists—formed by refugees from the Russian empire who opposed the Tsarist regime in Russia and capitalism in America. In 1919, the URW had dozens of chapters nationwide devoted to organizing immigrant industrial workers around labor issues that continue to resonate today: long hours, bad working conditions, abusive managers. The pages of the URW’s newspaper Hleb y Volya (Bread and Freedom) transport us to New York City’s Russian People’s House, located around the corner from Union Square, on 15th Street. The house acted as a print shop, a social service agency, and an anarchist infoshop where recent immigrants learned English, listened to political lectures, formed relationships, and talked about building a new world in the shell of the old. On November 7th, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, a young J. Edgar Hoover, who would go on to lead the FBI for nearly 50 years, launched raids targeting the URW in 18 cities, arresting about 1,200 people. A flyer titled “Russian Pogroms in America” wryly notes that, during a different raid, the NYPD Bomb Squad seized books once cleared by the Tsar’s censors. The Justice Department worked quickly to convict, denaturalize, and deport many of the raid’s victims, over 200 of whom were placed on a ship alongside well-known anarchists like Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. (Lusk agents dutifully documented the well-attended monster rallies across New York protesting the deportations, like the one organized by the Federated Body for the Defense of Russian Prisoners in America at the Labor Lyceum in Brooklyn on December 16th, 1919.) The deportees’ final destination was the newly formed USSR. While many on board were skeptical of the Bolsheviks’ centralization of power, some carried hope for the new Russian workers’ state. Arriving in a country in the midst of a civil war, many of the URW deportees were ultimately imprisoned or murdered—not by the Tsarists but by the Bolsheviks.

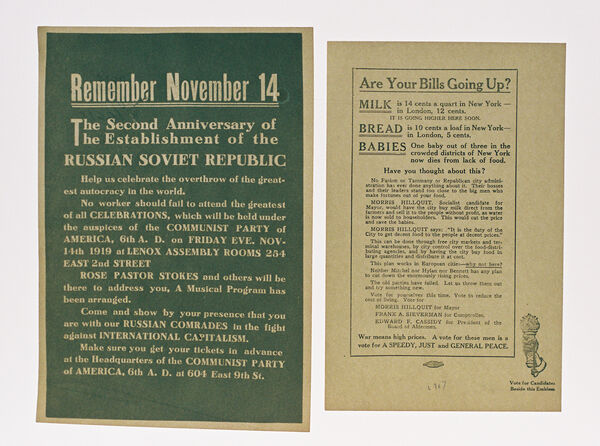

A Communist Party flyer (left) advertising a celebration on East 9th Street in New York City in honor of the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, alongside a flyer outlining the Socialist Party’s platform in the 1917 New York City municipal election.

In addition to immigrant-identified unionist groups, the Lusk Committee actively suppressed homegrown radical labor organizations, including the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Established in 1905 in Chicago, the IWW was an anti-capitalist alternative to the American Federation of Labor (AFL). It was popular across industries, drawing in both American-born and immigrant workers (the archive contains translations of IWW materials into multiple languages, including Ukrainian and Finnish). As part of a wave of repression, many states passed criminal syndicalism laws explicitly designed to outlaw IWW membership. By 1919, the organization was on the defensive. In a text-heavy, four-page pamphlet titled Raids! Raids!! Raids!!! stored in the archive, IWW leader Bill Haywood documents incidents of state violence against IWW chapters in Centralia, Washington; Pueblo, Colorado; Seattle; and Omaha. At least one episode he describes involved the Lusk Committee: A November 1919 NYPD Bomb Squad raid, supported by information collected by committee informants and infiltrators, destroyed the local’s office and left many badly beaten. The second page of the pamphlet includes a heavily underexposed photograph of a trashed office, with papers strewn across the floor, captioned “NEW YORK HALL AFTER RAID.”

