This is an excerpt from the novel kaddish.com (Knopf, March 2019).

To read an interview with Nathan Englander about the novel, click here.

MIRRORS COVERED and front door ajar, collar torn and sporting a shadow of beard, Larry leans against the granite top of his sister’s fancy kitchen island. He says, “Everyone’s staring at me. All of your friends.”

“That’s what people do,” Dina tells him. “They come, they say kind things, they feel uncomfortable, and they stare.”

It’s only hours after the funeral and, honestly, Larry hates himself for bringing it up. He really thought nothing could add to the despair of his father’s loss. But this, this quiet, muttering stream of well-wishers has made it, for Larry, all the worse.

What he’s taking issue with is the look that he’s getting. It’s not the usual pained nod one naturally offers. Larry’s convinced there’s a bite to it—condemning.

He doesn’t know how he’ll survive a week trapped in his sister’s home, in his sister’s community, when every time one of the visitors glances over, Larry feels himself appraised.

And so he keeps raising his hand to the top of his head, checking for the yarmulke, sitting there like a hubcap for all its emotional weight. Its absence at his own father’s shivah would be the same as standing naked before them.

Sneaked off into the kitchen with his sister, their first moment alone, Larry unloads his complaints in a hiss.

“Tell them,” he says, “to stop looking my way.”

“At a condolence call? You want them not to look at the—” Dina pauses. “What are we, the condoled? The aggrieved?”

“We are the grievances.”

“The mourners!” she says. “You want them not to show that they care?”

“I want them not to judge me just because I left their stupid world.”

Dina laughs, her first since they put their father into the ground.

“This is so like you,” his sister tells him. “To make it negative, to complicate what can’t be any more simple. This bitterness in the face of what is pure niceness is on you.”

“On me? Are you kidding? Are you really saying that—today?”

“You know that I am, little brother. I love you, Larry, but if you choose, even, yes, today, to throw one of your fits—”

“My fits!”

“Don’t yell, Larry. People can hear.”

“Fuck the people.”

“Oh, that’s nice.”

“I mean it,” Larry says, thinking that “fit” may not be a completely inappropriate word.

“Go on then. Curse at the terrible people who will cook for us, and feed us, and drive carpool for me all week, and make sure that we don’t mourn alone. Yes, curse at the nice men who washed our father’s body and prepared the shroud, and laid the shards atop his eyes, and now come to make a minyan in this house.”

“Spare me, Dina. It’s my mourning too, and I should get to feel at home, in your home, as much as them.”

“Who’s saying different? But you have to understand, they aren’t used to it, Larry. Used to what you do.” Dina takes a breath, reorganizing her thoughts. “Memphis Jews are even more conservative than the ones we grew up with. In Brooklyn, even the edgeless have an edge. Here, if you’re going to be radical, people may, a little bit, stare.”

Larry is now the one staring. He stands before his older sister, giving her the best of his blank looks. About what he was doing that anyone could think radical, Larry has no clue.

“Tell me you don’t know,” she says. “Honestly, tell me it’s not on purpose. That you’ve actually forgotten so much.”

“Honestly, honestly, I don’t. I”—and here Larry was going to swear, which Orthodox Jews are forbidden to do. In deference not so much to his sister, but to the opportunity to prove his innocence (that he is not as odd a duck as they think him, that he isn’t doing anything anyone could consider wrong), Larry rights his sentence and, with a stutter, ends it on the word “promise”—“I promise,” he says.

“You really need me to tell you?”

“I do.”

Dina rolls her eyes as she has since Larry was old enough to understand what it meant, and likely before. She explains what she’s sure he knows and is—without a doubt—doing on purpose.

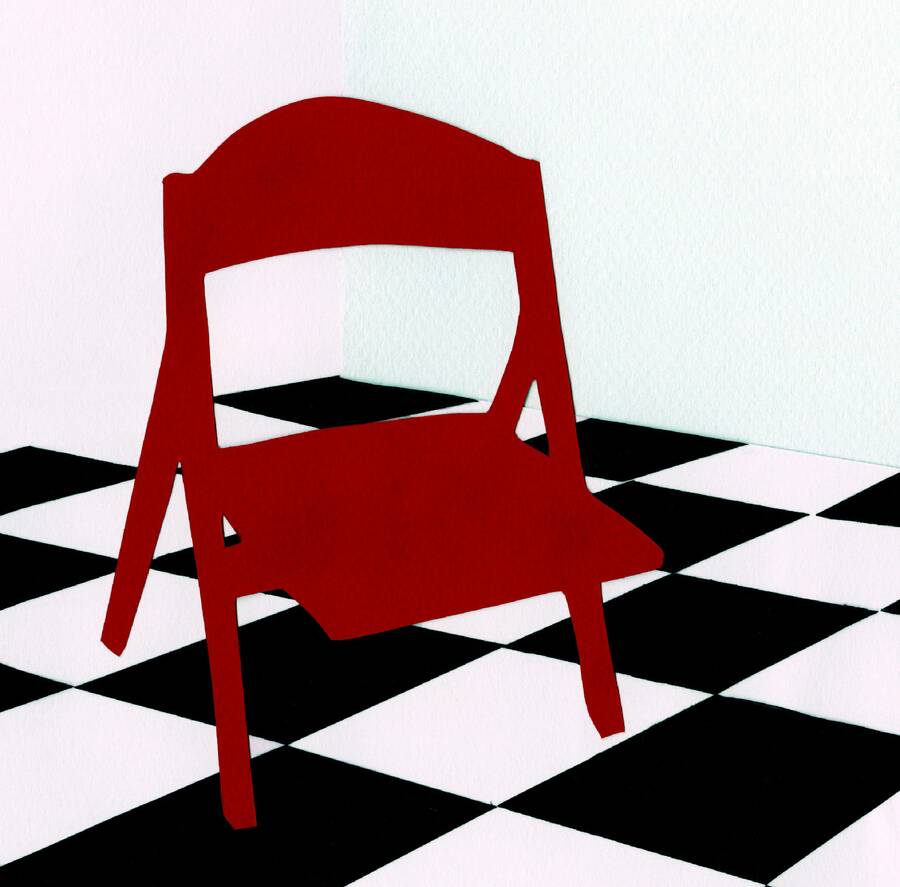

“You step out into the yard. You read a book,” she says, with true sisterly fury. “You sit, like it’s nothing, on a regular chair.”

Larry straightens up at that, pushing with his hands against the counter, stepping back into the radius of his offense.

He gives himself a moment, letting the blood flow to his cheeks, his face reddening, as if, like a chameleon, he can change color at will.

“It’s no reason to treat me like a freak,” he says. “They’re just stupid rules.”

But even as he says it, rebellious little brother that he is, black sheep, and, yes, apostate, Larry understands that for Dina, they’re much more than that. For him to step out of the house. To read a page for pleasure. And, above all, to reject that special shivah perch—the low chair, the wooden box, a couch with the cushions removed. It is too much. That ancient pose, the mourner sitting slope shouldered, ashen faced, and close to the ground, it represents for Dina pure sorrow.

“A stupid chair isn’t what makes it mourning,” Larry says, doubling down. Though he knows, for his sister, a chair absolutely did.

Nathan Englander is the author of the novels kaddish.com, Dinner at the Center of the Earth and The Ministry of Special Cases, and the story collections For the Relief of Unbearable Urges andWhat We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank.