Jews with Money

Last year, a number of American Jewish novels tackled the fraught subject of Jewishness and wealth.

Professor and literary critic Josh Lambert serves as a judge for two major prizes for American Jewish literature, meaning he reads as many new American novels by and about Jews as possible each year. In this annual column for Jewish Currents, he reflects on some of the previous year’s most compelling works of fiction that might be considered “Jewish” in one way or another, and what patterns emerged in this reading.

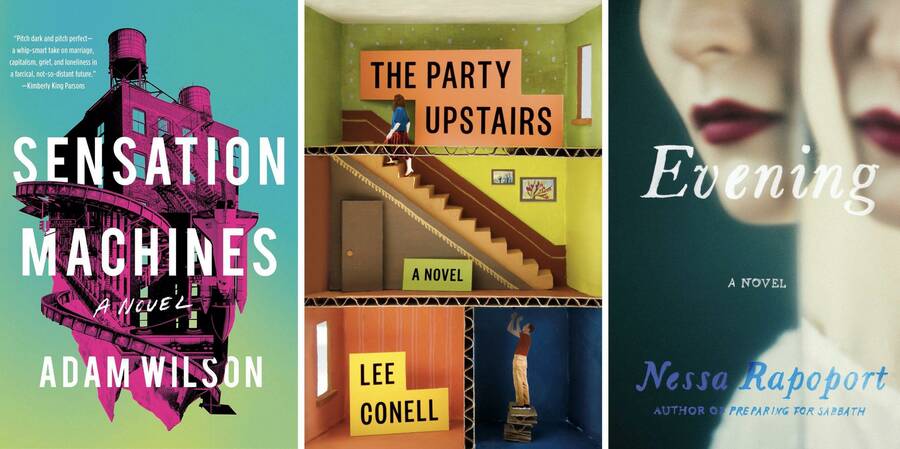

ADAM WILSON’S RECENT NOVEL Sensation Machines takes place in a near-future America much like ours, only a little more so. Congress is debating whether or not to pass a universal basic income policy while a social media guru introduces a newly invasive platform with the disquieting hashtag #WorkWillSetYouFree. Meanwhile, someone gets murdered when a Great Gatsby-themed bankers’ party collides with an Occupy Wall Street “Funeral for Capitalism.” But the book is not only a searing satire of our dystopian economic present; it’s also an exploration of the famously fraught subject of Jews and money. The long history of economic antisemitism means that any discussion of the topic has a wildly overdetermined and uncomfortable quality, so it can be difficult to know what to say about it. Still, a remarkable number of works of fiction published in the past year have given it a shot.

Wilson’s novel—his second, after the National Jewish Book Award-winning Flatscreen—follows Michael Mixner, a flailing Jewish finance bro whose dream is to write a book about Eminem, and his wife Wendy, a once-idealistic writer on an upward trajectory in whatever you want to call the slime that’s left when the residue of advertising, marketing, and journalism pool together. Wendy, who grew up with money, admits that like “most beneficiaries of a bat mitzvah savings account,” she has “a complex relationship with wealth”—though she also notes that if “there’s one thing Manhattan private schools are good for, it’s reminding the children of New Money Jews that, in the grand scheme of savings and loans, they’re relatively deprived.” Michael, meanwhile, grew up lower-middle-class in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and remembers being called “a white-trash kike” in fourth grade before an Ivy League stint and Wall Street career transformed him into a “hipster millionaire.” As their marriage crashes, Michael and Wendy wind up on opposite sides of a national politico-economic cataclysm. Without blaming these (or other) Jews for the rapacious capitalism that is almost certainly going to ruin everything, the novel manages to extract dark comedy out of its recognition that plenty of Jews will likely be involved when it all goes to hell.

Emma Wolf’s Heirs of Yesterday—originally published in 1900 and reissued last fall, thanks to the work of the scholars Lori Harrison-Kahan and Barbara Cantalupo—reminds us that American Jews have had “a complex relationship with wealth” for quite some time. The book’s protagonist, Philip May, is a rich, charismatic Harvard graduate and doctor who’s attracted to Jean Willard, a “beautiful girl” and talented singer. But Jean is well-known as a Jewess, if not a fanatic (“her religion had always lain lightly upon her”), while Philip has been passing as a gentile; he has to decide whether he’s willing to return to his roots to be with her. The novel covers a lot of ground—the French-speaking, Alsatian Jewish community; turn-of-the-century Jewish and non-Jewish social clubs and their admissions policies; Reform theology; the Spanish–American War—but its plot centers on a simple and still active question: Once he has become rich, is there really any reason for a handsome, charming American like Philip to remain Jewish?

In suggesting that wealth itself might threaten the continuing salience of Jewish practices and communities, Wolf’s novel resonates with recent work by the historians Rachel Kranson and Lila Corwin-Berman, who have shown how the growing affluence of American Jews, especially in the postwar decades, often seemed to undermine Jewish traditions and institutions. One Illinois synagogue, Kranson shows, canceled its bar mitzvah program entirely in 1959, out of disgust at the way those ceremonies had been overtaken by “ostentatious displays of wealth and bad taste.”

While some contemporary Jewish novelists, like Wilson, are interested in exploring that tension, many others deal with Jewish wealth by simply taking its existence for granted. Jewish one-percenters can provide punchlines for agreeable social satire, as in David Leavitt’s Shelter in Place, in which wealthy Manhattanites argue about where and how to flee from Trumpism, while joking about the alternatives (“Roses are red, violets are blue, I just voted for a Socialist Jew,” one quips). Elsewhere, Jewish excess is deployed in service of teen drama: In David Hopen’s annoyingly earnest The Orchard, the protagonist, an emigrant from downwardly mobile frum Brooklyn, goes from mooning over wealthy suburbanites’ stuff in a Floridian Modern Orthodox enclave to regarding his Princeton acceptance as a heroic achievement, seemingly without irony on the part of either the character or the author.

Inequality figures a little more prominently, but still uncritically, in Nessa Rapoport’s gentle, pensive novel Evening, which focuses on the fraught cathexis between two Torontonian sisters from a family that, as one of them puts it, was “never rich but earned a stature that felt like wealth.” The protagonist, Eve—a struggling academic who researches forgotten 20th-century women writers and teaches in a continuing education program—is told by her terminally ill sister Tam that she has been “squandering” her life because she doesn’t “even teach serious students who are going for degrees.” Her condescending dig hits home; Eve does feel like a bit of a loser compared to Tam, a successful news anchor, and to the sisters’ imperiously impressive grandmother (who is “not quite” Rapoport’s, the first woman and Jew to receive a doctorate in physics in Canada, and a beloved broadcaster). Tellingly, the novel barely gives us a glimpse of Eve’s working-class students, as if they really don’t matter, at least compared to the question of whether Eve will live up to her family’s aristocratic standards or finally reject them.

OF COURSE, not all American Jews are rich. The most important Jewish novel published this past year, as far as I’m concerned—and the winner of this year’s Edward Lewis Wallant Award—explores how economic inequality plays out among contemporary Jews: Lee Conell’s debut novel, The Party Upstairs, an excerpt of which appeared in this magazine.

The Party Upstairs describes, better than any other novel I can think of, the recent transformation of Manhattan’s Upper West Side, which in the span of a few decades has gone from a place where marginally employed weirdos could plausibly live (remember Seinfeld?) to a neighborhood where the average tenant is a corporate lawyer or hedge fund manager. Aside from a few old-timers holding on to their rent-controlled apartments, the only non-wealthy people on the contemporary UWS are part of the service class, and two of them are Conell’s protagonists: Martin, the live-in superintendent of a co-op, and his 24-year-old daughter Ruby, who grew up in the building’s basement.

Conell’s characters find themselves believing that their Jewishness allows them to traverse class boundaries. While the Latino porter and immigrant construction workers (“one crew Jamaican, one Mexican, one Romanian”) who pass through the building remain firmly and ineluctably separated from the wealthy tenants, Ruby and her dad sometimes seem to cross over. As a child, Ruby had playdates with Caroline, who lived upstairs; they played “Holocaust-orphans-sisters-survivors” together. Martin, himself the offspring of “vaguely traumatized Eastern European ancestors,” gets to know one of the tenants better after trying “a free evening meditation class at the neighborhood JCC.” With these details, Conell signals how memorialization of the Holocaust, and institutions like the Marlene Meyerson JCC Manhattan, attempt to create universalizing links between rich and middle-class or poor Jews. (We might call that attempt “Jewish peoplehood.”)

But in our era of crushing inequality, class divisions aren’t so easy to shrug off, and the drama of the novel inheres in Ruby’s growing recognition that despite every good reason she has to feel that she and Caroline are equals—aside from both being Jewish girls who grew up in the same building, they’re both aspiring artists—she’s actually consigned, permanently, to a lower caste. Over the course of one very bad and hilarious day, the novel follows Ruby’s—and Martin’s—increasingly loopy attempts to reject that conclusion and stave off their immiseration at the hands of condescending, cluelessly privileged tenants and neighbors.

Like many works of modern Jewish literature that draw inspiration from their authors’ leftist commitments, from I.L. Peretz’s “Bontshe the Silent” to Mike Gold’s Jews Without Money to Grace Paley’s stories, Conell’s novel calls attention to the way that economic inequality divides Jews from one another. But The Party Upstairs also self-reflexively highlights how wealth and privilege shape the production of contemporary Jewish art: Some of the novel’s cringiest scenes feature Ruby’s wealthier contemporaries talking earnestly about their artistic practices, and show them exploiting every ounce of their inherited capital to advance themselves.

The novel thus rejects the false myths of meritocracy that American Jews have often leaned on to explain both individual Jewish successes in the arts and other industries as well as, more broadly, American Jews’ upward mobility in the 20th century. It reminds us that most of the contemporary Jewish art we consume has been created by the rich (and certainly not because they’re better artists). It asks us to consider what effects inequality has had on whose stories we have, and haven’t, been hearing.

Josh Lambert is the Sophia Moses Robison Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and English, and Director of the Jewish Studies Program, at Wellesley College.