The Lusk Archive is filled with lists of names. Many of them were seized wholesale from radical labor and activist groups. One representative document enumerates the dues-paying members of the Jewish Communist Federation, the names—most in English, some in Yiddish—proceeding down the page in two neat columns that gradually veer off course. For government agents—and historians—such lists are useful, because they provide clear evidence of association; for radicals, they can be terrifying. Our identification with the people who signed their names to those lists makes us nervous, but we also share some of the historians’ excitement: We, too, are greedy for evidence that a specific time and place really existed, to picture the sheet of paper passed around the room at a lively meeting and feel the excitement about an upcoming action. Based on our own organizing experiences, we can only imagine that a volunteer was responsible for collecting federation dues and making sure that members signed in. Every such document is the product of unseen labor. In his memoir Left of the Left, Anatole Dolgoff writes of the labor his father, the influential anarchist Sam Dolgoff, performed as a teenage member of the Socialist Party’s youth branch: “He came early, before the audience: swept the floors; swabbed the toilet; arranged the chairs; cranked the mimeograph; distributed the leaflets; hung the signs; set the table, water pitcher, and lectern up on the small stage for the speakers and chairmen; circulated the cigar box to take up collections.” The work of the rank and file is implicit in every organizational document and leaflet captured by the archive.

The Lusk Archive is filled with lists of names.

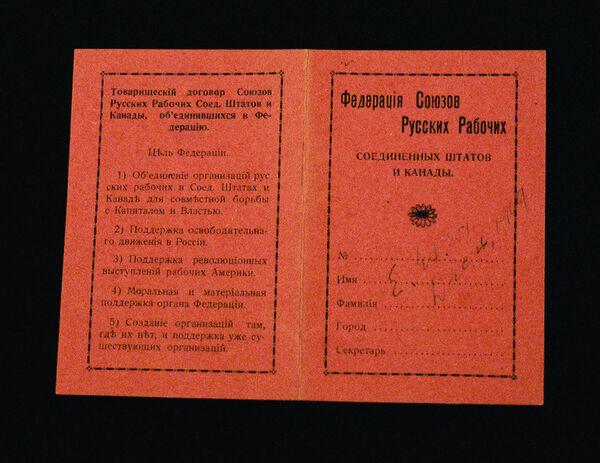

A membership card for the US and Canadian Union of Russian Workers.

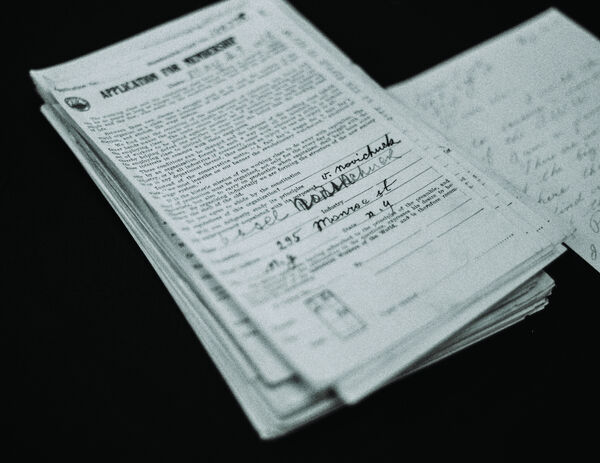

Applications for membership to the IWW, 1919.

In addition to seizing self-generated lists in raids, Lusk agents zeroed in on prominent individuals in their event reports; they are listed by name, while unknown attendees are cataloged through description. (Although photography was an increasingly accessible medium at the time, it was not yet a central part of popular print culture—or, apparently, surveillance practices.) Although the informant’s vignettes are not meant to be literary, their first-person perspective on events reminds us of the stream of consciousness “camera eye” sections of John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy, a project that sought to capture this same period of American history. Rather than snapping pictures, the Lusk agents swing their gaze around like a lens, taking in the faces. One infiltrator describes a speaker at a “Ukrainian Socialist Meeting” attended by 1,000 people, as “James Larkin . . . the only one to speak in English, a big surly looking, aggressive agitator of the roughneck type, who preaches radicalism to the extreme degree.”

The Lusk Committee’s focus on a foreign, destabilizing threat to the United States often fixed the informants’ gaze on Jewish bodies. A report on a Socialist Party meeting at the Brownsville Labor Lyceum in Brooklyn begins: “The assemblage was composed principally of the lower type of Russian Jew to the number of about 500.” Elsewhere, Jews appear through sensory details, as in a report on the May Day meeting at the Forverts building, which describes the space as having a “distinctly foreign atmosphere, to say nothing of the odor which suggested a close proximity to a garlic garden and a gafilter fish [sic].” Jews even appear in their absence: “There were about six hundred people here, mostly Hungarians and Checko-Slovaks,” an informant writes of a May Day festival held by the Hungarian Workmen’s Council in the uptown Manhattan neighborhood of Yorkville. “I saw very few Jews.” If we had any pretenses of being “objective researchers,” these passages destroy them. We are made keenly aware of our countable, objectionable Jewish bodies. The phrase “she was a Russian Jewess, spoke very poor English” feels uncomfortably close for O.

The Lusk Committee’s racial anxieties were also focused on the potential radicalization of New York’s growing Black population, which included internal migrants from the South and immigrants from the Caribbean, through labor organizing. The Lusk Committee was particularly threatened by figures like A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen, editors of the socialist political and literary magazine The Messenger; copies of the publication appear in the archive as surveillance material, even as they are also displayed downstairs in the New York State Museum’s “Black Capital: Harlem in the 1920s” exhibition. Randolph and Owen founded the National Association for the Promotion of Labor Unionism Among Negroes, which worked to integrate Black industrial workers into the labor movement from which they were often excluded. The organization was supported by the United Hebrew Trades (Fareynikte Yidishe Geverkshaftn), an association of Jewish labor unions, as well as the Socialist Party—the kind of evidence of interconnection between Black and Jewish labor groups that the Lusk Committee was on guard for. In his 1975 article “The Search for Black Radicals,” published in the journal Labor History, J. M. Pawa quotes a Lusk informant’s report suggesting that “if the Office of the [socialist daily newspaper] New York Call were raided, evidence would be found to establish a connection between the radical Socialists and the present unrest among the colored populations in various large cities.” As Black activists built institutions and theorized about the nature of the US economy, Lusk agents—unwilling to assign Black people agency—searched for a hidden cabal destabilizing the accepted white supremacist social order.

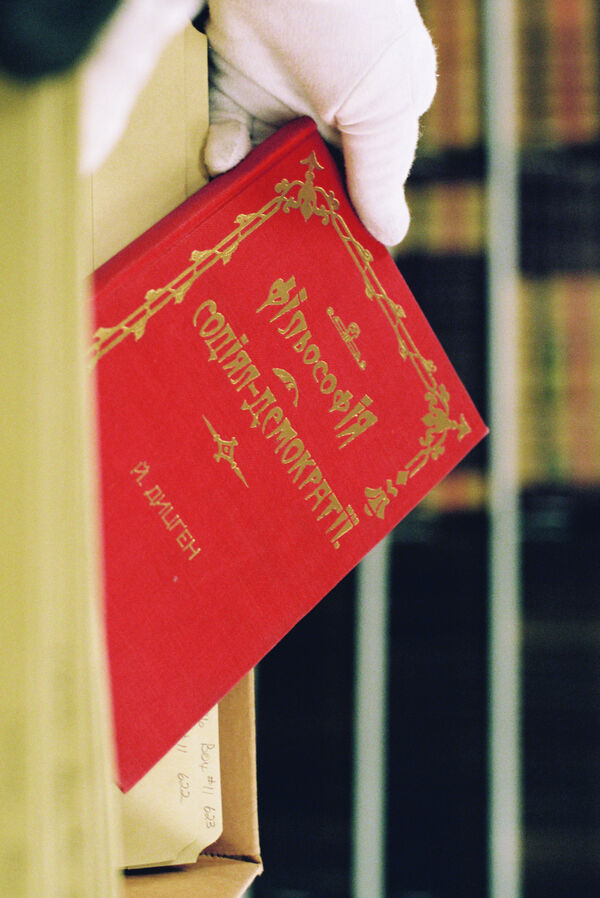

An archived copy of a Ukrainian translation of German philosopher Joseph Dietzgen’s Social-Democratic Philosophy.

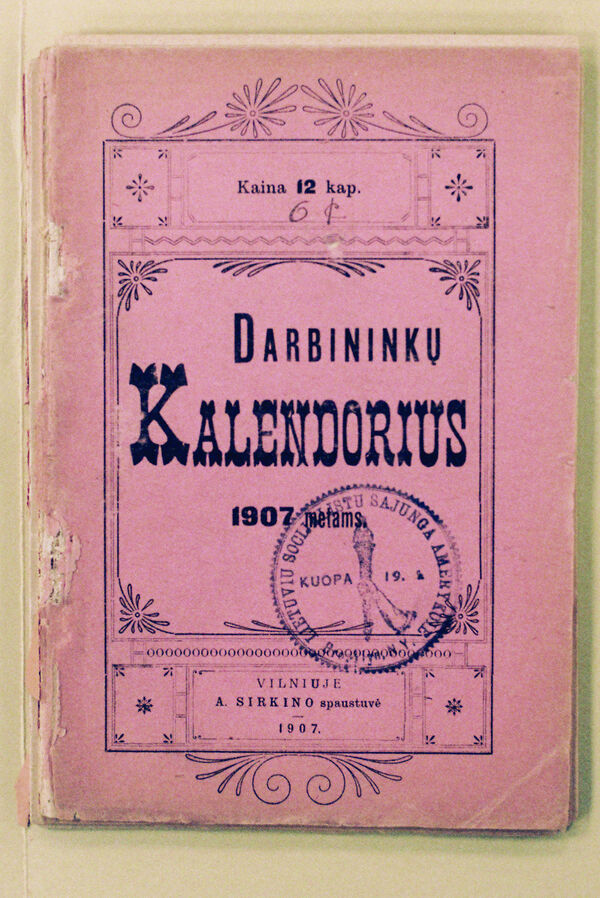

An archived worker calendar published in Vilnius, Lithuania in 1907.

A flyer for a November 1919 mass meeting of the Jewish Communist Federation of America at the Manhattan Lyceum.

The majority of people involved with the organizations surveilled and raided by the Lusk Committee did not languish in prisons or get deported, but they did internalize the persecution. Public associations with radicalism and foreignness were not tolerated during the jingoist period following the US’s entry into World War I in 1917, and large-scale leftist organizing did not fully reemerge until nearly a generation later, during the Great Depression. By that time, the Communist Party had centralized its role in American radical organizing, filling the vacuum of the decimated anarchist and socialist movements. A culture of self-policing emerged among many victims of the First Red Scare and their descendants, who redacted rent strikes and industrial sabotage on the Lower East Side from their family histories. Others pursued a closed-off, paranoid approach to organizing, always keenly aware of the eye of the state.

For the most part, American-born children and grandchildren of these revolutionaries were assimilated into mainstream American culture. Allen Ginsberg’s 1956 poem “America” captures the painful process of losing connection to radical community. In an enjambed memory, Ginsberg turns his gaze back to his childhood in the early ’30s: “when I was seven momma took me to Communist Cell meetings they sold us garbanzos a handful per ticket a ticket costs a nickel and the speeches were free everybody was angelic and sentimental about the workers . . . Scott Nearing was a grand old man a real mensch.” He concludes: “Everybody must have been a spy.” (As a child, B.’s mother took him to hear Ginsberg read in Albany. Such oral transmissions live in us alongside the written ones.)

New York State Attorney General subpoenas summoning the editors of radical publications and members of leftist groups.

In Investigative Poetry, Sanders writes of the Tsarist persecution of poet and novelist Alexander Pushkin for his affiliation with the radicals who would ultimately mount the failed Decembrist uprising in 1825. “During these years of police surveillance,” Sanders writes, “Pushkin gradually began to soften under the pressure, becoming ‘more objective’—that is, secreting his revolutionary politics in narrative.” State policing leads to self-policing. This occurred again during the Second Red Scare, the witch hunt for communists in public service, education, and the media that followed World War II and culminated in the McCarthy hearings. During this period, B.’s grandfather hid a secret row of books behind his public facing books on the shelf, for fear of losing his government job if a colleague visited his home and reported what he was reading. Looking through the documents boxed away in the Lusk Archive feels like rediscovering that row of hidden books.

The Lusk Committee has its own spiritual descendants. The “Demographics Unit” of the New York City Police Department spent more than a decade following the 9/11 attacks surveilling Muslim groups. They targeted immigrant communities with “ancestries of interest,” nearly all of which came from Muslim-majority countries, as well as Black Muslim communities formed in the US. The tactics employed by the Demographics Unit, developed with the aid of the CIA, were remarkably similar to those of the Lusk Committee: Undercover police officers called “rakers” infiltrated communities, targeting mosques, bookstores, and cafés. As with the Lusk Committee, the NYPD has also employed internal informants, known as “mosque crawlers,” to monitor conversations at public gatherings.

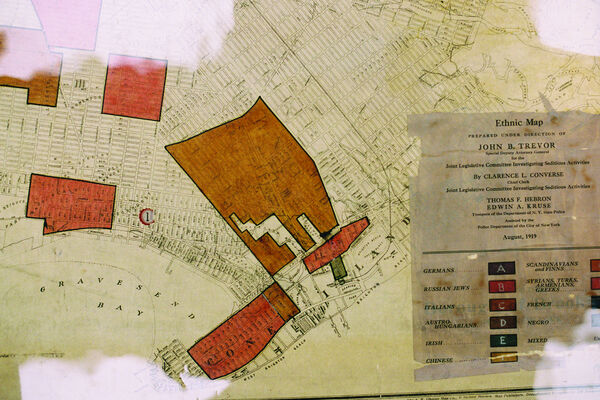

The Demographics Unit’s collection and mapping of data mirrors the Lusk Committee’s preoccupation with spatially locating the state’s radical threat; the Lusk Archive includes hundreds of entries documenting the precise addresses of radical activity. In 1919, the NYPD, along with the New York State Police, used Lusk’s findings to create “ethnic maps” of four New York City boroughs for the committee, forging a spatial link between race, ethnicity, and radicalism. The maps have the feel of an ambitious high school social studies project. The Manhattan/Bronx map, for instance, identifies dozens of ethnic enclaves, colored in on the map by hand: The South Bronx neighborhoods of Mott Haven and Longwood are mostly colored red, for Russian Jews, with pockets of green, for Irish. A portion of Central Harlem, from 125th to 145th Streets, is colored in black and labeled “Negroes.” Radical publishers are marked on the map with blue star stickers, while meeting spaces are indicated with white circles with scalloped red edges. (McCaddin Hall in Williamsburg, where the Ukrainian Workers Theater performed, is number 14 on the Brooklyn/Queens map, mislabeled as Malden Hall.)

In 1919, the NYPD, along with the New York State Police, used Lusk’s findings to create “ethnic maps” of four New York City boroughs, forging a spatial link between race, ethnicity, and radicalism.

“Ethnic maps” of New York City created by the NYPD used Lusk Committee data to identify ethnic enclaves and addresses affiliated with radical activity.

The Lusk Committee’s short-lived investigation and the provincial archive it created are almost quaint compared to modern surveillance apparatuses. There is something haphazard about the materials collected by the Lusk Committee, and about the amateur nature of the reports. Agents frequently write of going home because they couldn’t locate a political meeting. The Lusk Archive also shortly predates the widespread use of “disinformation”—like the attribution of falsified images and documents to targeted groups—which was formalized as a tactic in the Stalin-era Soviet Union, and became a feature of Cold War propaganda. We treat the archive’s contents earnestly, accepting that it is an album of “true” artifacts; in that one sense, we find the Lusk Committee trustworthy. And, of course, it precedes the contemporary security state’s reliance on information technology including social media networks, facial recognition, and other biometric tools.

A century after the height of their exclusions from the United States, most Jews, Slavs, and Italians in this country have assimilated into white America and shed their subversive communal associations. However, Black, Muslim, and Latino communities continue to be identified as racialized security threats to the American “homeland” subject to surveillance and detention. Infiltration and surveillance of racialized communities are now part of the continuous functioning of the state. Federal immigration agencies, with the help of local police departments, target and deport undocumented people, while intelligence agencies work with local police to harass and intimidate Black activists. Across town from the New York State Library, at SUNY Albany, students pursue undergraduate and graduate degrees at the college of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security, and Cybersecurity, preparing for careers in the permanent, professionalized state surveillance apparatus. As a graduate student teaching composition classes at SUNY Albany, B. helps undergraduate emergency preparedness majors develop their writing skills—skills they may use someday to write reports like the ones in the Lusk Archives. Where does the security apparatus start and end? How deeply are we implicated in it?

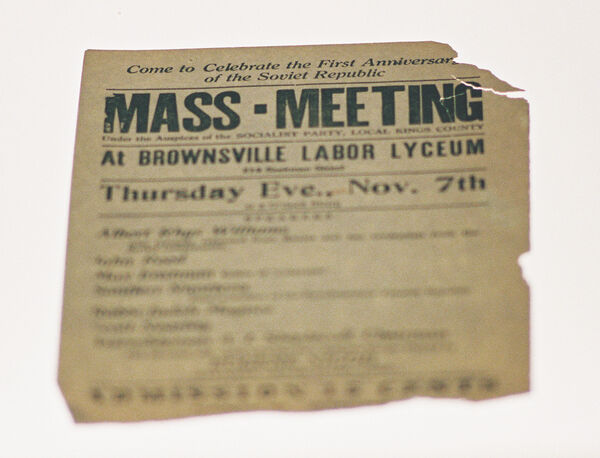

A fragile, disintegrating notice for a “MASS-MEETING” at the Brownsville Labor Lyceum—set in huge block letters spanning the width of the page—lists a lineup including Scott Nearing, John Reed, anti-war writer and poet Max Eastman, well-known Reform rabbi Judah Magnes, and Socialist New York Assemblyman A.I. Shiplacoff. The event, organized by the Kings County Local of the Socialist Party, will open with the playing of the “New Russian Hymn” on a Hardman grand piano. “ADMISSION 15 CENTS” is written in bold at the bottom of the flyer, near the union printer’s mark.

A notice for a mass meeting of the Kings County Socialist Party at the Brownsville Labor Lyceum to celebrate the first anniversary of the Russian Revolution.

Just from reading the handbill, we can feel the excitement of the event, the same excitement nostalgically captured by Ginsberg when he saw Nearing as a boy. There are other announcements of festive events, concerts, and balls. A no-nonsense flyer printed on heavy cardstock that has well withstood the intervening century implores us to “Remember November 14”; to celebrate the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, the Communist Party will host a musical program at an assembly hall on East Second Street. The event will feature an address by the famous socialist feminist writer Rose Pastor Stokes. The Bolshevik suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion is still two years away; the revolution is still full of potential.

Holding individual artifacts like these in our hands, we glimpse the joy of people gathering together to envision a new world. We can trace the connection between the monster rallies and mass meetings in 1919 to anti–Iraq War strategy meetings we each attended at the War Resisters League in 2004 or the occupation of Zuccotti Park in 2011. In accumulation, however, these artifacts become suffocating. Looking back through the detritus of the past century, the Lusk Committee archive stands as a record of an emergent surveillance state. It stands, too, as a heartbreaking monument to the thwarted potential, the naivete and folly of shattered movements.

On our way out of the New York State Archives, still feeling the weight of what we encountered there, we stop on the Cultural Education Building’s fourth floor, which houses an antique carousel. The ride was built in the early 1910s, and would have been shiny and new in 1919. It spun in circles at an upstate amusement park until the ’70s. We admire the hand-carved animals. A few donkeys and deer are scattered among the brightly painted horses.

The century-old carousel calls to mind a scene from Delmore Schwartz’s 1937 short story, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities.” The story’s narrator dreams that he is watching his immigrant parents’ 1909 Brooklyn courtship on a movie screen. The couple travels down to Coney Island and rides on a carousel, just like the one now parked in Albany. “For a moment,” Schwartz writes, “it seems that they will never get off the merry-go-round because it will never stop.” Soon after, the couple quarrels at a fortune teller’s booth on the boardwalk. The narrator, filled with “terrible fear,” shouts at the screen in a vain attempt to change a story that has already concluded, painfully, years ago.

Ben Nadler is the author of The Sea Beach Line: A Novel and Punk in NYC’s Lower East Side, 1981 – 1991. He teaches developmental English at Bronx Community College.

Oksana Mironova is a USSR-born, Brooklyn-raised researcher. She writes about cities and housing.